MJHS MALTA JOURNAL OF HEALTH SCIENCES ISSN 2312-5705

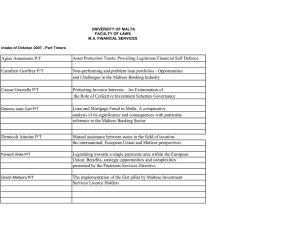

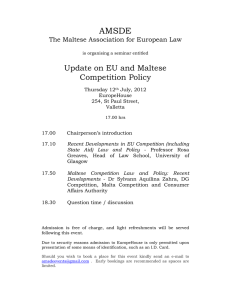

advertisement