PERSUASION AND MANIPULATION: RELEVANCE ACROSS MULTIPLE AUDIENCES by Kevin Sparks

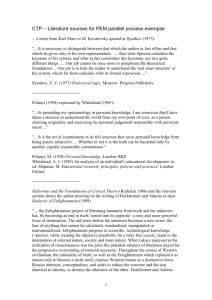

advertisement