Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference

advertisement

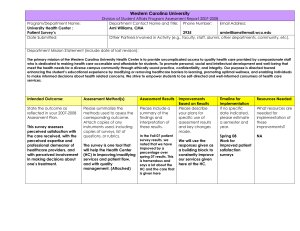

Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Examining the Perceived Value of Health Care Consumers According to the Gender Roles Eda Yilmaz Alarcin* and Mert Uydaci** The number of health institutions is increasing year by year in Turkey. In this case, it will be more important as the time goes by how the service offered is perceived by the health care consumers and how sensitively the consumers place an emphasis to perceived values dimensions. In this research, whether the value health care consumers perceive according to their sex and gender roles shows a difference for each perceived value dimension was aimed to be tested. The sample size was calculated as 384, based on a significance level of 0.05 and 416 questionnaire were collected. Questionnaire included sections about socio-demographic information, health care consumption behavior, gender roles inventory and consumer value dimensions. BEM Sex Role Inventory (BSRI) was used in measuring gender roles. The independent samples t test was used in order to test whether there was a significant difference in perceived value dimensions according to sex; the one-way analysis of variance was used in order to test whether there was a significant difference in perceived value dimensions according to gender roles. At the end of the study, it was seen that persons who have different sex do not seem to distinguish about their value perception for health care. Somehow, it was come to a conclusion that, the value that persons who have different gender roles perceive offers a difference for each value dimension. Respondents make decisions according to their gender roles rather than their sex. Keywords: Perceived Value, Gender Roles, Consumer Behavior 1. Introduction Intensity of competition between local firms and the international brands even in the globalized world, increase in consumer awereness, the excessive number of messages that consumers are exposed, variety of products and services, increasing the number of brand alternatives and experienced technological developments increase the importance of positive value perceptions for the brands. In Turkey where the contrubition of integrated marketing programs is recently understood for health services, creating positive value towards health institutions will become even more important over time. In this context, the construct of perceived value has recently gained much attention from marketers and researchers. Perceived value also plays important role in predicting purchase behavior and achieving sustainable competitive advantage. However, in recent years it has been recognized that consumer behavior is better understood when analyzed through perceived value. (Chen and Dubinsky 2003; Gallarza and Saura 2006). The view of individual's decision-making based on gender roles rather than biological sex has led us to research whether the importence given to perceived value dimensions is different according to the gender roles. Having masculine, feminine, androgynous or undifferentiated gender role of the individual may differ by the biological sex discrimination indicated as women and men. In this study, whether perceived value dimensions for health services are different according to the sex and gender roles is tested. *Asst.Prof.Dr. Eda Yilmaz Alarcin, Health Management Programme, Faculty of Health Sciences, Istanbul University, Turkey. Email: eyilmaz@istanbul.edu.tr Phone no: +90 212 4141500 Fax no: +90 212 4141515 **Prof.Dr. Mert Uydaci, Marketing Programme,Vocational School of Social Sciences, Marmara University, Turkey. Email: muydaci@marmara.edu.tr Phone no: +90 216 3089348 Fax no: +90 216 414571 1 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 2. Literature Review 2.1. Gender Roles Many researchers use the terms sex and gender interchangeably (Carver et al. 2013). Sex refers to whether one is born a male or a female. It is a biologically based distinction. Gender refers to personality traits, activities, interests, and behavior. Gender is a socially based distinction that we label with the terms masculine, feminine, and androgynous (Beere 1990). The other definition is “the beliefs people hold about members of the categories man or woman”. Many social psychological studies have shown that these gender roles vary among different cultures and ethnic groups (Özkan and Lajunen 2005). In the field of psychology, much research is conducted involving individuals‟ perceptions of gender roles, and behavioral as well as attitudinal correlates. Gender roles are cultural expectations about what is appropriate behavior for each sex (Weiten et al. 2012; Holt and Ellis 1998). Vafaei et al. (2014) submit that gender roles are often a self-perceived construct and are based on how individuals identify themselves as masculine or feminine. Gender role, sometimes referred to as an individual‟s psychological sex, has been defined as the fundamental, existential sense of one‟s maleness or femaleness. Since gender is culturally derived, gender role is similarly rooted in cultural understandings of what it means to be masculine or feminine. For many years, sex and gender were thought to be inseparable—that is, men were masculine and women were feminine. But what consumer behavior researchers, among others, recognized long ago was that some men were more feminine than masculine while some women were more masculine than feminine. In the postmodern culture in which we now live, this separation of gender from sex is even more apparent (Palan 2001). Gender-role identification is the extent to which a male is masculine and a female is feminine. Although different definitions of masculinity and femininity exist, masculine traits generally include being independent, ambitious, assertive, and dominant and feminine traits generally include being passive, being warm, lacking in leadership skills, and being dependent (Daigle and Mummert 2013). In 1974, Bem developed the Bem Sex-Role Inventory (BSRI), an instrument used to measure gender role perceptions. Bem (1979) emphasized the role of culture by defining the purpose of the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI) to assess the extent to which the culture‟s definitions of desirable female and male attributes are reflected in an individual‟s self-description. The BSRI is a measure of masculinityfemininity and gender roles. It assesses how people identify themselves psychologically. Bem's goal of the BSRI was to examine psychological androgyny and provide empirical evidence to show the advantage of a shared masculine and feminine personality versus a sex-typed categorization (Askin and Miman 2014). Both in psychology and in society at large, masculinity and femininity have long been conceptualized as bipolar ends of a single continuum; accordingly, a person has had to be either masculine or feminine, but not both. This sex-role dichotomy has served to obscure two very plausible hypotheses: first, that many individuals might be "androgynous"; that is, they might be both masculine and feminine, both assertive and yielding, both instrumental and expressive—depending on the situational appropriateness of these various behaviors; and conversely, that strongly sex-typed individuals might be seriously limited in the range of behaviors available to them as they move from situation to situation (Bem 1974). Bem (1974) was the first person who argued against the exclusive dichotomy