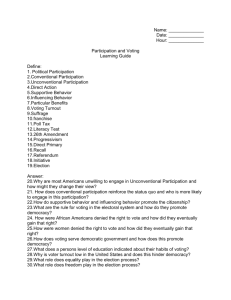

E-voting in the United States: A cautionary tale

advertisement

E-voting in the United States: A cautionary tale A presentation to the Workshop on Electronic Government and Electronic Voting, given at the National e-Science Centre, Edinburgh, 27th February 2006 By Andrew Gumbel I wanted to start this talk with an anecdote that would encapsulate the current problems of electronic voting in the United States. Perhaps inevitably, I found myself settling on a story from Florida. Florida is far from the only U.S. state with a reputation for dodgy electoral practices, but it is the place where the dysfunctions were first brought glaringly to public attention thanks to the protracted struggle between Al Gore and George W Bush for the state’s decisive 25 electoral votes in the 2000 presidential election. I’m sure you remember some of the details of that excruciating 36-day showdown: the infamous butterfly ballot in Palm Beach County, which proved so confusing that thousands of elderly Jewish voters belatedly discovered that they had voted for Pat Buchanan, a candidate they regarded as rabidly anti-Semitic; the manoeuvrings and barely concealed partisan prejudice of Katherine Harris, the Florida secretary of state who was both the arbiter of the election and also the co-chair of George Bush’s Florida campaign; and, of course, the inner workings of the Votomatic punch card machine, on which we all became instant experts thanks to television images of county officials staring through magnifying glasses at cardboard ballots whose detachable pieces – or chad -- had been left merely hanging, bulging or just barely dimpled. You are going to hear a whole lot more about Florida over the course of this presentation, but for now I want you to imagine a scene in the state capital, Tallahassee, from last December. The supervisor of elections in Leon County, which includes Tallahassee, is a man called Ion Sancho, and he is one of the best, most conscientious voting officials in the United States – one of the few who actually believes the process should be as open and accountable to the voters as possible. He also had the courage to invite a Finnish computer specialist called Harri Hursti to test Hursti’s claim that he had found a way of breaking with the county’s vote tabulation software in such a way as to change the outcome of any given vote without leaving any detectable trace. The system Hursti claimed to be able to circumvent was made by Diebold Election Systems, one of the leading manufacturers of voting equipment in the United States. Diebold’s tabulation software is used with both electronic touch screen voting systems, the most controversial of the new generation of voting machines in the United States, and also with optical scan machinery that reads hand-marked paper ballots. That’s the type of system deployed by Ion Sancho in Leon County. Harri Hursti has been somewhat vague about his hacking methodology, not least for security reasons, but we do know it involves 1 making changes to the memory card used to count up the votes on each optical scan reader with the aid of a commercially available agricultural scanning device. Anyway, last December, Sancho and seven other people gathered in a warehouse a few blocks from county election headquarters and held a little trial election. The question on the ballot, appropriately, was: “Can the votes of this Diebold system be hacked using the memory card?” Two people voted yes and the other six voted no. Their ballots were fed into the optical scan reader and transmitted to a tabulation device. The result then popped up: seven votes for yes, and just one vote for no. Supervisor Sancho immediately recognised the profound implications of this experiment. A disgruntled county employee or political operative with access to the voting machinery could fiddle with the results of an election and the election supervisor might never know. He has since ditched his Diebold system and is switching to another company. One might have thought the rest of the country would have followed suit, but that has been very far from the case. Diebold itself has proved entirely unapologetic and has even intimated in a lawyer’s letter that any security risks have been incurred by Sancho himself. The Florida secretary of state – no longer Katherine Harris, who has gone on to bigger and better things – has been similarly unperturbed by Hursti’s exposure of the security breach, saying only that if Ion Sancho has a problem with his Diebold machinery, that is something for him to sort out with Diebold. The fact that several other Florida counties are also Diebold clients and show no inclination to follow Sancho’s lead in dropping the company has been of absolutely no concern. This is something U.S. election officials do a lot when confronted with a seemingly intractable problem – delegate it down down to the next level of responsibility and hope it goes away. On the other side of the country, California’s top voting official spent several months last year considering whether to invite Hursti to try to hack into his state’s own Diebold voting equipment, in particular a new model touch screen called the TSx whose certification had been held up for three years because of gaping technical flaws and a documented history of Diebold lying about the machine’s state of readiness. Unaccountably, in the wake of the experiment in Leon County, Secretary of State Bruce McPherson’s decided to drop the idea of bringing in Hursti. Earlier this month, his own technical advisory panel warned him, based on its own analysis, that the memory cards were vulnerable to undetectable hack attacks. The panel found 16 different software problems that could permit hackers to “change vote totals, modify reports, change the names of candidates, change the races being voted” and even crash the machines altogether without so much as the need for a password. Three days after that report was issued, though, McPherson decided to allow the TSx to be used in this year’s mid-term elections, rationalising the problems as “manageable”. 