UPDATE Anti-Money Laundering

advertisement

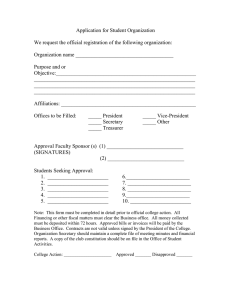

UPDATE Anti-Money Laundering JANUARY 2002 The International Money Laundering Abatement and Anti-Terrorist Financing Act of 2001: What it Means for Broker-Dealers, Investment Companies, Banks and Other Financial Institutions Federal regulators are quickly responding to the short deadlines imposed in the International Money Laundering Abatement and Anti-Terrorist Financing Act of 2001 (the Act), enacted as part of the USA PATRIOT Act, on October 26, 2001. On December 20, 2001, the Department of the Treasury (Treasury) issued proposed regulations intended to clarify application of the new recordkeeping requirements and shell bank prohibitions in the Act to brokerdealers, banks and other financial institutions, and to require broker-dealers to report suspicious transactions. An interim rule also issued by Treasury on December 20, 2001 requires trades and businesses to report cash transactions of more than $10,000. Contents Adopted in response to terrorist attacks in order to strike at the source of terrorist funding, the Act sets broad parameters and ambitious goals for financial institutions to identify and prevent, in the first instance, possible money laundering activity. Similar to the privacy provisions of Gramm-Leach-Bliley, the Act will affect the operations of virtually every financial institution and also require coordination among various federal agencies for implementation. Although banks and banking regulators have been attuned to money laundering problems for many years, non-bank financial institutions and their regulators have had a far more limited involvement. Broker-Dealer SAR Reporting ..................................... 10 Primary Money Laundering Concerns ....................... 11 Summary ........................................................................... 2 Coverage of the Act ......................................................... 2 Deadlines .......................................................................... 3 Agency Review and Reports; Possible Future Legislation .................................... 4 Penalties for Non-Compliance; Expanded Immunity for SAR Reporting .......................................... 13 Balancing National Security v. Privacy ........................... 13 Information Sharing .................................................... 13 Government Surveillance ............................................ 13 Federal Regulators ........................................................... 5 Privacy Concerns .......................................................... 14 Obligations of “Covered Financial Institutions” ........... 5 ................................................................................................ Foreign Shell Banks ...................................................... 5 This Update was produced by K&L’s multi-office, interdisciplinary anti-money laundering practice, which provides enterprise-wide solutions for financial institutions to help them understand and comply with newly enacted money-laundering legislation. We invite you to visit our website at www.kl.com, or to contact a member of our practice (see last page of this Update) if you have any questions, would like more information about our services, or if we can provide you with copies of the legislation. This Update was prepared by Diane E. Ambler (dambler@kl.com), James E. Day (jday@kl.com), and Kathy Kresch Ingber (kingber@kl.com). Obligations of “Financial Institutions” .......................... 6 Anti-Money Laundering Programs ............................ 6 Due Diligence Programs .............................................. 8 Private Banking Accounts ....................................... 8 Correspondent Accounts ........................................ 8 “Know Your Customer” Procedures ........................... 9 The Act laid down a number of substantive requirements. Firms that fail to follow these requirements could face substantial exposure; the Act imposes severe civil and criminal penalties for violations. Part IX identifies conflicting national security and privacy concerns. suggests guidelines for compliance. Part VII identifies the substantive obligations of financial institutions and suggests guidelines for compliance. Part VIII highlights penalties for non-compliance with the provisions of the Act. Part IX identifies conflicting national security and privacy concerns. I. II. COVERAGE OF THE ACT SUMMARY The purpose of this K&L Update is to discuss the principal provisions of the Act in detail and, more importantly, to highlight the practical impact of the new provisions on the compliance functions and operations of the financial institutions affected by the Act. In addition, it identifies general guidelines for compliance. For the time being, financial institutionsparticularly non-bank financial institutionsmay be able to do little more than assess their business relationships, establish internal chains of authority and responsibility, and begin the process of identifying and educating affected personnel. Since more than one member of an entitys corporate family may be covered by the Act, financial services firms will need to review the policies and procedures of their various subsidiaries to develop uniformity and consistency. Throughout this K&L Update, a number of themes that resound in the early wake of the Acts enactment will be highlighted n n n How are financial institutionsparticularly nonbank financial institutionsaffected? What important deadlines are looming and what should financial institutions be doing right now? What federal regulators are responsible for implementation of the Act and how will jurisdictional issues work? Part II of this Update identifies the various financial institutions covered by the Act and briefly describes the Acts impact on each. Part III sets forth the deadlines established by the Act by which regulators and financial institutions must take certain actions. Part IV notes the requirements for agency review and reports, as experience with the provisions of the Act develops. Part V describes the jurisdiction of federal regulators. Part VI identifies the substantive obligations of covered financial institutions and 2 Congress intended the Act to sweep broadly. Congress therefore deliberately chose to have the anti-money laundering provisions of the Act apply not just to banks, but also to financial institutions, as defined in the Bank Secrecy Act and further supplemented by the Act. Financial institutions, as defined in the Bank Secrecy Act, include, among other things, banks, trust companies, thrift institutions, private bankers, US agencies or branches of foreign banks, investment bankers, broker-dealers in securities or commodities, investment companies, and insurance companies. 1 The Act enlarges the definition of financial institutions to include futures commission merchants, commodity trading advisors, and commodity pool operators. Certain of these financial institutions, specifically, banks, thrifts, trust companies, credit unions, US branches or agencies of foreign banks, and registered broker-dealers, are further designated as covered financial institutions subject to particular requirements in the Act related to correspondent accounts with foreign banks. Banks. Banks have been dealing with extensive antimoney laundering laws and regulations since the passage of the Bank Secrecy Act in 1970. Even so, the Act increases their recordkeeping, monitoring and reporting obligations. Accordingly, even banks with up-to-date anti-money laundering procedures will have to substantially revise those procedures in light of the new Act. Broker-Dealers. The additional burden of the new Act on broker-dealers and other non-bank financial institutions is likely to be greater than on banks. For example, the Act provides that mandatory reporting of suspicious activities shall be extended to brokerdealers.2 Under current regulations, only banks, subsidiaries of bank holding companies (such as bank broker-dealers), casinos, and money services businesses have been required to file SARs. The Act KIRKPATRICK & LOCKHART LLP ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING UPDATE substantially expands this universe, and the Secretary of the Treasury (Secretary) has just issued proposed regulations extending mandatory SAR reporting to all broker-dealers registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) (including insurance companies or their affiliates that are registered broker-dealers solely for the purpose of selling variable annuity contracts). Thus, to the extent that broker-dealers have not yet developed anti-money laundering policies and procedures to identify and report suspicious activities, they will be expected to do so. In addition, proposed regulations just issued by Treasury specifically apply the Acts shell bank restrictions to broker-dealers maintaining correspondent accounts with foreign banks. Treasury has listed examples of such accounts to include prime brokerage accounts, foreign currency accounts, futures accounts, trading accounts and custody accounts. Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) Regulated Entities. The Act permits the Secretary, in consultation with the CFTC, to require entities it regulates, such as futures commission merchants, commodity trading advisors, and commodity pool operators, to file SARs. Insurance Companies. Insurance companies are financial institutions, but not covered financial institutions, under the Act. There are no provisions in the Act specifically targeting insurance companies or their activities, although the Act does reference a [s]tate financial institutions supervisory agency, which would appear to include state insurance regulators, as an appropriate recipient of reports prepared by the Secretary pursuant to the requirements of the Act. In addition, the Secretary indicated it would remove an interpretive exemption from SAR reporting for insurance companies or their affiliates that are registered broker-dealers solely for the purpose of selling variable annuity contracts. Investment Advisers. Notably absent from the definitions of financial institution or covered financial institution under the Act are investment advisers. Therefore, with one exception, the new mandates in the Act do not appear to apply directly to investment advisers. The Act does require the Secretary to issue regulations, by April 2002, JANUARY 2002 requiring entities not included in the term financial institution, which could include investment advisers, to file CTRs with Treasury. Interim regulations issued by Treasury on December 20, 2001 apply only to persons engaged in a trade or business. Investment Companies. Investment companies are financial institutions, but not covered financial institutions, under the Act. Although certain of the Acts provisions thereby apply to investment companies, it is not clear necessarily how. In that vein, the Act mandates the Secretary, the SEC and the Federal Reserve Board (the Fed) to jointly submit a report to Congress on recommendations, by October 26, 2002, for effective regulations to apply the various provisions of the Bank Secrecy Act to investment companies, including private investment companies falling within Section 3(c)(1) or Section 3(c)(7) of the Investment Company Act of 1940. III. DEADLINES The Act establishes an aggressive compliance schedule for financial institutions and federal regulators. n By December 25, 2001 Covered financial institutions will be prohibited from opening or maintaining correspondent accounts with foreign shell banks. Covered financial institutions that maintain correspondent accounts with foreign banks will be required to have records identifying the owners of the foreign bank and providing the name and address of persons authorized to accept service of legal process in the US. n n By December 31, 2001Federal banking regulators, when ruling on an application under the Bank Holding Company Act or the Federal Deposit Insurance Act, must consider the effectiveness of the financial institutions anti-money laundering activities. By January 1, 2002 (issued December 20, 2001)The Secretary, after consultation with the SEC and other federal regulators, is to publish proposed regulations (to be finalized by July 1, 2002) extending mandatory SAR reporting to broker-dealers registered with the SEC. Kirkpatrick & Lockhart LLP 3 n n By February 23, 2002The Secretary is to issue regulations to encourage further cooperation among financial institutions, their regulatory authorities and law enforcement authorities for the sharing of financial information regarding persons suspected of participating in money laundering activities or terrorist acts. Financial institutions will be required to adopt anti-money laundering programs that include policies, procedures, and controls to detect and prevent money laundering, designate a compliance officer to oversee the program, provide for employee training, and provide for regular audits of their anti-money laundering program, subject to regulations to be issued by the Secretary related to the size, location and activities of the financial institutions covered. The Secretary is to issue regulations implementing new CTR reporting requirements. Among other things, these regulations could require persons not included in the term financial institution, such as investment advisers, to file CTRs with Treasury. Interim regulations issued by Treasury on December 20, 2001 require CTR reporting by persons who, in the course of engaging in a trade or business, receive currency in excess of $10,000 in one or more related transactions. 4 n By April 24, 2002 The Secretary, in consultation with the appropriate federal functional regulators, is to issue regulations delineating the due diligence policies, procedures, and controls required for correspondent accounts and private banking accounts for non-US persons. Compliance with these regulations is required by July 23, 2002. n n By July 1, 2002The Secretary, after consultation with the SEC and other federal regulators, is to issue final regulations (to be proposed by January 1, 2002) extending mandatory SAR reporting to broker-dealers registered with the SEC. n By July 23, 2002Financial institutions will be required to adopt detailed due diligence procedures for correspondent accounts and private banking accounts for non-US persons. Implementing Treasury regulations are to be finalized by April 24, 2002. By July 26, 2002The Secretary is to establish a secure network that allows financial institutions to make SAR filings on-line and that makes timely information available to financial institutions. By October 26, 2002 The Secretary is to submit a report to Congress jointly with the SEC and the Fed on recommendations for effective regulations to apply the requirements of the Act to investment companies, including private investment companies. Financial institutions will be required to adopt know your customer procedures for opening customer accounts. In addition, the Secretary is authorized to issue regulations governing maintenance of concentration accounts by financial institutions. The Secretary also now has the power to require financial institutions to monitor and keep records regarding transactions involving particular foreign jurisdictions, financial institutions, transactions and/ or accounts that the Secretary identifies as primary money laundering concerns. There are no deadlines by which the Secretary must issue these regulations. IV. AGENCY REVIEW AND REPORTS; POSSIBLE FUTURE LEGISLATION Not later than April 2002, the Secretary, in consultation with the federal functional regulators, must submit a report to Congress with recommendations for identifying foreign nationals. In addition, the Secretary must also by that date submit a report to Congress relating to the role of the Internal Revenue Service in administering the Bank Secrecy Act, including possible recommendations to transfer functions to other government agencies. KIRKPATRICK & LOCKHART LLP ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING UPDATE Not later than April 2002, and annually thereafter, the Secretary must submit a report to Congress on methods for improving compliance with foreign financial agency transaction reporting requirements. Not later than October 26, 2002, the Secretary must submit a report to Congress on the need for any additional legislation related to domestic or international transfers of money outside of the conventional financial institutions system. By the same date, the Secretary must also submit another report to Congress regarding the effectiveness of the CTR filing requirements, in light of the