By Anne-Pauline van der A Becoming Annot: Identity Through Clown

advertisement

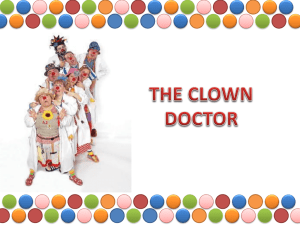

Platform, Vol. 6, No. 2, Representing the Human, Summer 2012 Becoming Annot: Identity Through Clown By Anne-Pauline van der A Abstract This article tracks the performative creation and evolution of a clown persona, ‘Annot’, that I developed as part of my academic research into the construction of clown personae by their performers. To capture her I employed the medium of performance photography. Concentrating on the actions performed, my clown arose from impulses and responses to gestures. Following the definition of performativity, identity came later, through action. However, as any construction of the body is also a construction of the individual as embodied, my investigation of the performative construction of the figure of the clown resulted at the same time in a highly personal and therefore new and original performance. Since clowning awakens hidden aspects of the individuals involved, it allows for the integration of form and emotion as expressed by the clown performer. This article argues that it is precisely in the performance of clown that identity is revealed as an authentic expression of human embodiment. The clown is ubiquitous. The clown is of all times and of all places. ‘Clown’ can describe a range of figures, behaviours and situations. The very diversity of clown makes a comprehensive definition difficult; but the persistent, recognizable notion of clown suggests that there must be some essential performative quality worth exploring. My own previous research into clown performances sparked my interest in the way in which a performer constructs and develops his clown persona.* I therefore decided to investigate how the various contemporary approaches to clown might inform such a process. In this article I will track the performative creation and evolution of my own clown persona, Annot. Through the creative process of becoming Annot and through my own performance * See van der A, ‘Performing Charlot/Hulot’. Both Charlot and Hulot can be seen as the inspiration for Annot’s name, accordingly pronounced ‘ah-NO’. 86 Becoming Annot practices in both private and public space, I explored the processes of ‘becoming clown’ and examined the extent to which this process negotiates embodiment. My practical research on clown and on the relationship of the clown persona to the self contextualised my theoretical approach and contributed to the existing theoretical material on clowning. This article argues that precisely the construction of a clown persona and his subsequent performance permit not only an expression of the personal through clown – as his identity is revealed as a truthful and authentic expression of the performer’s self – but also allow for the provocation that, to an extent, the clown persona can be identified as a person existing in his own right. Drawing on my own basic clown training, I will examine the training of the modern clown performer and discuss the conceptions and techniques he acquires. I will indicate how the performer may apply these in the development of his own clown and in his interaction, or even confrontation, with the audience. In addition I will focus on the intrinsic paradox of the clown, whose incongruent performance not merely provides entertainment, but who through his performance seeks to encourage contemplation and reflection, even subversion. This will be juxtaposed with the creation of my own clown persona, Annot, and her first experiences in the outside world. To document the actions that Annot performed and the reactions she effectuated through her performances I turn to performance photography. The art form of performance photography is both a representative of the artistic practice and an inherent part of the creative act: the act of documenting an event as a performance is what constitutes it as such, because its liveness exists not as a prior condition, but as a result of its mediatisation (Auslander 5; cf. Taylor 35). To quote multimedia artist and writer Coco Fusco, performance photography forms ‘the only means of sustaining the life of [the] performance’ (62). The photographic record of Annot’s performances accordingly enabled me to reflect on the figure and function of the clown, as this visual documentation showed me the performing image of this clown persona as well as her perception by the audience. 