Experiential Learning in Sociology: Service Learning and Other Community-Based Learning Initiatives

advertisement

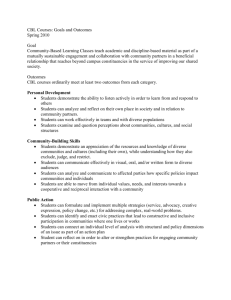

Experiential Learning in Sociology: Service Learning and Other Community-Based Learning Initiatives Author(s): Linda A. Mooney and Bob Edwards Source: Teaching Sociology, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Apr., 2001), pp. 181-194 Published by: American Sociological Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1318716 . Accessed: 10/04/2013 06:41 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. . American Sociological Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Teaching Sociology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 137.205.95.22 on Wed, 10 Apr 2013 06:41:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions EXPERIENTIALLEARNINGIN SOCIOLOGY: SERVICELEARNINGAND OTHER COMMUNITY-BASED LEARNINGINITIATIVES* Despite increased popularity and a strong pedagogical tradition, the literature on community-based learning (CBL)initiatives and service learningevidences a certain conceptual imprecision. In the hopes of clarifyingdefinitionalambiguities, we criticallyreview the CBLliterature,identifyingsix distinct types of CBL options and their characteristics. The result is a hierarchyof community-based learning, which while not proposed as a definitive conceptualization, is likely to be useful in terms of curriculardevelopment. Using a hypothetical sociology class, the community-based learning options identified (i.e., out-of-class activities, volunteering, service add-ons, internships, service learning, and service learningadvocacy) are discussed in terms of theirpedagogical differences and associated curricularbenefits. LINDA A. MOONEY East CarolinaUniversity BOBEDWARDS East CarolinaUniversity has threecomplemenTHE PRESENTRESEARCH BACKGROUND first is to undertake a critical The tarygoals. reflectionon recentservice-learningpraxis In recent years there has been increased in order to distill and synthesize current interestin studentvolunteeringand, more thinking.In so doing, we identifydistinct specifically,servicelearning(Chapin1998; learning(CBL) HinckandBrandell2000; ShumerandCook types of community-based and 1999; Wardand Wolf-Wendel2000). Seroptions,distinguishtheircharacteristics, develop a heuristicsynthesisand typology vice learningis an evolving pedagogythat that we hope will help clarify the ongoing incorporatesstudentvolunteeringinto the definitionaldebate.Second,we discussCBL dynamicsof experientiallearningand the optionswithinthe contextof a hypothetical rigorsandstructureof an academiccurricusociologycourse.Thisdiscussionis intended lum. In its simplestform, service learning to illustratethe pedagogicaldifferencesbe- entails studentvolunteeringin the commutweenlearningmethodologiesandcurricular nity for academiccredit. It is not a new benefits,typicallyassociatedwith particular concept. As early as 1902, John Dewey CBLoptions.Third,the typologydeveloped extolledthe valuesof a "progressiveeducabelow is intendedas a heuristicdevice to tion"-an educationwhere thoughtand acfacilitate dialogue and reflection among tioncome in classroomandreallife together those endeavoringto integratecommunity(Dewey 1938). based learninginto sociology courses and settings While not immediatelyembracedas a programsas well as among administrators philosophy,Dewey's principlesresurfaced and researchersseeking to evaluate their in by such practicein the 1960s,popularized impact. nationalserviceprogramsas VISTAandthe addressall correspondence "*Please to Linda Peace Corps. Studentactivism,and with it A. Mooney,Department of Sociology,East volunteering,wanedin the 1970s andearly CarolinaUniversity,Greenville,NC 27585; 1980s (ShumerandCook 1999),'but by the e-mail:MooneyL@mail.ecu.edu Editor'snote:The reviewerswere, in alphabeticalorder,KevinD. Everett,Anne Martin, andRachelR. Parker-Gwin. 'Brooks(1997:3)notesthatsociology alsofell victimto thetemporary loss of a volunteerethic: "In sociology the first signs of this change Vol.29, 2001(April:181-194) Teaching Sociology, This content downloaded from 137.205.95.22 on Wed, 10 Apr 2013 06:41:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 181 TEACHINGSOCIOLOGY 182 late 1980s, "serveandlearn"programshad needs than the "efficiency"of providing been resurrectedto renewed prominence additionalcredit hours with no additional of such umbrella facultycosts (Gose 1997). In contrast,longthroughthe establishment organizationsas CampusCompact,a na- term observersof school-societyrelations of college anduniversity likely see the currenttrend as simply the tionalcollaboration presidents"pledgedto encourageand sup- most recent ebb and flow in the tides of port academicallybased community ser- school reformthat seek alternatelyto intevice..." (Jacoby 1994:14). Bolstered by grate schooling more tightly with current PresidentBush's"thousand pointsof light," marketdemandsandto use formaleducation the 1990 Nationaland CommunityService as a tool of progressivesocialchange(Tyack Act, the Nationaland CommunityService andCuban1995).3 The renewedemphasison CBL can also Trust Act of 1993, and the 'Goals 2000' educationalinitiative,today CampusCom- be tracedto a strongpedagogicaltradition pact has over 600 institutionalmembers rootedin the worksof JohnDewey (1916; offering 11,800 service-learningcourses 1938) and WilliamJames (1907), and the (Finn and Vanourek1995; Perreault1997; more recent work of ErnestBoyer (1990; Rothman, Anderson and Schaefer 1998; 1994)andPauloFreire(1970; 1985). Boyer (1990; 1994), for example,arguesthatthe Bringleet al. 2000). shouldbe responsiveto commuthere such a renewed interhas been university Why est in and institutionalsupportfor service nity needs and to society as a whole, and learning,andwhatin generalmay be called that facultymembersshouldbe "reflective community-basedlearning (CBL)?2Some practitioners"in the education process. commentators pointto the rapidlychanging "Whatwe urgentlyneed today is a more social, political, and economic context of inclusive view of what it means to be a highereducation.For example,Marulloand scholar-a recognitionthat knowledge is Edwards(2000a) arguethat the globalizing acquiredthroughresearch,throughsyntheeconomy increasinglydemands "workers sis, throughpracticeand throughteaching" with symbol-manipulating skills," driving (Boyer 1990:24). Boyer's definition of to emphasize scholarshipthus questionsthe traditionally universities and colleges