Air Quality Assessment 2008 Technical

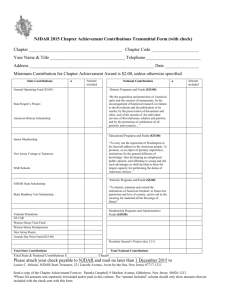

advertisement