INVOLVED SPECTATORSHIP IN ARCHAIC

GREEK ART

GUY HEDREEN

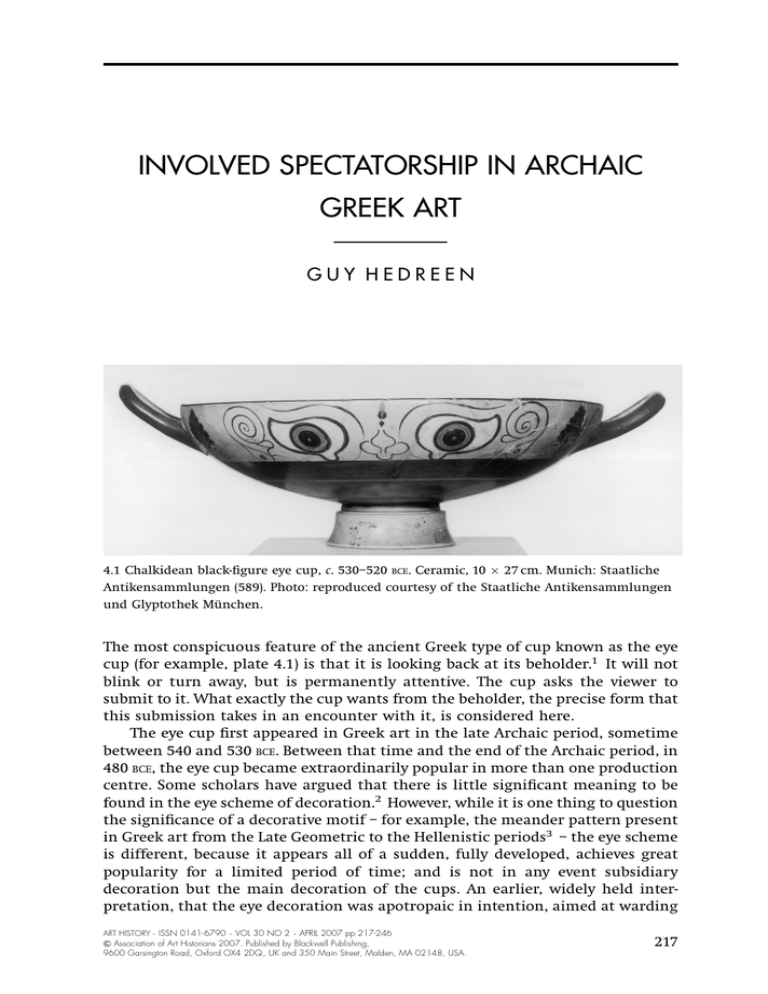

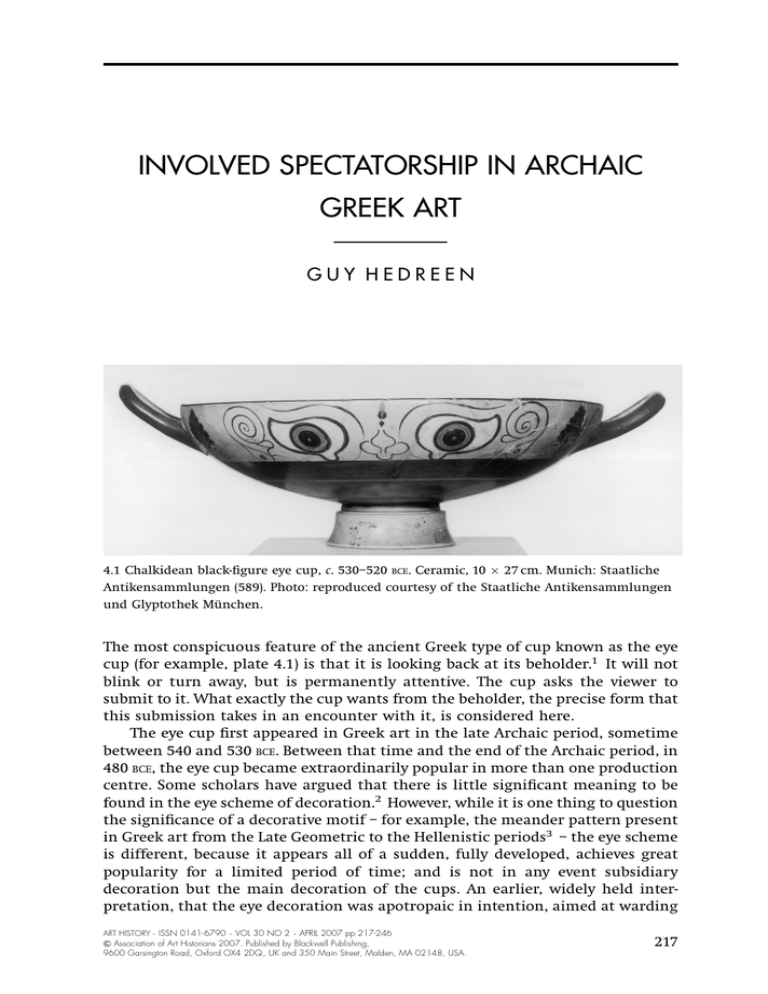

4.1 Chalkidean black-figure eye cup, c. 530–520 BCE. Ceramic, 10 27 cm. Munich: Staatliche

Antikensammlungen (589). Photo: reproduced courtesy of the Staatliche Antikensammlungen

.

und Glyptothek Munchen.

The most conspicuous feature of the ancient Greek type of cup known as the eye

cup (for example, plate 4.1) is that it is looking back at its beholder.1 It will not

blink or turn away, but is permanently attentive. The cup asks the viewer to

submit to it. What exactly the cup wants from the beholder, the precise form that

this submission takes in an encounter with it, is considered here.

The eye cup first appeared in Greek art in the late Archaic period, sometime

between 540 and 530 BCE. Between that time and the end of the Archaic period, in

480 BCE, the eye cup became extraordinarily popular in more than one production

centre. Some scholars have argued that there is little significant meaning to be

found in the eye scheme of decoration.2 However, while it is one thing to question

the significance of a decorative motif – for example, the meander pattern present

in Greek art from the Late Geometric to the Hellenistic periods3 – the eye scheme

is different, because it appears all of a sudden, fully developed, achieves great

popularity for a limited period of time; and is not in any event subsidiary

decoration but the main decoration of the cups. An earlier, widely held interpretation, that the eye decoration was apotropaic in intention, aimed at warding

ART HISTORY . ISSN 0141-6790 . VOL 30 NO 2 . APRIL 2007 pp 217-246

& Association of Art Historians 2007. Published by Blackwell Publishing,

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

217

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

off evil, at least had the merit of assuming that the motif had some specific

function or meaning. The difficulty with the apotropaic interpretation of the

cup’s eyes is that it attempts to account for a sophisticated pictorial conception in

terms of primitive superstitious belief in the absence of any positive evidence

connecting the two phenomena. A related visual motif in Greek art, the gorgoneion

(the frontal face of the legendary gorgon Medusa), is also accorded powerful

apotropaic force, both in ancient mythology and modern scholarship. Yet the

extraordinary popularity of the gorgoneion as a visual motif attests to its ineffectiveness as an apotropaic device in any literal sense, a point that even some

ancient writers recognized. In a recent article in this journal, Rainer Mack

proposed a new interpretation of the gorgoneion that contextualizes it within

ancient artistic practices of visual narration and pictorial convention, rather than

notions of primitive magical belief.4 I take an approach similar to Mack’s in this

study of eye cups. It is important to recognize, as several scholars have demonstrated, that the faces of eye cups, like the face of the gorgoneion, represent the

faces of particular mythological individuals or types of mythical characters (silens

[also known as satyrs], nymphs and perhaps Dionysos the god of wine). The eye cup

and the gorgoneion are characterized by similar manipulations of pictorial

conventions, including eye contact between the represented figure and the viewer

as well as the elimination of pictorial space within the image. The effect of those

manipulations, I argue, is to put the viewer into the position of being an interlocutor – a counterpart within the mythical world – of the gorgon, silen, or

nymph represented on the vase. Explaining precisely how the visual motifs

encourage that response is the principal aim of this essay.

It is also argued that this particular mode of pictorial engagement with a

viewer is not unique to ancient art. Richard Wollheim’s model of a spectator

within a representation, with whom the beholder of the work identifies, helps to

clarify how the interpretation advanced in this paper differs from the interpretation of Norbert Kunisch and others, which holds that the eye cup functioned

as a mask for the user of the vase. I also show that this mode of pictorial

engagement is not limited in ancient art to gorgoneia or eye cups, but also characterizes some representations of silens shown en face, with a frontal face.

