How effective is the "Wonderful Words" intervention

How effective is the "Wonderful Words" intervention programme at teaching target vocabulary?

Hannah Dyson (PhD Researcher)

Professor Charles Hulme (Principal Supervisor)

Developmental Science Department

1. INTRODUCTION

Children’s vocabulary levels are strongly linked to current and future educational performance (Lee,

2011).

A vocabulary gap exists between higher and lower achievers, which impacts negatively on educational attainment and therefore on life chances (Biemiller, 2012).

Researchers and practitioners have concluded that vocabulary needs to be taught explicitly in classrooms in order to address this gap (Beck, McKeown and Kucan, 2002).

The “Wonderful Words” programme was therefore developed to equip teachers with a ready-made vocabulary building programme.

Research Questions:

1.

Is the “Wonderful Words” intervention programme effective at teaching target vocabulary?

2.

Does the “Wonderful Words” programme have an effect on general vocabulary development, thereby helping to close the vocabulary gap?

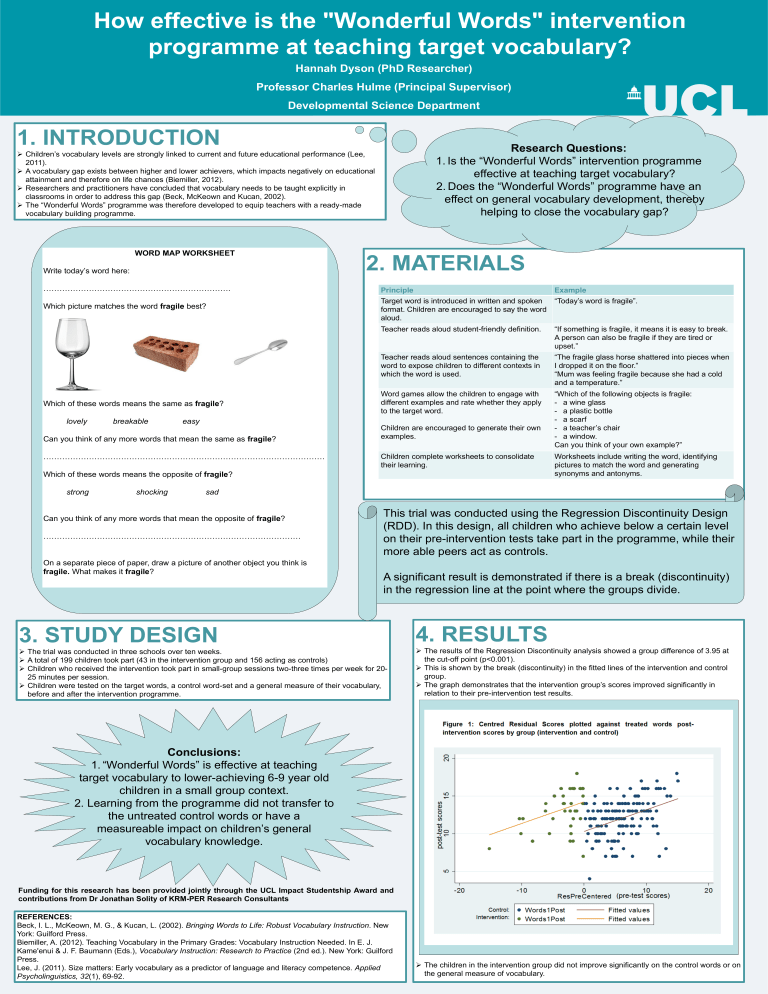

WORD MAP WORKSHEET

Write today’s word here:

…………………………………………………………….

Which picture matches the word fragile best?

Which of these words means the same as fragile ?

lovely breakable easy

Can you think of any more words that mean the same as fragile ?

……………………………………………………………………………………………

Which of these words means the opposite of fragile ?

strong shocking sad

Can you think of any more words that mean the opposite of fragile ?

……………………………………………………………………………………

On a separate piece of paper, draw a picture of another object you think is fragile. What makes it fragile ?

3. STUDY DESIGN

Conclusions:

1.

“Wonderful Words” is effective at teaching target vocabulary to lower-achieving 6-9 year old children in a small group context.

2. Learning from the programme did not transfer to the untreated control words or have a measureable impact on children’s general vocabulary knowledge.

2. MATERIALS

The trial was conducted in three schools over ten weeks.

A total of 199 children took part (43 in the intervention group and 156 acting as controls)

Children who received the intervention took part in small-group sessions two-three times per week for 20-

25 minutes per session.

Children were tested on the target words, a control word-set and a general measure of their vocabulary, before and after the intervention programme.

REFERENCES:

Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2002).

Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction

. New

York: Guilford Press.

Biemiller, A. (2012). Teaching Vocabulary in the Primary Grades: Vocabulary Instruction Needed. In E. J.

Kame'enui & J. F. Baumann (Eds.),

Vocabulary Instruction: Research to Practice

(2nd ed.). New York: Guilford

Press.

Lee, J. (2011). Size matters: Early vocabulary as a predictor of language and literacy competence.

Applied

Psycholinguistics, 32

(1), 69-92.

Principle

Target word is introduced in written and spoken format. Children are encouraged to say the word aloud.

Example

“Today’s word is fragile”.

Teacher reads aloud student-friendly definition. “If something is fragile, it means it is easy to break.

A person can also be fragile if they are tired or upset.”

Teacher reads aloud sentences containing the word to expose children to different contexts in which the word is used.

“The fragile glass horse shattered into pieces when

I dropped it on the floor.”

“Mum was feeling fragile because she had a cold and a temperature.”

Word games allow the children to engage with different examples and rate whether they apply to the target word.

Children are encouraged to generate their own examples.

“Which of the following objects is fragile:

- a wine glass

- a plastic bottle

- a scarf

a teacher’s chair

- a window.

Can you think of your own example?”

Children complete worksheets to consolidate their learning.

Worksheets include writing the word, identifying pictures to match the word and generating synonyms and antonyms.

This trial was conducted using the Regression Discontinuity Design

(RDD). In this design, all children who achieve below a certain level on their pre-intervention tests take part in the programme, while their more able peers act as controls.

A significant result is demonstrated if there is a break (discontinuity) in the regression line at the point where the groups divide.

Funding for this research has been provided jointly through the UCL Impact Studentship Award and contributions from Dr Jonathan Solity of KRM-PER Research Consultants

4. RESULTS

The results of the Regression Discontinuity analysis showed a group difference of 3.95 at the cut-off point (p<0.001).

This is shown by the break (discontinuity) in the fitted lines of the intervention and control group.

The graph demonstrates that the intervention group’s scores improved significantly in relation to their pre-intervention test results.

The children in the intervention group did not improve significantly on the control words or on the general measure of vocabulary.