volume of CTR filings and the failure of some financial institutions to utilize the exemptions available. Not later than April 2004, the Secretary, in consultation with various federal agencies, including the SEC and federal banking agencies, must evaluate the operations of the Act and make recommendations to Congress about possible further legislative action. In any event, the Act is scheduled to sunset after September 30, 2004 upon joint resolution of Congress. Reports prepared pursuant to the requirements of the Act are to be made available to state and federal agencies and organizations in certain circumstances upon request, but they are exempt from general disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act. V. FEDERAL REGULATORS The Act appoints a single federal agency, Treasury, to adopt regulations and oversee compliance with the Acts requirements. In several instances, the Act instructs Treasury to consult and coordinate with other federal functional regulators 3 or specific federal agencies. In other instances, the Act instructs Treasury to adopt joint regulations with specified other agencies. This arrangement intentionally focuses regulation and enforcement in one US agency in order to streamline anti-money laundering efforts tailored to problems presented by foreign jurisdictions, financial institutions and accounts. In order to successfully address the business issues unique to the various financial institutions involved, the Act is structured to require Treasury to work with other appropriate regulators. JANUARY 2002 VI. OBLIGATIONS OF COVERED FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS Foreign Shell Banks; Recordkeeping Substance of the Requirement Effective December 25, 2001, covered financial institutions may not establish, maintain, administer, or manage a correspondent account4 in the US for or on behalf of a foreign bank that does not have a physical presence 5 in any countryknown as a shell bankunless the shell bank is an affiliate of a depository institution, credit union or foreign bank that maintains a physical presence in the United States, or a foreign country and is supervised by a banking authority.6 The Act requires covered financial institutions that maintain any foreign bank correspondent accounts in the US to maintain records identifying: (i) the owners of the foreign bank; and (ii) the name and address of a person residing in the US authorized to accept service of process with regard to the correspondent account. These records must be turned over to a Federal law enforcement officer within 7 days of receipt of a request for them. Under the Act, a covered financial institution must comply with a request of an appropriate Federal banking agency7 for information and account documentation for any account opened, maintained, administered or managed in the United States not later than 120 hours after receipt of the request. The rule applies to all accounts at a covered financial institution and not just accounts of foreign persons or non-citizens. Since any requests for information will be made by the appropriate Federal banking agency and not by law enforcement officials, no court process (i.e., summons, subpoena or courtapproved warrant) appears to be involved. The Act subjects foreign banks that maintain correspondent accounts in the US to subpoena and summons with respect to records, including records maintained outside the US, relating to those accounts. A covered financial institution must terminate any correspondent relationship with a foreign bank not later than 10 business days after receipt of written notice from the Secretary or the Kirkpatrick & Lockhart LLP 5 Attorney General that the foreign bank has failed to comply with a summons or subpoena issued in relation to the correspondent account (unless the foreign bank has initiated court proceedings to contest the summons or subpoena). Proposed Regulations On December 20, 2001, the Secretary issued proposed regulations intended to codify interim guidance, with some modifications, published by Treasury on November 27, 2001 with regard to the shell bank prohibitions and recordkeeping requirements for correspondent accounts maintained by foreign banks. The proposed regulations apply the definition of correspondent account in the Act to all covered financial institutionsincluding brokerdealers. In this regard, Treasury stated that brokerdealers must comply with these provisions of the Act with respect to any account they provide in the US to a foreign bank that permits the foreign bank to engage in securities transactions, funds transfers, or other financial transactions through that account. 8 Foreign bank is defined in the proposed regulations as any organization that: (i) is organized under the laws of a foreign country; (ii) engages in the business of banking; (iii) is recognized as a bank by the bank supervisory or monetary authority of the country of its organization or principal banking operations; and (iv) receives deposits in the regular course of its business. Among other things, it includes a branch of a foreign bank in a US territory but not a US branch or agency of a foreign bank. The term owner is also defined in the regulations and includes certain direct and indirect owners likely to be able to influence the foreign banks operations.9 Also adopted by the proposed regulations are model certifications for account holders to state whether they are, or whether they provide banking services to, a shell bank covered by the prohibition. Use of the model certifications provides covered financial institutions a safe harbor for the obligations under these provisions. Treasury also indicated that a covered financial institution may use relevant information provided by a foreign bank that files an Annual Report on Form FR Y7 with the Fed. The rules propose a requirement that covered financial institutions verify the information provided by a foreign bank every two years or at any time a covered financial institution has reason to believe that the previously provided information is no longer accurate. A model recertification will provide a covered financial institution a safe harbor in connection with the verification of previously provided information. Information requested by a covered financial institution under the proposed rules and received within 90 days after publication of the final rules will be deemed to satisfy the rule requirements until such time as the information must be verified. Guidelines for Compliance Covered financial institutions are required to take reasonable steps to ensure that any correspondent account established, maintained, administered or managed by or for a foreign bank is not, and is not being used indirectly by, a shell bank. At the least, a covered financial institution should consider the relationships it has with foreign banks, review its correspondent accounts with foreign banks, and have its foreign bank account holders complete the model certifications suggested by Treasury. VII. OBLIGATIONS OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS Anti-Money Laundering Programs Substance of the Requirement The Act requires each financial institution including broker-dealers, investment companies and insurance companiesto develop and institute an anti-money laundering program that must, at a minimum: n n n n include internal policies, procedures, and controls; designate a compliance officer to administer and oversee the program; provide for ongoing employee training; and include an independent audit function to test the program. The Secretary is obligated to issue regulations by 6 KIRKPATRICK & LOCKHART LLP ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING UPDATE April 24, 2002, the effective date of this provision, that take into account the size, location, and activities of the financial institutions affected. These regulations may also establish minimum standards for financial institutions anti-money laundering programs. In adopting these regulations, the Secretary must consult with the appropriate federal functional regulator, including the SEC and the CFTC. n n Guidelines for Compliance Treasury has advised that the focus of a brokerdealers anti-money laundering compliance program should be the development of procedures that can reasonably be expected to promote the detection and reporting of suspicious activity. A compliance