methodsthat promotecritical held notion that knowledgeis first discov"educational thinking,complexreadingandwritingskills, ered and then applied,askingthe question: and problem-solvingand conflict-resolution "Cansocial problemsthemselvesdefine an abilities"(p. 747). Citing similar trends, agendafor scholarlyinvestigation?" (Boyer more skepticalobserverssuggest that the 1990:21)His workhas "movedteachingand interestin community-based learning evi- service into the forefrontin higher educadencedby manyuniversitiesmay have less tion"(Brooks1997:3). to do with student,societal,or even market Not surprisingly,CBL options, all of whichcomeunderthe largerrubricof active whohadflockedto sociol- learningmethodologiesandspecifically,exas students appeared ogy in the late 1960sandearly1970sto learn how to solve the social problems of the time moved just as rapidly to the schools of business in the mid 1970s to learn skills that would get them a job 'andallow them to make money in an increasinglyunstableeconomy." 2Community-basedlearning refers to any pedagogical tool in which the communitybecomes a partner in the learning process. While all CBL initiativesare experiential,and in that way active learning, not all active learning techniques are experientialin nature. 3Otherinstitutionalpressures include concerns over the quality of undergraduateteaching, esoteric research agendas (Hinck and Brandell 2000; Jacoby 1996; Lena 1995; Marullo and Edwards2000a), apatheticand alienatedstudents (Wade 1997; Wallace 2000), an emphasis on materialism andindividual (Bellahet well-being al. 1985; Myers-Lipton 1998), and the nonresponsiveness of colleges and universities to community needs (Edgerton 1994; Edwards and Marullo 1999; Plater 1995; Ward 1996). This content downloaded from 137.205.95.22 on Wed, 10 Apr 2013 06:41:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING IN SOCIOLOGY perientiallearning,appealto socialscientists andsociologistsin particular(Corwin1996; and Mabry1998). Lena 1995; Parker-Gwin adhered First,sociologistshave traditionally to an "underdogideology" rooted in the social problems legacy of the Chicago School and the activism it promoted (Pestello et al. 1996). Second, given the abstractnatureof sociologicaltheoriesand concepts, faculty membershave turnedto the "realworld" in order to groundtheir disciplinein a frameworkto which students can relate. Indeed as Keith (1994:312) notes, experiential learning serves as a "mechanismto promotethe active involvementof studentsin a learningprocesswhich is integrativeandeschewsartificialdivisions betweendevelopmentaland academictasks and between classroom and life experiences." Finally, and relatedto the above, sociology's movementtoward an applied and practicaldiscipline(Brooks 1997) and the accompanyinguse of practica,co-ops, in helpingstudentsdo sociolandinternships ogy, providesa transitionto otherexperientiallearningoptions. However,despiteincreasedpopularityand a strong theoreticalfoundation,the CBL literatureevidencesa certainconceptualimprecision(FinnandVanourek1995). Definitionsof servicelearningaboundandrunthe gamut from such vague and all-inclusive definitionsas "academically-based service," to othersso narrowlyconceivedthat much of what is thoughtof as service learning wouldbe excludedfrom consideration.Becauseof its recentpopularity,the "servicelearning"labelis often appliedto any existing form of CBL, furthermuddyingthe ongoingdefinitionaldebate.Fortunately,the diversity verydefinitionalandprogrammatic lamentedby some commentatorsprovides the raw materialsneededto synthesizecurrentthinking. SERVICE LEARNING AND OTHER COMMUNITY-BASED LEARNING INITIATIVES Mintz and Hesser (1996) note that there is 183 debategoingon-a debateover an important what service learningis and, thus, how it shouldbe defined: to grapplewithandlearnabout We continue diverdiverseandsometimes servicelearning's is farfrombeing gentaspects,anda consensus reached.The debateaboutthe definitionof somestillquestion servicelearning continues; canbebothcocurricuwhether servicelearning of whoand lar andcurricular; classifications is oftendifwhatcompose"thecommunity" fuseandunclear;andthe distinctions among education, internships, practica,cooperative andservicelearning remain blurred (26). This problemof definitionwas empirically documentedby Hinck and Brandell(2000, see Table 1). The two researcherssurveyed 225 directorsof randomlyselectedservicelearning centers affiliated with Campus Compact.Askedto define servicelearning, the directors' responses varied significantly-"co-op education,""specializedinternshipcourses,""experiencegainedin the non-profitor governmentsector," "faculty requiringstudentsto takepartin community projectsand give credit in course work," and "community volunteerplacementsin an approvedsite"(p. 874). Kendall (1990) reports identifying 147 differenttermsassociatedwithservicelearning and other CBL options. For example, ShumerandBelbas(1996) includea variety of programsunderthe rubricof experiential/ service-learningprograms.They also use service learning and communitylearning interchangeably.Similarly, Parker-Gwin (1990) refersto service learningas one of manytypesof experientiallearning.Easterling and Rudell state that service learning can be "integratedin a varietyof...courses as internshipassignments,consultancies,or participant/observervolunteer activities" (1997:58),Enos andTroppe(1996) referto "service-learning internships," McCarthy (1996) discusses "one-time and short-term service-learning projects," and Shumer (1997), in a review article on the impact of service learning, includes such varied initiatives as internships, tutoring programs, ad- This content downloaded from 137.205.95.22 on Wed, 10 Apr 2013 06:41:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 184 TEACHINGSOCIOLOGY Figure1. Hierarchyof CommunityBasedLearning(CBL) CBLOptions Out-of-ClassVolunteering Service Activities Add-ons Internships Service Learning Social Action X Structured Reflection X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X Apply/AcquireSkills Curricular Credit Service Rendered In Community ServiceLearning Advocacy X venture education, mentoring, hospital field work, and dropoutprevention programs. For those who have had occasion to develop or oversee a variety of CBL options, the differences between internships, experiential learning, volunteering, cocurricular community service, preprofessional experiences, practica, co-ops, community service, and applied learning may seem to be