2 From the perspective of this side of the Atlantic, all this must seem insane. By any measure of how one might responsibly develop and introduce electronic voting systems, it IS insane. The champions of e-voting in the United States would have us believe that the computerized machines represent a revolutionary leap forward in a country notoriously beleaguered by electoral corruption and cheating in the past. The machines are user-friendly, they argue, and function both flawlessly and at lightning speed – what is not to like? Unfortunately, this is little better than a fairy-tale version of what has really occurred, which is that private companies of dubious reputation have been allowed to go round, county by county, and sell machines that have been inadequately inspected if they have been inspected at all, are never publicly tested beyond a rudimentary pre-election exercise that does not come close to replicating the complexities of a typical multi-race election, and are virtually immune from closer scrutiny in case of questions about their proper functioning in a live election because their software is protected as a trade secret under U.S. law. I want to lay out some of the history of how e-voting has evolved in the United States, but first it’s worth pointing out a couple of things that make the conduct of U.S. elections both unique and uniquely dysfunctional among the world’s mature democracies. Ever since the first big push towards universal suffrage in the 1820s and 1830s, the system has been far too susceptible to the partisan interests of the major parties. In contrast to many European countries, or Canada or Australia, successive waves of reform in the 19th century failed to create a reliably honest class of election administrators, or even a reliable system of uniform rules by which they might be expected to operate. The United States has no central electoral commission or equivalent body, and Congress has absolutely no oversight over election rules or election machinery. Most decisions on election administration are made at county level, and since there are more than 4000 counties in the United States, the country effectively has more than 4000 electoral systems. Historically, the Republicans and Democrats have liked it this way, because it has given them scope to control the process in counties where they are predominant and, in certain circumstances, to sway the outcome of the vote. Election administration has been notoriously shoddy for as long as anyone can remember. In 1930, a report for the Brookings Institution in Washington found: “There is probably no other phase of public administration in the United States which is so badly managed as the conduct of elections….The truth of the matter is that the whole administration – organizations, laws, methods and procedures, and records – are, for most states, quite obsolete.” The culture has not changed significantly since – as attested by the long list of people indicted and sentenced on election fraud and embezzlement charges over the decades. Sometimes it is county officials who are indicted, and sometimes it is the representatives of voting machine manufacturers. Quite often, one party saves his skin by ratting out the other. Quite a few of them stay in the business even after they’ve been through the legal wringer. The other general observation I want to make is that, for the past hundred years, reformers in the United States have repeatedly made the mistake of thinking that what is needed to fix the electoral system is the right kind of voting machine. In my book I call this the fallacy of the technological fix. It’s a fallacy because the problem in the United 3 States is not and never has been the technology of voting; the problem is rather the nature of the two-party political system and the peculiarly elemental, vicious manner in which electoral contests are fought. Florida in 2000 was a classic example of the fallacy. Conventional wisdom at the time wanted to blame everything on the punch card machines, but the principal cause of the meltdown was the sheer determination of the Florida Republican Party, which controlled most of the key offices and most of the county governments in the state. Governor Jeb Bush wanted to make sure his brother George W. became the next president, no matter what. Even with lousy machines, there is no excuse for not recounting every vote. Every new generation of machine has been hailed as the miracle that will at last make elections fraud- and foolproof, and every time the initial optimism has given way to disappointment. That was true of the big, bulky lever machines first introduced in the 1890s, which were so disliked by the voters that 15 of the first 24 states to purchase them decided to ditch them again. If the lever machines returned in the 1930s and onwards, it was primarily because they made life easier for the election officials and, in some instances, for the corrupt politicians who understood how they could be used to throw the outcome of important close races. Earl Long, the notoriously corrupt governor of Louisiana in the 1950s, once boasted that with the right board of commissioners he could get his lever machines to sing “Home Sweet Home”. The Votomatic punch card machines that caused so much trouble in Florida were also greeted as a miracle in the early 1960s; one voting official in Georgia declared excitedly that deploying them was “as simple as stirring coffee with a spoon”. The Votomatic was the first machine in the United States to use electronic tabulation. And, within six years of its first deployment in 1964, some serious questions began to asked about the reliability of that tabulation software. A study commissioned by the city of St Louis in 1970 