POSITIVE ORIENTATION TOWARDS THE VERNACULAR AMONG THE TALYSH OF SUMGAYIT by

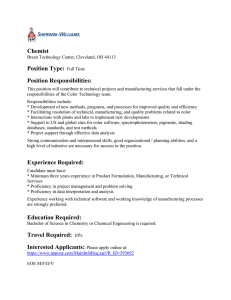

advertisement