of gender roles and defined four gender roles: A person with high masculine and low feminine identification would be categorized as „masculine‟, a person with high feminine identification and low masculine identification 2 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 would be categorized as „feminine‟, a person who had high identification with both characteristics would be categorized as „androgynous‟, and finally a person who has low identification with both dimensions would be considered „undifferentiated‟. She hypothesized that „androgynous‟ individuals regardless of their biological sex, depending on the situational appropriateness can be instrumental and assertive or expressive and yielding (Vafaei et al 2014). The BSRI is a widely used instrument in psychology and other fields because it measures masculine and feminine gender roles separately, is able to yield a measure of androgyny, and has adequate psychometric properties (Holt and Ellis 1998; Askin and Miman 2014). The adaptation of BSRI to Turkish society has been made by Kavuncu (1987). Kavuncu replaced the characteristics considered not to comply with Turkish society with the other characteristics suggested and reached a consensus, based on the evaluation of a group of professionals on the Turkish translation of inventory. The validty and reliabilty studies of Turkish form of BSRI have brought to a succesful conclusion. Kavuncu has also advised the short form of inventory (Dökmen 1999). BSRI includes both a Masculinity scale and a Femininity scale, each of which contains 20 personality characteristics. BSRI also includes a Social Desirability scale which contains 20 neutral characteristics. Social Desirability scale, which is completely neutral with respect to sex, serves primarily to provide a neutral context for the Masculinity and Femininity scales (Dökmen 1991). Social Desirability scale was not used in this study. 2.2. Concept of Perceived Value Perceived value has become a new strategic imperative for retailers; indeed, some authors have contended that perceived value has, in some respects, superseded more narrowly defined concepts such as quality and satisfaction (Sánchez-Fernández and Iniesta-Bonillo 2004). Perceived value has been found to be a powerful predictor of purchase intention (Chen and Dubinsky 2003). The importance of perceived value in relation to purchase intentions was documented in the early literature but it is only in recent years that the concept of perceived value has received increasing attention. It is suggested that perceived value can be enhanced by either adding benefits to the service or by reducing the outlays associated with the purchase and use of the service (Tam 2004). In fact, value is a key for gaining competitive advantage; it also has been seen as a definitive option to improve a destination‟s competitive edge. Although the concept of value is old and particular to consumer behavior, many authors have recognized a lack of interest in understanding and measuring perceived value (Gallarza and Saura 2006). While the first determinant of overall customer satisfaction is perceived quality, the second determinant of overall customer satisfaction is perceived value (Cronin et al. 2000). From the point of view of marketing strategy, creating perceived value in consumer marketing means meeting target customers‟ needs and increasing customer satisfaction. Perceived value has been used extensively by market-oriented firms to differentiate themselves from competitors (Chen and Dubinsky 2003). The concept of perceived value, that marketing researchers have recently been trying to grapple with and to study in greater depth, is stated as the essential result of marketing activities and is a first-order element in relationship marketing (Sánchez-Garcia et al. 2006; Mathwick et al. 2001; Ulaga and Chacour 2001). It has been emphasized by the authors that perceived value is a construct that has attracted the attention of a number of researchers. They also point out one aspect that has been assumed but little tested in the literature is that the valuation of a relationship is directly influenced by the successive transactions taking place over time. In this context, the perceived value of a purchase (transaction) is an antecedent of the quality of the relationship with an establishment (relationship). For this reason relationship quality aims to measure the lifetime value of a customer, which is an 3 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 aspect that the Marketing Science Institute (MSI) highlights among its research priorities for the coming years (Sánchez-Garcia et al. 2007). It has been seen in perceived value oriented-studies that there are different marketing terms representing “perceived value” are used and most of them have the same meaning. The terms that are frequently used in the literature are stated as; “perceived value” (Zeithaml 1988; Sweeney and Soutar 2001)”, “customer perceived value” (Grönroos 2010), “consumer value” (Holbrook 1999), “customer value” (Holbrook 1996; Woodruff 1997; Parasuraman 1997; Anderson et al. 1993; Slater and Narver 1994), “perceived customer value” (Chen and Dubinski 2003), “value” (De Ruyter et al. 1997), “perceived value for money” (Sweeney et al. 1999), “consumption value” (Tse et al. 1988; Sheth et al. 1991), “acquisition and transaction value” (Grewal et al. 1998; Parasuraman and Grewal 2000), “value consciousness” (Lichtenstein et al.1990) and“service value” (Bolton and Drew 1991). Numerous research studies have investigated this aspect in an articulate way but, to date, there has been no univocal definition of the perceived value. More precisely, although different conceptualizations exist in literature (client utility; benefits in relation to sacrifice; psychological price; monetary value and quality), a prevailing approach is recognizable which is the one based on the wellknown Anglo-Saxon concept of value for money, or rather, on the trade-off between monetary price and quality (Rigatti-Luchini and Mason 2010). Zeithaml (1988) reports considerable heterogeneity among consumers in the integration of the underlying dimensions of perceived value (Sinha and DeSarbo 1998). Zeithaml (1988, p. 14) found that, though consumers have different conceptions about perceived value, it can be captured in one overall definition: “Perceived value is the consumer‟s overall assessment of the utility of a product based on perceptions of what is received and what is given”. Essentially, value represents a trade-off of salient get and give-components, which are perceived as benefits and sacrifices, respectively (Chen and Dubinsky 2003; Gallarza and Saura 2006; Nasution and Ardin 2010). Although perceived value often has been defined as a trade-off of quality and price, several marketing researchers have noted that perceived value is a more obscure and complex construct, in which notions such as perceived price, quality, benefits, and sacrifice all are embedded and whose dimensionality requires more systematic investigation (Sinha and DeSarbo 1998; Kim 2002; Chen and Dubinsky 2003). On the one hand, perceived value is understood as a construct configured by two parts, one of benefits received by the customer (economic, social and relationship) and another of sacrifices made (price, time, effort, risk and convenience) (Sánchez-Garcia et al. 2007) According to Woodall (2003), perceived value is stated as any demand-side, personal perception of advantage arising out of a customer‟s association with an organization‟s offering, and can occur as reduction in sacrifice; presence of benefit (perceived as either attributes or outcomes); the resultant of any weighed combination of sacrifice and benefit (determined and expressed either rationally or intuitively); or an aggregation, over time, of any or all of these. Woodruff (1997) expands the concept of perceived value and describes it as a source of competitive advantage (Chen and Dubinsky 2003). According to Woodruff (1997), perceived value is “a customer's perceived preference for and evaluation of those product attributes, attribute performances, and consequences arising from use that facilitate (or block) achieving the customer's goals and purposes in use situations.” Parasuraman (1997) emphasize that perceived value occurs in consumers‟ mind regarding a product or service in consequence of assessment of benefits and costs that consumers perceived. 