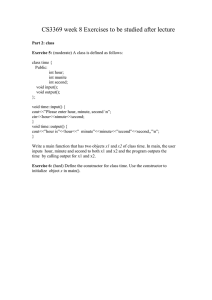

C++ Day 2 (Part 2): References File I/O Tom Latham

advertisement

C++ Day 2 (Part 2):

References

File I/O

Tom Latham

Function arguments

• We saw this morning that functions receive copies of the arguments

passed to them. This is referred to as ‘passing by value’.

• For many cases this is fine. However, there are two scenarios where

this causes problems:

• The function cannot change the value of the argument in such a way

that it is also changed in the calling scope.

• If the object being passed to the function is complicated or large, e.g.

a big vector or a long string there can be considerable overhead

from making the copy, both in terms of time and memory.

• In these cases it would be better if a function could act on the original

object.

References

• References are essentially a means of

creating a new variable for an existing

object.

• Here the new variables are ‘a’ and ‘b’.

• When the swap function is called they are

assigned the objects currently referred to by

the variables ‘x’ and ‘y’.

• The ampersand symbol (&) declares that

‘a’ and ‘b’ are references.

#include <iostream>

void swap( double& a, double& b )

{

double tmp {b};

b = a;

a = tmp;

}

int main()

{

double x {42.3};

double y {11.2};

std::cout << x << "\t" << y << "\n";

• This then allows functions to act on the

actual objects passed to them rather

than copies of them. This is referred to

as ‘passing by reference’.

swap(x,y);

std::cout << x << "\t" << y << "\n";

}

References

• References are essentially a means of

creating a new variable for an existing

object.

• Here the new variables are ‘a’ and ‘b’.

• When the swap function is called they are

assigned the objects currently referred to by

the variables ‘x’ and ‘y’.

• The ampersand symbol (&) declares that

‘a’ and ‘b’ are references.

#include <iostream>

void swap( double& a, double& b )

{

double tmp {b};

b = a;

a = tmp;

}

int main()

{

double x {42.3};

double y {11.2};

std::cout << x << "\t" << y << "\n";

• This then allows functions to act on the

actual objects passed to them rather

than copies of them. This is referred to

as ‘passing by reference’.

swap(x,y);

std::cout << x << "\t" << y << "\n";

}

References

• References are essentially a means of

creating a new variable for an existing

object.

• Here the new variables are ‘a’ and ‘b’.

• When the swap function is called they are

assigned the objects currently referred to by

the variables ‘x’ and ‘y’.

• The ampersand symbol (&) declares that

‘a’ and ‘b’ are references.

#include <iostream>

void swap( double& a, double& b )

{

double tmp {b};

b = a;

a = tmp;

}

int main()

{

double x {42.3};

double y {11.2};

std::cout << x << "\t" << y << "\n";

• This then allows functions to act on the

actual objects passed to them rather

than copies of them. This is referred to

as ‘passing by reference’.

swap(x,y);

std::cout << x << "\t" << y << "\n";

}

Const references

• The only problem is that you

might not want to change the

object being passed but you still

want to use pass by reference

because it is large

• Thankfully there is a way to

ensure (compiler enforced) that

the argument is not changed, by

using a reference to a const

object, often termed a ‘const

reference’

#include <iostream>

void swap( double& a, double& b )

{

double tmp {b};

b = a;

a = tmp;

}

void print( const double& a,

const double& b )

{

std::cout << a << "\t" << b << "\n";

}

int main()

{

double x {42.3};

double y {11.2};

}

print(x,y);

swap(x,y);

print (x,y);

Rule of thumb for function arguments

• If the argument is a built-in type

you can use pass by value

double square( const double x );

• You’ll most likely want to use const

here – it is surprisingly rare that you

actually want to change the value of

the arguments and it is good to

enforce the lack of change to avoid

silly mistakes

• For everything else use const

references

• Unless you need to change the

object, in which case drop the

const

void printString( const std::string& s );

void toLowerCase( std::string& s );

Returning references

• Should large objects also be returned by reference?

• This is a bit trickier since you have to think about the lifetime of

the object being returned.

• If it is local to the returning function, the answer is definitely no.

• It will be destroyed as soon as the function returns, so you’ll

be returning a reference to something that no longer exists!

• At the moment this is the only kind of object lifetime you’ve seen.

We will see other cases in future weeks that mean that return by

reference is viable and even desirable. But you always need to

think carefully about it!

Exercise on function arguments

1. Check whether your existing code is using the most

appropriate form for your function arguments

2. Follow the rule of thumb to choose whether to pass

by value or by reference and make sure everything is

const-correct

3. You can now also package the parsing of the

command-line arguments into a function, which you

should call "processCommandLine"

• Again follow the rule of thumb to choose the best

forms for the function arguments

Input/Output streams

• We’ve so far seen that we can use the cout and cin

objects to print output to the screen and to read input

from the keyboard

• These are examples of I/O streams (hence the name of

the iostream header!)

• We’d like to be able to use these to read from and write

to files as well (helps to avoid a lot of typing!)

• Can use the types provided in the fstream header file

Output file streams

• To use an output file stream you must:

• Include the appropriate header file:

#include <fstream>

• Instantiate an instance of an ofstream type:

std::string name {"myoutputfile.txt"};

std::ofstream out_file {name};

• Unlike with std::cout, you need to check that the file was correctly opened

before you can write to it:

bool ok_to_write = out_file.good();

• Then you can use that instance exactly as you would use std::cout

out_file << "Some text\n";

Input file streams

• To use an input file stream you must:

• Again include the appropriate header file:

#include <fstream>

• Instantiate an instance of an ifstream type:

std::string name {"myinputfile.txt"};

std::ifstream in_file {name};

• Again, you need to check that the file was correctly opened before you can read from it:

bool ok_to_read = in_file.good();

• Then you can use that instance exactly as you would use std::cin

char inputChar {'x'};

in_file >> inputChar;

Closing files (and opening new ones)

• With both input and output files you can do:

file.close();

• This closes the file and any further attempts to read or write will fail

• It is done automatically when a file stream object is destroyed (e.g. when it goes out of scope), so

you don’t always need to do this explicitly

• However, you do need to do this first if you want to then use the same file stream object to open

another file (although the circumstances under which you would want to do this are rare – it is clearer

to use a separate object for each file):

file.open("myfirstfile.txt");

...

file.close();

file.open("myotherfile.txt");

...