relatively clear-cut. However, among faculty members and administratorsconsidering the full range of CBL endeavors for the first time, such distinctionsmay not be obvious. Marullo (1998), in his discussion of "bringing home diversity" in a race and ethnic relations class, describes three CBL options: service-learningcredits, group projects, and intensive service learning. Criteria Marullo identifies in distinguishing between the three learning types include variations in the service rendered, integration of out-ofclass experiences into the course, and level of curricular credit received for participation. Marullo's typology, however, is limited to the "three primary models to integrate community service into a course" available at Georgetown (1998:264). What is needed is an expansion of his continuum through the identification of conceptually distinct CBL initiatives. Fortunately, the service-learning literature reveals several common dimensions of service learning that distinguish it from other types of CBL. Figure 1 summarizes our categorization of these essential components. Figures 1 and 2 identify six CBL options, criteria for differentiating/between types, and benefits to students most likely to be associated with each initiative. Obviously, exceptions exist, and the boundariesbetween some types may be fuzzy. In practice, one service-learning program may be closer to an internshipand anotherto service-learning advocacy. Others still may not neatly fit the mold.4 It is worth emphasizing that our purpose in developing this typology is not to settle the current definitional debate by offering a definitive conceptualization.Rather, our aim is to help clarify the issues at stake in that debate and to facilitate reflection and dialogue among practitionersthat can lead to improved praxis. As Figure 1 suggests, moving from out-of-class activities to service-learning advocacy increases the 40Othersstill may not fit the mold at all. For example, Marullo's(1998) "GroupProjects," Parker-Gwinand Mabry's(1998) "Consultant Model," and Rundblad's(1998) "Community ExplorationProject"would be CBL hybrids accordingto ourtypology. This content downloaded from 137.205.95.22 on Wed, 10 Apr 2013 06:41:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions EXPERIENTIALLEARNINGIN SOCIOLOGY 185 structureand complexity of the learning Service learningis not simply volunteerexperienceas well as students'commitment ing...Manypeoplevolunteerin theircommunitieswithout theirbeliefsor critically examining to individualsandorganizations.It shouldbe the the need for such structural causes of noted that to meet the thresholdrequireservicesto exist.Simply"doing"is notsuffiments of service-learningadvocacy, CBL cientforlearning tooccur(1998:299). endeavorsneed to evidence the attributes listedin all six columnsof Figure1. ServiceAdd-On When studentparticipationresultsin addiOut-of-ClassActivities tionalcredit,as wheninstructorsoffer extra Fieldtripsareperhapsthe base line example creditor additional pointsfor volunteering, of out-of-classactivities. While most field sucha CBL is calleda serviceadd-on option tripstakeplacein a communitysetting,they (Jacoby1996). Similarto a "fourthcredit tendto be like havingclass somewhereelse, (Enos and Troppe 1996; Marullo as studentsgo on locationto hear a guest option" (i.e., three-hourclasses that become 1998) speakeror see an exhibit. Thoughstudents four-hourclasses when a volunteercomposeldomrenderservices,applyexistingskills, nent is added), whether tutoring second or engagein systematicreflectionwhile on in a city beautificaor participating graders field trips (for an exception see Scarce tion serviceadd-onstakeon another project, 1997), field tripsdo enablestudentsto see, dimensionof CBL-academiccredit. Since hear, and smell places and meet the people not all students in the may be participating who frequentthem. Studentswith no such often one of the disadvanexercise, optional priorexperiencesno longerhave to imagine tages of serviceadd-onsis the tendencyfor a place, its people,or its sights,sounds,and the volunteer activityto remainperipheralto smells. From field trips, a class shares a the if thereis relatively course,particularly stock of common images that facilitates low studentinvolvement.One potentialcomdiscussion and can foster camaraderie of add-ons is indirect.Stumunityimpact among studentsand between studentsand dentswho gain throughvolunteeringexperithe instructor. ences with add-onsmaywell be morelikely to do so again in anothercontext. Yet, Volunteering compared to more substantiveforms of Similarly, volunteeringmay be a course CBL, the directcommunityimpactof addrequirement,but rarely is additionalaca- ons is likely to be reduced because the demic credit offered for it as "thereis no serviceis optional,involvingfewer students explicitfocus on the educationalvalueto be thanin classeswherea servicecomponentis gainedthroughinvolvementin the particular requiredof all students.Moreover,the lim[volunteer]projects"(Waterman1997:3). ited durationof add-ons also suggests a also takesplace in the commu- reduced Volunteering community impact (Marullo but nity, contraryto out-of-classactivities, 1998:264)thanwitheithertraditional internassumes that some service has been proor the 10-month,20-hourper week ships, vided. Much like the traditionalnotion of service-learning placementsrequiredof the charity, volunteeringoften establishes a Washingtonstudy-serviceyear assessedby giver-receiver relationship as students Aberle-Grasse (2000). "help"othersdefinedas in need (Marullo and Edwards2000b; Perreault1997). VolInternships unteers, however, are unlikely to apply or enhance existing skills (e.g., handing out sandwiches at the local homeless shelter) or to engage in any organized and meaningful reflection (Hironimus-Wendt and LovellTroy 1999). As Everett notes: Internships, sometimes called practica, cooperative learning or field placements, are pre-professionalexperiences often offered as stand-alone courses (Hironimus-Wendtand Lovell-Troy 1999; Marullo 1996; 1998). Internships are a common component of This content downloaded from 137.205.95.22 on Wed, 10 Apr 2013 06:41:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 186 TEACHINGSOCIOLOGY sociologydepartments, particularlywith the 2000a; Roschelle,Turpinand Elias 2000; of applied sociology programs Rudell1996; Sax and Chapin1998; Watergrowth (Parillaand Hesser 1998). Studentsserve man 1997). the communityby relatingcourse content, Theintegration of