program that captures only those transactions above a set dollar threshold likely would not be satisfactory. Treasury recognized, however, that compliance programs would necessarily vary to reflect the size and nature of a broker-dealers operations. In developing their expanded anti-money laundering programs, financial institutions may want to keep the following guidelines in mind. Much of the following is derived from SEC staff guidance that predated the Act. While it may be premature to adopt procedures before regulations are introduced this spring, preliminary thought could be given to the types of procedures that may be appropriate, along the lines of the following: Policies and Procedures. Financial institutions should consider the nature and extent of their activities, the types of accounts that they maintain, and the types of transactions in which their customers engage. Procedures could n n Identify suspicious activities that may need to be reported on an SARsuch as an unusual volume of wire transfers, wire transfers to prohibited individuals, or wire transfers or transactions with suspect countriesperhaps through the use of automated systems. Identify customer risk indicators that would trigger additional scrutinysuch as when a customer refuses to identify or indicate a legitimate source for his or her funds and other assets when opening an account. JANUARY 2002 n Ensure that procedures are in place to alert the financial institution when the Secretary identifies a primary money laundering concern and requires heightened due diligence for transactions with such primary money laundering concern. Identify relationships that could be comparable to the Acts coverage of correspondent accounts and private banking accounts and potential areas of risk that raise red flags over any possible unlawful activities in those types of accounts. Address the added due diligence and other provisions in the Act, and ensure that procedures prohibit transactions with individuals, entities, and jurisdictions identified by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), including those individuals on OFACs Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List. Compliance Officer. The financial institution must designate an anti-money laundering compliance officer. Consistent with SEC statements in other compliance areas, the officer should have sufficient responsibility and authority to implement and enforce the financial institutions anti-money laundering policies and procedures. This provides evidence of senior management commitment to antimoney laundering efforts and, more importantly, provides added insurance that the officer will have sufficient clout to investigate potentially suspicious activities. Employee Training. Training must encompass all relevant employees and be constantly reevaluated and updated. Employees should be able to recognize signs of possible money laundering (suspicious activities) and know what to do once a risk is identified. Programs will need frequent reevaluation to ensure that employees are informed about, and understand their obligations under, the new Act and its implementing regulations. Updating training programs will be particularly important as regulations implementing the provisions of the Act are proposed and adopted. Audit. A financial institutions anti-money laundering program must provide for an independent audit to review and test implementation of the financial institutions policies and procedures. Kirkpatrick & Lockhart LLP 7 Financial institutions should ensure that the audit takes place no less frequently than annually and covers all aspects of its operations. Due Diligence Programs The Act imposes substantial new due diligence procedural requirements for every financial institution that establishes, maintains, administers, or manages a private banking account10 or a correspondent account11 in the US for a non-US person. While these provisions appear to be most relevant in the context of banks and banking relationships, the Secretary is required to clarify these provisions as they apply to other, non-bank financial institutions in consultation with the appropriate federal functional regulators.12 Implementing regulations are to be issued by April 24, 2002, and these provisions take effect on July 23, 2002. Private Banking Accounts Substance of the Requirement The due diligence procedures for private banking accounts require the financial institution to take reasonable steps to: n n Ascertain the identity of the nominal and beneficial accountholders and the source of funds deposited into the account; and Conduct enhanced scrutiny of accounts requested or maintained by or on behalf of a senior foreign political figure, or any immediate family member or close associate, to detect and report transactions that may involve the proceeds of foreign corruption. Congress intended that these new due diligence procedures apply not only to private banking accounts physically located in the US, but also to private banking accounts that are physically located outside of the US and managed by US personnel from inside the US. Guidelines for Compliance These procedures may not be novel for banks and other financial institutions that have had to file SARs under current law and have faced heightened 8 scrutiny recently over the use of private banking accounts by foreign public officials. For brokerdealers and other non-bank financial institutions, however, the provisions are likely to be new. Accordingly, broker-dealers and other non-bank financial institutions may want to prepare for the issuance of regulations. They should carefully monitor future pronouncements from the Secretary while also determining the extent to which they offer private accounts, and whether the circumstances surrounding such accounts would trigger the Acts additional due diligence provisions. If so, they should ascertain whether they could collect the information required by the Act, or identify the accounts for which such information is not available. Correspondent Accounts Substance of the Requirement Reflecting the particular concern Congress has expressed over the use of certain correspondent accounts to launder money, the Act requires enhanced due diligence procedures for correspondent accounts requested or maintained by or on behalf of a foreign bank operating: (a) under an off-shore banking license; or (b) under a banking license issued by a foreign country that has been designated either as non-cooperative with international anti-money laundering principles or procedures or by the Secretary as a primary money laundering concern. At a minimum, the Act provides that enhanced due diligence procedures for correspondent accounts will require a financial institution to take reasonable steps to: n n n Ascertain the ownership of the foreign bank; Carefully monitor the account to detect and report any suspicious activity; and Determine whether the foreign bank maintains correspondent accounts for any other bank and, if so, the identity of those banks and related due diligence information. These requirements are not meant to be comprehensive. Congress intended that financial institutions take additional reasonable steps before opening or operating correspondent accounts for KIRKPATRICK & LOCKHART LLP ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING UPDATE foreign banks, including steps to check the foreign banks past record and local reputation, the jurisdictions regulatory environment, the banks major lines of business and client base, and the extent of the foreign banks anti-money laundering program. Guidelines for Compliance A country can be identified as non-cooperative unilaterally by the Secretary or by agreement of the US and other countries through the Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering (FATF). The FATF has currently identified 19 countries as noncooperative.13 Some are obvious choices, but others are not. Moreover, the list changes periodically as the international community, through the FATF, determines that certain additional countries are non-cooperative or others previously identified as non-cooperative mend their ways. Thus, broker-dealers and other financial institutions will need to keep a close eye on the FATF and amend their policies and procedures as the FATF amends its list or the Secretary identifies other countries as non-cooperative. The