87 Platform, Vol. 6, No. 2, Representing the Human, Summer 2012 Fig.1 Annot (2011). Courtesy of Anne-Pauline van der A. 88 Becoming Annot Creative clown training: how to develop an authentic persona The initial manifestation of Annot mainly derives from a six-week placement that I undertook in the spring of 2011 at Circomedia, Centre for Contemporary Circus and Physical Performance in Bristol,* where I attended classes in clowning and obtained varied training and creative learning through observation and participation in an area of performance practice that was largely new to me. My introduction to the world of clown culminated in a three-day masterclass by mask teacher Steve Jarand, during which I was encouraged to let go of my ‘imposed I-persona’ by way of the Trance Mask-method. It seems significant that by wearing a mask I allowed myself the freedom to drop the ‘mask’ that I felt society had imposed on me in recent years. I had to undergo this personal development before my clown persona was disclosed to me and could manifest herself; concentrating on the actions that I performed, allowing for the ‘development of the active side of consciousness and sensations in the process of human becoming’ (Simonsen, 3), my clown arose from my own personal impulses and responses to gestures. Circomedia’s educational philosophy is based on the theories of French actor, mime and clown master Jacques Lecoq (1921-1999), founder of the famous physical theatre and clown school L’École Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq in Paris. The idea that each individual has one or more clowns within himself lies at the centre of Lecoq’s approach to clowning. According to Lecoq, his students were drawn to his conception of clown because its then novel approach permitted liberation from socially assigned conditions (cf. Murray 62). Clowning forms a domain of possibilities for a performer as basic modern clown training includes attempts to reveal ‘the person underneath, stripped bare for all to see’ (Lecoq 154). This suggests that the clown persona cannot exist apart from the person performing him. The clown performer creates a character identity which, although perhaps not entirely that of the performer himself, is nevertheless tailored to his needs for self-expression. Clowning allows for the integration of * Circomedia, the internationally-respected centre of excellence for circus and theatre training, founded in 1994 by physical theatre expert and clown Bim Mason and choreographer and performer Helen Crocker, was set up as a continuation of Fool Time, the first circus school in Britain, founded in 1986. See also Gartside 13. 89 Platform, Vol. 6, No. 2, Representing the Human, Summer 2012 form and emotion as expressed by the clown performer. Following the definition of performativity, identity comes later, through action (Mazzone-Clementi 61). As such, the modern clown performer frequently chooses to adopt a ‘performance persona’ based on the off-stage ‘self ’, on which he draws as a foundation to develop his material beyond the constraints of realist- or illusionistic-led scenes (cf. Bailes xvii). This also means that the clown performer does not convey feelings and ideas originally voiced by someone else: When a clown performs, the audience sees the ideas and attitude of that individual conveyed by an adopted persona that has developed out of the individual’s personality and which could never be adopted and lived in the same way by anyone else. The clown is not an interpreter. In his or her performance the view of and reaction to the world is the same for the creation […] as for the performer. (Peacock 14) The techniques included in modern theatre training require considerable physical effort and are therefore sometimes defined as imprisoning processes of the body. Yet the paradox which lies at the heart of these techniques is that the performer, by mastering them, gains the freedom and spontaneity that are so essential for an authentic clown persona. A combination of the body techniques of clowning and (classes in) physical theatre therefore allows the clown performer to construct unique clown characteristics according to his own personal style. These clown conceptions emphasize the single, sheer creator in clown (cf. Little 55-56). The main emphasis of clown work thus amounts to (physical) self-discovery: ‘clowning awakens hidden aspects of all individuals involved’ (Peacock 154). By stimulating transparency towards the world, clowning also invites the performer to reveal his shortcomings. This corresponds with the philosophy of Circomedia’s Bim Mason: I always see teaching clowning, learning clowning, as a means to an end: it is a way for people to learn to laugh at themselves, to base it on who they are, their real personalities and their real bodies. 90 Becoming Annot What I try to do is get them easy with their imperfections. (Lidington) As such, the role of clown also involves an exhibition of some incongruity, vulnerability, weakness or failure. As actress and clown Angela De Castro suggests: ‘clowns celebrate imperfection and that makes it more real’ (qtd. in Peacock 95). To become a clown one must be distorted from expectation in appearance or conduct (Klapp 158-159), ultimately resulting in a highly personal and therefore new and original performance: the clown clowns to express his personal observations about life and humanity. Meet Annot: the creation of my own clown persona This conception of clown as something highly personal and as dependent upon experience at a personal level is something I came across in my own performance practice as well. I started from personal exploration through performing clown play, but hardly worked according to any predetermined, academic