servicelearningintothe and to real curriculum is a life dialectical skills, existing expertise processwhereby settings and receive credit for doing so. material appropriateto the content of a reflecStructuredreflection,however,is often not specificcourseis, throughstructured In structured with the into contrast, tion, ongoing experiential put dialogue required. reflection in general distinguishesservice inputfrom the service-learning setting, acfrom other CBL and and tivities, learning options(Enos communitypartners.Student Everett Fertman in 1998; 1994; experiences the service-learningsetting Trope 1996; Gardner1997; Gereand Sinor 1997; Giles, shapetheirunderstanding of coursecontent and Honnett and while the in Gronski course content turnshapestheir 1991; Migliori, Koulish of the kinds of socialcontexts 1998; understanding Pigg 2000; Jacoby 1996; Marullo1996; 1998;Migliore1991;Parker- and relationscharacteristic of theirserviceGwin and Mabry 1998; Perreault 1997; learningplacements.The sense of knowing Saltmarsh 1996; Sax and Astin 1997; thatemergesfromthis type of processtranShumerandBelbas1996;andWade1997).5 scends the knowledgeattainableby either masteringthecontentor independently expeServiceLearning riencingthe serviceplacement(Freire1973; The 1990 CommunityService Act defines Palmer 1983). Optimally,subsequentdiaservicelearningas a methodof learningin logues would includeindividualsrepresentwhich studentsrenderneeded services in ing both the organizationalhost of the theircommunities for academiccredit,using service-learningplacementand the benefiand enhancingexisting skills with time to ciaryconstituencyfromthe community.6 "reflecton the serviceactivityin sucha way as to gain further understandingof the is a crucialmeansfor 6Structured reflection coursecontent,a broaderappreciation of the facilitatingthe processsketchedabove.It entails discipline,and an enhancedsense of civic the integrationof both individualand group responsibility" (Bringle and Hatcher processes.For individuals,structuredreflection 1995:112). Although some commentators requiresstudentsto turnthe natureandresultof theirpriorreflectionintoan objectof subsequent questiontheextentto whichservicelearning critical reflection-individualmeta-reflection. must be integrated into the curriculum The goal of this activity,whichcan be accom(Fertman 1994; Jacoby 1996; Perreault plishedin part by journalling,is to critically 1997; Rubin 1996; Scheuermann1996; analyzeour own reflectionin orderto improve Ward and Wolf-Wendel2000), most pub- our criticalfaculties.Structuredreflectionalso lisheddefinitionsof servicelearningimplic- has a collectiveor groupaspectsuccinctlydeitly includethe first five componentsidenti- scribedas "sharedpraxisin praxis."We first in Groome thissuccinctdescriptor fied in Figure 1 (see, for example, Astin encountered 1997; Bringle and Hatcher 1995; Burns (1980)wherehe ablydiscussesfivemovements educational pedagogy.Though 1998; Fertman 1994; Gardner 1997; in a praxis-based from within a faith-based contextof articulated Howard1998;KahneandWestheimer1996; for socialjustice, this remainsone of educating Marullo[1996] 1998; Marulloand Edwards the more andaccessiblediscussionsof andWltizdorff (1988:15),indefin"5Hutchings ing reflectionas "the abilityto step back and pondersone's own experience,to abstractfrom it somemeaningor knowledgerelevantto other arguethat"thecapacityfor reflecexperiences," tion is what transformsexperienceinto learning." thorough the philosophical,psychological, and social basesof the educational approachsketchedhere. Forthoseseekingotherpointsof accessintothis long-standingpedagogicaltradition,see also Freire1974;HortonandFreire1990.Forparallel discussionsappliedto research,see Gaventa 1993;Merrifield1993;andPark1993. This content downloaded from 137.205.95.22 on Wed, 10 Apr 2013 06:41:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING IN SOCIOLOGY Advocacy Service-Learning As Figure 1 indicates,service-learningadvocacy requiressocial action wherebystudents become "citizen leaders" (Perreault 1997)througha "pedagogyof civic involvement" (Koulish 1998:563). Unlike service learningin general, service-learningadvocacy "shouldbe criticalof the statusquo, challengeunjuststructures,and oppressive institutionaloperations,and providean opsocialjustice portunityfor institutionalizing activism on college campuses" (Marullo 1996:117). Consistentwith Dewey's statementthat"schoolshavea role in the production of social change"(1937:409), servicelearning advocacy encouragesstudentsto becomeactorsin the dramaof producinga morejust society by takingchargeof their education,appropriatingcampus-basedresourcesavailableto them,andtakingcollective action to confrontthe root causes of socialinjustice.A key pedagogicalenhancement of service-learningadvocacyowes to its explicitsocialchangeagendathe assumption thatpeoplebeginto appreciatefully the relations of power in a society as they endeavorto affectsocial changein the context of criticalreflectionand dialoguewith otherswho are similarlyengaged. Advocatesof this position (e.g., Boyer 1983; Giles, Honnet, and Migliore 1991; Goodlad 1984; Koliba 2000; Newmann 1975; Wadeand Saxe 1996), respondingto an entrenchment of social problems(Boyer 1994:Jacoby1996;GronskiandPigg 2000; Wade 1997) caused in large part by economicglobalizationand the continuedwithdrawalof the state from responsibilityfor social welfare (Edwardsand Foley 1997), arenot withoutcritics.Givenits value-laden havenotedthat position,commentators 187 Clearly, each of the CBL optionsidentified is likely to be instituteddifferently dependingon faculty members'goals and institutionalresources. Variations within categoriesarealso likely. As practiced,each of the CBL optionsvary in termsof: 1) the number of studentsserved, 2) individual versus group involvement,3) optionalor 4) level of site superrequiredparticipation, vision, 5) class assignments,6) methodof evaluation,7) integrationof out-of-classexperiencesandcoursematerial,8) long- versus short-termcommitments(for example, weeks versusmonths),9) numberand type of communityorganizationsinvolved, and 10) the relationshipbetween the various constituencies-thedepartment,the community, the collegeor university,andthe organization(s)served.Whatthey have in common, however, is that each provides the benefitsof experientiallearning. curricular CURRICULARBENEFITSOF SERVICELEARNINGAND OTHERCOMMUNITY-BASED LEARNINGINITIATIVES Figure2 identifiespotentialbenefitsto students of using CBL options