sweep of these provisions could be quite broad. One country listed as non-cooperative is Hungary. Thus, under the new procedures, listing a country as non-cooperative triggers heightened due diligence for banks operating in that country. Thus, if the account is opened by a bank operating in Hungary, the Act would require the US financial institution to ascertain the ownership of the Hungarian bank and may require it to evaluate the history of the Hungarian bank, its client base, and the adequacy of its money laundering policies and procedures. It will also need to determine whether the Hungarian bank offers correspondent accounts to other banks and perform due diligence on those banks. Know Your Customer Procedures Substance of the Requirement The Act requires the Secretary, jointly with federal functional regulators, to issue implementing regulations by October 26, 2002, imposing mandatory know your customer procedures for financial institutions to follow in opening customer accounts. At a minimum, these procedures will JANUARY 2002 require the financial institution to verify to the extent reasonable and practical the identity of any person seeking to open an account, to maintain records of the information used to verify the persons identity, and to check that the potential customer does not appear on any list of known or suspected terrorists or terrorist organizations. There is a recognition that one size wont fit all: the Act mandates that, in adopting regulations, the Secretary take into consideration the various types of accounts maintained by various types of financial institutions, the various methods of opening accounts, and the various types of identifying information available. Appropriate federal functional regulators may, by rule or order, exempt financial institutions or types of accounts from the requirements of these regulations, in accordance with standards and procedures prescribed by the Secretary. Not later than April 24, 2002 (before issuing final regulations), the Secretary must (in consultation with the federal functional regulators) issue a study to Congress recommending how to require foreign nationals to provide financial institutions the information necessary for the new verification provisions, apply for or obtain an identification number similar to a Social Security or tax identification number, and establish a system for financial institutions to review lists of known or suspected terrorists. Guidelines for Compliance Financial institutions should take advantage of the time provided before these provisions become effective to prepare for them. Financial institutions should analyze the type of information they collect for different kinds of accounts and identify the customers, accounts, or types of accounts for which the information required by the Act will be difficult to verify. For those accounts, the financial institution may want to consider whether it is advisable to maintain the accounts and, if so, devise procedures to obtain the necessary information. Also, the financial institution should ensure that it can easily and frequently access lists of known or suspected terrorists or terrorist organizations principally the list of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons issued by OFAC. Among other Kirkpatrick & Lockhart LLP 9 things, that list designates certain individuals and entities as known or suspected terrorists or terrorist organizations. The list is long, and OFAC has updated it frequently since the September 11 attacks. Moreover, many of the individuals are listed under several names and aliases. The length and complexity of the list make it impractical and inefficient to rely on a manual review of the list each time a customer account is opened. Accordingly, prior to the effective date for this provision, financial institutions may want to explore ways to electronically cross-verify the list each time an account is opened. Broker-Dealer SAR Reporting Substance of the Requirement The Act substantially expands the universe of entities required to file SARs. SARs are filed with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), the agency within Treasury responsible for anti-money laundering activities. Current federal regulations require only banks, subsidiaries of bank holding companies, casinos, and money services businesses to file SARs. Thus, broker-dealers, investment advisers, and investment companies have generally not been required to make such reports, unless they were subsidiaries of bank holding companies. Many broker-dealers have, however, filed SARs voluntarily. The Act expands the reach of this reporting scheme. The Secretary, after consultation with the SEC and the Fed, issued proposed regulations on December 20, 2001, requiring registered brokerdealers to file suspicious activity reports. Final regulations requiring such reporting must be published before July 1, 2002. Under the proposed regulations, the SAR reporting requirements for broker-dealers will be effective 180 days after final regulations are published in the Federal Register. These proposed regulations require broker-dealers to file SARs in certain situations and permit additional voluntary filing of SARs. SAR filing would be required for any transaction conducted or attempted by, at or through a broker-dealer involving (separately or in the aggregate) funds or assets of $5,000 or more for which (i) the broker-dealer detects any known or suspected federal criminal violation 10 involving the broker-dealer or (ii) the broker-dealer knows, suspects, or has reason to suspect that the transaction (a) involves funds related to illegal activity, (b) is designed to evade the regulations, or (c) has no business or apparent lawful purpose and the broker-dealer knows of no reasonable explanation for the transaction after examining the available facts, including the background and possible purpose of the transaction. The proposed regulations for SAR reporting under the Act are consistent with the suspicious activity reporting standards of the current federal regulations with one notable exception. Current regulations involve a two-tiered reporting system, under which SARs must be filed for $5,000 violations where a suspect can be identified and $25,000 violations where a suspect cannot be identified. The proposed rules do not adopt this two-tiered approach. SAR requirements also may be expanded to other types of entities. In this regard, the Act states that the Secretary may (as opposed to must) issue regulations extending mandatory SAR reporting requirements to CFTC-regulated entities, after consultation with the CFTC, and does not set any deadline for the Secretary to act. In addition, the Secretary, the SEC, and the Fed must, by October 26, 2002, jointly submit a report to Congress on recommendations for effective regulations extending SAR reporting to registered investment companies, including private investment companies under Sections 3(c)(1) and (7) of the Investment Company Act of 1940. Guidelines for Compliance Before the Act was passed, the SEC staff provided some helpful guidance on the nature of suspicious activities in the context of the staffs examination of broker-dealers. The staff advised that broker-dealers should be wary of the following practices: n The customer wishes to engage in transactions that lack business sense, apparent investment strategy, or are inconsistent with the customers stated business/strategy or prior investment history. KIRKPATRICK & LOCKHART LLP ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING UPDATE n n n n n n n n n n n n n n The customer exhibits unusual concern for secrecy, particularly with respect to his identity, type of business, assets or dealings with firms. Upon request, the customer refuses to identify or fails to indicate a legitimate source for his funds and other assets. The customer exhibits a lack of concern regarding risks, commissions, or other transaction costs. The customer appears to operate as an agent for an undisclosed principal, and is reluctant to provide information regarding that entity. The customer has difficulty describing the nature of his business. The customer lacks general knowledge of his industry. For no apparent reason, the customer has multiple accounts under a single name or multiple names, with a large number of inter-account or third-party transfers. The customer, or