Although my arguments are based primarily on the formal analysis of the

pictorial conceptions of eye cups and other works of ancient visual art, they can

be supported by consideration of the formal characteristics of some poetry

performed during symposia, which are the most likely context in which the vases

in question were originally experienced. The poetry employs literary conventions

(first-person narrative forms, the re-performance aloud over generations of

traditional poems in the symposium) that facilitated the temporary adoption of

fictional personae. Both poetry and vase-painting afforded symposiasts the

opportunity, provided them with an incentive, or induced them temporarily to

identify with fictional or mythical figures. Contextualizing eye cups, gorgoneia

and en face silens more broadly, I argue that there are affinities between the kind

of engaged spectatorship informing those works and certain structural features

of early Greek drama as examined by Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche’s description

of the twofold experience of inhabiting a dramatic role or persona, on the one

hand, and being aware of oneself in the role, on the other, is not fundamentally

different from Wollheim’s model of engaging with a spectator in a picture: that

218

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

is, a beholder taking on the point of view of a spectator located conceptually within

the virtual world of a picture yet spatially on the spot where the beholder is located.

Perhaps because of the schematic nature of the decoration of eye cups or the

gorgoneion as a visual motif, many scholars have tended to look to comparative

folklore rather than to the history of art for insights into the significance of those

visual artefacts. Nietzsche’s analysis reminds one that the visual motifs were

circulating at a time when the Greeks were developing particularly sophisticated

forms of mimetic poetry and drama, forms that had special interest in the

experience of both performers and audience. There is no inherent reason why the

pictorial forms of that time may not have been just as sophisticated.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF EYE CUPS

The cup now in Munich (plate 4.1) belongs to the so-called Chalkidean workshop

of Archaic Greek pottery. The decoration of cups from this production centre

always includes a pair of eyes on each exterior side. It usually includes a nose and

4.2a and 4.2b Chalkidean black-figure eye cup, c. 530–520 BCE. Ceramic, 13.7 27.6 cm. New York:

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of F. W. Rhinelander, 1898 (98.8.25). Photos: all rights reserved,

The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

219

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

ears as well. Occasionally, in place of the ears or nose, one encounters silens,

nymphs, vases, flowers, or sphinxes (plate 4.2).5 In Archaic Athenian vasepainting, there is a comparable series of cups bearing a pair of eyes, usually also a

nose, and occasionally ears.6 Possibly the earliest extant Athenian eye cup is the

one signed by the innovative potter Exekias and dated around 535 or 530 BCE (plate

4.3).7 In his study of Chalkidean vases, Andreas Rumpf argued that no extant

Chalkidean eye cup is likely to be earlier than the cup signed by Exekias. But he

pointed out that the eye cup appears with suddenness in Athenian vase-painting,

at a time when it was dominated by other shapes and schemes of decoration of

cups. He suggested that a Chalkidean eye cup earlier than any now known might

have been the source of inspiration for the Athenian series.8 It seems unlikely,

however, that the Athenian eye cup in its entirety derives from Chalkidean

models. The shape of most Athenian eye cups differs from Chalkidean cups in the

4.3 Athenian black-figure type A cup, c. 535–530 BCE, Exekias. Ceramic, 13.6 30.5 cm. Munich:

Antikensammlungen (2044). Photo: courtesy of the Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyp.

tothek Munchen.

bowl and foot; Exekias’s cup, for example, does not have a drum-shaped foot. Hans

Bloesch has demonstrated that the Athenian shape, known as type A, originated

within Athenian pottery workshops.9 The scheme of decoration employed on type

A cups also rarely includes ears, which are common on Chalkidean eye cups. The

two series of eye cups, Chalkidean and Athenian, might derive independently

from the so-called ‘eye bowls’ manufactured in East Greece from the late seventh

to the mid-sixth centuries.10 Alternatively, all three series may be independent

manifestations of a pictorial conception that is the chief subject here.

WHO’S AFRAID OF THE EYES ON A CUP?

The eyes staring out from the cup have often been understood to be apotropaic in

intention, a magical means of warding off ill effects or evil forces.11 The interpretation has been supported with reference to the modern Greek practice of

pinning a small blue glass eye to a person’s clothing – to ward off the ‘evil eye’, as

it is called – though evidence of continuity between the modern practice and

Archaic Greek culture is hard to come by. There are, however, numerous difficulties with any simple apotropaic interpretation of eye cups, as Didier Martens,

among others, has shown.12 Adherents of this theory cannot agree on what is

220

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

being protected by the pair of eyes: do they protect the wine contained in the cups

from impurity, or the cups themselves from breakage during shipping? If the eyes

protect the users of the cups from harm, what kind of harm was envisioned? As

Norbert Kunisch put it, why should a drinker, in the midst of his companions, in

the relative safety and comfort of the symposium, feel a need for such protection?13 Is it conceivable that the function of such a sophisticated and popular

ceramic invention is nothing more than a desire to ward off the jealousy of

servants, as W. Hildburgh suggested?14 If the function of the eyes is essentially a

primitive one, why does the popularity of the motif occur only relatively late in

the history of Greek ceramics? And if the decorative scheme were magically

effective, then why did the fashion die out so quickly and completely around the

end of the Archaic period?15 Can a traditional magical practice lose its perceived

effectiveness overnight? If the intention of the decoration were magical, would

not one eye suffice? After all, the modern custom is to wear a single eye, not a

pair.16 Most significantly, the apotropaic interpretation does not explain the

decoration of the eye cup in its entirety. The earliest eye cups – East Greek,

Chalkidean and Athenian – almost invariably include a nose in addition to the

eyes; and the Chalkidean cups very often include ears as well. Eyes, ears and nose

together, arranged symmetrically on the exterior of the cup, make up a frontal

face. From time to time, the nose or ears were replaced by other motifs, but the

original conception of the eye cup in all three fabrics is that of a face, not just a

pair of eyes.17

THE GORGONEION

The strongest argument in favour of an apotropaic interpretation of the eye cup

has always been the argument that connects the face with the gorgoneion, the

disembodied frontal face of the

gorgon Medusa (for example, Munich

N. I. 8760, plate 4.4). The gorgoneion is

among the earliest known monsters

in Greek art. Over the course of

centuries, the image occurs, it seems,

in every context in which a circular

pictorial motif might be called for.18

In suggesting that the eyes of the eye

cup were apotropaic in origin, J.D.

Beazley argued that they were sometimes thought of as gorgon’s eyes.19

On several eye cups (as, for example,

that in plate 4.3) there are one or

more dots above the eyes, on the

forehead of the face, so to speak.

Beazley suggested that the dots

represent a kind of artificial beauty 4.4 Athenian black-figure plate, c. 560 BCE, Lydos.

mark or mole that mothers occasion- Ceramic, diameter 24 cm. Munich: Staatliche

ally depicted on the foreheads of their Antikensammlungen (N. I. 8760). Photo: courtesy

babies, in order to diminish the of the Staatliche Antikensammlungen und

.

beauty of the child and, in that way, Glyptothek Munchen.

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

221

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

4.5a and 4.5b Athenian red-figure pelike, c. 470–450 BCE, Hermonax. Ceramic, height approx.

20 cm. Rome: Villa Giulia. Photos: courtesy of the Soprintendenza per i beni archeologici

dell’Etruria meridionale.

ward off envy, one root of the evil eye.20 Whether or not Beazley’s interpretation

of the dots is correct, the fact remains that they are very common in representations of the gorgoneion (as in plate 4.4). When the dots occur as part of the

imagery of eye cups, the decoration as a whole, including the round shape of the

bowl, resembles the gorgoneion.21 It is true that the dots are not restricted to

representations of the gorgoneion, occurring on occasion in vase-paintings of

silens or masks of Dionysos, but it is nevertheless hard to deny that the eye cup

and the gorgoneion share the qualities of disembodiedness and stark frontality, as

well as the occasional beauty mark.22 Most Athenian eye cups contain a representation of the gorgoneion in the centre of the bowl, which would have facilitated

the comparison of the eye scheme and the gorgoneion by the maker and user of the

cup. On a few eye cups, the gorgoneion is brought directly into close, formal

relation to the eyes on the exterior surfaces. On the outside of an eye cup in

Madrid, the gorgon herself occupies the space between the eyes.23 On an eye cup

in Cambridge the pupils of the eyes on the exterior are filled by gorgoneia.24 It

appears that the two visual motifs or decorative schemes, eye cup and gorgoneion,

were understood to be intrinsically related in some important way.