design. Instead I sometimes found myself less in control of my research than I had envisaged: occasionally serendipity seemed to take over, prompting me to allow for the discovery of what might appear. I realised that much of the creative process seemed to happen subconsciously, such as when my clown persona introduced herself to me during my training; I suddenly ‘saw’ the image of a female clown, as clearly as if she had just entered the room. The name ‘Annot’ came to mind almost simultaneously. Fig.2 ‘An Emerging Persona’ (2011). Courtesy of Anne-Pauline van der A. 91 Platform, Vol. 6, No. 2, Representing the Human, Summer 2012 Gradually the different forms of physicality, motion, physical accents and postures of Annot started to emerge. Putting together the appropriate costume for my clown did not primarily include conscious decisions either, but happened rather more arbitrarily, adapting garments that I could find in various wardrobes. Annot’s short, white dress and black stockings underline her childishness as well as her gender, while the blue vintage jacket on top more generally emphasizes the figure’s angular shoulders. The other main component of Annot’s costume is an oversized, red duffle coat, which seems particularly appropriate since the colour red appears to be iconic to clown. Upon her head Annot often wears a bowler hat – another iconic clown attribute – while the glasses that I, as an individual, would otherwise wear are shadowed in the black circles around her eyes. I chose plump shoes to fit in with the rest of Annot’s costume so as to accentuate my somewhat clumsy gait as well as my feet: feet that in total relaxation point almost perfectly (heels together) to the right and to the left. Fig.3 ‘Out and About in Public Space’ (2011). Courtesy of Anne-Pauline van der A. 92 Becoming Annot The effect of applying these characteristics is that the body becomes the ‘stage’ for the eccentricity of the clown: transgressing its own boundaries, the body plays up its own exaggeration (cf. Lachmann 146). That is, in the way that the clown presents himself by altering his physical appearance, the figure reinforces any bodily defects he might have by means of his choice of costume. As the construction of the body determines the construction of the individual as embodied, this element of clown has not so much to do with putting on a show, but forms a part of the clown that ‘is like a skin’ (Peacock 38). Similarly, Annot’s big, brightly coloured duffle coat visually externalizes a specific bodily experience, as it is appropriate to the fact that I often feel cold. This coheres with a more postmodern performance style in which the performer draws attention to himself as an individual, not as a character (Peacock 105). It precisely ‘blurs the boundaries between private and performative personae and thus displays and deconstructs the performative self’ (Groot Nibbelink 306). The actions and gestures that I perform as Annot are often integrated into the everyday, blending personal identity and performance. With this in mind, I intentionally rejected the red clown’s nose, as it locates the clown too emphatically within a frame of exaggeration and overt humour; the attribute can form a barrier for the performance as it might lead to a certain expectancy on the part of the audience for the performer to ‘do something funny!’. However, the transgression from the norm will be obvious enough to mark the clown as different, signifying that the clown is a clown (cf. Peacock 15). This peculiarity of the clown figure was illustrated during the production of my performance photography, when ‘Annot’ went for coffee at a local café; although my costumed appearance and the presence of a person with a camera (even taking pictures inside the premises) occurred within an obvious performance frame, we were ignored for a long time before we were somewhat reluctantly served. Evidently, what may not even cause someone to raise an eyebrow in one context, may arouse rather more intense reactions in another (cf. Miller 318). And the incident suits the mode: the clown’s act is continuous and involves ‘the never-ending and precarious dramatizing of what happens to such a [figure] when thrust into the realities of life itself’ (Tyler 83). For there is always something of the ‘other’ about the figure of the clown, in particular an ‘otherness’ in his attitude to life as expressed through his performance (Peacock 2). 