in sociology courses.Somehave arguedthatin orderfor "servicelearningto achieveits greatestpotential as an instructionalcomponent...a commondefinitionmustbe adopted"(Burns 1998:38). We disagree. Rather, we offer this typologyas a heuristicdevice to facilitate the reflectionand discussionof whatis involvedin integratingCBL initiativesinto teachingundergraduate sociology. As sugof the benefits gestedabove, types curricular from CBL gained participation vary directly as one moves up the hierarchyof CBL.7 7Studieson studentoutcomeshavelinkedservice learningandotherCBLoptionsto 1) better more effective learning, and student ...muchof whatpassesfor servicelearning grades, retention(Blyth,Saito, and Berkas1997; Boss involvespoliticalactivism.Butthatshouldnot 1994;CalabreseandSchumer1986;Conradand be surprising,because,in the eyes of its advo- Hedin 1982;Greco1992;Miller1994;Saxand cates,suchactivism-always,in practice,on the Astin 1997; Shumer1990; 1994; Waterman liberal-to-Left end of the politicalspectrum-is collaborationskills (Brandonand service learnings'most desirableform (Finn 1997); 2) Sax andAstin 1999; 1997);3) a stronger Knapp andVanourek1995:46) commitmentto service,volunteerism,andcivic This content downloaded from 137.205.95.22 on Wed, 10 Apr 2013 06:41:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 188 TEACHINGSOCIOLOGY While students participatingin service- experienceis anotherfaculty option. Stulearningadvocacywould stand to gain all dentsmaybe placedin relevantworksitesto benefitsthatwouldaccrueto thosein out-of- hone theirexistingskills or to acquirenew class activitiesor service add-ons,the re- ones. Ideally, it is here that studentsget verse is unlikely.Studentsengagedin more "hands on" practical experience as they substantive CBLoptionshavegreateroppor- applyabstracttheoriesand conceptsanduse tunityto experiencehigherordercurricular methodologicalskills at the work site. Debenefits. For example, internshipsafford of a needs assessmentsurveyof studentsmore opportunityto acquirenew velopment inmates, participationin a state-levelreskills thando field tripsor serviceadd-ons. searchprojecton juvenile delinquency,or By the sametoken,the greaterprevalenceof structuredreflection in service learning acting as a liaison between a community makesstudentsmorelikely to applycritical watch group and the police departmentis sure to help studentsunderstand coursemathinking,synthesizeinformationfrom classterial in a new the However, way. "learning roomand communitysettings,and examine of these activities focus objectives typically structural/institutional antecedentsof social issuesthanwouldtendto be the case among only on extendinga student'sprofessional skills, anddo not emphasizeto the student, volunteersor interns. of In teachingan upperdivisionsociologyof eitherexplicitlyor tacitly,the importance crimecourse,a facultymembermighthave servicewithinthe communityandlessonsof studentsinterviewpolice officers, take a civic responsibility"(Bringle and Hatcher tour of the local jail or observe a day in 1996:222). Service learning in such a class might court.Eachconstitutesan out-of-classactiventail studentsservingin a non-profitmediaand would facilitatestudentobservations ity of social actorsand their interactionsin a tion center. Working side by side in a socio-legal setting, ideally providing stu- collaborative effort, students, teachers, dentswith "reallife" examplesof material lawyers,mediationstaff, agencyvolunteers, presentedin class. Studentsmightalso have andcommunityleadersmight,for example, the opportunity to volunteeror to earnaddi- design and implementa school mediation tionalacademiccreditthroughserviceadd- program.Class assignmentswould include ons, for example,by tutoringincarcerated researchingthe social, historical,political, youths or preparingmeals at a halfway andeconomicforcesthatgaverise to mediahouse. These experiencescombine all the tion as an alternativeto traditionalmethods benefits of out-of-classactivitieswith the of adjudication.Studentswouldrecordobadditionalbenefitof providingstudentswith servationsin reflectivejournalentries,classa stock of experience,exposureto diverse room activitieswould be designedto help groups,and, perhapsa sense of satisfaction process out-of-classexperienceswithin the that comes from meeting the immediate context of course material, and critical needsof others.Suchexperiencesmay also thinkingandproblemsolvingskillswouldbe lead to an awarenessof communityneeds sharpenedby the everydayhurdlesof proIt is and a heightenedconsciousnessof social gramdevelopmentandimplementation. here that students a of sense develop issues. as are broadened An internship,practicum,or cooperative "knowing" perspectives andimportant linkagesaremade. Dependingon the desired curriculum responsibility (Blyth,Saitoand Berkas1997; Boss1994;RandEducation 1999;SaxandAstin skills" as increasedtoleranceof diversity, multimoraland cultural sensitivity, promotion of racial equality 1997;Waterman 1997);4) enhanced ethicalreasoning (Delve,Mintz,and Stewart and conflict resolution (Aberle-Grasse 2000; benefits 1990;Zlotkowski1996);5) employment (e.g., clarity in career path, networking, placement); and 6) the development of such "soft Blyth, Saito and Berkas 1997; Easterling and Rudell 1997; Myers-Lipton 1998; Zlotkowski 1996). This content downloaded from 137.205.95.22 on Wed, 10 Apr 2013 06:41:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions EXPERIENTIALLEARNINGIN SOCIOLOGY 189 Figure2. CurricularBenefitsof DifferentCommunity-Based LearningInitiativesfor Sociology Students CBLType CurricularBenefitfor Students Out-of-Class Activities > > > > Volunteering/ ServiceAdd-Onsa > > > > > > Internship/Practica/Co-op > > > > ServiceLearning observesgroupdynamics/interactions sees newstatusesandrolesactedout experiencesconcreteexamplesof socialphenomena gainsknowledgeandinsightsthrough"realworld"experiences needs gainsawarenessof community encounters diversegroups sees symptomsof problems addressesimmediate concerns in community participates of socialproblems heightensconsciousness illustrates of skills/knowledge practicalapplication fostersdevelopment of newskills/knowledge acquirespractical"hands-on" experience skills appliesdisciplinespecifictheoryandmethodological socialandintellectual developsimportant linkages honesproblemsolvingskills andinstitutional causesof problems > examinesstructural > appliescriticalthinking fromclassand"realworld" > synthesizesinformation > learnslessonsof