4 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 2.3. Perceived Value Dimensions According to different authors, recently an approach based on the conception of perceived value as a multidimensional construct has been gaining ground (Kim 2002; Eggert and Ulaga 2002; Yang and Peterson 2004; Huber and Morgan 2001; Snoj et al. 2004; Gallarza and Saura 2006). This approach allows us to overcome some of the problems of the traditional approach to perceived value, particularly its excessive concentration on economic utility (Sanchez-Garcia et al. 2007; Cengiz and Kirkbir 2007; Sanchez et al. 2006; Snoj et al. 2004). In general, the authors who study the concept of value as a multidimensional construct agree that two dimensions can be differentiated: one of a functional character and another of an emotional or affective type (Fandos-Roig et al. 2009). Considering all of these, single item scale does not address the concept of perceived value, since it is constructed with multiple dimensions. Therefore, measuring multiple components of perceived value has been recommended by many researchers (Lee et al. 2007). Zeithaml (1988) conceptualize perceived value with two dimensions as “benefit” and “sacrifice” which are seen in Table 1 (Zeithaml 1988; Cronin et al. 2000; Mcdougall and Levesques 2000; Tam 2004; Anderson et al. 1993; Lapierre 2000; Lichtenstein et al. 1990; Grönroos 2010). Table 1. Zeithaml‟s Perceived Value Dimensions Dimensions Description Benefit The benefit components of value include salient intrinsic attributes, extrinsic attributes, perceived quality, and other relevant high level abstractions. The sacrifice components of perceived value include monetary prices and nonmonetary prices such as time, energy and effort. Sacrifice Sweeney and Soutar (2001) has defined perceived value dimensions which are “emotional value”, “functional value- performance/ quality”, “functional value- price/ value for money” and “social valueenhancement of social self- concept”, as it is seen in Table 2. Table 2. Sweeney and Soutar‟s Perceived Value Dimensions Dimensions Description Emotional Value The utility derived from the feelings or affective states that a product generates Functional Value The utility derived from the perceived quality and (Performance/ Quality) expected performance of the product Functional Value The utility derived from the product due to the (Price/ Value for Money) reduction of its perceived short term and longer term costs Social Value The utility derived from the product‟s ability to (Enhancement of Social enhance social self-concept Self- Concept) Woodall (2003) presend perceived value dimensions as “exchange value”, “intrinsic value”, “use value” and “utilitarian value”. Stated perceived value dimensions are found in Table 3. 5 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Dimensions Exchange Value Intrinsic Value Use Value Utilitarian Value Table 3. Woodal‟s Perceived Value Dimensions Description Exchange value is object-based, and primarily influenced by the nature of the object and the market in which it is offered. The subject, however, has an influence on the process of ascribing value as he/she can either accept, reject and/ or negotiate the value that is offered. Intrinsic value is object-based, and is perceived as the object and subject interact (before, or during consumption). Use value is subject-based, and is also perceived as the object and subject interact (during, or after consumption). Utilitarian value is subject based, and can be identified at the point when intrinsic and/or use-value are compared with the sacrifice the subject is required to make in order to experience those forms of value. By means of a multi-dimensional procedure, Sanchez et al. (2004) have developed a scale of measurement of the perceived value of a purchase. On the basis of Sheth et al. (1991), and the PERVAL scale by Sweeney and Soutar (2001) Sánchez-Garcia et al. (2007) have developed the GLOVAL scale which measures the perceived value of a purchase, including not only the establishment but also the product purchased there, widening the scope of the PERVAL scale (Cengiz and Kırkbir 2007; Sánchez-Garcia et al. 2007). Sánchez-Garcia et al. (2006) conducted the survey on tourists who buy tourism packages. The dimensions of scale which is discussed in this research can be seen below: Table 4. Sánchez et al.‟s Perceived Value Dimensions Description Functional value of the It can be stated as a customer‟s perception regarding travel agency: installations installations‟ location, structure and so on. Dimensions Functional value of the contact personnel of the travel agency: professionalism Functional value of the tourism package (quality) Functional value price It can be stated as a customer‟s perception regarding contact person‟s advices, knowledge about the job and products/ services, professionalism etc. It can be stated as a customer‟s perception regarding product/ service quality, performance and how it is served. It can be stated as a customer‟s perception regarding the price of served service/ product or whether the price is the main criterion etc. Emotional value of the It can be stated as a customer‟s perception regarding purchase how a customer feels in the service point, motivation of contact person etc. Social value of the It can be stated as a customer‟s perception regarding purchase social approval and gaining reputation etc. 6 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 The other perceived value dimensions in the literature can be seen in Table 5. Author (s) Table 5. Other Perceived Value Dimensions in the Literature Dimensions Holbrook (1999; 1996) Sheth et al. (1991) Al-Sabbahy et (2004) Sin et al. (2001) Extrinsic Value (Efficiency, Excellence, Status, Esteem) Intrinsic Value (Play, Aesthetics, Ethics, Spirituality) Functional Value, Social Value, Emotional Value, Epistemic Value, Conditional Value al. Acquisition Value, Transaction Value Aesthetic Value, Instrumental Value, Social Value Patriotic Value Jensen and Hansen Harmony, Excellence, Emotional Stimulation, (2007) Acknowledgement, Circumstance Value De Ruyter et al. Emotional Value, Practical Value, Logical Value (1997) Grewal et al. (1998) Perceived Acquisition Value, Perceived Transaction Value Kantamneni and Core Value, Personal Value, Sensory Value, Commercial Coulson (1996) Value Parasuraman and Acquisition Value, Transaction Value, In-use Value, Grewal (2000) Redemption Value Tse et al. (1988) Aesthetics, Instrumental: Basic Needs, Social: Acceptance and Instrumental: Higher Level Needs, Social: Morality, Simple, Fit My Status, Social: Trendiness, Value Babin et al. (1994) Hedonic Value, Utilitarian Value Butz and Goodstein Expected Value, Desired Value, Unanticipated Value (1996) 3. The Methodology and Model The purpose of this research is to investigate if the value that health care consumers perceive about health care is making a difference, firstly according to sex and secondly according to gender role. The first purpose has been tested by “independent samples t test” and the second purpose has been tested by “one-way analysis of variance”. The population of the research is the health care consumers living in Istanbul. As all those who live in Istanbul can be health care consumers, sampling size has been determined over Istanbul. According to TUIK data (www.tuik.gov.tr), the population of Istanbul is 14,377,018.