For the apotropaic interpretation of the eye cup, what has always been

important about the gorgoneion is its association with the myth of Medusa,

because the myth explicitly connects her gaze with a dangerous magic. The word

gorgoneion derives from the name ‘Gorgo’, a synonym for Medusa. She was the

222

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

mortal member of a trio of gorgon sisters, grandchildren of the dark and

mysterious depths of the primeval sea Pontos. In the myth Perseus cut off and

carried away Medusa’s head; he gave the head to Athena, who affixed it to her

special defensive armour, the aegis, as a repellent device, for the head of Gorgo,

even after its separation from its body, had the very special effect of turning to

stone whosoever looked it in the eye.25 It is certain that the monster’s head

possessed this power, because Perseus used it to transform the Titan Atlas into a

mountain of stone in North Africa (Ovid, Met. 4.631–62);26 to turn to stone those

who interfered in his plan to marry Andromeda (Ovid, Met. 5.177–235); and to

petrify Polydektes for harassing his mother Danai. The use of the head to turn

Polydektes to stone is attested as early as Pindar (Pyth. 10.46–48, first half of the

fifth century BCE), who specifies that the power of the gorgon’s look was enough to

petrify the entire population of the island of Seriphos. The use of the head against

Polydektes is also attested in fifth-century vase-painting, as on an Early Classical

pelike by Hermonax (plate 4.5).27 But the power of the gorgon is already given

visible form in the earliest surviving representation of the beheading of Medusa

by Perseus. On a Cycladic relief pithos of around 670 BCE (plate 4.6) the danger

contained in the gorgon’s eyes is attested by the precaution taken by Perseus, who

averts his gaze and uses his sense of touch to guide his sword to her neck.28 The

averting of the gaze, which becomes a traditional feature of the iconography of

Perseus, indicates that Medusa already

possessed the power to kill with her

eyes when she became a subject of

narrative art.29

The relief pithos and other early

representations of the story of Perseus

and Medusa also show that the principal traits of the face of Medusa in art

are those of the disembodied gorgoneion.30 The round frontal face in art

that is the closest parallel for the eye

cup is inextricably bound up with a

traditional mythical narrative. Typical

features of gorgoneia – the big, toothy, 4.6 Cycladic relief pithos, c. 670 BCE. Ceramic,

fanged grin, the lolling tongue, squa- height 130 cm. Paris: Musée du Louvre (CA 795).

shed nose, spit-curled hair, central Photo: courtesy of the Réunion des musées

parting, and, above all, stark frontality nationaux/Art Resource, NY.

– characterize the face of the living,

breathing Medusa on the Corfu pediment of 590 BCE (plate 4.7), the gorgon at the

moment of her death on a mid-sixth-century vase by the Amasis Painter, and

many other representations of Medusa in Archaic narrative art.31 Even the relatively less monstrous conception of Medusa on the Early Classical hydria by the

Nausikaa Painter (plate 4.8) – sleeping imperturbably as Perseus creeps towards

her with his knife ready (he can look directly at her because her eyes are closed) –

retains the wide-open mouth, central parting, and frontality of the traditional

gorgoneion.32 The early monumental pedimental sculpture of the gorgon from the

temple of Artemis at Corfu (plate 4.7) suggests that the defeat of Medusa by

Perseus is part of the very conception of the monster, even when she is depicted

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

223

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

4.7 Pedimental sculpture,

temple of Artemis, Corfu,

c. 590 BCE. Marble, height

279 cm. Corfu: Archaeological

museum. Photo: Hermann

Wagner, Deutsches arch.aologisches Instituts Athen,

neg. no. D-DAI-ATH-1975/885.

All rights reserved.

4.8 Athenian red-figure hydria,

c. 460–450 BCE, Nausikaa

Painter. Ceramic,

44.5 33 cm. Richmond:

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

(62.1.1), Arthur and Margaret

Glasgow Fund. Photo:

rVirginia Museum of

Fine Arts.

224

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

alone: in the pedimental sculpture, the

gorgon is identified as Medusa (rather

than one of her immortal sisters)

through the inclusion in the composition of Pegasos and Chrysaor, and

they call attention to the beheading of

Medusa by Perseus, because they

emerged from the creature’s neck only

when her head was removed.33 The

identity of the head of the mythological figure Medusa and the isolated

gorgoneion is eloquently established on

a pelike by the Pan Painter (plate 4.9):

it shows Perseus holdingthe head of

Medusa, which he has just removed

from its body and which takes the

form, visually, of the gorgoneion. The

vase-painting leaves no room for doubt

that the ubiquitous artistic motif

known as the gorgoneion was created in

the course of a traditional heroic deed;

intrinsic to the visual motif is a

narrative significance.34

The vase-painting by the Pan

Painter also neatly illustrates the

problem with any simple apotropaic

interpretation of the gorgoneion.

Perseus turns his own head away from

the image, because to look directly at 4.9 Athenian red-figure pelike, c. 470–460 BCE,

the face would, he knows, turn him to Pan Painter. Ceramic, height approx. 20 cm.

stone, but he directs the face of Munich: Staatliche Antikensammlungen

Medusa directly at the viewer, so that (8725). Photo: courtesy of the Staatliche

it is impossible to consider the vase- Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek Munchen.

.

painting at all without doing the one

thing that the myth guarantees we

cannot do: look the gorgoneion directly in the eye. Françoise Frontisi-Ducroux has

argued that the visual artists regularly employed a special formal strategy, a

double apostrophe, in depicting the death of Medusa: Perseus averts his gaze from

the paralysing effect of the gorgon’s look, and the gaze of the gorgon is also

averted from anyone within the narrative plane of the image. The vital necessity

of avoiding the gaze of the gorgon is expressed in the visual representations not

only by Perseus’s action but also by making it impossible for any of the figures

within the visual narrative to catch the eye of the gorgon; they cannot look her in

the eye, because she is looking at us.35 The formal visual means of conveying the

impossibility of enduring eye contact with Medusa, however, undercuts the efficacy of the image, because the Medusa’s gaze is invariably endured by anyone who

encounters the work of art from outside the virtual world of the visual narrative.

As Mack nicely put it, the question is ‘why it made sense to articulate a monstrous

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

225

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

power only in order to ‘‘defeat’’ it’.36 The artists could have turned the regard of

the gorgon so that the gorgon would avoid the gaze of both the protagonist in the

story and the beholder of the visual narrative. There would be no risk in viewing

an image of the gorgon, and no art-historical problem to solve.37

In attempting to explain the ineffectiveness of visual representations of the

gorgon’s frontal regard, some scholars have argued that the story itself, the

testimony to the potency of the image, is a secondary development. In Thalia

Howe’s account of the development of the imagery, the gorgoneion is, in origin, a

primitive mask – that accounts for its frontality – and it existed before any myth

about a dangerous gorgon.38 The notion that the mask of the gorgon preceded

the development of a mythology about the creature is a good example of the early

twentieth-century scholarly tendency to privilege ritual and discount the

importance of mythology as ‘ritual practice misunderstood’, as Jane Harrison

famously put it.39 It necessitates an account of the creation of the story in which

a misunderstanding on the part of the storytellers is central. For example, Howe

argued that ‘[a]lthough the gorgoneion, rather than the Gorgon, was the original

element in the myth, the Greeks, not realising that fact, soon after its appearance

reasoned that it must have belonged to a figure which had been decapitated.’40 As

noted earlier, however, art-historical research has revealed that the narrative is as

early as the disembodied image of the monster’s head. The belief that the

disembodied head of Medusa had a prior existence independent of any narrative

entanglement rests entirely on theoretical speculation about the nature of the

relationship between ritual and myth.