civicresponsibility > implementsabstractconcepts citizeneducation/civic Service-Learning Advocacy > literacy enharices skills > develops/hones leadership > actsas anagentof socialchange > gainsexperiential knowledgeof powerrelations enhancespoliticalsocialization > > becomesempowered > enhancesmoralcharacter development skills > gainscollaborative > adoptsan interdisciplinary approach "aThese twoCBLoptionswerecombinedsincetheydifferonlyin thecurricular creditreceived. > > benefits for students, a faculty member might initiate a program of service-learning advocacy. Such pedagogy could include students working at a battered-women'sshelter as court companions. In addition to the service provided, as with service learning in general, students would be encouraged to critically examine the socio-historical context in which violence against women occurs, and the effectiveness of institutional responses. Students might also evaluate the adequacy of facilities available to abused women, and based upon their findings, begin a fund-raising and media campaign de- signed to increase public awareness and raise needed revenues. It is in this final CBL initiative that students act collaboratively as agents of social change, and in which they are most likely to develop leadership skills, political awareness, and civic literacy. CONCLUSION In different contexts, each of us has struggled with the promise and difficulties of integrating CBL options into our teaching. We have critically reflected on our own This content downloaded from 137.205.95.22 on Wed, 10 Apr 2013 06:41:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 190 TEACHINGSOCIOLOGY praxis and on the collective praxis reflected in the recent service-learningliterature.The hierarchy of community-based learning options outlined in Figure 1 grew out of that process as an effort to conceptualize an empirical basis for differentiating between various CBL endeavors. Such differentiation is important as CBL and service learning become more popular. Faculty members approaching such endeavors for the first time, program evaluators, and researchers seeking to assess their effectiveness will all need to differentiateamong forms of CBL in order to clearly understandthe benefits and limitationsof each type. Careful delineation also clarifies the ways lower level CBL options can provide the base of skills and experience needed to pursue higher level CBL options. Such an understandingis important for sequencing curricular offerings. Programs or departmentsseeking to implement CBL and service learning into their curricula may want to integrate lower level CBL options, for example, out-of-class activities and service add-ons, into lower division courses with internships and integrate service learning into upper division courses. Students in such programs would take a series of courses culminating in servicelearning advocacy as part of a capstone experience. In identifying and describing a hierarchical typology of community-based learning options that culminateswith service-learning advocacy, we want to avoid two common pitfalls: the reification of the typology itself, and the mirage that definitional consensus i's a prerequisite of improved praxis. Typologies like the one developed here are useful deductive propositions that enable investigators and practitioners alike to make provisional sense out of the complex social realities representedby the increasing popularity of CBL in higher education. The typology developed here is heuristic, intendedto stimulate discussion and reflection and in turn facilitate improved praxis. Yet, typologies of this sort often become counterproductive. If pushed beyond their heuristic limits, they foster definitionaldisputes about what fits which type and to what extent. Such "boundary maintenance" efforts lead to ever more fine-grained description, but not to ever-improving praxis. Thus, any inclination that common definitions must be adopted as a necessary condition for improved CBL practices should be resisted. Conceptual refinement comes through praxis-the critical reflection upon past struggles that orients subsequent rounds of practice upon which CBL practitionerswill later reflect. Indeed, we make the road by walking (Horton and Freire 1990). REFERENCES Melissa.2000. "TheWashington Aberle-Grasse, Yearof EasternMennoniteUniStudy-Service versity: Reflectionson 23 Years of Service Learning."AmericanBehavioralScientist43 (5):848-57. Bellah,Robert,RichardMadison,WilliamSullivan, Ann Swidler,and StevenTiptoe. 1985. and ComHabitsof the Heart:Individualism mitmentin AmericanLife. New York:Harper Row. Blyth,Dale A., RebeccaSaito,andTomBerkas. 1997. "A Quantitative Studyof the Impactof Service LearningPrograms."Pp. 39-56 in ServiceLearning:Applications from the Research, editedby Alan Waterman.Mahwah, NJ:LawrenceErlbaumAssociatesPublishers. Boss, J. 1994. "TheEffectof CommunityService Workon the MoralDevelopmentof ColJournalof MoralEducalege EthicsStudents." tion23:183-98. Boyer,Ernest.1983. "HighSchool:A Reporton SecondaryEducationin America."New York: HarperRow. . 1990. ScholarshipReconsidered: _ Priorities of the Professorate.Princeton,NJ: The of CarnegieFoundationfor the Advancement Teaching. . 1994. "Creating the New AmericanEdu_ cation."Chronicleof HigherEducationMarch 9, p. A48. Brandon,RichardN. and Michael S. Knapp. 1995. "A Service LearningCurriculumfor SerFaculty."MichiganJournalof Community viceLearning2:112-22. . 1999. "Interprofessional Educationand _ ProfessionalPreparaTraining:Transforming tionto Transform HumanServices."American BehavioralScientist45(5):876-93. This content downloaded from 137.205.95.22 on Wed, 10 Apr 2013 06:41:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions EXPERIENTIALLEARNINGIN SOCIOLOGY Bringle, Robert and J. Hatcher. 1996. ServiceLearningin HigherEd"Implementing ucation."Journalof HigherEducation67(2): 221-239. Bringle,Robert,RichardGames,CathyLudlum, RobertOsgood,and RandallOsborne.2000. "FacultyFellows Program:EnhancingIntegrated Professional Development through CommunityService." AmericanBehavioral Scientist45(3):882-94. Brooks,J. Michael. 1997. "Sociologyand VirtualTeachingandLearning." TeachingSociology 27:1-14. Burns,LeonardT. 