found that punchcard balloting was “more easily subject to abuse” than lever machines, because there was no way of making sure the counters had been set to read the cards correctly. “It is possible to write a program in such a way that no test can be made to assure that the program works the way it is supposed to work,” the accounting firm Price Waterhouse reported. “It is possible to have instructions in computer memory to call in special procedures from core, tape, or disk files to create results other than those anticipated.” The machinery suffered a number of breakdowns both big and small over the next several years, including one election in San Antonio, Texas in 1980 when the number of voters was mysteriously adjusted downwards by six-hundredths of a per cent between election night and the date of the official canvass. This led the San Antonio Express newspaper to suggest a wry new slogan for the universal suffrage movement: “One man, 0.9984 vote.” That same year, a withering critique of the Votomatic was penned by Michael Shamos, the Pennsylvania state voting equipment examiner, who ripped the system to shreds without even mentioning the chad problem that was to play such a prominent role in Florida in 2000. Not only were punch cards laughably passé in the computer industry, 4 Shamos wrote, but the machinery was cumbersome, easily prone to tampering and a security “nightmare”. Among other things, Shamos showed how arbitrary numbers could be entered into the machines’ counters, and also how an election fixer could change the vote totals by slipping in a rogue programming card – a sort of super-punch card that would superficially look not much different from an ordinary ballot. Shamos also pinpointed an enduring problem with the way computer voting equipment was bought and sold: the fact that systems are certified for use without any public authority having access to the programming software. “It is a complete mystery to me how a program can be ‘submitted’ for certification unless the examiners are permitted to inspect it,” Shamos wrote. In the 1980s, there was no requirement even to submit the software to a private testing lab, much less make it available to county and state authorities in case of operational controversy. Deborah Seiler, the head of California’s elections division who would later become a sales rep for Diebold, told the New York Times in 1985 that she had certified a number of systems without inspecting anything. “At this point,” she said, “we don’t have the capability or the standards to certify software, and I am not aware of any state that does.” Already at this early stage, voting rights campaigners were beginning to fret about the degree of public control being signed away to private vendor companies, an issue that remains equally pressing today. Not only did the manufacturers shroud their products in secrecy, they also became actively involved in running elections, because technophobic administrators in many places thought having them around would help prevent mistakes. That did not change when the Federal Election Commission finally published some minimal standards for electronic voting in 1990. As Mae Churchill of the Urban Policy Research Institute in California wrote to the FEC at the time: “The proprietary interests of voting system vendors have been allowed to drive the standards drafting procedure… The privatizing of elections is taking place without the consent or knowledge of the governed.” Two very dodgy elections in the 1980s highlighted some of the concerns about electronic voting systems. The first was a congressional election in Kanawha County, West Virginia, 1980. The powerful incumbent Democratic congressman, John Hutchinson, had been expected to trounce his Republican opponent by a double-digit margin. But the Republican, Mick Staton, was oddly confident that the polls were wrong and that he would finish ahead by five points. There was an inherent conflict of interest in the management of the race, since the county clerk was not only a Republican but was married to Staton’s single largest campaign contributor. Then, on election night, a young Republican state legislator called Walter Price saw some very odd things going on in the count room. According to an account he later gave under oath, Peggy Miller, the county clerk, got down on her knees four times during the night and, as she consulted notes on a clipboard, turned a key on the master computer, flipped some switches and turned the key back again. Price also saw Miller’s husband Steve enter the computer “cage”, pull a pack of what looked like computer punchcards out of his suit jacket and hand them to his wife. Peggy Miller ran these through the card reader, retrieved them, then handed them back to her husband. 5 When Staton was declared the winner by a five-point margin, exactly as he had predicted, Price became convinced he had been a witness to vote fraud and, despite his party affiliation, resolved to denounce it publicly. The Millers denied everything and, despite the legal challenge filed almost immediately against Staton, arranged for all materials relating to the election to be destroyed as soon as the West Virginia statutes allowed. In the absence of physical evidence, the prosecution never stood much chance, and the charges were eventually thrown out. The other dubious election took place in Florida in 1988, when the Democratic candidate for Senate, Buddy MacKay, was projected on election night to be the winner but ended up trailing his Republican rival, Connie Mack, by 34,500 votes out of more than 4 million. The odd thing here was that in four of state’s most heavily populated, most Democratic counties – covering Miami, Tampa, West Palm Beach and Sarasota – the drop-off between the number of people recording a vote for President and those voting for the Senate was a staggering, and utterly anomalous, 20 per cent. Translated into voter numbers, that