- as of 2014. Confidence interval is 95 %, sampling error is ± 5 % has been calculated as (d=0.05) and n=384. Young persons have been aimed mostly in the research. It is because, when older persons apply to health institutions, they are accompanied by a young relative. Besides, it has been seen that older and low-educated persons are unwilling to respond the questionnaire during the research. Questionnaire has been used as data collection method in the research. While making the questionnaire form, “BEM Sex Role Inventory” has been referred to in determining the gender roles 7 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 and Sanchez et al. (2006)‟s Gloval Scale has been referred to in determining perceived value items. The questionnaire form has been put into practice with health service customers selected as simple sampling between 18th and 30th December 2014 in Taksim, Bakırköy and Kadıköy by face-to-face interview. 416 appraisable questionnaire forms have been gained. According to the result of extreme value analysis, 24 of the forms have been omitted from the analysis and 392 ones have been evaluated. For the evaluation of understandability and reliability of the questions in the questionnaire form, the pilot questionnaire has been put into practice with 50 persons appropriate to sample mass and necessary corrections have been made according to the received results. It has been tried to be tested if the value that the questionnaire respondents perceive about the health care according to their sex and gender roles is distinguishing or not. As seen in Figure 1, the model research includes variable groups as „perceived value‟, „sex‟ and „gender roles (BEM Sex Role Inventory)‟. In order to test the purposes of the research, the established hypotheses have been listed as follows: H1a = Functional value perceptions about the health care of the health care consumers who have responded to the research do not make a significant difference according to sex. H1b = Social value perceptions about the health care of the health care consumers who have responded to the research do not make a significant difference according to sex. H1c = Emotional value perceptions about the health care of the health care consumers who have responded to the research do not make a significant difference according to gender. H1d = Functional value of the personnel (professionalism) perceptions about the health care of the health care consumers who have responded to the research do not make a significant difference according to sex. H2a = Functional value perceptions about the health care of the health care consumers who have responded to the research do not make a significant difference according to gender role. H2b = Social value perceptions about the health care of the health care consumers who have responded to the research do not make a significant difference according to gender role. H2c = Emotional value perceptions about the health care of the health care consumers who have responded to the research do not make a significant difference according to gender role. H2d = Functional value of the personnel (professionalism) perceptions about the health care of the health care consumers who have responded to the research do not make a significant difference according to gender role. 8 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Figure 1. Research Model Perceived Value 4. The Functional Value Gender Social Value Emotional Value Gender Roles Functional Value of Personnel (Professionalism) Perceived Value Findings Demographic Characteristics of the Research Respondents Frequency and percentage distributions about the socio-demographic characteristics of the research respondents have been given in Table 6. According to this, 43.1 % of the research respondents are between 21 and 30 years old; 66.3 % are women; 77.8 % are single; 75.2 % are university educated; 62 % are students and 33.2 % have an income between 2,001.- and 3,000.- TL. As one of the limitations of the research, older and low-educated persons were unwilling to respond the questionnaire during the application of the questionnaire forms, so those who have responded have become younger and educated. Table 6. Demographic Characteristics Description Age ≤ 20 21 to 30 31 to 40 41 to 50 51 to 60 ≥ 61 Sex Female Male Frequency Percent 142 169 43 26 9 3 36.2 43.1 11.0 6.6 2.3 0.8 260 132 66.3 33.7 Description Frequency Percent Education Grade School High School University Postgraduate 18 53 295 26 4.6 13.5 75.2 6.7 Marital Status Single Married 305 87 77.8 22.2 9 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Monthly Net Income of the Family ≤ 1000 TL 10012000 TL 2001- 3000 TL 3001- 4000 TL 4001- 5000 TL 5001- 6000 TL 6001- 7000 TL ≥ 7001 TL 35 127 130 63 18 10 2 7 8.9 32.4 33.2 16.1 4.6 2.6 0.5 1.8 Occupation Unemployed Self Employed Housewife Student Worker Official Contract Employee Retired 49 22 18 243 19 16 15 10 12.5 5.6 4.6 62.0 4.8 4.1 3.8 2.6 Health Care Consumption Preferences of the Research Respondents When health care consumption preferences of the research respondents are investigated, it is seen that majority of the respondents (61.7 %) have preferred to receive health care from Public Hospitals. The ratio of those who have not preferred university hospitals (76 %) is more that those who have preferred (24 %). The ratio of those who have preferred District Polyclinic, Community Health Center, Physician‟s Private Office, Medical Center and Private Hospitals has become lower than those who have not preferred. In this case, it can be said that the respondents have preferred to receive health care mostly from Public Hospitals and the ratio of preference for the other health institutions is low. When the research respondents‟ social security has been evaluated, it has been seen that majority is under 4A cover with a ratio of 60.5 %. These results have been shown in Table 7. Table 7. Health Care Consumption Preferences Description Frequency Percent Public Hospital Yes 242 61.7 University Hospital No 298 76.0 District Polyclinic No 370 94.4 Community Health Center No 319 81.4 Physician‟s Private Office No 379 96.7 Medical Center No 372 94.9 Private Hospital No 275 70.2 Social Security 4A 237 60.5 4B 62 15.8 4C 48 12.2 Private Health Insurance 17 4.3 Green Card 8 2.0 None 20 5.1 Distributions about the Gender Roles BEM Sex Role Inventory has been referred to in order to determine the gender roles of the research respondents. Respondents have replied how the statements which took place in femininity and masculinity scales described themselves between „1- I do not agree at all‟ and „7- I exactly agree‟. As seen in Table 8, the ratio of masculine gender role of the respondents is 20.2 %; the ratio of feminine gender role is 15.8 %; the ratio of androgen gender role is 16.1 % and the ratio of undifferentiated gender role is 48%. When the research respondents‟ sex distributions are investigated, the majority is woman but as for the distributions about gender roles, it is seen that the lowest group is feminine. 