A more productive explanation of the failure of the gorgoneion to petrify the

beholder takes its point of departure from a type of vase-painting that first

appears in the fourth century BCE. Those vase-paintings depict Perseus and Athena

contemplating the reflection of the gorgon’s face in a pool of water or polished

shield in a quiet moment after the hero has accomplished the decapitation (for

example, plate 4.10).41 The vase-paintings advance a nuanced understanding

about the regard of the gorgon: it paralyses only those who look at it in a direct

and unmediated fashion. A similar conception informs Ovid’s account of the

beheading of Medusa (Met. 4.782–786), in which Perseus positions a polished

shield in such a way that he is able to guide his sword visually to its target and

accomplish a clean, effective beheading without looking directly at his prey. The

visual representations of Medusa and gorgoneia are similar to the reflections of

the gorgoneion in a pool or polished shield in so far as they are images of the

monstrous head, not the head itself.42

It is very likely, however, that the specular motif originated at the end of the

fifth century BCE, when it first appears in art, and not earlier. Jean-Pierre Vernant

argued that the use of reflection is a narrative development related to other

intellectual trends of the late fifth century, including the rise of perspectival

illusion in painting, theories of mimesis in philosophy, and developments in

optical science.43 Moreover, the widespread image in earlier Greek art of Perseus

looking away from Medusa as he kills her shows that Archaic artists had developed a means of conveying the story without resorting to the use of reflective

devices.44 It seems fair to assume that early Greek artists and viewers recognized

that they survived direct visual encounters with the frontal gorgoneion because

they were looking at representations of it, rather than at the actual head of the

226

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

4.10 Apulian red-figure bell krater, c. 400–380 BCE, Tarporley Painter.

Ceramic, height 30.5 cm. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts (1970.237), gift of

Robert E. Hecht, Jr. Photo: rMuseum of Fine Arts, Boston.

monster. But one may doubt that they conceptualized the reason for their

survival in the analytical or formal manner in which, say, Aristotle attributes the

pleasure people take in contemplating accurate representations of things that are

painful to look at in themselves (for example, ugly animals, corpses) to universal

human impulses to make representations, enjoy them, and learn from them.45

How the frontal image of the gorgon’s fatal gaze was experienced before the

late fifth century has only been adequately accounted for by Rainer Mack. Mack

emphasizes that the fiction of the gorgon’s deadly visual power is embedded in an

overarching story in which the danger of the gorgon’s look is overcome by

Perseus. As vase-painters or pottery users took up the image of the gorgoneion, they

pierced the fiction of the unsustainability of its gaze, and in doing so, they

replicated the legendary victory of Perseus over the monster.46 Mack suggests that

the image of Medusa, even the gorgoneion, depicts not merely the petrifying power

of the monster’s gaze, but more specifically a power that was overcome by

Perseus. ‘The viewer, by this account, played the role of Perseus, and in the simple

act of viewing the image . . . re-enacted his heroic triumph over the monster . . .

The image is not illustrating an object in the legend (the severed head) but staging

an episode from the legend.’47 Mack’s thesis locates the effectiveness of the

frontal gorgoneion not in primitive magical belief but in the practice of visual

narration and the structure of the motif’s pictorial conception.

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

227

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

W H O S E F A C E D E C O R AT E S T H E E Y E C U P ?

The eye cup has important affinities with the gorgoneion beyond the formal

characteristics already enumerated. Like the gorgoneion, which is the face of a

particular notorious individual, the face on many, if not all, eye cups is not

generic. And like the gorgoneion, the eye cup also invites the viewer to insert himor herself into a specific mythological context. Gloria Ferrari has emphasized that

there are at least two specific types of figures represented on Chalkidean eye cups.

On many cups (for example, the so-called Phineus cup, obverse, plate 4.11a) horse

ears indicate that the face is that of a silen. In other instances (Phineus cup,

reverse, plate 4.11b) human ears with earrings, often combined with a form of eye

lacking a pronounced tear duct, suggest a female face.48 The female faces are

usually identified as the faces of nymphs, companions of silens.49 Matthias

Steinhart demonstrated why the decorative programme of the Phineus cup in

particular suggests that the female counterpart to the frontal silen face on

Chalkidean eye cups is a nymph. One side of the exterior is decorated with two

eyes, a nose and a pair of silen ears, the other with a pair of eyes lacking

pronounced tear ducts, a nose and two human ears with earrings. Between each

handle and ear there is a pair of figures – one silen and one female figure in each

vignette – echoing the juxtaposition of the two different frontal faces on the cup.

That the female companions of the silens in the four vignettes are nymphs is

suggested by their intimacy with the silens – they are even engaged in sexual

intercourse on one side of the cup. In the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite (262–63), as

well as numerous later sources, the mythical sexual companions of silens are

always nymphs.50

4.11a and 4.11b Chalkidean black-figure eye cup, c. 525 BCE, the so-called Phineus cup. Ceramic,

.

12 39 cm. Wurzburg:

Martin-von-Wagner Museum der Universit.at (L 164). Photos: Courtesy of

the museum/K. Oehrlein.

228

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

4.12 Athenian black-figure Chalkidizing eye cup, c. 520 BCE, signed by the potter Nikosthenes.

Ceramic, 9.5 35.9 cm. Houston: De Ménil Collection (70–50-DJ). Photo: courtesy The Menil

Collection, Houston.

Silen ears also occur on Athenian eye cups that imitate Chalkidean models in

shape and decoration, the so-called ‘Chalkidizing’ cups. The most important

example is a cup in Houston signed by the prolific Athenian potter Nikosthenes

(plate 4.12). In shape, the cup appears to have been modelled directly on an early

form of the Chalkidean cup with broad bowl and drum-shaped foot; its decoration, especially the line connecting the nose to the silen ears, is also very close to

the Chalkidean scheme of eye-cup decoration.51 There are also a few Athenian eye

cups with ears that are not Chalkidizing in shape.52 Other characteristics of

Athenian eye cups have been taken to indicate that the frontal face is that of a

silen, or that more than one type of figure is represented by the faces. FrontisiDucroux suggested that the snub nose represented on many Attic eye cups

resembles the characteristic squashed nose of a silen.53 For Jette Keck, in Athenian workshops, unlike Chalkidean ateliers, the handles of the eye cup may have

been envisioned as the ears of the painted face.54 The pointed profile of the

upturned handles of the cup might specifically suggest the pointy ears of the

silen. Kunisch has emphasized that, on Athenian eye cups, there is more than one

type of eye, the masculine as well as feminine eye, which suggests that the faces of

Athenian eye cups represent several specific types of faces, most notably silens

and nymphs, and not merely the human face in the abstract.55 A few Athenian

eye cups, such as the so-called Bomford cup (plate 4.13), bring the face of the eye

cup into close proximity to the frontal face of the silen.56

Two other figures have also been identified in the faces on eye cups. The most

plausible identification is that of Dionysos. Evelyn Bell and Gloria Ferrari

suggested that the eye cup may derive from, or occasionally represent, the frontal

face or mask of Dionysos.57 Ferrari suggested that the earrings adorning the ears

on some Chalkidean eye cups need not rule out the possibility that the human

ears were those of a male figure, such as Dionysos. And she noted that, on a

number of Attic eye cups, a frontal mask of Dionysos is depicted between the eyes,

sometimes with the mask of a silen on the reverse of the cup. Matthias Steinhart

has argued that the Athenian eye cup represents the face of a particular Diony& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

229

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

sian animal, the panther, which is always depicted in Greek art in frontal

aspect.58 In sum, the faces on most eye cups, Chalkidean or Athenian, appear not

to be generic but to represent the faces of specific types of creatures: many

Chalkidean, and some Athenian, eye cups represent the faces of silens; some

others most probably depict the faces of nymphs; and some possibly convey the

face of Dionysos or a panther. In general, the creatures all seem to belong to the

mythical circle of Dionysos.

The recognition that eye cups represent certain types of characters was an

important step because it encouraged the consideration of the cups in connection

with the practice of masking, rather than apotropaic magic. John Boardman

noted that the face of the eye cup acquires a general mask-like character specifically when the cup is used for drinking: ‘consider one raised to the lips of a

4.13 Athenian black-figure eye cup, c. 530–520 BCE, manner of the Lysippides Painter, the so-called

Bomford cup. Ceramic, 13.8 34 cm. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum (1974.344). Photo: courtesy of

the Ashmolean Museum.

drinker: the eyes cover his eyes, the handles his ears, the gaping underfoot his

mouth.’59 Kunisch developed this idea further. The face was not just a symbol of a

mask, it became a veritable mask when the cup was used for drinking: the eye cup

transformed the symposiast, for his fellow symposiasts watching him lift the bowl

to his face, into a silen, nymph, or some other Dionysiac figure.60

The interpretation of the eye cup as a mask that covers the face is attractive,

but it is not without difficulties. Frontisi-Ducroux objected to the idea that the

drinker offered a false face to his fellow drinkers.61 The conception of a mask as

something that conceals the identity of the figure wearing it is, she argues, a

modern idea. Judging from Ancient Greek literature, the mask was employed to

effect an identification of the wearer with some other figure, not to conceal the

wearer’s own identity.62 Kunisch believed that the drinker could never don the

mask of the god Dionysos, and thus discounted the possibility that any of the

faces on eye cups represented the face of the god.63 For Martens the interpretation of the eye cup as a mask cannot account for the meaning of the many eye

schemes that decorate other pottery shapes, such as neck amphoras or kraters.