1998."MakeSureit's Service LearningNot Just CommunityService."The Education Digest64(2):38-41. Calabrese,R. L. and H. Schumer.1986. "The Effects of Service Activities on Adolescent Adolescence21:675-87. Alienation." Chapin,June R. 1998. "Is Service Learninga GoodIdea?Datafromthe NationalLongitudinal Studyof 1988."Social Studies89(5):20512. Conrad,D. andD. Hedin.1982."TheImpactof on AdolescentDevelopEducation Experiential ment."Childand YouthServices4(3/4):57-76. Corwin,Patricia.1996. "Usingthe Community as a Classroom for Large Introductory Classes."TeachingSociology24:310-15. Delve, C.I., S.D. Mintz, and G.M. Stewart. ValueDevelopmentthrough 1990. "Promoting CommunityService:A Design." New Directionsfor StudentServices50:7-9. Dewey, John. 1916. Democracyand Education. NewYork:Macmillan. . 1937. Educationand Social Changein the LaterWorksof JohnDewey, Vol. 2. Carbondale,IL: SouthernIllinoisUniversityPress. . 1938. Experience and Education. New York:CollierBooks. Easterling,Debbie and FredericRudell. 1997. "Rationale,Benefitsand Methodsof Service Learningin MarketingEducation."Journalof Education for Business73(1):58-61. Edgerton,Russell,1994. "TheEngagedCampus: Organizingto ServeSociety'sNeeds."ACHE Bulletin47:3-4. Edwards,Bob and Michael W. Foley. 1997. "SocialCapitaland the PoliticalEconomyof our Discontent."AmericanBehavioralScientist40(5):668-77. Edwards, Bob and Sam Marullo. 1999. "Universitiesin TroubledTimes:Institutional Responses."AmericanBehavioral Scientist 42(5):748-59. Enos, SandraandMarieTroppe.1996. "Service 191 Learningin the Curriculum."Pp. 156-81 in ServiceLearningin HigherEducation,edited by Barbara Jacoby.SanFrancisco,CA:JosseyBass. SocialInEverett,Kevin. 1998. "Understanding equalitythroughServiceLearning."Teaching Sociology26:299-309. Fertman,C.I. 1994. ServiceLearningfor All Students.Bloomington,IN: Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation. Finn, ChesterE. and Gregg Vanourek.1995. "CharityBegins at School." Commentary 100(4):46-49. Franklin,B.A. 1995. "In Our NationalLoss of the PoliticalPartiesareBecoming Community, a WastelandToo." TheWashington Spectator, February15, pp. 1-3. Freire,Paulo.1970.Pedagogyof the Oppressed. New York:Continuum. . 1973. Educationfor CriticalConsciousness. New York:Siberia. CrossCurrents ? 1974."Conscientization." 24(1):23-31. _ . 1985. The Politics of Education. New York:BerginandGarvey. Gardner,Bonnie. 1997. "TheControversyover NEAToday16(2):17-18. ServiceLearning." Gaventa,John.1993. "ThePowerful,the Powerless, andthe Experts:KnowledgeStrugglesin an Information Age." Pp. 21-40 in Voicesof Change,editedby PeterPark,MaryBrydonMiller,BuddHall, andTed Jackson.Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education Press. Gere, Anne Rugglesand JenniferSinor. 1997. "ComposingService Learning."The Writing Winter:53-63. Instructor Giles, Dwight, E. Porter Honnet, and S. Migliori, eds. 1991. ResearchAgendafor ServiceandLearningin the 1990s. Combining Raleigh,NC: NationalSocietyfor Experiential Educations. Goodlad,J. 1984."APlaceCalledSchool."New York:McGraw-Hill. Gose, Ben. 1997. "ManyCollegesMovetoward LinkingCoursesup with Volunteerism."The Chronicleof Higher Education44(12):A45A46. Greco,N. 1992. "CriticalLiteracyandCommunity Service: Reading and Writing in the World."EnglishJournal81:83;85. Gronski, Robert and Kenneth Pigg. 2000. "Universityand CommunityCollaboration." AmericanBehavioralScientist43(5):781-93. Groome,ThomasH. 1980. ChristianReligious Education:SharingOurStoryand Vision.San This content downloaded from 137.205.95.22 on Wed, 10 Apr 2013 06:41:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 192 TEACHINGSOCIOLOGY Francisco,CA:Harper& Row. Hinck,ShellySchaeferandMaryEllenBrandell. 2000. "TheRelationship betweenInstitutional SupportandCampusAcceptanceof Academic ServiceLearning."AmericanBehavioralScientist43(5):868-81. RobertJ. and LarryLovellHironimus-Wendt, ServiceLearningin Troy. 1999. "Grounding Social Theory."TeachingSociology27:36072. Horton,MylesandPauloFreire.1990. WeMake on EducatheRoadby Walking:Conversations tion and Social Change. Philadelphia,PA: TempleUniversityPress. Howard,J.P.F. 1998. "AcademicServiceLearnPedagogy."Pp. 21ing: A Counternormative 29 in AcademicServiceLearning:A Pedagogy of Action and Reflection, edited by R.A. Rhoadsand J.P.F. Howard.San Francisco, CA:Jossey-Bass. Hutchings, P. and A. Wutzdorff. 1988. Learningacrossthe Curriculum: "Experiential Assumptionsand Principles." Pp. 5-19 in KnowingandDoing:LearningthroughExperience, editedby P. Hutchingsand A. Wutzdorff. SanFrancisco,CA:Jossey-Bass. Jacoby,Barbara.1994. "BringCommunityService intotheClassroom."Chronicle for Higher Education,August15, p. B2. Jacoby,Barbara,ed. 1996. ServiceLearningin HigherEducation.SanFrancisco,CA: JosseyBass. James, William. 1907. Pragmatisim,a New Namefor Some Old Waysof Thinking.New York:Longman's,Green,andCo. Kahne,Josephand Joel Westheimer.1996. "In the Serviceof What?The Politicsof Service PhiDeltaKappa77(9):592-603. Learning." Keith,Novella.1994. "School-Based Community Service:AnswersandSomeQuestions."Journal of Adolescence17:311-320. Kendall,Susan. 1990. CombiningServiceand and Learning:A ResourceBookfor Community PublicService,Vol. 1. Raleigh,NC: National Education. Societyfor Experiential J. 2000. "MoralLanguage Koliba,Christopher AmericanBeand Networksof Engagement." havioralScientist43(5):825-38. Koulish, Robert. 1998. "CitizenshipService Learning:BecomingCitizensby AssistingImmigrants." Political Science and Politics 31(3):562-68. Lena, Hugh. 1995. "How Can SociologyContributeto IntegratingService Learninginto AcademicCurricula."TheAmericanSociologist 26:107-17. Marullo, Sam. 1996. "The Service Learning An Academic Movementin HigherEducation: Times." to Troubled Sociological Response 33:117-37. Imagination . 1998. "Bringing Home Diversity: A Service-Learning Approachto TeachingRace and Ethnic Relations." TeachingSociology 26:259-75. Marullo,SamandBobEdwards.2000a."Editors AmericanBehavioralScientist Introduction." 43(5):746-55. _ . 2000b. "From Charity to Justice: The CollaboraPotentialof University-Community tion for SocialChange."AmericanBehavioral Scientist43(5):895-912. McCarthy,Mark. 1996. "One-Timeand ShortTermServiceLearningExperiences." Pp. 11334 in ServiceLearningin HigherEducation, editedby BarbaraJacoby.SanFrancisco,CA: Jossey-Bass. Merrifield,Juliet. 1993. "PuttingScientistsin Researchin EnvirontheirPlace:Participatory Health."Pp. 65-84 in mentalandOccupational Voicesof Change,editedby PeterPark,Mary BuddHall, and Ted Jackson. Brydon-Miller, forStudiesin EducaToronto:OntarioInstitute tionPress. Miller, Jerry. 1994. "LinkingTraditionaland Service LearningCourse:Outcome Evaluations Utilizing Two Pedagogically Distinct Models."MichiganJournalof Community ServiceLearning1:29-36. Mintz, Suzanneand Garry W. Hesser. 