10 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Table 8. Distributions about the Gender Roles Gender Roles Frequency Percent Masculine 79 20.2 Feminine 62 15.8 Androgynous 63 16.1 Undifferentiated 188 48.0 When the distribution of the sex of the respondents is investigated according to the gender roles, only 22.3% of women are feminine but 12.7 % of them are masculine; 16.5% of them are androgen and 48.5 % of them seem to have undifferentiated gender. 35 % of men are masculine; 3 % are feminine; 15 % are androgen and 47 % of them seem to have undifferentiated gender. These results have been shown in Table 9. Table 9. Distributions of Female and Male According To Gender Roles Masculine Feminine Androgynous Undifferentiated Frequency % Frequency % Frequency % Frequency % Female 33 12.7 58 22.3 43 16.5 126 48.5 Male 46 35 4 3 20 15 62 47 Reliability Analysis Cronbach Alpha coefficient has been referred to for the measurement of the BSRI which took place in the questionnaire and the measurement of the reliability of perceived value scale. Feminine scale and masculine scale under BSRI have been analysed separately. The 0.793 value of the analysis result applied to 20 variables which took place in feminine scale and the 0.826 value of the analysis result applied to 20 variables which took place in masculine scale have been considered to be reliable. Analysis applied to 24 variables for the reliability of the perceived value scale has shown that the scale is reliable. Somehow, when a variable which has risen alpha coefficient has been omitted from the scale, the analysis has been repeated and the 0.884 value has shown that the scale is reliable. Factor Analysis Factor analysis has been applied to the perceived value scale in the research. „Varimax Rotation‟ has been used to make factor structure simple and to make its comment easy. For the factor analysis applied to the perceived value scale, the variables under the factor load 0.500 have been omitted from the analysis and it has been repeated. According to Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) sampling adequacy result gained as a result of factor analysis applied to 18 variables scale, sampling size has been found sufficient (0.883). The analysis has been continued with Bartlett test significance value 0.000. At the end of the analysis, four factor groups have been gained. These factors explain 67.212 % of the total variance. 11 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Table 10. Factor Analysis Results Belonging To The Perceived Value Scale Items Factor Loadings F1 It is important for me that health institution to be spacious, modern and clean. It is important for me that health institution to be neat and well organized. It is important for me that service which I purchased from health institution to be well organized. It is important for me that personnel working in health institution to know their job well. It is important for me that the quality of the service which I purchased from health institution to be maintained throughout. It is important for me that purchasing health service to improve the way others perceive me. It is important for me that using health institutions‟ (brands) services to has improved the way others perceive me. It is important for me that people who take service which I purchased to obtain social approval. It is important for me that health institutions‟ (brands) services to be used by many people that I know. It is important for me to be comfortable with the service I purchased. It is important for me that the personnel not to pressure me to decide quickly. It is important for me that the personnel to give me a positive feeling. It is important for me that the personnel to be always willing to satisfy my wishes as a customer, whatever product/ service I wanted to buy. It is important for me to feel relaxed in the health institution. It is important for me that personnel working in health institution to be a good professional and to be up-to-date about new items and trends. It is important for me that personnel working in health institution to know the services which the institution offers. It is important for me that the result of the service which I purchased from health institute to be as expected. It is important for me that the advices of personnel working in health institution to be valuable. Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings (% of Variance) Cronbach's Alpha F2 F3 F4 .872 .761 .749 .746 .652 .924 .910 .836 .812 .727 .659 .656 .621 .595 .759 .639 .607 .586 20.563 17.785 14.648 14.215 .892 .906 .783 .740 12 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 First factor group is „functional value‟; second factor group is „social value‟; third factor group is „emotional value‟; and fourth factor group is „functional value of personnel (professionalism)‟. The results of factor analysis belonging to the perceived value scale have been shown in Table 10. The factor groups gained in this study have been evaluated with the dimensions which took place in Sanches et al.‟s (2006) study. While six dimensions have been mentioned in their study, four dimensions have been gained about the perceived value for health care consumers in our study. Besides, when distributions of the items under the dimensions have been investigated, similarities and differences have been met. While the items under „social value‟ and „emotional value‟ dimensions have been distributed as similar as Sanchez et al.‟s, the items under „functional value‟ and „functional value of personnel (professionalism)‟ dimensions have shown differences from the reference study. It has been seen that, especially under the „functional value‟ in the reference study, the item :„it is important for me that personnel working in health institution to know their job well‟ is under „functional value of personnel (professionalism)‟; the item under „quality‟ dimension: “it is important for me that service which I purchased from health institution to be well organized‟ and „it is important for me that the quality of the service which I purchased from health institution to be maintained throughout‟ have been distributed. While the item: „it is important for me that the result of the service which I purchased from health institute to be as expected‟ has taken place under „quality‟ dimension in the reference study but under „functional value of personnel (professionalism)‟ in our study. „Quality‟ and „price‟ dimensions which were listed among the perceived value dimensions by Sanchez et al.