93 Platform, Vol. 6, No. 2, Representing the Human, Summer 2012 Fig.4 Waiting to be served (2011). Courtesy of Anne-Pauline van der A. An identity of contrasts Note, however, that the clown sees nothing peculiar in himself; the clown simply is (cf. Larner 114): ‘The reactions of […] the audience are the strange thing. He is normal’ (Mazzone-Clementi 63). Nevertheless the clown, distinguishing himself from others by deviating both in appearance and in physicality, is an outsider from human society. This position, however, grants him the freedom to expresses his observations on humanity and on contemporary life by commenting on the interaction between individuals and the society in which they live. By taking what is socially presumed as ‘normal’ and ‘natural’ out of its usual context, the clown explores the incongruity and inherent absurdity of his own clowning as he confronts his audience with an alternative perspective: ‘a way of 94 Becoming Annot looking at the world that is different, unexpected, and perhaps even disturbing’ (Swortzell 2). The result of this kind of deviant behaviour can be ambiguous, even wry. As adopted by contemporary artists, the previously comical role of clown has evolved into a more reflective performance with a more cynical figure (Fisher 30). Donald McManus even suggests that the 20th century was the century in which the character of the clown ceased to be comic. The clown has become the means through which the more tragic, modern impulse of the world can be expressed as an insight, a question, or a commentary that is rather more confrontational than it is entertaining, causing the audience to laugh in spite of themselves.* Fig.5 ‘An identity of contrasts’ (2011). Courtesy of Anne-Pauline van der A. * As Jan Jan Kott noted early in the 1960s in his essay ‘King Lear or Endgame’: ‘When established values have been overthrown, and there is no appeal to God, Nature, or History, from the tortures by the cruel world, the clown becomes the central figure’ (qtd. in Schechter 100). According to Jan Kott, in King Lear Shakespeare moves his clown character in a new direction; Lear’s Fool’s stands in relation to his master as an alter ego. As such the figure is anachronistically like the modern clown, not simply deployed to make his audiences laugh, but ideally attuned to reveal the pain of existence, or ‘what it is to be human and to be flawed’ (Peacock 93). 95 Platform, Vol. 6, No. 2, Representing the Human, Summer 2012 Accordingly, clown-play can include tension, disengagement or alienation, even anxiety and hysterics, and can involve physical and emotional risks to the performer’s self (Hyers 6; Callery 64; Peacock 12; cf. Schechner 82). Indeed, Schechner has remarked that the etymology of the English word ‘play’ includes allusions to risk and danger, as the oldest meaning of the verb is ‘to vouch or stand guarantee for, to take a risk, to expose oneself to danger for someone or something’ (81; cf. 80). Thus the etymology of the word ‘play’, so inextricably linked to clown, corroborates the notion that the performance of clown is often situated ‘on the edge of self-destruction’ (Manvell 27). As Kevin Kern puts it: ‘Breakdowns, missteps and screw-ups are life forces that flow through clown veins’ (195). These forms of failure and disaster are not necessarily always accidental or improvised, and therefore not necessarily unique or irreproducible. They may occur in scripted but also in unscripted acts (Bailes 5), as happened to me when I suffered a minor injury during the creative process of my performance photography. This was not intended or preconceived, but significant in connection to the awkwardness that is a defining characteristic of the clown figure in general, and of Annot specifically. Fig.7 and 8. ‘Unscripted acts’ (2011). Courtesy of Anne-Pauline van der A. During the process of Annot’s creation, the powerful balance of vulnerabilities and strengths that are so intrinsically linked with the clown figure required me to work out parts of myself and to deal with certain issues, uncertainties, painful aspects and fears. In fact, finding that balance was particularly challenging in my case, as I was born significantly prematurely and spent several months in an intensive care incubator that regulated my breathing, my medication, my nutrition and my body temperature. 96 Becoming Annot This condition had far-reaching consequences, in that I suffered severe brain damage during the first hours of my life, which caused permanent injuries to my vestibular system (balance) and adversely affected the coordination of my limbs; in my early childhood it was a major challenge for me to learn to walk properly, and even today I cannot ride a bicycle without falling over. Simpler still, it took me almost ten years before I could put on my socks by myself. During my later childhood I was often ridiculed by people around me – children as well as adults – because of these limitations resulting from my premature birth. The traumas of my preterm suffering, as well as the strengths demanded of me to overcome them, also constitute my personal history in performative terms: the continual medical procedures I was subjected to in the incubator and the actions I thus (forcibly) ‘performed’ played a determinative role in my becoming and shaped me into the person I am now. Accordingly, the vulnerabilities of my early self-emotional as well as physical, as reflected in the actual scarring on my body-have also shaped my clown persona, Annot. During the process of becoming Annot, I realised that her identity is at least partly based on the activities I cannot perform as a result of the damages sustained by my premature birth. But while ‘cannot’ limits me, I realise that there is a lot that