Those shapes do not regularly cover the faces of drinkers, and yet they are

230

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

frequently decorated with the same kind of decoration as eye cups. To treat the

eye scheme of decoration on amphoras and kraters as dependent for its inspiration on the eye cup merely begs the question of how it might have been understood on those vessels which cannot be used as masks.64 Those objections rightly

call into question an interpretation of the eye cup that limits its effect to only

those moments when the cup passes in front of the face of the drinker and

provides him visually with a new facial identity.

In the debate about the status of the eye cup as a mask, the full significance of

the frontality of the image – of the eye contact that the represented figure makes

with us – has been lost sight of. The gaze of the frontal face is so unremitting as to

endow the figure with a high degree of attentiveness. The unflinching gaze gives

the impression that the figure is actively looking for something or someone. The

possibility of identifying the faces on eye cups as specific types of figures

contributes significantly to determining what specifically the figures may be

hoping or expecting to see. For example, recognizing that the gorgoneion was

created by Perseus in an heroic confrontation with the monster Medusa suggests

that the gaze of the gorgoneion is directed at her destroyer. Medusa hoped to stop

him in his tracks with her petrifying gaze, but the round shape of the motif

implies that he has already succeeded in beheading her. Perseus caused her gaze

to be fixed forever, through rigor mortis, as it was the moment when she

encountered him. In other words, familiarity with the narrative context in which

the gorgoneion belongs helps the viewer to determine who the gorgoneion is looking

at. In the case of eye cups, silens, nymphs and Dionysos also derive from narrative

mythology.65 Silens and nymphs are the most frequent companions of the god

Dionysos, and they are collective identities – they are always open to broader

membership. On the François vase (Florence: Museo Archeologico Etrusco) of

around 570 BCE, the most informative extant painted vase on matters of

mythology, containing ten different visual narratives and over one hundred

personal names identifying the figures, the silens and nymphs are unusual in

having collective, not individual, labels.66 In Archaic Greek vase-painting, silens,

nymphs and Dionysos are most often seen in the company of each other, often in

the company of as many silens and nymphs as could be fitted into the available

space.67 A silen, nymph, or Dionysos, looking attentively at something, is most

likely gazing at another silen or nymph, or perhaps at the god.

The viewer is drawn into the scene by the direction in which the silen, nymph,

or god is looking. He or she, looking for a companion silen or nymph, makes eye

contact with us, the viewers of the vase. Consider again the case of the gorgoneion:

Medusa has just encountered her destroyer, because the myth assures us that the

head belonged to a body, and the round, disembodied form of the image implies

that it has been successfully removed. The hero is obviously not present within

the narrative plane of the image, where protagonists are almost invariably to be

found in Greek narrative art – there is no room for him there. The direction of the

monster’s attention suggests that Perseus is to be found where the viewers of the

image are located. Like the gorgoneion, the eye cup does not provide a pictorial

space within which the vigilant frontal face can find what it is looking for. The

space in which the face must look is the space of the viewer of the cup. This

pictorial structure implicitly encourages the viewers of the vase, I believe, to

adapt their response to the frontal face as if they were the persons or type of

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

231

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

figure that a silen, nymph, Dionysos, or Medusa would expect to see in the space

before them.

T H E S P E C TAT O R I N T H E P I C T U R E

To understand how Archaic Greek vase-paintings specifically elicit such a

subjective experience cross-cultural and trans-historical comparisons may be

helpful. In his study of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century group portraiture

of Holland, Alois Riegl observed that Dutch artists developed a means of engaging

a viewer’s imagination, not merely his or her powers of observation.68 They

directed the attention of some (or all) of the figures within a painting towards a

person (or persons) not depicted in the image but necessarily – due to the

directions of the figure’s (or figures’) gaze(s) – occupying the place taken by a

viewer of the painting. Riegl noted that a figure within such a painting usually

responds to the undepicted figure(s) in such a way that their character or the

nature of the encounter is discernible. Of Rembrandt’s Syndics: The Sampling Officials of the Amsterdam Drapers’ Guild of 1662 (plate 4.14) he wrote,

.

Burger-Thoré

was the first to describe the dramatic content. Above all, he correctly presumed

the presence of an unseen party in the space of the viewer, with whom the syndics are negotiating. The presiding officer is presenting the guild’s position – with which the party in

question presumably disagrees – in such a superior and cogent way that his colleagues, the

moment they hear his convincing argument, gaze triumphantly at their humbled opponent.

This interpretation is no doubt broadly correct, though Thoré, as a Frenchman, overly

dramatised the situation and invented an all too sharply polemical contrast between the

regents and the presumed party. To a dispassionate observer, the expressions of the figures and

the general mood of didactic attentiveness probably convey more a feeling of contentment and

assent than malicious satisfaction and schadenfreude.69

The figures in the painting respond to one or more persons occupying the

viewer’s position, not as if those persons were visitors to an art museum but as if

they had an interest in cloth or some other business with the guild.70

Riegl seemed to think that the location of the unseen protagonist(s) of that

sort of picture was more than an accident or coincidence, but he was not very

precise about its significance. He frequently spoke of the viewer of the painting

and the unseen protagonists as if they were interchangeable. Of Hals’s Banquet of

the Officers and Junior Officers of the Civic Guard of Saint George (1616, Haarlem: Franz

Hals Museum) Riegl contended: ‘[the] banqueting guardsmen . . . have a variety of

active and passive relationships with the viewer: that is to say, with the arriving

guests whom some of them have just spotted, but who are invisible to the

viewer.’71 The appearance of this kind of pictorial conception in the history of art

represented for Riegl an important step towards an art directed to the subjective

involvement of the spectator: ‘[t]he artists of Holland were the first to realize that

the viewing subject can take mental control over all the objects in a painting by

making them part of the viewing subject’s own consciousness.’72

Richard Wollheim refined the understanding of this sort of representation in

two important ways. First, paintings of any date, in principle, can ‘have a representational content in excess of what they represent. There is something which

232

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

4.14 Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, Syndics: The Sampling Officials of the Amsterdam Drapers’

Guild, 1662. Oil on canvas, 191 279 cm. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum (inv. no. SK-C-6).

Photo: r Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

cannot be seen in the painting: so the painting doesn’t represent that thing. But

the thing is given to us along with what the painting represents: so it is part of

the painting’s representational content.’73 Paintings that contain an unrepresented protagonist are not necessarily limited to seventeenth-century Europe.

Second, the implied location of the unseen protagonist(s), not merely in front of

the picture plane but more or less exactly where the spectator of the picture takes

up his or her position, is of particular significance. The purpose of incorporating

an unseen, internal spectator into the representational content of the painting is

to provide us, the external spectators, with a special means of perceiving the

content of the work of art. ‘[A]dopting the internal spectator as his protagonist,

[the external spectator] starts to imagine in that person’s perspective the person

or event that the painting represents . . . [he] identifies with the internal spectator,

and it is through this identification that he gains fresh access to the picture’s

content.’74 Paintings that successfully incorporate an internal spectator provide

enough information about the identity or personality of that figure that the

viewer or external spectator can adopt that character as a point of view.

Wollheim envisioned one objection to the concept of a spectator in the

picture that is especially relevant here: that the spectator in the picture is not

distinct from the spectator of the picture.75 In that regard, Wollheim clarified a

distinction between two types of pictures: those, on the one hand, that invite the

spectator to identify with a figure within the represented space; and paintings, on

the other, in which ‘we are expected to believe on the basis of what we see that a

represented figure enters our space’.76 The differentiation is especially important

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

233

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

in the case of eye cups. When an eye cup was lifted to the face of the drinker, and

its painted face covered his actual face, one might plausibly say that the painted

figure on the cup entered the space of the drinker’s companions, and that it was

part of the intention of the potter and/or vase-painter that the cup create such an

impression when used for drinking.77 Equally, as I suggest here, when the eye cup

is not held up to the face of drinker, its painted face invites a different kind of

response, one that accords with Wollheim’s notion of a spectator in the picture.