meant as many as 200,000 votes entrusted to Votomatic punchcard machines vanished into the ether, votes that most likely would have broken heavily in MacKay’s favor. Election officials suggested that voters overlooked the Senate race because it was squeezed onto the bottom of the first page, beneath the list of candidates for President. That explanation did not hold, however, because a number of counties had the same ballot design but not the same problem. While Tampa had a dropoff rate of 25 per cent between the presidential and Senate race, next-door St Petersburg’s drop-off rate, with the same ballot, was just 1 per cent. MacKay, for one, became convinced the election had been stolen, and even did some research to figure out how – speculating that the machine could have been programmed, say, to miscount every tenth vote. One leading computer scientist, Peter Neumann of SRI International in California, confirmed that MacKay’s hunch was entirely plausible. “Remembering that these computer systems reportedly permit operators to turn off the audit trails and to change arbitrary memory locations on the fly,” he wrote about the Mack-MacKay race, “it seems natural to wonder whether anything fishy went on.” MacKay pressed to have the ballots examined and recounted, but under Florida law at the time recounts were left to the discretion of county canvassing boards. They all turned him down flat, on the grounds that he had no concrete evidence to establish a pattern of foul play. “It’s a real Catch-22 situation,” MacKay said. “You’ve got to show fraud to get a manual recount, but without a manual recount you can’t prove fraud.” Barely a month after the Mack-MacKay election, a company very interested in protecting the interests of electronic voting made a remarkable offer which it hoped would protect its evolving technology from the suspicion of foul play. The company was called Shoup, and it had been in the voting machine business from the very beginning – not always with a reputation for scrupulous honesty, to put it mildly. But Shoup didn’t want doubts about the Florida election to spoil the marketing of its Shouptronic, one of the first Direct Recording Electronic, or DRE, machines to be put into operation. So Shoup’s chief engineer, Robert Boram, wrote to the FEC’s Voting Equipment Standards 6 Advisory Committee to announce that the Shouptronic’s source code would henceforth be available for outside review. “The public interest served by securing public confidence in direct electronic voting systems takes precedence over the remote possibility that some competitor might gain access to our source code and thereby enhance their product’s marketability,” Boram wrote. “We would hope all vendors of all election systems using any form of computers would now open their source codes to outside review. Let’s put to rest the concerns raised as to the degree of reliability and integrity of computerized voting systems.” It’s a pity Boram’s sentiments weren’t echoed a decade later, when the DRE craze really took off. Back in the late 1980s, the technology was still too new, and the motivation to switch systems too lackluster, for his idea to take hold. Boram was refreshingly honest all round when it came to the realities of computer voting. He told a newspaper reporter in 1992 exactly why it was a mistake to rely on the internal audit mechanism of a DRE as opposed to an independently verifiable paper trail. “I could write a routine inside the system that not only changes the election outcome,” he said, “but also changes the images to conform to it.” If that wasn’t warning enough, election administrators should have paid attention to a lecture a few years earlier given by the computer scientist Ken Thompson, in which he demonstrated that a bug could be introduced into computer software independent of the source code. “The moral is obvious,” he concluded. “You can’t trust code that you did not totally create yourself… No amount of source-level verification or scrutiny will protect you from using untrusted code… A well installed microcode bug will be almost impossible to detect.” Such warnings went entirely unheeded, however. By the time of the 2000 election, the first touch screen DREs had been deployed, most notably in Riverside County, California, where the local registrar of voters, Mischelle Townsend, wasted little time gloating over the punch card mess in Florida. By her account, election night in Riverside had been “flawless” – a word of which she became inordinately fond over the next few years – and much of the rest of the country was inclined to believe her. Wired News, the journal of record of the then booming high-tech industry, initially touted her as some kind of prophet for the new millennium. In reality, though, election night in Riverside had been a near disaster. A couple of hours after the polls closed, the tabulation software overloaded and started deleting votes from the tallying system instead of adding them. The vendor company, Sequoia Pacific, had to send in an emergency resuscitation team, creating a delay of several hours. The system was eventually righted, at least according to Sequoia, but Riverside’s results were not published until two hours after neighboring San Bernardino County, then still using punch cards. In a down-ticket for a local school board, one candidate had been comfortably in winning position when the machines went down – and was reported as such in the next day’s Riverside Press Enterprise newspaper – only to find herself trailing when the count resumed, for no reason she could easily ascertain. Her demands for a full explanation met only with official intransigence. Townsend reacted to the setbacks simply by pretending they had not happened. 