I can do, which underscores the suitability of the name ‘Annot’, as opposed to the suppressive and inhibitory quality of ‘cannot’. Moreover, as the name ‘Annot’ resembles my own given name, using it allowed me to remain close to myself. Fig.9 and 10. ‘Performing the incubator’ (2011) and ‘In the incubator’ (1985). Courtesy of Anne-Pauline van der A. 97 Platform, Vol. 6, No. 2, Representing the Human, Summer 2012 Performing the ‘self ’: the humanity of the clown Obviously clown does not mend any (physical) traumas. However, it does allow the clown performer to turn any personal inabilities into his main performative strength. The genius of clowning is not only the overcoming, but also the transforming of the everyday. This is why corporeality is the central axis of clown comedy; the clown’s (in most cases carefully trained) lack of coordination in the physicality of his body mocks society’s controlled norms and rules, and so forms his principal tool for subversion. The technical mastery of the performer in addition to the deployment and even exploitation of the individual strengths and weaknesses of the ‘self ’ constitute a reappropriation, perhaps even a reevaluation of both. As such the discovery of one’s inner clown provides a way of increasing self-awareness and a means of personal development. This allows the clown performer to find alternatives to his ways of behaving in and coping with life. The opportunity to reveal new facets of the self builds confidence and attitude, while ensuring the potential to bring about personal change in that the mode of clown ‘opens up a fruitful, tragicomic ground’ wherein subversion and resistance can be tried out and rehearsed by exposing what others (wish to) keep hidden (Bailes 3; Peacock 156). My research revealed an overlap between theatre and everyday conduct, pointing to the social formation of personality by increasing the visibility on the conceptions of embodiment in human performance. For the clown performer specifically, the clowning mode both stimulates and facilitates his transparency to the world around and the world within. When clowning, the various aspects of the self are not acted out, but revealed: ‘To be a clown is to create and express a total personality’ (Swortzell 3). When the clown performer stands before an audience, he does so in person, not hidden behind an externally created character but revealed in a theatrical version of himself: the clown persona (Peacock 103; cf. James Naremore 11). The performer should, then, be interpreted not as one who is pretending, i.e. performing a character, but as one whose primary concern is being his individual ‘self ’. Because of this, usually a performer assumes his clown persona for life. When the mode requires the clown performer to reveal personal insecurities and vulnerabilities to the audience and to society, such a disclosure of the self may be confrontational. 98 Becoming Annot Yet the clown’s manifold moments of crisis constitute a space for recognition and sympathetic identification for the audience as well, in which the function of clowning to confront the audience with awkward, embarrassing and sometimes even painful situations is particularly resonant: The audience laughs at the clowns [...] but at the same time, they may be laughing with the clowns, internalizing elements of the experience and exploring the parallels between the clowns and themselves. (Peacock 102-103, emphasis in original) Through the clown’s display of human vulnerabilities the audience will recognize themselves as well as the emotions and imperfections of human nature. This is the crucial point about the performance of clown: the audience ‘discovers’ that they all are, in some sense, clowns as well (Delpech-Ramey 140). Fig.11 ‘Human Vulnerability’ (2011). Courtesy of Anne-Pauline van der A. 99 Platform, Vol. 6, No. 2, Representing the Human, Summer 2012 As such the clown constantly deals with what it means to be human; while commenting on the absurdities of life he encourages contemplation with particular emphasis on an existentialist viewpoint (Peacock 26, 14 and 106; cf. Bailes xvi). But because the performance of the clown remains double-edged as both the comic and the tragic occur in the same experience simultaneously, any empathic identification with the figure can quickly pass into an uncomfortable reminder of personal failure when identifying too closely with the clown as victim of a seemingly comic situation (Kris 214). The status of the clown therefore represents a paradox in that the type is both depreciated and valued, rejected as well as embraced (Klapp 161). Indeed, the clown precisely has to be valued and taken seriously, as a situation can only be experienced as ‘tragicomic’ when the object of sympathy retains a minimum of dignity (Hofstadter 302; Delpech-Ramey 136). Fig.12 ‘Performing the self ’ (2011). Courtesy of Anne-Pauline van der A. 100 Becoming Annot With the creation of my own clown persona, Annot, I explored performativity by means of clown. By putting on my costume I deliberately created a situation of performativity which