Court Recognizes Telecommuting as a

Reasonable Accommodation

Sixth Circuit sides with employee who wanted to work from home

part of the week.

Amy L. Groff, The National Law Journal

November 10, 2014

Is telecommuting a reasonable accommodation under the Americans with Disabilities Act? With advances in

technology, telecommuting is becoming easier and more popular for employees, which has shaped how courts

view telecommuting when considering whether it is a reasonable accommodation for an employee with a

disability. Earlier decisions recognized physical presence as a necessary element for most jobs, but recent case

law makes clear that employers should no longer rely on that presumption.

Reprinted with permission from the November 10, 2014, edition of The National Law Journal. ©2014 ALM Media

Properties, LLC. Futher duplication without permission is prohibited. All rights reserved.

Telecommuting, which can include working from home and various other remote-workplace arrangements,

should not be overlooked as an accommodation that, in some circumstances, could be required under the ADA.

This article explores developments in this changing area of law, as highlighted by a recent decision by the U.S.

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, and will outline some factors to consider when deciding whether to

allow employees to telecommute.

In April, the Sixth Circuit's decision in U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Ford Motor

Co. brought increased attention to telecommuting as a potential accommodation. In Ford Motor, the court

reversed the district court's grant of summary judgment to the employer on an ADA failure-to-accommodate

claim involving an employee's request to work from home. However, in August, the court granted rehearing en

banc, and the en banc decision is pending.

The employee in Ford Motor worked as a resale steel buyer, and she suffered from debilitating irritable bowel

syndrome. It was not disputed that her condition was a disability within the meaning of the ADA. As an

accommodation, she sought to work from home up to four days a week. Ford rejected that proposed

accommodation because her position involved team work and client interaction that it believed required faceto-face meetings.

Specifically, as a resale steel buyer, the employee served as an intermediary between steel suppliers and the

companies that used steel to produce parts for Ford, and she had to respond to emergency supply problems and

interact with members of the retail team, suppliers and others in the Ford system. Thus, Ford's argument was

that physical presence in the workplace was an essential function for her position and that, because she was

unable to be present, she was not "qualified" for the position. Ford also argued that the proposed

telecommuting accommodation was unreasonable because, in its business judgment, the required meetings

were best handled face-to-face, and email or teleconferencing were insufficient substitutes for in-person

problem solving.

A Sixth Circuit panel disagreed with Ford. In a 2-1 decision, the court held there was a genuine question of

material fact as to whether the employee could perform her job duties from a remote location. That conclusion

was in sharp contrast to case law from the 1990s finding that it was an unusual case when an employee could

effectively perform all work duties at home and when telecommuting would, thus, be a reasonable

accommodation. Recognizing its divergence from earlier case law, the Sixth Circuit explained that the world

has changed since the foundational opinions addressing physical presence in the workplace and that

teleconferencing technologies are now commonplace.

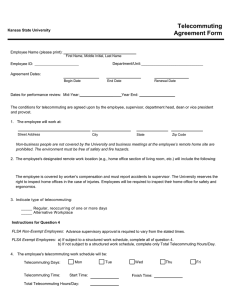

Another consideration in the case was the existence of a telecommuting policy at Ford. That policy allowed all

salaried employees to apply for a telecommuting arrangement, although it specified that such arrangements

were not appropriate for all jobs, employees, work environments or managers. The EEOC pointed to the policy

and the fact that Ford had allowed resale buyers in other situations to telecommute as support for its position

that this employee's requested accommodation was reasonable.

UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

Judge David McKeague's dissenting opinion pointed out that such reasoning and the majority's opinion would

have the unintended consequence of causing employers to tighten their telecommuting policies, to the

detriment of many other employees who benefitted from those policies. In his words, "the lesson for

companies from this case is that, if you have a telecommuting policy, you have to let every employee use it to

its full extent, even under unequal circumstances, even when it harms your business operations, because if you

fail to do so, you could be in violation of the law."