‟s could not be gained in this study about health care consumers. Difference Tests It has been tested by independent samples t test if it is different according to the sex for each dimension of the value that research contributor health care consumers perceive. Test results have been shown in Table 11. Functional value perception does not show a significant difference according to the sex. The distribution is homogeneous for “sig=0.430 >0.05” value when Levene test results are investigated. H1a hypothesis has been accepted since p value 0.417 is bigger than 0.05. Social value perception does not show a significant difference according to the sex. The variances of both group are equal for “sig=0.900 > 0.05” value according to the Levene test results. H1b has been accepted since p value is 0.305 > 0.05. Emotional value perception does not show a significant difference according to the sex. The distribution is homogeneous for “sig=0.478>0.05” value according to Levene test results. H1c has been accepted since p value is 0.194 > 0.05. Functional value of personnel (professionalism) perception does not show a significant difference according to the sex. The distribution is homogeneous for “sig=0.065>0.05” value according to Levene test results. H1d has been accepted since p value is 0.455 > 0.05. It has been seen that perceived value dimensions do not show a significant difference according to the sex. 13 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Table 11. Independent Samples T Test Results of Perceived Value Dimensions According To Sex Description N Mean Std.Dev. df T p Hypothesis Functional Value 390 .812 .417 H1a accepted Female 260 6.79 0.57 Male 132 6.74 0.53 Social Value 390 -1.026 .305 H1b accepted Female 260 5.04 1.77 Male 132 5.23 1.74 Emotional value 390 1.302 .194 H1c accepted Female 260 6.50 .76 Male 132 6.40 .74 Functional Value of 390 .748 .455 H1d accepted Personnel (Professionalism) 260 6.54 .62 Female 132 6.49 .76 Male Whether the value for each dimension the research respondents perceive about health care shows a difference according to gender roles has been tested by one way analysis of variance. Firstly, group variances are not equal because p value 0.000 is lower than 0.05 gained at the end of Levene test as a result of analysis functional value dimension. Therefore, Welch and Brown-Forsythe tests have been applied. P value 0.000 and 0.05 has been gained smaller at the end these two tests. According to this result, it can be said that functional value perceptions about health care of respondents who have different gender roles show differences. Tamhane Post Hoc Test has been used to identify which gender roles have caused this difference. According to the test result, undifferentiated ones constitute gender role which have the lowest functional value perceptions. H2a hypothesis has been rejected. Analysis results have been shown in Table 12. Table 12. One-Way Analysis of Variance Results of Functional Value Perception According To Gender Roles Statistic df1 df2 Sig. 16.042 3 388 .000 Levene 7.110 3 185.243 .000 Welch 16.382 3 318.238 .000 Brown- Forsythe (I) gender role (J) gender role Mean Difference (I-J) Std.Error Sig. Masculine Feminine -.01531 .03637 .999 N: 79 androgynous -.00410 .03661 1.000 Mean: 6,8911 undifferentiated .25603(*) .05902 .000 feminine masculine .01531 .03637 .999 N: 62 androgynous .01121 .04069 1.000 Mean: 6,9065 undifferentiated .27135(*) .06164 .000 androgynous masculine .00410 .03661 1.000 N: 63 feminine -.01121 .04069 1.000 Mean: 6,8952 undifferentiated .26013(*) .06178 .000 undifferentiated masculine -.25603(*) .05902 .000 N: 188 feminine -.27135(*) .06164 .000 Mean: 6,6351 androgynous -.26013(*) .06178 .000 14 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 For p value 0.000 gained as a result of Levene test for the analysis made to show whether social value perceptions about health care of the research respondents distinguish according to gender roles, Welch and Brown-Forsythe tests have been applied. P 0.000 value has been gained at the end of the tests. According to this result, it can be said that respondents‟ social value perceptions about health care show differences according to different gender roles. H2b has been rejected. According to the results of Tamhane Post Hoc Test, androgynous and feminines have higher social value perceptions than masculines and undifferentiated ones. The results of the analysis have been shown in Table 13. Table 13. One-Way Analysis of Variance Results of Social Value Perception According To Gender Roles Statistic df1 df2 Sig. 6.537 3 388 .000 Levene 10.959 3 160.256 .000 Welch 9.227 3 277.818 .000 Brown- Forsythe (I) gender role (J) gender role Mean Difference (I-J) Std.Error Sig. Masculine feminine -.98224(*) .27041 .002 N: 79 androgynous -.83836(*) .30120 .036 Mean: 4,8323 undifferentiated .03973 .25351 1.000 feminine masculine .98224(*) .27041 .002 N: 62 androgynous .14388 .26057 .995 Mean: 5,8145 undifferentiated 1.02196(*) .20358 .000 androgynous masculine .83836(*) .30120 .036 N: 63 feminine -.14388 .26057 .995 Mean: 5,6706 undifferentiated .87808(*) .24299 .003 undifferentiated masculine -.03973 .25351 1.000 N: 188 feminine -1.02196(*) .20358 .000 Mean: 4.7926 androgynous -.87808(*) .24299 .003 Whether the emotional value perceptions of the research respondents about health care shows a difference according to gender roles has been tested by one way analysis of variance. P value is 0.000 gained as the result of Levene test. P value 0.000 has been gained in Welch and BrownForsythe tests applied because of the first test. So, H2c hypothesis has been rejected. Emotional value perceptions show a significant difference according to the respondents‟ different gender roles. According to Tamhane Post Hoc test results, feminines respect value more than undifferentiated ones; androgenes respect value more than undifferentiated ones and masculines for emotional value perception. The result of the analysis has been shown in Table 14. 15 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Table 14. One-Way Analysis of Variance Results of Emotional Value Perception According To Gender Roles Statistic df1 df2 Sig. 17.342 3 388 .000 Levene 15.043 3 184.039 .000 Welch 17.098 3 333.883 .000 Brown- Forsythe (I) gender role (J) gender role Mean Difference (I-J) Std.Error Sig. Masculine feminine -.19114 .08923 .188 N: 79 androgynous -.26574(*) .08997 .022 Mean: 6.5089 undifferentiated .24929 .10114 .084 feminine masculine .19114 .08923 .188 N: 62 androgynous -.07460 .06597 .836 Mean: 6.7000 undifferentiated .44043(*) .08054 .000 androgynous masculine .26574(*) .08997 .022 N: 63 feminine .07460 .06597 .836 Mean: 6.7746 undifferentiated .51503(*) .08136 .000 undifferentiated masculine -.24929 .10114 .084 N: 188 feminine -.44043(*) .08054 .000 Mean: 6.2596 androgynous -.51503(*) .08136 .000 Whether the functional value of personnel (professionalism) perceptions of the research respondents about health care shows a difference according to gender roles has been tested. P value 0.000 has been gained as a result of Levene test. Group variances are not homogeneous for this variable. Because of this result, Welch and Brown-Forsythe tests have been applied and p value 0.000 has been gained. Since the p value gained is smaller than 0.05, H2d hypothesis has been rejected. It can be said that professionalism value perceptions of the respondents who have different gender roles show differences. According to Tamhane Post Hoc test, undifferentiated ones respect value for professionalism value perceptions less than respondents with the other gender roles. The result of the analysis has been shown in Table 15. Table 15. One-Way Analysis of Variance Results of Functional Value of Personnel (Professionalism) Perception According To Gender Roles Statistic df1 df2 Sig. 3 388 .000 Levene 10.784 3 175.084 .000 Welch 10.649 3 337.494 .000 Brown- Forsythe 11.882 (I) gender role (J) gender role Mean Difference (I-J) Std.Error Sig. Masculine feminine -.04333 .09179 .998 N: 79 androgynous -.16782 .08786 .302 Mean: 6.6139 undifferentiated .25754(*) .09048 .029 feminine masculine .04333 .09179 .998 N: 