Document 13385970

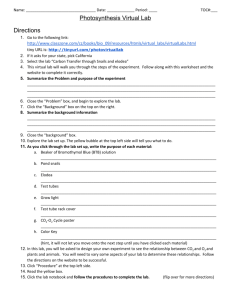

advertisement