It will be interesting to see how the Sixth Circuit en banc addresses this policy argument. When the EEOC

published final regulations implementing the ADA Amendments Act in 2011, the preamble touched on

telecommuting. In describing the benefits of accommodations attributable to the statute and regulation, the

preamble noted that flexible work arrangements, such as flexible scheduling and telecommuting, can reduce

absenteeism, lower turnover, improve the health of workers and increase productivity.

Another interesting issue for the en banc court will be the question of how much deference to give the

employer's business judgment that in-person interaction is an essential function of the employee's position. The

district court expressly declined to "second-guess" the employer's business judgment regarding the essential

functions of the job, but the Sixth Circuit took a more critical look at whether the interaction really had to be in

person given the communication technology available today.

Under existing regulations, the business judgment of an employer is a factor to be considered in determining

whether an aspect of a job, such as presence at a fixed worksite or some other duty, is an essential function.

Other considerations include the written job description, the amount of time spent performing the function, the

consequences of not requiring the employee to perform the function, the collective bargaining agreement (if

any) and the work experience of other employees in the same or similar positions. 29 C.F.R. 1603.2(n)(2). The

extent to which the en banc court relies on the employer's business judgment regarding essential functions

could have significant ramifications in the context of telecommuting requests — and for other accommodation

requests, as well.

In the meantime, what is clear is that employers will not be granted unfettered discretion to designate certain

functions as essential and that there is no one-size-fits-all solution for most businesses when it comes to

telecommuting requests. In an informal discussion letter released earlier this year, the EEOC criticized

language in a sample policy stating that "working from home is 'generally' not a reasonable accommodation

'except in extraordinary circumstances.'" The EEOC's letter cautioned that the law is far from settled in this

area and that policies suggesting that telecommuting is required only under extraordinary circumstances may

lead an employer to violate the ADA.

On the other hand, the EEOC has acknowledged — in its informal discussion letter and in other written

guidance — that telecommuting is not appropriate for all jobs and that an employer may select another

effective accommodation when one is available. Thus, employers may be able to resolve certain

telecommuting requests by providing a different type of accommodation that likewise accommodates the

employee's condition and allows her to perform the job at the worksite.

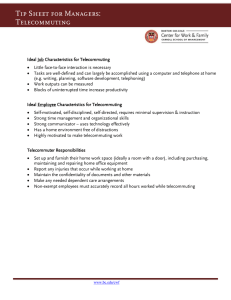

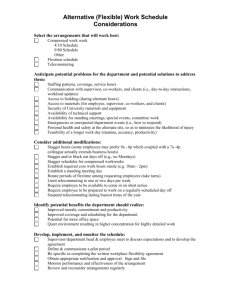

In light of the expanded definition of "disability" under the ADA Amendments Act of 2008, more employees

are covered by the statute, making the question of telecommuting as a reasonable accommodation a question

employers will face more frequently than in past decades. And with any remote-workplace arrangement,

employers may have additional issues to consider, such as data security, potential workers' compensation

liability for injuries sustained while working at home, supervision and control of the work performed and

proper tracking of compensable time for nonexempt employees who are subject to overtime and recordkeeping requirements.

It may be possible for employers to argue that unique burdens associated with some of these remote-workplace

issues impose an "undue burden" on their business such that a telecommuting accommodation is not

reasonable. An example involving data security is a government employee whose job could only be performed

at a secure clearance center, for which the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit upheld the denial of a

telecommuting request in 2010. However, apart from jobs like that — or food servers, retail clerks, truck

drivers and other jobs that clearly cannot be performed at home — there is a vast gray area in which employers

may need to consider whether telecommuting would be a reasonable accommodation required by the ADA. As

technology advances, and as courts continue to address changes in technology, this will certainly be an area of

law to watch.

Amy L. Groff is a partner in the Harrisburg, Pa., office of K&L Gates. Her practice involves employment law,

general civil and commercial litigation, and appellate work.