7 Her ruse worked, and soon many other counties wanted to follow her example. Theresa LePore, the architect of the infamous butterfly ballot in Palm Beach County, Florida, quickly persuaded her county commissioners to spend $14.4 million on their own Sequoia system. The new touchscreens were deployed in time for the March 2002 local elections and they, too, failed at the first hurdle. A well-respected former mayor of Boca Raton called Emil Danciu was flabbergasted to discover he had finished third in a race for a seat on the Boca Raton city council, since an opinion poll taken shortly before the election had put him seventeen points in the lead. Supporters began flooding his campaign office with stories that every time they tried to vote for him, the machine lit up the name of one of his opponents instead. Danciu also discovered that fifteen cartridges containing the vote totals from machines in his home precinct had been removed by a poll worker on election night, causing an unexpected delay in the final results. Some of the cartridges were subsequently found to be empty, for reasons that have never been adequately explained. Armed with a fistful of affidavits, Danciu sued for access to the Sequoia source code to see if it did not contain some fatal flaw. He was told, however, that the source code was considered a trade secret under Florida law, and that even LePore and her staff were not authorized to examine it on pain of criminal prosecution. His suit was thus thrown out, and he decided it would be futile even to appeal. Two weeks after the Danciu election, something even stranger happened. In the inland town of Wellington, a run-off election for mayor was decided by just four votes. Another seventy-eight votes, however, did not register on the machines at all. Since the run-off was the only race on the ballot, that meant – assuming for a moment the machines were not lying – that seventy-eight people had jumped in their cars, driven to the polls, not voted, and gone home again. The scenario beggared belief, but it was touted, with an absolutely straight face, by LePore. The response to the 2000 presidential fiasco was off to an unpromising start, to put it mildly. And it only got worse. In 12 of southern Florida’s most densely populated counties, officials were induced to buy a touch screen DRE system made by Election Systems and Software, or ES&S, the company that had previously operated the Votomatic punch card machines. ES&S’s DRE, the iVotronic, was still in development, but that inconvenient fact was hushed up, not least thanks to the efforts of Katherine Harris’s predecessor as secretary of state, Sandra Mortham, who found herself in the happy position of being chief lobbyist for both the Florida Association of Counties and ES&S itself. In other words, all she had to do was sell herself on the deal, and she picked up commissions from both ends. Disaster quickly ensued in Miami-Dade County, where ES&S had promised to add a third language, Creole, on top of English and Spanish, which were standard features. The company omitted to mention that the trilingual package would have be loaded separately via a dedicated flashcard that would drastically slow down each machine. When the iVotronics made their debut in the Democratic governor’s race primary in September 2002, they took so long to boot up the entire electoral machinery of Miami-Dade county ground to a halt. Many polling stations did not open until lunchtime, creating consternation from one end of the county to the other. To make matters worse, freak storms knocked out power to certain precincts for so long that the battery back-up on 8 many iVotronics ran out. Then, the tabulation machines went bananas. One Miami precinct reported 900 per cent turnout; another showed just one ballot cast out of 1,637 registered voters. Jeb Bush, the governor, was forced to declare a state of emergency in both MiamiDade and neighbouring Broward County, which had experienced similar problems, and extended the opening hours of polling stations by two hours. Lida Rodriguez-Taseff, a gutsy lawyer who founded the Miami-Dade Electoral Reform Coalition and quickly became a major thorn in ES&S’s side, remarked bitterly: “This was an invention that had never been tested. We were the guinea pigs.” The introduction of e-voting systems was equally troubled in other parts of the country, if not necessarily for the same reasons. Both Maryland and Georgia rushed into statewide buys of Diebold DREs in time for the 2002 election cycle, blithely ignoring advice from their own technical experts that the system was not read for prime time. Tom Iler, the information technology chief in Baltimore County, Maryland, protested vigorously, but to no avail. As he later commented to me: “You don’t want to be on the bleeding edge with critical systems… Why would anyone want to buy first-generation technology which is a lot more expensive than established technology, just to see it become obsolete very quickly?” In Georgia, just a few weeks after the Diebold purchase was approved, the voting terminals began demonstrating symptoms of serious malfunction. Rob Behler, an engineer working as a Diebold contractor at the company’s Georgia warehouse, later reported that 25-30 per cent of the machines were either crashing as they were being booted up or otherwise failing. In his account, which the company has never denied, Diebold came up with three successive software patches – one in June, one in July and one in August – to remedy the problem. The booting problem was solved by the time of the November election, but it appears that the patches were never submitted for certification – a basic requirement under state and federal law. On election day, the state had its share of machine malfunction – terminals freezing, screen alignments going out of whack, and so on. Most troublesome, however, were the results of the races for Governor and U.S. Senate, which suggested wild double-digit swings in favor of the Republican candidates from the final pre-election opinion polls. Sonny Perdue became the first Republican Governor to be elected in 144 years thanks to a sixteen point swing away from the Democratic incumbent, Roy Barnes. And Saxby Chambliss, the colorless Republican Senate candidate, pulled off an upset victory against the popular Vietnam War veteran Max Cleland, representing a nine-to-twelve point swing. Were these statistical anomalies, or was something fishier going on? In the absence of a paper backup, or of any hint of transparency from state officials, the question was for the most part unanswerable. As it later became clear, there were two fundamental problems with the touchscreen DREs. One was their vulnerability to software bugs, malicious code or hack attacks, as Ken Thompson and others had been warning for years. The other was that they were poorly programmed by their manufacturers and inadequately tested by government- 9 contracted laboratories charged with their certification. This was a well-kept dirty secret at the outset, making it all the easier for vendors to blindside political decision-makers with grandiose claims about the machines’ miracle-working powers. Because of the proprietary nature of the software, state and county officials had to take assurances about security almost entirely on trust. And take those assurances they did – because they badly wanted to believe in the new machines. But it did not take long for their flaws to start causing some serious embarrassment. In early 2003, the source code for the Diebold system was left lying around on an open FTP site and discovered by a voting rights activist in Washington state. She, in turn, arranged for the material to be posted on a website in New Zealand, where it was outside the remit of U.S. trade protection laws, and opened the way for a team of top computer scientists to examine the code. That team, led by Avi Rubin of Johns Hopkins University, tore through the code in one frenzied week and was left little short of stunned by what they found. Rubin and two of his graduate students discovered within half an hour that the password unlocking the system’s encrypted data was written directly into the source code. Not only did this mean that anyone with access to the source code had the means to break into the system at will. It also meant that every single Diebold machine was crackable by exactly the same means. As David Jefferson, an elections security expert at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, later put it: “What [Diebold] did is create a big complex building, put locks on every door, use the same key for every lock, and then publish a picture of the key on the wall.” The full Hopkins/Rice report elaborated: “Cryptography, when used at all, is used incorrectly. In many places where cryptography would seem obvious and necessary, none is used. More generally, we see no evidence of disciplined software engineering processes… We also saw no evidence of any change-control process that might restrict a developer’s ability to insert arbitrary patches to the code. Absent such processes, a malevolent developer could easily make changes to the code that would create vulnerabilities to be later exploited on Election Day.” It was relatively straightforward, for example, to produce home-made replicas of the system’s voter smart cards and use them to cast multiple ballots. Insecurities in the data transmission system were potentially even more dangerous, especially if election results were sent by modem from the precinct to county headquarters. “Even unsophisticated attackers,” the report said, “can perform untraceable ‘man-in-the-middle’ attacks.” Diebold was left floundering by the report, as were the testing labs which had passed the software for federal certification. These labs were nominally independent, but in practice they had at least a financial interest in being solicitous toward the voting machine companies, since they were paid directly for their services and competed with each other for the work. All three operated under conditions of strict secrecy, which had the undeniable benefit of keeping sensitive software away from prying eyes but also made it impossible, barring leaks or court orders, to make even a minimal assessment of the labs’ competence. When Congress first mandated the Federal Election Commission to draw up minimum technical standards for electronic voting machines in the late 1980s it omitted to give any direction on how those standards should be tested and enforced. This 10 gaping administrative hole was eventually filled by the Election Center, a Houston-based non-partisan lobbying group representing state and local elections officials, which took it upon itself to accredit and oversee the labs, known as Independent Test Authorities, or ITAs. But the Election Center never wielded any formal congressional authority, giving rise to a deeply unsatisfactory situation in which the integrity of the country’s election machinery depended on a system that was both impenetrable and publicly unaccountable. Things grew only murkier as the FEC’s original 1990 standards were rendered obsolete by giant leaps forward in computer technology. Starting in late 1998, the FEC began developing a new set of standards to take account of the rise of the Internet, the growing sophistication of code-writing languages and encryption techniques, the proliferation of computer worms and viruses and other security liabilities. But when the new standards were published in 2002, the terms of their adoption became shrouded in ambiguity, not least because state and county agencies across the country were in the throes of a DRE-buying frenzy. No vendor wanted to review its entire product line while sales were so buoyant, and no elections official wanted to be left empty-handed for months on end after throwing tens of millions of dollars at a system that was supposed to be flawless anyway. So the Election Center and NASED, the National Association of State Election Directors, decided to fudge it. Any new product components, they said, would have to conform to the 2002 standards, but vendor companies would not be required to update entire systems from top to bottom. The question of what constituted a new product component was left distinctly vague. Did a patch on a software program qualify, for instance, or only a brand new software package? According to an official who helped draw up the FEC standards, the understanding was that the testing labs would have “a bit of leeway” to decide such questions for themselves. The practical consequence of that leeway has been that even now, in 2006, key components of computer voting systems are still meeting only the 1990 standards. The WinEDS program used in Sequoia’s tabulation software, for example, is still widely used, even though it is written in Visual Basic, a language known for its vulnerability to viruswriters. Had the 2002 standards been fully implemented, Sequoia would have been obliged to rewrite the program or scrap it. Perhaps the biggest problem with the whole set-up is how cozy the key players are with each other. The Election Center represents state and county officials who are clients of the machine vendors, and it also accredits testing labs who are clients of the machine vendors. If that isn’t already too close enough for comfort, the Center has also developed its own direct relationship with the vendors. In 2004, a tax filing surfaced showing that the Center had received annual donations of $10,000 from Sequoia over a four-year period. The Center’s executive director, R. Doug Lewis, acknowledged the payments, saying he had received other donations from ES&S and “probably” from Diebold as well. He didn’t show any sign of embarrassment about these ties; indeed, his organization appeared to be proud of them. At a national conference of county registrars organized in Washington in August 2004, the Election Center laid on a welcome reception sponsored by Diebold, a graduation luncheon and awards ceremony sponsored by ES&S and a dinner cruise on the Potomac and “monuments by night” tour co-sponsored by Sequoia. 11 Little wonder, given such clamorous conflicts of interest, if the system has failed so spectacularly. When the Hopkins/Rice report first came out, the man in charge of examining voting machinery in Iowa, a University of Iowa computer science professor called Doug Jones, was stunned to read about some of the encryption problems because he had found exactly the same flaws when he inspected the software as far back as 1996. In those days the company was still called I-Mark Systems, not Diebold, but the software architecture was one and the same. Jones had forwarded his discoveries to both I-Mark and the testing authority, Wyle Laboratories, believing that the software as it stood should not be allowed to come to market. But his concerns were ignored. In its certification report, Wyle went so far as to write: “This is the best voting system software we’ve ever seen.” More critical reports followed on from the one led by Avi Rubin, many of them commissioned by the states themselves. Maryland commissioned two. The first, by the computer risk assessment company SAIC International, identified three hundred and twenty-eight security weaknesses, twenty-six of them critical, plus a whole slew of other high-risk issues that would arise if the system were ever hooked up to a network. The second, conducted by several former members of the National Security Agency now working for a private consultancy, Raba Technologies, included a “Red Team” exercise to try to break into the system during a simulated election. Raba found that it took approximately twenty seconds to pick the two locks securing each of Maryland’s 16,0000 AccuVote-TS terminals, and that every one of the locks – 32,000 in all – was identical. “We could have done anything we wanted to,” one of the Red Team members, computer scientist William Arbaugh of the University of Maryland, said. “We could change the ballots [before the election] or change the votes during the election.” Another team member concurred: “Diebold basically had no interest in putting actual security in this system… It’s not like they did it wrong. It’s like they didn’t bother.” Amazingly, both Diebold and Linda Lamone, the state’s top elections official, took the Raba report as a vindication. That was because, in response to the question of whether the state could deploy the system for the March 2004 primary election, the report concluded that it could, albeit unsatisfactorily, as long as a number of mitigating steps were taken to address the security holes. The report made clear this was not a long-term solution, and urged further far-reaching corrective steps. Such misgivings were entirely absent, however, from the public statements given by Lamone or Diebold’s chief executive Bob Urosevich, who said Raba had confirmed “the accuracy and security of our voting systems as they exist today”. Far from being called on their remarks, Lamone and Urosevich set the tone for elections officials across the country who faced similar criticism over their e-voting systems. The attitude was: sweat out the crisis and, if necessary, deny the problem exists. Deny that security is an issue. Deny that any machine has ever been hooked up to a network. Insist that the software has been extensively tested in government laboratories, that DREs are “100 per cent accurate”, that elections involving them have always been “flawless”. Argue that those who want a voter-verified paper trail don’t appreciate the fact that a paper trail already exists, in the form of internal audit logs and other redundant 12 data stored in the machines. Point out that touchscreens are popular with voters, and are an essential tool for compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act. In fact, insinuate that e-voting critics, aside from being conspiratorial scaremongers, are also fundamentally