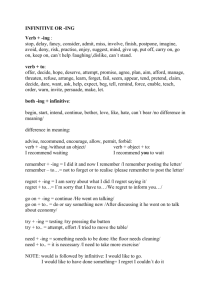

-ING by Joëlle C. Lewis

advertisement