Appending rather than overwriting

• By default when you open an output file stream and the file

already exists, it will overwrite the contents of the file

• However, it is possible to open an output file stream in a

mode where whatever you write to it will instead be

appended to the file:

std::ofstream out_file( name, std::ios::app );

• For more details on this see, for example:

http://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/io/ios_base/openmode

Exercise on file I/O

• Now we have the knowledge necessary to implement

reading the input text from file rather than the keyboard and

to write the cipher text to a file rather than the screen

• You already have command line options that provide the

names of these files

1. Implement the new code to do these operations if the

corresponding option is specified on the command line (if

the option is not specified, the program should continue to

read from the keyboard and/or write to screen as

appropriate)

Function overloading

• Let’s look again at the swap function

that we saw earlier on and which

swaps the values of two double’s

• We could equally want to write a

function that swaps the values of

two integers and indeed we can do

exactly that

• So we have two functions with the

same name (since they have the

same functionality) but different

arguments – this is referred to as

overloading – and is perfectly valid

code

void swap( double& a, double& b )

{

double tmp {b};

b = a;

a = tmp;

}

void swap( int& a, int& b )

{

int tmp {b};

b = a;

a = tmp;

}

Templated functions

• In this particular case, we can see

that the only difference between

the two swap functions is the

types of the arguments and the

tmp variable

• We are duplicating code – and

you can see that this would

proliferate if we wanted to have

other functions to swap two

float’s or two bool’s

• This duplication can be eliminated

using templates

void swap( double& a, double& b )

{

double tmp {b};

b = a;

a = tmp;

}

void swap( int& a, int& b )

{

int tmp {b};

b = a;

a = tmp;

}

Generic programming

• This function template definition specifies a

family of functions that swap the values of

two variables

• The type of these variables is specified by

the template parameter T

• The function can be used with any type that

provides the operations performed

• In this case the operations are copyconstruction and assignment

• In this particular case, the compiler can

deduce the template parameter from the

type of the arguments

template <typename T>

void swap( T& a, T& b )

{

T tmp {b};

b = a;

a = tmp;

}

int main()

{

double x {42.3};

double y {11.2};

swap(x,y);

• In some scenarios that isn’t possible, and

so it has to be specified explicitly:

int i {4};

int j {-6};

swap<double>(x,y);

• This can also be done even when the compiler

can deduce the type, e.g. to provide clarity

}

swap(i,j);

Generic programming and static polymorphism

• Note that we’ve already encountered the template syntax when using the vector

container this morning

• We’ll see more examples of generic programming on Day 4 when we look in

more detail at the so-called Standard Template Library (STL), in particular the

generic algorithms

• Another term that you will hear in connection with templates is “static

polymorphism”

• Polymorphism means that a single entity (in the example we just looked at, a

function) has the ability to be used with many different types

• Static refers to the fact that the type selection is locked-in at compile time

(we’ll encounter run-time type selection or dynamic polymorphism on Day 5)

Exercise on template functions

• You'll have seen that your reading operation is

extremely similar whether you're using the file or the

keyboard

1. Turn the corresponding functions into a templated

function, which you should call "readStream"

2. Consider whether it is worth doing the same for the

output functions

The Caesar Cipher

• Finally, we’re ready to implement our first cipher

• A substitution cipher - each letter in the input text is

replaced by another according to a constant rule

• Named after Julius Caesar - the first recorded user of

this cipher!

Caesar Cipher Encryption Substitution Rule

• Replace each letter in Plaintext string by that K letters

rightward in the Alphabet.

• If the shift goes beyond the end of the Alphabet, wrap

around to ‘A’ and continue counting rightwards.

• Shift K is an integer [0,25] and is the Key for the cipher

Encrypting With the Caesar Cipher, K=5

Plaintext

HELLOWORLD

K=5

K=5

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

Ciphertext

MJQQT

Encrypting With the Caesar Cipher, K=5

Plaintext

HELLOWORLD

K=5

K=5

Wrap

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

Ciphertext

MJQQTBTWQI

Caesar Cipher Decryption Substitution Rule

• Replace each letter in CipherText by that K letters

leftward in the Alphabet.

• If the shift goes beyond the start of the Alphabet, wrap

around to ‘Z’ and continue counting leftwards.

• Shift K is an integer [0,25] and is the Key for the cipher

Decrypting With the Caesar Cipher, K=5

Ciphertext

Wrap

MJQQTBTWQI

K=5

K=5

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

Plaintext

HELLOWORLD

C++ Implementation Hints

• Many ways to implement the Caesar Cipher in C++

• We're going to create a function called CaesarCipher

• Think about what the interface should be (input and

outputs) and the “things” involved (like the Alphabet)

• To handle the “wraparound”, the Modulus operator %

could be useful

• Think about how to test that your Ciphertext is correct

Exercise implementing the Caesar Cipher

1. Implement the Caesar Cipher (using the hints above)

• Will need other cmd-line arguments to be added for

the encrypt/decrypt flag and to provide the key

2. When you have finished, commit and tag your

respository (and push to github), and email us a link

to the tag