62 androgynous -.12449 .07779 .510 Mean: 6.6573 undifferentiated .30088(*) .08074 .002 androgynous masculine .16782 .08786 .302 N: 63 feminine .12449 .07779 .510 Mean: 6.7817 undifferentiated .42536(*) .07623 .000 undifferentiated masculine -.25754(*) .09048 .029 N: 188 feminine -.30088(*) .08074 .002 Mean: 6.3564 androgynous -.42536(*) .07623 .000 16 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 5. Summary and Conclusions In this research, whether the value health care consumers perceive according to their sex and gender roles shows a difference for each perceived value dimension has been aimed to be tested. The findings gained are that when the value perceptions which do not show differences are analyzed according to the sex factors, it is seen that they show a difference according to the gender roles. It can be submitted that this is an important finding for the marketing studies to be conducted in future. When thought that the researches made in marketing field on health care consumers especially in Turkey are limited, this research can be considered to be a leading study for further ones. Sex element seems to be insufficient in explaining the emphasis placed on the perceived value dimensions according to the research findings. Respondents make a decision according to their gender roles rather than their sex. So, it will be useful to determine which gender role the target market have while trying especially to create a positive value perception and establishing marketing programmes for health care consumers. When the respondents‟ frequency distributions grounded on sex, it is seen that the majority is women. Upon determination of the gender roles, it is seen that the majority of the respondents have undifferentiated gender role and feminines have a percentage of only 15.8 within all the respondents. The percentage of those who has feminine gender role within women is at the level of 22.3 percent. These results show that discrimination upon gender roles rather than man and woman can be more useful for social researches. When the health care and health institutions are discussed, it can be said that masculines are focused on the functional value perception such as orderliness, cleanliness, providing good service and on the characteristics to create a professionalism value perception such as personnels‟ knowledge level, their following new developments and being good professionals. In addition to these characteristics, feminines and androgynous place emphasis for the elements to create an emotional value perception such as feeling comfortable in health institutions, feeling good about the personnels and a social value perception such as, finding acceptance and reputation. Undifferentiated ones constitute those who have low value perception for all dimensions. The statement „I am a virtuous one‟ taking place in sex role inventory has been reacted by some respondents. This situation can be concerned with the perception that the concept „virtue‟ is connected with sexualism in Turkey. That the statement „I am a virtuous one‟ takes place in feminine scale can be evaluated as a supportive indicator for this connection. The findings gained about the perceived value dimensions show differences from the reference article. According to this, while the perceived value dimensions are being constituted by „functional value‟, „functional value of personnel (professionalism)‟, „quality‟, „price‟, „emotional value‟ and „social value‟ in the reference article of Sanchez et al.‟s (2006); four dimensions have been gained in this research applied to health care consumers in Turkey: „functional value‟, „social value‟, „ emotional value‟ and „functional value of personnel (professionalism)‟. Besides, the items constituting the said dimensions have allocated differently in this study. Therefore, some other studies can be done to test the validity of the perceived value dimensions for health care consumers and Turkey. References Al-Sabbahy, H, Ekinci, Y and Riley, M 2004, “An investigation of perceived value dimensions: Implications for hospitality research”, Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 42, No. 2, pp.226-234. Anderson, JC, Dipak, JC and Chintagunta, PK 1993, “Customer value assessment in business markets: A state-of- practice study”, Journal of Business to Business Marketing, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp.3-30. 17 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Askin, N and Miman, M 2014, “Bem sex inventory - means and SD of the BSRI items among Turkish male and female university students in Mersin”, Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 113, pp.234-237. Babin, BJ, Darden, WR and Griffin M 1994, “Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp.644-656. Beere, CA 1990, Gender Roles: A Handbook of Tests, and Measures, Westport, USA, Greenwood Press. Bem, SL 1974, “The measuremenet of psyhological androgyny”, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 42, No. 2, pp.155-162. Bolton, RN and Drew JH 1991, “A multistage model of customers‟ assessments of service quality and value”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 17, pp.375-384. Butz, HE and Goodstein, LD 1996, “Measuring customer value: Gaining the strategic advantage”, Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 24, No. 3, pp.63-77. Carver, LF, Vafaei, A, Guerra, R, Freire A and Phillips SP 2013, “Gender differences: Examination of the 12-item Bem sex role inventory (BSRI-12) in an older Brazilian population”, Plos One, Vol. 8, No. 10, pp.1-7. Cengiz, E and Kirkbir F 2007, “Customer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale in hospitals”, Problems and Perspectives in Management, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp.252-268. Chen, Z and Dubinsky AJ 2003, “A conceptual model of perceived customer value in e-commerce: A preliminary investigation”, Psychology and Marketing, Vol. 20, No. 4, pp.323-346. Cronin, JJ, Brady MK and Hult G 2000, “Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 76, No. 2, pp.193-218. Daigle, LE and Mummert SJ 2013, “Sex-Role identification and violent victimization: Gender differences in the role of masculinity”, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Vol. 29, No. 2, pp.255278. De Ruyter, K, Wetzels, M, Lemmink, J and Mattsson, J 1997, “The dynamics of the service delivery process: A value-based approach”, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 14, pp.231-243. Dökmen, Z 1991, “Bem cinsiyet rolü envanteri'nin geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması- A validity and reliability research about BSRI”, Dil ve Tarih-Coğrafya Fakültesi Dergisi- Journal of Languages and History-Geography, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp.81-89. Dökmen, ZY 1999, “BEM cinsiyet rolü envanteri kadınsılık ve erkeksilik ölçekleri Türkçe formunun psikometrik özellikleri- BSRI feminity and masculinity scales‟ psychometric properties for Turkish form”, Kriz Dergisi- Journal of Crisis, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp.27-40. Eggert, A and Ulaga, W 2002, “Customer perceived value: A substitute for satisfaction in business markets”, The Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, Vol. 17, No. 2/3, pp.107-118. Fandos-Roig, JC, Sánchez-García, J and Moliner-Tena, MA 2009, “Perceived value and customer loyalty in financial services”, The Service Industries Journal, Vol. 29, No. 6, pp.775-789. Gallarza, MG and Saura, IG 2006, “Value dimensions, perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty: An investigation of university students travel behavior”, Tourism Management, Vol. 27, pp.437-452. Grewal, D, Monroe, KB and Krishnan, R 1998, “The effects of price comparison advertising on buyers‟ perceptions of acquisition value, transaction value, and behavioural intentions”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 62, No. 2, pp.46-59. Grönroos, C 2010, “Value-driven relational marketing: From products to resources and competencies”, Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 13, No. 5, pp.407-419. Holbrook, MB 1996, “Customer value - A framework for analysis and research”, Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp.138-142. Holbrook, MB 1999, Consumer Value: A Framework for Analysis and Research, London, Routledge. 