Biology of language: A Milestone beyond the Quinean turn

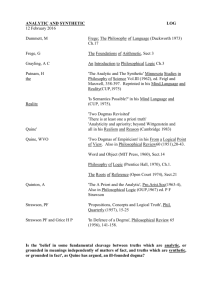

advertisement