1996. of GoodPracticein ServiceLearn"Principles in ServiceLearningin Higher 26-51 ing." Pp. Education,edited by BarbaraJacoby. San Francisco,CA: Jossey-Bass. J. Scott. 1998. "Effectsof a ComMyers-Lipton, prehensiveService LearningProgramon College Students'Civic Responsibility." Teaching Sociology25:243-58. Nationaland CommunityServiceAct of 1990. Pub.L. No. 101-610. Newmann,Fred. 1975. Educationfor Citizen Action:Challenges for SecondaryCurriculum. Berkeley,CA: McCutchan. Palmer, Parker. 1983. To Know as We Are Known:A Spirituality of Education.SanFrancisco, CA: Harper& Row. RePark, Peter. 1993. "Whatis Participatory search?A Theoretical andMethodological Perspective."Pp. 1-20in Voicesof Change,edited BuddHall by PeterPark,MaryBrydon-Miller, andTedJackson.Toronto:OntarioInstitutefor Studiesin Education Press. Rachel.1996."Connecting Service Parker-Gwin, This content downloaded from 137.205.95.22 on Wed, 10 Apr 2013 06:41:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions EXPERIENTIALLEARNINGIN SOCIOLOGY to Learning:How Studentsand Communities Matter."TeachingSociology24:97-101. Racheland J. Beth Mabry.1998. Parker-Gwin, "ServiceLearningas PedagogyandCivicEducation:ComparingOutcomesof Three Models." TeachingSociology26:276-91. Parilla,Peter F. and GarryW. Hesser, 1998, and the SociologicalPerspective: "Internships ApplyingPrinciplesof Experiential Learning." TeachingSociology26:310-29. Perreault,Gerri E. 1997. "CitizenLeader:A CommunityService Optionfor College Students."NASPAJournal34(2):147-55. Pestello, FrancesG., Dan E. Miller, Stanley Saxton, and Patrick G. Donnelly. 1996. and the Practiceof Sociology." "Community TeachingSociology24:148-56. Plater,W.M. 1995."FutureWork:FacultyTime in the21"'Century."ChangeMay-June:22-23. Porter,JudithR. and Lisa B. Schwartz.1993. Service-BasedLearning:An In"Experiential tegratedHIV/AIDSEducationModelfor College Campuses."TeachingSociology21:40915. RandEducation.1999. "Combining Serviceand Learningin HigherEducation:SummaryReServiceLearningandHigher port."Combining Education:Evaluationof the Learnand Serve America,HigherEducationProgram.Washington,DC. Roschelle,Anne, JenniferTurpin, and Robert Elias.2000. "WhoLearnsfromServiceLearning?" AmericanBehavioral Scientist43(5): 839-47. Rothman,M., E. Anderson,and J. Schaefer. 1998. Servicematters:EngagingHigherEducationin the Renewalof America'sCommunities and American'sDemocracy.Providence, RI:CampusCompact. Service Rubin,Sharon.1996. "Institutionalizing Learning."Pp. 297-316in ServiceLearningin HigherEducation,editedby BarbaraJacoby. SanFrancisco,CA:Jossey-Bass. Rudell, Frederic. 1996. "StudentsAlso Reap Benefitsfor Social Work."MarketingNews 30(17):12-13. Social Rundblad,Georganne.1998. "Addressing Problems,Focusingon Solutions:The ComProject."TeachingSociolmunityExploration ogy26:330-40. Saltmarsh,John. 1996. "Educationfor Critical JohnDewey'sContribution to the Citizenship: Pedagogyof CommunityService Learning." ServiceLearnMichiganJournalof Community ing 3:13-21. Sax, LindaandAlexanderW. Astin. 1997. "The 193 Benefitsof Service:EvidencefromUndergraduates."TheEducational Record78(3/4):25-32. Scarce, Rik. 1997. "FieldTrips as Short-Term ExperientialEducation."TeachingSociology 25:219-26. Scheuerman,Cesie. 1996. "OngoingCurricular Service Learning."Pp. 135-55 in Service Learningin HigherEducation,editedby BarbaraJacoby.SanFrancisco,CA:Jossey-Bass. Shumer, Robert. 1990. "Community-Based Learning:An Evaluationof a Drop-OutPrevention Program."Report submittedto the Cityof Los AngelesCommunity Development Department.Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Field StudiesDevelopment. _ _ . 1994. "Community-BasedLearning: Hu- manizingEducation."Journalof Adolescence 17:357-67. . 1997. "Learning From Qualitative Re- search."Pp. 27-38 in ServiceLearning:Applicationsfrom the Research,editedby Alan S. Waterman.Mahwah,NJ: LawrenceErlbaum AssociatesPublishers. Shumer,Robertand BradBelbas. 1996. "What We KnowaboutServiceLearning."Education and UrbanSociety28(2):208-23. Shumer,Robertand CharlesCook. 1999. "The Statusof ServiceLearningin theUnitedStates: Some Facts and Figures."NationalService LearningClearinghouse.RetrievedJune 17, 2000 (http://www.nicls.coled.umn.edu/res/ mono/status.html). Tyack,DavidandLarryCuban.1995. Tinkering toward Utopia:A Centuryof Public School Reform.Cambridge,MA: HarvardUniversity Press. Wade, RahimaC. 1997. "CommunityService Learningand the Social StudiesCurriculum: Challengesto EffectivePractice."SocialStudies 88(5):197-202. Wade, RahimaC. and David W. Saxe. 1996. "CommunityService Learningin the Social Studies:HistoricalRoots, EmpiricalEvidence and CriticalIssues."Theoryand Researchin SocialEducation24:331-59. Wallace, John. 2000. "A PopularEducation Modelfor Collegein Community." American BehavioralScientists43:756-66. Ward,Kelly, 1996. "'ServiceLearning'Reflections on Institutional Commitment." Michigan Journalof ServiceLearning3:55-65. Ward, Kelly and Lisa Wolf-Wendel. 2000. "Community-CenteredService Learning: MovingfromDoingfor to Doingwith."AmericanBehavioralScientist43(5):767-81. Waterman,AlanS., ed. 1997. ServiceLearning: This content downloaded from 137.205.95.22 on Wed, 10 Apr 2013 06:41:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 194 TEACHINGSOCIOLOGY Applicationsfrom the Research. Mahwah, NJ: LawrenceErlbaumAssociates Publishers. Zlotkowski, Edward. 1996. "Opportunity for All: Linking Service-Learning and Business Education."Journal of Business Ethics 1:5-19. of the textbook UnderstandingSocial Problems (Wadsworth). Bob Edwardsis graduatedirectorof sociologyat EastCarolinaUniversity.His researchinterestscenter aroundsocial movementsand advocacyorganizations Linda A. Mooney is an associate professorof andtheirrelationship to politicalparticipation andsocial sociologyat East CarolinaUniversityin Greenville, change.He is co-editorwith Sam Marulloof a twoNC. Herresearchandteachingareasincludesociology issueseriesof theAmericanBehavioralScientist:"The of law, criminology,socialproblems,andmassmedia. Service LearningMovement:Responseto Troubled Shehaspublished articlesin SocialForces,Sociological Times in HigherEducation" 43(5):741-912(February and 2000); and "Universitiesin TroubledTimes: InstituInquiry,SexRoles,andTheSociologicalQuarterly, on thethirdedition tionalResponses" is presentlyworkingwithco-authors 42(5):743-901(February1999). This content downloaded from 137.205.95.22 on Wed, 10 Apr 2013 06:41:15 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions