Proceedings of World Business, Finance and Management Conference

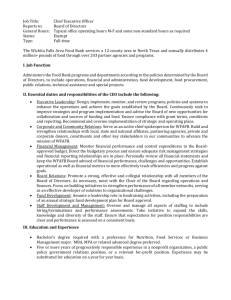

advertisement