a person publicly associated with the customer, has a questionable background including prior criminal convictions. The customer account has unexplained or sudden extensive wire activity, especially in accounts that had little or no previous activity. The customers account shows numerous currency or cashiers check transactions aggregating to significant sums. The customers account has a large number of wire transfers to unrelated third parties. The customer is from or has accounts in, or has wire transfers to or from, a bank secrecy haven country or country identified as a money laundering risk. The customers account indicates large or frequent wire transfers, immediately withdrawn by check or debit card. The customers account shows a high level of account activity with very low levels of securities transactions. JANUARY 2002 Determining whether many of these activities are in fact suspicious is a line-drawing exercise particularly problematic for on-line brokers or other brokers who generally do not have face-to-face interaction with customers. Accordingly, broker-dealer training programs should sensitize employees to the new requirements under the Act, what money laundering is, how it is done, what activities should raise concern, and what steps should be followed when suspicions arise. SAR reporting may also place additional strains on broker-client relationships. SAR reports can and do trigger governmental investigations of a client, which in turn can damage a clients reputation and financial relations. In this connection, banks, thrifts and broker-dealers may freeze or close accounts and refuse further business with clients if they receive subpoenas investigating potentially criminal activity. While it is true that entities filing SARs are prohibited from informing the customer at the time they make the report, and broker-dealers making voluntary or mandatory SAR disclosures to the government enjoy broad immunity from liability, broker-dealers should reevaluate their privacy disclosures to ensure that clients are informed beforehand of the broker-dealers general reporting obligations. Primary Money Laundering Concerns One of the Acts more novel provisions allows the Secretary, in consultation with the Secretary of State and the Attorney General, to identify foreign jurisdictions, foreign financial institutions, classes of transactions within or involving a foreign jurisdiction, and types of accounts14 posing a primary money laundering concern (PMLC) and to impose special measures to require heightened due diligence for any transaction or account that involves a PMLC. Substance of the Requirement The Act identifies 5 types of special measures available to the Secretary in dealing with a PMLC. Flexibility is built in to permit the Secretary to impose any of the special measures (other than that relating to the restriction or prohibition of accounts) for a Kirkpatrick & Lockhart LLP 11 period of 120 days by order or any other manner permitted by law. Otherwise, the special measures can only be imposed by regulation. Record Keeping and Reporting. The Secretary may require a financial institution to maintain records and/ or file reports documenting transactions involving a designated PMLC. This could require financial institutions to create and maintain records at the time, in the manner, and for the period of time determined by the Secretary. In accordance with procedures established by the Secretary, such records must, at a minimum, include: (i) the identity and address of the participants in a transaction or relationship, including the identity of the originator of any funds transfer; (ii) the legal capacity in which a participant in any transaction is acting; (iii) the identity of the beneficial owner of the funds involved in any transaction; and (iv) a description of any transaction. Information Relating to Beneficial Ownership. The Secretary may require a financial institution to take reasonable steps to identify the beneficial owners of an account held in the US by a foreign person or its representative (other than publicly traded foreign entities) that involves a PMLC. The Act directs the Secretary to issue regulations defining beneficial ownership of an account, as used in the Act, that address an individuals authority to fund, direct or manage the account, as well as an individuals material interest in the account. Information Relating to Payable-Through Accounts. The Secretary may require any financial institution that opens or maintains in the US a payable-through account15 for a PMLC to: (A) identify each customer, and its representative, who is permitted to use or whose transactions are routed through such payable-through account; and (B) obtain information that is substantially comparable to that which the depository institution obtains in the ordinary course of business with respect to domestic customers. This includes information such as the name, address, and a taxpayer identification number and, for a business account, account authorization resolutions, incumbency certificates, and business identification information. 12 Information Concerning Certain Correspondent Accounts. The Secretary may require any financial institution that opens or maintains in the US a correspondent account for a PMLC to: (A) identify each customer, and its representative, who is permitted to use or whose transactions are routed through such correspondent account; and (B) obtain information that is substantially comparable to that which the depository institution obtains in the ordinary course of business with respect to domestic customers. This includes the name, address, and a taxpayer identification number and, for a business account, account authorization resolutions, incumbency certificates, and business identification information. Prohibitions or Conditions on Opening or Maintaining Certain Correspondent or PayableThrough Accounts. The Secretary may, in consultation with the Secretary of State, the Attorney General and the Chairman of the Fed, prohibit or impose conditions upon the opening or maintaining in the US of a correspondent account or a payablethrough account by any domestic financial institution or domestic financial agency for or on behalf of a foreign banking institution if such correspondent account or payable-through account involves any jurisdiction, financial institution or class of transaction that has been designated a PMLC. Guidelines for Compliance What makes compliance with these provisions particularly difficult is the absence of any helpful guidance in the Act or its legislative history as to what is meant by a transaction involving a PMLC. Broadly construed, this concept could include any transaction with any entity in a foreign jurisdiction designated a PMLC, or it could be construed narrowly to mean any transaction with a governmental authority in a foreign jurisdiction. From a practical standpoint, it will be up to the Secretary to clearly describe each type of transaction so designated in order for a financial institution to implement the appropriate response. Congress instructed the Secretary, in fashioning regulatory guidance, to require all US financial institutions to use greater care when allowing any KIRKPATRICK & LOCKHART LLP ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING UPDATE foreign financial institution inside the US financial system. Hence, it will be incumbent upon non-bank financial institutions, such as broker-dealers and investment companies, to include in their anti-money laundering programs systems to monitor for PMLC designations and implement the special measures that the Secretary may impose. For correspondent accounts and payable-through accounts, a financial institutions procedures should require the maintenance of records identifying each customer who is permitted to use the account and records including account information that is typically obtained by the financial institution in the course of business with domestic customers. Antimoney laundering programs should require a financial institution to maintain transaction records and beneficial ownership information for accounts held by foreign jurisdictions and foreign financial institutions. VIII. PENALTIES FOR NON-COMPLIANCE; EXPANDED IMMUNITY FOR SAR REPORTING Failure to follow the new provisions of the Act could carry severe consequences. The Act authorizes the