18 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Holt, C and Ellis, J 1998, “Assessing the current validity of the Bem sex role inventory”, Sex roles: A Journal of Research, Vol. 39, pp.929-941. Huber, F, Herrmann, A and Morgan, RE 2001, “Gaining competitive advantage through customer value oriented management”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp.41-53. Jensen, O and Hansen, KV 2007, “Consumer values among restaurant customers”, Hospitality Management, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp.1-20. Kantamneni, SP and Coulson, KR 1996, “Measuring perceived value: Findings from preliminary research”, The Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp.72-86. Kim, YK 2002, “Consumer value: An application to mall and internet shopping”, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, Vol. 30, No. 12, pp.595-602. Lapierre, J 2000, “Customer-perceived value in industrial contexts”, Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, Vol. 15, No. 2/3, pp.122-145. Lee, CK, Yoon, YS and Lee, SK 2007, “Investigating the relationships among perceived value, satisfaction, and recommendations: The case of the Korean DMZ”, Tourism Management, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp.204-214. Lichtenstein, DR, Netemeyer, RG and Burton, S 1990, “Distinguishing coupon proneness from value consciousness: An acquisition transaction utility theory perspective”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 54, pp.54-67. Mathwick, C, Malhotra, N and Rigdon, E 2001, “Experiential value: Conceptualization, measurement and application in the catalog and internet shopping environment”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 77, No. 1, pp.39-56. McDougall, GHG and Levesque, T 2000, “Customer satisfaction with services: Putting perceived value into the equation”, Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 14, No. 5, pp.392-410. Nasution, RA and Ardin, I 2010, “Consumer perceived value analysis of new and incumbent brands of Gudang Garam and Sampoerna”, The Asian Journal of Technology Management, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp.16-30. Özkan, T and Lajunen, T 2005, “Masculinity, femininity, and the Bem sex role inventory in Turkey”, Sex Roles, Vol. 52, No. 1/2, pp.103-110. Palan, KM 2001, “Gender identity in consumer behavior research: A literature review and research agenda”, Academy of Marketing Science Review, Vol. 10, pp.1-24. Parasuraman, A 1997, “Reflections on gaining competitive advantage through customer value”, Journal of The Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp.154-161. Parasuraman, A and Grewal, D 2000, “The impact of technology on quality-value-loyalty chain: A research agenda”, Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp.168-174. Rigatti-Luchini, S and Mason, MC 2010, “An empirical assessment of the effects of quality, value and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in food events”, International Journal of Event Management Research, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp.46-61. Sánchez-Fernández, R and Iniesta-Bonillo, MÁ 2004, “Efficiency and quality as economic dimensions of perceived value: Conceptualization, measurement, and effect on satisfaction”, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol. 16, pp.425-433. Sánchez-Garcia, J, Callarisa, L, Rodriguez, RM and Moliner, MA 2006, “Perceived value of the purchase of a tourism product”, Tourism Management, Vol. 27, pp.394-409. Sánchez-Garcia, J, Moliner-Tena, MA, Callarisa-Fiol, LJ and Rodríguez-Artola, RM 2007, “Relationship quality of an establishment and perceived value of a purchase”, The Service Industries Journal, Vol. 27, No. 2, pp.151-174. Sheth, JN, Newman, BI and Gross, BL 1991, “Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 22, pp. 159-170. Sin, L YM, So, S LM, Yau, O HM and Kwong, K 2001, “Chinese women at the crossroads: An ampirical study on their role orientations and consumption values in Chinese society”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp.348-367. 19 Proceedings of 7th Annual American Business Research Conference 23 - 24 July 2015, Sheraton LaGuardia East Hotel, New York, USA, ISBN: 978-1-922069-79-5 Sinha, I and DeSarbo, WS 1998, “An integrated approach toward the spatial modeling of perceived customer value”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 35, pp.236-249. Slater, SF and Narver, JC 1994, “Market orientation, customer value, and superior performance”, Business Horizons, pp.22-28. Snoj, B, Korda, AP and Mumel, D 2004, “The relationships among perceived quality, perceived risk and perceived product value”, Journal of Product & Brand Management, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp.156167. Sweeney, JC, and Soutar, GN 2001, “Consumer perceived value: the development of multiple item scale”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 77, No. 2, pp.203-220. Sweeney, JC, Soutar, GN and Johnson, LW 1999, “The role of perceived risk in the quality-value relationship: A study in a retail environment”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 75, No. 1, pp.77- 105. Tam, JLM 2004, “Consumer satisfaction, service quality and perceived value: An integrative model”, Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 20, pp.897-917. Tse, DK, Wong, JK and Tan, CT 1988, “Towards some standardized cross-cultural consumption values”, Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 15, pp.387-395. Ulaga, W and Chacour, S 2001, “A prerequisite for marketing strategy development and implementation”, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 30, pp.525-540. Vafaei, A, Alvarado, B, Tomás, C, Muro, C, Martinez, B and Zunzunegui, ZM 2014, “The validity of the 12-item Bem sex role inventory in older Spanish population: An examination of the androgyny model”, Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, Vol. 59, pp.257-263. Weiten, W, Dunn, D and Hammer, E 2012, Psychology Applied to Modern Life: Adjustment in the 21st Century.Belmont, CA, Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. Woodall, T 2003, “Conceptualising value for the customer: An attributional, structural and dispositional analysis”, Academy of Marketing Science Review, Vol. 12, pp.1-42. Woodruff, RB 1997, “Customer value: The next source for competitive advantage”, Journal of The Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp.139-153. www.tuik.gov.tr, accessed December 15.2014. Yang, Z and Peterson, RT 2004, “Customer perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty: The role of switching costs”, Psychology and Marketing, Vol. 21, No. 10, pp.799-822. Zeithaml, VA 1988, “Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 52, pp.2-22. 20