When the cup is not being used as a mask, the painted frontally facing mythological figure does not enter the space of viewer; rather, the beholder is invited to

identify imaginatively with a figure within the mythical space of Dionysos and his

followers. As Wollheim emphasized, ‘[t]he impossible thing is for the spectator to

enter the represented space, given, that is, that he doesn’t belong there, or hasn’t

been put there by the artist.’78

In short, the pictorial conception described by Riegl and Wollheim is similar, I

believe, to the conception of the Archaic Greek visual image of the gorgoneion and

the eye cup. In those works of art, the figures within the painted decoration make

eye contact with a figure of a particular sort in front of them. The localization of

the unrepresented figure in the position that we occupy as spectators encourages

us to adopt the figure’s story or role as a point of view.79 This not only accounts

for the fact that the faces on many cups are those of specific figures, such as silens

or nymphs, but also suggests that the eye cup was designed to facilitate imaginative engagement whether or not it was lifted to the face of a drinker. The

traditional apotropaic interpretations of the eye cup and the gorgoneion are not

completely off the mark in seeing the images as particularly powerful. The source

of that power, however, is the insistent claim made on the viewer by the attentiveness of the figures. It relies on formal artistic choices rather than magic.80

T H E E N FA C E S I L E N

The hypothesis that the decoration of the eye cup often serves as an invitation to

adopt the persona of a silen is supported by the pictorial conception underlying

some vase-paintings of silens shown en face or with a frontal face, who make eye

contact with the viewer (for example, plate 4.15). The narrative significance of

the isolated gorgoneion is clarified in part by the many representations of the story

of Perseus and Medusa in which the face of the living monster is that of the

gorgoneion. Similarly, the invitation imaginatively to join the ranks of silens implicit in many eye cups is explicit in some vase-paintings of frontally faced silens.

Scholars have occasionally argued that the frontal face of the silen, like that

of the gorgon, was apotropaic in function. It will suffice to consider the most

explicit ancient literary assertion that the face of the silen had an apotropaic

effect, because the context of the statement playfully undercuts its very claim. In

the fifth-century BCE satyr play by Aischylos entitled Isthmiastai, the chorus of

silens abandons its allegiance to Dionysos and takes up athletics. In one fragment

of the play, the silens marvel at images of themselves, which they are probably

holding in their hands:

look and see whether this image could [possibly] be more [like] me, this likeness by the Skillful

One; it can do everything but talk! . . . I bring this offering to the god to ornament his house, my

234

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

lovely votive picture. It would give my mother a bad time! If she could see it, she’d certainly run

shrieking off, thinking it was the son she brought up: so like me is this fellow.. . . [L]et each

fasten up the likeness of his handsome face, a truthful messenger, a voiceless herald to keep off

travellers; he’ll halt strangers on their way by his terrifying look.81

It is uncertain precisely what kind of images the silens are holding, but Ferrari

and other scholars have argued that the silens are most likely holding theatrical

satyr masks, which they intend to dedicate in the temple of Poseidon, in imitation

of the practice of dedicating dramatic masks in the Athenian temple of Dionysos

Eleuthereus.82 That practice is known from visual sources, Lysias (21.4), and a

fragment of Aristophanes: ‘ ‘‘can you tell me where the Dionysion is located?’’ ‘‘It is

there where the mormoluke^ia are suspended.’’ ’ The fragment of Aristophanes is

noteworthy because his choice of terminology for the masks, mormolukeia (bogeys,

hobgoblins), conveys the idea that the masks could inspire fear, but nothing in

the fragment suggests that they have such an effect in this context.83 Christopher

Faraone argued that one statement in particular of the silen-chorus in the Isthmiastai suggests that the masks they hold are meant to be understood as terror

masks: each one ‘will halt strangers on their way by his terrifying look

(j

o½bon blepon).’84 The passage as a whole, however, is not unambiguous about

the source of the terror that the images might inspire, for the silens have just said

that the images will frighten their own mother because, it seems, of the high

degree of likeness or verisimilitude: ‘if she could see it, she’d certainly run

4.15 Athenian bilingual amphora, c. 520 BCE, Psiax. Ceramic, approx. 70 38 cm. Madrid: Museo

arqueológico nacional (11008). Photo: courtesy of the Photo Archive, National Archaeology

Museum, Madrid.

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

235

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

shrieking off, thinking it was the son she brought up: so like me is this fellow

˛

˛

; ;

on e’xeyrecen outoB

e’mjerŹB od’

e’stin).’85 Hugh Lloyd-Jones

(doko^

uB em e’I nai t

perceptively noted that the fear that the images might inspire in the satyrs’

mother or in passers-by could also be understandable if the art of portraiture

was thought of as unusual or new at the moment represented in the play.86 Given

the high frequency with which inventions or the foundation of institutions are

treated in satyr play, it seems possible that the silens are to be envisioned as

making the first-ever dedication of masks in a temple, or contemplating the firstever theatrical masks of silens.87 The playful emphasis on the verisimilitude of

the masks would have been greatly enhanced in the actual performance of the

play if the chorus members had been wearing masks identical to the ones that

they were holding. Finally, the tone of the passage – the self-consciousness of the

silens, as they look at the images of themselves and calmly and analytically

describe how frightening they will be to their mother or to strangers – undercuts

the idea that the images were really effective in that way.

The en face silen is often alternatively – and, it seems to me, more correctly –

understood as a means of conveying to the viewer the heightened emotional state

of the silens.88 Frontisi-Ducroux has eloquently explained how the visual motif

gets that idea across formally: the en face figure disengages from visual interaction

with the other figures in the image, and in that way suggests that his or her

attention is elsewhere.89 There are numerous early vase-paintings of silens and

Dionysos together in which one of the silens turns his face away from the god and

towards the viewer, as if to escape from subordination to the deity.90 On an

amphora in Madrid by Psiax (plate 4.15), Dionysos turns around to look at the

silen behind him, because the silen is no longer attending to the god, having

turned his attention towards the spectator.91 The lovely symmetry of the

composition, rooted in the central, transcendent figure of the god Dionysos, is

spoiled by the independent-minded silen, who disregards his master’s claim to his

attention, and perhaps invites some undepicted figure into an otherwise perfectly

balanced, closed composition.

Although it appears in many cases that the en face figure is disengaged from

the other figures within the representation, Frontisi-Ducroux acknowledged that

every frontal face also potentially contains an address to the viewer.92 She argued

that it seems very probable that the original viewers of the vase-paintings would,

in some cases, have seen someone very like themselves reflected in the en face

figure. The likelihood is greatest, she argued, in depictions of such en face figures

as warriors or symposiasts, in which the painted figure’s vocation or identity was

most similar to that of the original viewer, the symposiast examining the vase he

is using. A symposiast named Thoudemos is portrayed on a fragmentary krater by

Euphronios (plate 4.16), staring out over the top of his cup at a viewer who, the

vase-painter could safely have presumed, was also a symposiast similarly holding

a cup.93 Here the en face figure becomes a kind of mirror in which the spectator

sees a reflection of himself. Vase-paintings of the gorgon, eye cups, as well as some

later paintings in the Western tradition, suggest that some en face figures can

alternatively be understood to elicit an otherwise uncharacteristic role from the

spectator. Frontal figures of that sort do not reflect back to the viewer an identity

that he or she already possesses, but invite the viewer to identify temporarily with

characters who may be quite different in lifestyle or values.

˘

˛

236

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

4.16 Fragmentary Athenian red-figure calyx krater, c. 515–510 BCE, Euphronios. Ceramic,

38.3 53 cm. Munich: Staatliche Antikensammlungen (inv. 8935). Photo courtesy of the

.

Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek Munchen.

Some vase-paintings of silens possess a marked visual address to an undepicted silen whose position, as indicated by the depicted figures, is essentially

that of the viewer. One way to understand the address is as a means of putting

the user of the vase into the unseen silen’s shoes, so to speak, despite the

differences in ontological status and way of life. The depiction of three masturbating silens on the aryballos by Nearchos (plate 4.17), one of the very early

representations of a frontally faced silen, provides a good example. The image

is dominated by a silen who looks directly at the spectator.94 One amusing

possibility is that the en face silen has seen someone in the space occupied by the

viewer who has aroused him to his current state of excitement. In Aristophanes’s

Frogs (542–6) Dionysos envisions himself, in an inversion of expected roles,

watching his servant Xanthios embracing a slave girl, and imagines himself

roused to the point of auto-eroticism by the sight. The structure of Nearchos’s

vase-painting, however, encourages a different interpretation. To either side, a

silen identical to the en face silen is depicted in profile. The silens to right and

left face each other and are, in a sense, mirror images. The symmetry between

those two figures encourages the viewer to envision an identical unseen silen

facing the en face silen. The coincidence between the position of the unseen silen

conjured by the pictorial composition, on the one hand, and the position of the

viewer, on the other, encourages the viewer to imagine himself in the role of a

solipsistic silen.