imposition of a civil money penalty or criminal fine of up to $1,000,000. Since these penalties appear to apply separately to each violative transaction, there could be substantial potential exposure should a financial institution, for example, allow a prohibited shell bank to funnel multiple transactions through a correspondent account or allow a financial institution connected with a PMLC jurisdiction to open and maintain a correspondent account. At the same time, the Act clarifies the extent of the immunity from liability for disclosure for SAR reporting in two respects. First, it makes explicit that such immunity extends to voluntary reports to a governmental authority. This should provide added comfort to broker-dealers and other financial institutions that decide to voluntarily report suspicious activities before mandatory SAR reporting is imposed on them. The Act extends this immunity to liability under any contract or other legally enforceable agreement (including any arbitration agreement). Again, this should provide added comfort to broker-dealers that have arbitration clauses in customer account opening documents. JANUARY 2002 IX. BALANCING NATIONAL SECURITY V. PRIVACY Information Sharing The Act provides, effective immediately, that financial institutions and financial trade associations, after giving notice to Treasury, may share information with one another regarding individuals, entities, organizations, and countries suspected of possible terrorist or money laundering activities. The Act further provides that compliance with the information sharing provisions of the Act generally will not constitute a violation of the privacy provisions of Gramm-Leach-Bliley. The Act requires Treasury to issue regulations, by February 23, 2002, to encourage further cooperation among financial institutions, their regulatory authorities and law enforcement authorities, for the purpose of sharing information regarding individuals, entities, and organizations engaged in or suspected of terrorist acts or money laundering activities. Among other things, the regulations may require financial institutions to designate points of contact for information sharing and account monitoring. They may also require financial institutions to develop and implement procedures for protecting information. Government Surveillance Other provisions of the USA Patriot Act direct the head of the US Secret Service to take appropriate actions to develop a national network of electronic task forces throughout the country. The main thrust of this initiative is the prevention, detection and investigation of various forms of electronic crimes, including potential terrorist attacks against critical technological infrastructures and financial systems. The USA Patriot Act also broadens presidential authority under the International Emergency Powers Act, enabling the government to seize the property of any foreign person, organization or country that the president determines was used to plan, authorize, aid or engage in armed hostilities or attacks against the US. Under this provision, the President may confiscate not only financial assets and real property of suspected terrorists, but also computers and other hardware, computer files and related software, and whatever other components of technological Kirkpatrick & Lockhart LLP 13 infrastructures and network systems that the government believes were used to facilitate terrorist activity. The USA Patriot Act amends the principal federal privacy and surveillance laws to allow the government greater access to the publics personal information in the furtherance of investigations, both for terrorism and otherwise, and to allow greater sharing of this information among investigative agencies at federal, state and local levels. It also amends existing search warrant law to allow for roving warrants to intercept wire, oral and electronic communications, among other things. The government now may exercise broad investigative authority under the USA Patriot Act to intercept communications by any suspected terrorist or terrorism accomplice, with access to any financial, telephone or computer system or network used by such suspects. Privacy Concerns The interrelationship between permissible information sharing under the Act and the privacy provisions under Gramm-Leach-Bliley present difficult issues for financial institutions, both in terms of recognizing a proper balance of these competing public policies as well as maintaining strong customer relations. Financial institutions should be mindful of the Acts requirements for information sharing in establishing and enforcing their privacy policies, and should be flexible as legal requirements continue to evolve in this area. The USA Patriot Act, in its entirety, presents a multitude of new weapons to aid intelligence and law enforcement communities in the fight against terrorism. At the same time, it also presents a new set of concerns for every business owner participating in todays technology driven marketplace. Generally, every US financial institution, telecommunications provider, e-business and high-tech company should operate under the assumption that its network could be susceptible to covert search by law enforcement agencies. Further, all such entities should assume that every foreign client who raises a suspicion of questionable ties to terrorist activity or funding may subject them to such investigation and scrutiny and plan accordingly. 14 Endnotes: 1 The Bank Secrecy Act definition of a financial institution includes: an insured bank; a commercial bank or trust company; a private banker; a US agency or branch of a foreign bank; an insured institution (replaced in the Act by credit union); a thrift institution; a registered broker or dealer; a broker or dealer in securities or commodities; an investment banker or investment company; a currency exchange; an issuer, redeemer, or cashier of travelers checks, checks, money orders, or similar instruments; an operator of a credit card system; an insurance company; a dealer in precious metals, stones, jewels; a pawnbroker; a loan or finance company; a travel agency; a licensed sender of money; a telegraph company; a business engaged in vehicle sales, including automobile, airplane, and boat sales; persons involved in real estate closings and settlements; the United States Postal Service; certain governmental agencies; a casino, gambling casino, or gaming establishment with an annual gaming revenue of more than $1,000,000; other businesses designated by regulation. 2 Up to now, the federal government principally has relied on two reporting regimes to detect and prevent money laundering: (a) reporting of currency transactions over $10,000 on Currency Transaction Reports (CTRs) with the Department of the Treasury (Treasury) or on Form 8300 with the IRS (which also includes transactions in cash equivalents in certain circumstances) and (b) reporting of suspicious activities to Treasury through filing Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs). 3 Gramm-Leach-Bliley defines federal functional regulator as meaning: the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency; the Board of Directors of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation; the Director of the Office of Thrift Supervision; the National Credit Union Administration Board; the Securities and Exchange Commission. The Act also includes the Commodities Futures Trading Commission in the definition of federal functional regulator for purposes of the Act only. 4 The Act defines a correspondent account with respect to a bank as an account established to receive deposits from, or make payments on behalf of, a foreign financial institution or handle other financial transactions related to such institution. 5 Physical presence is defined in the Act as a place of business that (i) is maintained by a foreign bank; (ii) is located at a fixed address (other than solely an electronic address) in a country in which the foreign bank is authorized to conduct banking activities, at which location the foreign bank employs one or more individuals on a fulltime basis and maintains operating records related to banking activities; and (iii) is subject to inspection by the banking authority which licensed the foreign bank to conduct banking activities. 