enabled me to emphasize my ‘otherness’. Annot embodies much of what I regard as my personal failures, or what had caused others to exclude me; my performances included a physicality that referred to my bodily limitations due to my premature start in life. However, the specific characteristics of my clown persona worked to turn my weaknesses into a determining strength for me as a performer and as an individual. The creative process towards becoming Annot taught me that laughter is a powerful survival tool. Performing Annot enabled me to put my personal history into perspective, to come to grips with my limitations and to accept them more easily. So Annot is an expression of (parts of ) myself. Simultaneously, Annot can be seen as a person existing in her own right, which in itself poses another paradox. During my research, as well as while I was writing this article, at times I was confronted with the blurring of the two differing identities, of myself and of Annot, of the performer and of the clown. Ultimately, the authenticity of Annot manifested itself in the intriguing feeling that my creative choices seemed to be imposed by my clown persona herself. 101 Platform, Vol. 6, No. 2, Representing the Human, Summer 2012 102 Fig.13 ‘Untitled’ (2011). Courtesy of Anne-Pauline van der A. Becoming Annot Works Cited Auslander, Philip. ‘The Performativity of Performance Documentation’. PAJ 28.3 (2006): 1-10. Bailes, Sara Jane. Performance, Theatre and the Poetics of Failure. New York: Routledge, 2011. Callery, Dymphna. Through the Body: a Practical Guide to Physical Theatre. London: Nick Hern, 2001. Circomedia. Circomedia Centre for Contemporary Circus & Physical Performance: 2011 Prospectus. Bristol: Circomedia, 2011. Fisher, James. ‘Harlequinade: Commedia Dell’Arte on the Early Twentieth-Century British Stage.’ Theatre Journal 41.1 (1989): 30-44. Fusco, Coco. English Is Broken Here: Notes on Cultural Fusion in the Americas. New York: New, 1995. Gartside, Mike. ‘Going Full Circle.’ Venue: Bristol and Bath’s Mag No. 962 18-27 Mar. 2011: 12-15. Groot Nibbelink, Liesbeth. ‘Kaleidoscopic Encounters. The Actor, Character and Spectator in Intermedial Performances’. Theater Und Medien (Theatre and Media): Grundlagen - Analysen – Perspektiven: Eine Bestandsaufnahme. Ed. Henri Schoenmakers, Stefan Bläske, Kay Kirchmann, and Jens Ruchatz. Bielefeld: Transcript, 2008: 303-08. Hofstadter, Albert. ‘The Tragicomic: Concern in Depth’. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 24.2 (1965): 295-302. Hyers, M. Conrad. ‘The Ancient Zen Master as Clown-Figure and Comic Midwife’. Philosophy East and West 20.1 (1970): 3-18. Kern, Kevin P. ‘The Art of Clowning’. Theatre Topics 20.2 (2010): 195. Klapp, Orrin E. ‘The Fool as a Social Type’. The American Journal of Sociology 55.2 (1949): 157-62. Kris, Ernst. ‘Ego Development and the Comic’. Psychoanalytic Explorations in Art. New York: Schocken, 1952. Lachmann, Renate. ‘Bakhtin and Carnival: Culture as Counter- Culture’. Trans. Raoul Eshelman and Marc Davis. Cultural Critique 11 (1988-1989): 115-52. 103 Platform, Vol. 6, No. 2, Representing the Human, Summer 2012 Larner, Daniel. ‘Passions for Justice: Fragmentation and Union in Tragedy, Farce, Comedy, and Tragi-Comedy’. Cardozo Studies in Law and Literature 13.1 (2001): 107-18. Lecoq, Jacques. The Moving Body: Teaching Creative Theatre. Trans. David Bradby. London: Routledge, 2002. Lidington, Tony. Bring on the Clowns. Prod. Mike Greenwood. A Pier Production for BBC Radio 4. 24 Feb. 2011. Little, W. Kenneth. ‘Pitu’s Doubt: Entree Clown Self-Fashioning in the Circus Tradition’. The Drama Review 30.4 (1986): 51-64. Manvell, Roger. Chaplin. Boston: Little and Brown, 1974. Mazzone-Clementi, Carlo. ‘Commedia and the Actor’. The Drama Review 18.1 (1974): 59-64. McManus, Donald. No Kidding! Clowns as Protagonist in Twentieth-Century Theatre. Cranbury, NJ/London/ Ontario: Associated UPs, 2003. Miller, Samuel H. ‘The Clown In Contemporary Art’. Theology Today 24.3 (1967): 318-28. Murray, Simon. Jacques Lecoq. London: Routledge, 2003. Naremore, James. ‘Film and the Performance Frame’. Film Quarterly 38.2 (1984-1985): 8-15. Peacock, Louise. Serious Play: Modern Clown Performance. Bristol: Intellect, 2009. Schechner, Richard. Performance Studies: an Introduction. London: Routledge, 2002. Schechter, Joel. ‘Clowns before Beckett’. Theater 28.2 (1998): 100-02. Simonsen, Kirsten. ‘Bodies, Sensations, Space and Time: The Contribution from Henri Lefebvre’. Geografiska Annaler B, Human Geography 87.1 (2005): 1-14. Swortzell, Lowell. Here Come the Clowns: a Cavalcade of Comedy from Antiquity to the Present. New York: Viking, 1978. Taylor, Diana. The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. London: Duke UP, 2003. Tyler, Parker. Chaplin: Last of the Clowns. New York: Vanguard, 1948. Van der A, Anne-Pauline. ‘Performing Charlot/Hulot: An exploration in scholarship and practice of the figure of the modern clown through the performances of Charlie Chaplin and Jacques Tati’. Diss. University of Warwick and Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2011. 104