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

237

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

4.17 Athenian black-figure aryballos, c. 560 BCE, Nearchos. Ceramic, height

7.8 cm. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, The Cesnola

Collection, by exchange, 1926 (26.49). Photo: all rights reserved, The

Metropolitan Museum of Art.

S Y M P O T I C P O E T R Y A N D R O L E – P L AY I N G

The interpretation of eye cups advanced in this essay – that their frontal faces of

silens or nymphs are looking for other mythical creatures of their kind in the

space occupied by the viewer – is based primarily on a formal analysis of the

pictorial conception or structure that informs the decoration of the cups. Social

and historical considerations support this interpretation. Most of the vasepaintings considered here were designed, so far as one can tell, for use in the

symposium.95 A large body of Archaic Greek poetry also affords the participants

in symposia the possibility of temporarily adopting alternative identities. Those

poems consist of first-person narratives. In both ancient and modern scholarship,

the first-person form of poetic narrative has often been taken to reflect the poems’

function as autobiographical records of the lives of the poets. Two trends in

modern scholarship have modified that approach. Scholars have called into

question the status of the poetry as faithful autobiography.96 And scholars have

recognized that first-person poetic narratives were very often traditional poems,

sung by participants in symposia, sometimes for generations.97 Scholarly interest

238

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

has broadened to include the question of how poetry functioned within the

symposium, in addition to the traditional question of how poetry related to the

lives of the poets; the former question is of particular relevance to the interpretation of vase-painting that circulated in the same context. The re-performance

of first-person poetic narratives aloud, before one’s fellow symposiasts, by persons

other than the poets, introduced anachronistic, fictional, and sometimes even

purely mythical, personae into the drinking group. When a symposiast sang a

traditional first-person narrative, he necessarily adopted the first-person pronoun

of the poem, and all the experiences recounted by that voice, as his own,98 as in

the well-known poem by Archilochos: ‘Some Saian exults in my shield which I left

– a faultless weapon – beside a bush against my will. But I saved myself. What do I

care about that shield? To hell with it! I’ll get one that’s just as good another

time.’99 Thanks to the forms of the verbs or pronouns and the participatory

nature of sympotic entertainment, the symposiast who sang such a song claimed

out loud, before his companions, to be someone that he perhaps was not, or to

have had an experience that in all likelihood was something that he had never

experienced. Vase-paintings intended for use in the symposium employ the

frontal face, in some cases, for the same reason: as a structural device to elicit the

adoption of a persona by the user or viewer of a vase.

Ewen Bowie has pointed out that a poem such as Archilochos fragment 1 – ‘I

am the servant of lord Enyalios and skilled in the lovely gift of the Muses’ – might

be sung with equal relevance by any of the poet’s companions, all of whom were

familiar with war and singing.100 Other Archaic poems demand a more radical

shift in the temporary identity of any symposiast performing them, thanks to the

content, as well as the first-person structure, of their narratives. The most striking

and unambiguous examples are first-person poetic narratives that have female

narrators: ‘I am a fine, prize-winning (kal

Z kai aeyliZ) horse, but I carry a man

who is utterly base, and this causes me the greatest pain. Often I was on the point

of breaking the bit, throwing (osamenZ) my bad rider, and running off.’ (Thgn.

257–60) The feminine forms of adjectives and participle assure us that the

narrator is female, yet the poem was almost certainly intended for presentation

in a symposium, the social preserve of men. It is true that flute girls and courtesans attended symposia, but there is no evidence to suggest that they participated in the central sympotic activity of singing poetry.101 Consider also the

fragment ‘me, wretched woman (eme deilan, feminine adjective), me, sharing in

all misery . . .’, composed by Alkaios according to Hephaisteion;102 or the fragment ‘I come up from the river bringing (jerousa, feminine participle) [the

washing] all bright’, attributed to Anakreon by Hephaisteion.103 Although the

fragmentary nature of the verses prevents one from ascertaining the theme or

genre of the original poems (erotic?), neither poem seems to begin with a diegetic

introduction to the effect that ‘I, a male voice, am going to quote the speech of a

woman’; rather, the poems appear to begin emphatically in the persona of a

woman – ‘me, wretched woman’.104 Bowie concluded that: ‘taken together the

songs are better seen as evidence for male symposiasts entertaining each other by

taking on – in song at least – a female role.’105 The invitation implicit in gorgoneia,

many eye cups, and some frontal images of silens on drinking vessels, to take on

the identity of Perseus, a silen, or a nymph, seems related to the role-playing built

into much of the poetry that served as the principal form of entertainment at the

˛

˛

˛

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

239

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

symposia in which the vases were used. And the extraordinary transformations

inherent in such pictorially inspired metamorphoses – from a member of the

aristocracy in good standing to a scurrilous, half-breed silen or hippy nymph – is

parallelled by the diversity of first-person narrators in the poetry, which include

not only women but also sex maniacs and thieves.106

NIETZSCHE

Listening to a symposiast sing a traditional first-person narrative, no one mistook

the performer for the fictional character, least of all the performer himself. The

eye contact afforded by gorgoneia, eye cups and some visual representations of

figures en face facilitate the temporary augmentation of the identity of the viewer,

not its wholesale replacement. As the viewer takes up the point of view of Perseus,

a silen, or a nymph, he or she does not lose sight of his/her regular identity. That

point was developed in the earliest modern articulation of the form of spectatorship that is the subject of this paper, in Friedrich Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy

(1876).107 The Birth of Tragedy distinguishes between two different means by which

art relates to creator, audience, or viewer, a distinction between a medium oriented

towards the subjective involvement of the spectator, on the one hand, and a medium

that is concerned with making something objectively present, on the other:

[t]o see oneself transformed before one’s own eyes and to begin to act as if one had entered into

another body, another character. This process stands at the beginning of the origin of drama.

Here we have something different from the rhapsodist who does not become fused with his

images but, like a painter, sees them outside himself as objects of contemplation.108

For my purposes, The Birth of Tragedy is useful because it offers a nuanced account

of the subjectively involved experience that certain forms of early Greek poetry

afforded its audience as well as its performers. The account helps to clarify more

precisely the kind of imaginative engagement that, I believe, characterized the

experience of eye cups. As a sketch of the origins of tragedy – as an account of how

the genre came into being – Nietzsche’s book remains as problematic as it was

when it was first attacked by Wilamowitz in the late nineteenth century.109

Having lost sight of the importance of subjective involvement for the audience of theatre, Nietzsche argued, moderns have difficulty in accepting the

ancient belief that the chorus alone was the original form of Greek drama:

‘[a]ccustomed as we are to the function of our modern stage chorus, especially in

operas, we could not comprehend why the tragic chorus of the Greeks should be

older, more original and important than the ‘‘action’’ proper, as the voice of

tradition claimed unmistakably.’110 Nietzsche traced the primacy of the chorus to

a psychology of Dionysiac ritual:

the revelling throng, the votaries of Dionysus jubilate under the spell of such moods and

insights whose power transforms them before their own eyes till they imagine that they are

beholding themselves as the restored geniuses of nature, as satyrs. The later constitution of the

chorus in tragedy is the artistic imitation of this natural phenomenon.111 . . . In [Greek] theatres

the terraced structure of concentric arcs made it possible for everybody to overlook the whole

world of culture around him and to imagine, in absorbed contemplation, that he himself was a

240

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

chorist. In the light of this insight we may call the chorus in its primitive form, in proto-tragedy,

the mirror image in which the Dionysian man contemplates himself. This phenomenon is best

made clear by imagining an actor who, being truly talented, sees the role he is supposed to play

quite palpably before his eyes.112

Especially striking is the degree of self-consciousness of the votary, audience

member and actor in the experience of drama or its ritual predecessor. The

votaries do not simply become – they are not just transformed into – satyrs, losing

any sense of who they were before. The ritual experience allows them to perceive

the transformation in themselves or, to follow the complex articulation in the

text, ‘transforms them before their own eyes till they imagine that they are

beholding themselves’ as satyrs. The self-awareness of the audience is also

expressed through Nietzsche’s use of the mirror as a metaphor: in absorbed

contemplation, an audience member can imagine that he is a chorus member,

but what is revealed, as if in a mirror, is himself as someone opened up to the

aesthetic experience. In this account, the measure of true talent in acting is when

the actor is able to see himself in his role palpably before his own eyes, not (one

may speculate) the ability to lose or forget oneself completely in one’s role. The

special quality of doubleness characterizing Nietzsche’s conception of the

aesthetic experience of early drama, of simultaneously experiencing transformation and being aware of the difference between self and other, is expressed in

an essay preceding The Birth of Tragedy: ‘so must the thrall to Dionysus be intoxicated, while simultaneously lurking behind himself as an observer.’113