6 Congress included this exception to the shell bank prohibition to permit US financial institutions to do business with shell branches of large, established banks on the understanding that the bank regulator of the large, established bank will also supervise the established banks branch offices worldwide, including any shell branch. In KIRKPATRICK & LOCKHART LLP ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING UPDATE considering this provision, Congress cautioned financial institutions not to abuse this exception, to exercise both restraint and common sense in using it, and to refrain from doing business with any shell operation that is affiliated with a poorly regulated bank. 7 The Federal Deposit Insurance Act defines appropriate Federal banking agency as the Comptroller of the Currency, in the case of any national banking association, any District bank, or any Federal branch or agency of a foreign bank; the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, in the case of, among other things, any state member insured bank (except a District bank), certain foreign banks and branches or agencies of a foreign bank, and any bank holding company and any subsidiary of a bank holding company (other than a bank); the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in the case of a State nonmember insured bank (except a District bank), or an insured branch of a foreign bank; and the Director of the Office of Thrift Supervision in the case of any savings association or any savings and loan holding company. 8 Treasury stated that such broker-dealer accounts would include, among others, the following: (1) accounts to purchase, sell, lend or otherwise hold securities, either in a proprietary account or an omnibus account for trading on behalf of the foreign banks customers on a fully disclosed or non-disclosed basis; (2) prime brokerage accounts that consolidate trading done at a number of firms; (3) accounts for trading foreign currency; (4) various forms of custody accounts for the foreign bank and its customers; (5) overthe-counter derivatives accounts; and (6) futures accounts to purchase futures, which would be maintained primarily by broker-dealers that are duly registered as futures commission merchants. 9 The proposed regulations define an owner as any large direct owner, indirect owner, and reportable small direct owner. Under the proposed regulations, a large direct owner of a foreign bank would be a person who: (i) [o]wns, controls, or has power to vote 25 percent or more of any class of voting shares or other voting interests of the foreign bank; or (ii) [c]ontrols in any manner the election of a majority of the directors (or individuals exercising similar functions) of the foreign bank. A small direct owner would be a person who owns, controls, or has power to vote less than 25 percent of any class of voting shares or other voting interests of the foreign bank. A reportable small direct owner would be (A) [e]ach of two or more small direct owners who in the aggregate own 25 percent or more of any class of voting shares or other voting interests of the foreign bank and are majority-owned by the same person, or by the same chain of majority-owned persons; and (B) [e]ach of one or more small direct owners who are majority-owned by another small direct owner and in the aggregate all such small direct owners own 25 percent or more of any class of voting shares or other voting interests of the foreign bank. The proposed regulations indicate that in determining who is a reportable small direct owner a small direct owner who owns or controls less than 5 percent of the voting shares or other voting interests of the JANUARY 2002 foreign bank need not be taken into account. The proposed rules define an indirect owner as: (A) [a]ny person in the ownership chain of any large direct owner who is not majority-owned by another person; [and] (B) [a]ny person, including a small direct owner who is a majority-owner . . . in the ownership chain of any reportable small direct owner who is not majority-owned by another person. The proposed rules indicate that a person who is a reportable small owner need not also be reported as an indirect owner. 10 A private banking account is defined by the Act as an account (or combination of accounts) requiring a minimum aggregate balance of $1,000,000 (a) established by or on behalf of one or more individuals with a direct or beneficial ownership interest in the account and (b) assigned to or administered or managed, in whole or in part, by an officer, employee or agent of a financial institution who acts as a liaison between the financial institution and the direct or beneficial owner of the account. Congress intended accounts opened with balances of less than $1,000,000 that subsequently exceed the threshold and accounts with balances of $1,000,000 or more that subsequently fall below the threshold to be included. 11 See footnote 4, above. 12 Congress cautioned that other categories of foreign financial institutions will also require use of enhanced due diligence policies, procedures and controls including, for example, offshore broker-dealers or investment companies, foreign money exchanges, foreign casinos, and other foreign money services businesses. 13 The 19 countries currently on the FATF list are: Cook Islands; Dominica; Egypt; Grenada; Guatemala; Hungary; Indonesia; Israel; Lebanon; Marshall Islands; Myanmar; Nauru; Nigeria; Niue; Philippines; Russia; St. Kitts and Nevis; St. Vincent and the Grenadines; Ukraine. 14 The Act defines an account, with respect to a bank, as a formal banking or business relationship established to provide regular services, dealings, and other financial transactions; and includes a demand deposit, savings deposit, or other transaction or asset account and a credit account or other extension of credit. It directs the Secretary, after consultation with the appropriate federal functional regulators, to define by regulation the meaning of the term account for non-bank financial institutions, to the extent appropriate. 15 A payable-through account is defined as an account . . .opened at a depository institution by a foreign financial institution by means of which the foreign financial institution permits its customers to engage, either directly or through a sub-account, in banking activities usual in connection with the business of banking in the United States. The Act directs the Secretary, after consultation with the appropriate federal functional regulators, to define by regulation the meaning of payable-through account for non-bank financial institutions. Kirkpatrick & Lockhart LLP 15 Kirkpatrick & Lockhart LLP has diverse experience in issues involving or related to money laundering to help banking and diversified financial services clients assess their risk, establish and review compliance practices, investigate potential weaknesses, perform internal investigations, and respond to regulatory inquiries and enforcement actions while being sensitive to the privacy of each client and their customers through an effective attorney-client privilege relationship. If you have any questions about how the Act applies to non-bank financial institutions or banks, please contact one of the members of our interdisciplinary anti-money laundering practice team. While the group has over 50 attorneys firmwide, the selected members below focus their practice on financial institution compliance issues. BOSTON PITTSBURGH Michael S. Caccese D. Lloyd Macdonald Stanley V. Ragalevsky 617.261.3133 617.261.3117 617.261.9203 Mark A. Rush 412.355.8333 SAN FRANCISCO Jonathan David Jaffe David Mishel HARRISBURG Raymond P. Pepe 415.249.1023 415.249.1015 717.231.5988 WASHINGTON LOS ANGELES William J. Bernfeld William P. Wade 310.552.5014 310.552.5071 Diane E. Ambler James E. Day Kathy Kresch Ingber Robert A. Wittie 202.778.9886 202.778.9228 202.778.9015 202.778.9066 NEW YORK Richard D. Marshall 212.536.3941 Kirkpatrick & Lockhart LLP Challenge us. BOSTON n DALLAS n HARRISBURG n LOS ANGELES n MIAMI n NEWARK n NEW YORK n PITTSBURGH n SAN FRANCISCO n WASHINGTON ......................................................................................................................................................................... This publication/newsletter is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting with a lawyer. © 2002 KIRKPATRICK & LOCKHART LLP. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.