hostile to the interests of paraplegics, the deaf, the dumb or the blind. In short: take all the high emotion inherent in the accusation that American democracy is being undermined, and throw it right back in the faces of the accusers. That PR approach helped election officials muddle through the 2004 presidential election, if just barely in key battleground states like Ohio where foul play and underhand tactics were once again in evidence from the Republican Party which enjoyed political dominance in the state. DREs were used to count around 30 per cent of the vote in the Bush-Kerry election and although there were plenty of reports of deeply disturbing problems on a county by county basis – including one county in North Carolina which lost around 4,500 votes because of a tabulation software error -- they were given relatively little national publicity. If the Ohio vote had been as close as Florida four years earlier, one suspects the level of scrutiny would have been much higher. The PR approach in defence of electronic systems still holds today, even in the face of mounting disquiet about the safety and cost of America’s new voting systems. There have been pockets of resistance – most notably in California, which was the first of about 25 states to mandate an independently verifiable paper trail on its touch screen systems and called Diebold’s bluff on the development of its TSx model for three years – until the recent, highly questionable certification approval by Secretary of State Bruce McPherson. The federal government, meanwhile, came up with a lot of new rules and the promise of almost $4 billion in hard cash with the passage of the 2002 Help America Vote Act, some of which have made a material difference for the better. Provisional voting, for example, was an option in Florida in 2000; now it is mandatory everywhere, meaning that anyone initially found to be missing from the voter rolls can vote anyway and have his or her eligibility verified later. But the Act left a lot of the decisions on how to implement its modest reform program up to the states, which has led in turn to a lot of confusion and political manoevuring over the way in which provisional voting, for instance, should be organized. When it comes to electronic tabulation – covering optically scanned paper ballots as well as touch screens and other DREs – the Act failed to insist on a mandatory random manual recount of a small percentage of the ballots to verify that the tabulation software is working correctly. That’s a huge flaw in the system, as Harri Hursti’s hack attack experiment revealed. More generally, the Help America Vote Act did little or nothing to streamline voting practices and standards across jurisdictions. The Act established a new federal oversight body called the Election Assistance Commission. But the promised funding for the EAC did not materialise in a timely manner, leaving the body cash-strapped and near-helpless ahead of the 2004 presidential election and scarcely better off since. Last year, the EAC published a list of guidelines for the development and deployment of e-voting systems, which proved to be almost entirely useless. Not only had these systems largely been developed and sold already; the guidelines were also strictly voluntary, which meant counties and vendor companies could blithely ignore what few restrictions they imposed. 13 All of this has left voting reform advocates in the United States distinctly glum. Much of what I have laid out for you has not penetrated public debate to any great degree, for the rather sickeningly blinkered reason that any and all complaints about the electoral system have been interpreted through a partisan political prism. That is to say, the Republicans – who have dominated the past few election cycles -- have interpreted any criticisms as sour grapes by unsuccessful Democratic candidates and their supporters. Some grassroots Democrats, for their part, have made the mistake of accusing the Republicans of entering into a conspiracy with the voting machine companies to keep themselves in power indefinitely. The accusation is a mistake for two reasons – one because I don’t think it can be sustained by the facts, and two because it only perpetuates the partisan view of what should be an issue of deep concern to voters of any political persuasion. The partisan wrangling is also a more general evasion – an excuse for sympathisers of both parties to fail to recognise that the problem with the American electoral system is, and always has been, the corruption of the two-party system in and of itself. Over the past 30 years, that system has only deterioriated under the growing influence of corporate money, which has all but squeezed out meaningful policy debate in the run-up to elections and replaced it with a barrage of television advertising in which he who has the deepest pockets most often wins. As the comedian and now independent candidate for governor of Texas, Kinky Friedman, recently put it with his trademark caustic wit: in the United States, “a fool and his money are soon elected”. E-voting systems have been subject to the same systemic corruption: voting machine vendors sweet-talk underappreciated county election officials one by one, promise them the moon and then co-opt them into covering up the fact that they can’t deliver it. The problem is not necessarily with e-voting itself. One could, for exampl,e establish a national agency to impose rigorous standards and a much greater degree of uniformity on local decision-makers. Or one could, like Australia, develop an open source code that everyone would have the right to inspect and comment on. The problem, rather, is a political one. The United States has once again shown itself to be a trail-blazer and an example to the world. Only, in this case, the example it has set is how not to go about the computerisation of the mechanism at the heart of its democracy. 14