Not surprisingly, perhaps, the origins of the eye cup have been associated with the

development of the mask in the early history of Athenian drama.114 As I have

argued, however, the link between eye cups and drama is deeper and more

complex than just a tangible object such as a mask. And the aesthetic effect of the

eye cup is not limited to those moments when it is lifted to the face and, like a

mask, replaces the visage of a drinker. The eye cup may translate into the medium

of ceramics some of the properties of dramatic masks, but it also, like the

gorgoneion, makes use of properties unique to pictorial art to evoke the presence of

an imaginary figure with whom the viewer is invited to identify. What links the

diverse cultural forms studied in this paper – eye cups, gorgoneia, some frontal

images of silens, much sympotic poetry, and perhaps even early drama or

Dionysiac choral performance – is something essentially structural. Although the

shared aesthetic conception manifests itself concretely in quite different ways in

the different media – through the use of first-person pronouns and verb forms in

poetry, the prominence of a chorus in drama, and the role of frontality and eye

contact in vase-painting – all the works of art considered here discourage the

singer, drinker and/or spectator from contemplating the work of art or poetry

from a cool distance, and embroil them fully in the fiction.

Notes

For useful comments on a draft of this paper, I wish to thank my colleagues in

the art department at Williams College, Massachusetts. The following special

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

241

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

abbreviations are used in the notes: ABV: J.D. Beazley, Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters,

Oxford, 1956; ARV2 : Beazley, Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters, 2nd edn, Oxford, 1963;

Para: Beazley, Paralipomena: Additions to Attic Black-Figure Vase-Painters and to Attic RedFigure Vase-Painters (Second Edition), Oxford, 1971; CVA: Corpus vasorum antiquorum;

LIMC: Lexicon iconographicum mythologiae classicae; RVAp: A.D. Trendall and Alexander Cambitoglou, The Red-Figured Vases of Apulia, Oxford, 1978–82. The Beazley

archive database may be found at http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/. Abbreviations of

ancient authors and texts are after Simon Hornblower and Anthony Spawford,

eds, The Oxford Classical Dictionary, 3rd edn, Oxford, 1999.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

242

Munich 589, Andreas Rumpf, Chalkidische Vasen,

Berlin, 1927, 36, no. 244, pl. 178.

See, for example, D.A. Jackson, East Greek Influence on Attic Vases, Society for the Promotion of

Hellenic Studies, supplementary paper, no. 13,

London, 1976, 68.

For the possibility of meaning, even in some

instances of the meander pattern, see Nikolaus

.

.

Himmelmann-Wildschutz,

Uber

einige gegenst.andliche Bedeutungsmöglichkeiten des fr.uhgriechischen Ornaments, AbhMainz, no. 7, Wiesbaden,

1968.

Rainer Mack, ‘Facing down Medusa (an

aetiology of the gaze)’, Art History, 25, 2002,

571–604.

New York 98.8.25, Rumpf, Chalkidische Vasen, 38,

no. 263, pl. 187. For the Chalkidean series

generally, see Rumpf, Chalkidische Vasen, 35–9,

125–6; Jette Keck, Studien zur Rezeption fremder

Einfl.usse in der chalkidischen Keramik, Archologische Studien, vol. 8, Frankfurt am Main,

1988, 64–79. For the location of the production

centre (Chalkis or Rhegion), see Marion True,

‘The murder of Rhesos on a Chalcidian neckamphora by the Inscription Painter’, in The Ages

of Homer: A Tribute to Emily Townsend Vermeule,

eds Jane B. Carter and Sarah P. Morris, Austin,

1995, 427, n. 8.

The Athenian eye cup was studied in detail by

Jeanne Aline Jordan, Attic Black-Figured Eye-Cups,

University Microfilms International, no.

8812638, Ann Arbor, 1988.

Munich 2044, type A cup, ABV 146, 21, Erika

Simon, Max Hirmer and Albert Hirmer, Die

griechischen Vasen, 2nd edn, Munich, 1981, pl.

XXIV, 73. On the position of the cup within the

series of Athenian eye cups, see Gloria Ferrari,

‘Eye-cup’, Revue archeologique, 1986, 12; Jordan,

Eye-cups, 7–9.

Rumpf, Chalkidische Vasen, 126. On the chronology of Chalkidean cups, see also Keck, Chalkidischen Keramik, 65.

Hansjörg Bloesch, Formen attischer Schalen von

Exekias bis zum Ende des strengen Stils, Bern, 1940,

2–4.

For example, London 1888.6–1.392, Matthias

Steinhart, Das Motiv des Auges in der Griechischen

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

Bildkunst, Mainz, 1995, pl. 20,3. For various

opinions on the relationships between, or

derivations of, the different series of eye cups,

see Rumpf, Chalkidische Vasen, 125; Jackson, East

Greek Influence, 64–5; Keck, Chalkidischen Keramik,

70, 72; Norbert Kunisch, Berlin 4, CVA Germany

33, Munich, 1971, 44; Steinhart, Motiv des Auges,

62; H.R.W. Smith, The Origin of Chalkidean Ware,

University of California publications in classical archaeology, vol. 1, Berkeley, 1932, 123;

Jordan, Eye-cups, 8–9; Didier Martens, Une esthétique de la transgression: Le vase grec de la fin de

l’époque géométrique au début de l’époque classique,

Mémoire de la classe des beaux-arts, collection

in-8o, 3e série, vol. 2, Brussels, 1992, 315–16;

Ferrari, ‘Eye-cup’, 13–14.

For references, see Norbert Kunisch, ‘Die Augen

des Augenschalen’, Antike Kunst, 33, 1990, 21, n.

9; Martens, Transgression, 332–5.

Martens, Transgression, 332–47. See also J.L.

Benson, ‘The central group of the Corfu pediment’, in Gestalt und Geschichte: Festschrift K.

Schefold, Antike Kunst Beiheft 4, Bern, 1967, 48–

50. See also Alexandre G. Mitchell, ‘Humour in

Greek vase-painting’, Revue archeologique, 2004,

7.

Kunisch, ‘Augen’, 20.

W.L. Hildburgh, ‘Apotropaism in Greek vasepaintings’, Folklore, 57–8, 1946-47, 158.

For the latest eye cups, see Dyfri Williams, ‘The

late archaic class of eye-cups’, in Proceedings of

the Third Symposium on Ancient Greek and Related

Pottery, eds Jette Christiansen and Torben

Melander, Copenhagen, 1988, 675–83.

See Ferrari, ‘Eye-cup’, 11.

On this point, see Anna Collinge, ‘A ‘‘Chalkidean’’ cup restored’, Arch.aologischer Anzeiger,

1984, 567; Keck, Chalkidischen Keramik, 70;

Steinhart, Motiv des Auges, 55.

Munich N. I. 8760, plate, Para 46, Lydos, LIMC, 4,

pl. 165 Gorgo, Gorgones 38. A survey of the

motif appears in Ingrid Krauskopf and StefanChristian Dahlinger, ‘Gorgo, Gorgones’, LIMC,

4, 1988, 285–330.

J.D. Beazley, The Development of Attic Black-Figure,

eds Dietrich von Bothmer and Mary B. Moore,

Berkeley, 1986, 62.

& ASSOCIATION OF ART HISTORIANS 2007

I N V O L V E D S P E C TAT O R S H I P I N A R C H A I C G R E E K A R T

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

J.D. Beazley and Filippo Magi, La raccolta Benedetto Guglielmi nel museo gregoriano etrusco,

Vatican City, 1939, 58.

Beazley and Magi, La raccolta Benedetto

Guglielmo, 57.

Compare Martens, Transgression, 348–51.

Madrid inv. 1999/99/72, Paloma Cabrera Bonet,

ed., La colección várez fisa en el museo arqueológico

nacional, Madrid, 2003, 217–19, no.73. Compare