Proceedings of European Business Research Conference

advertisement

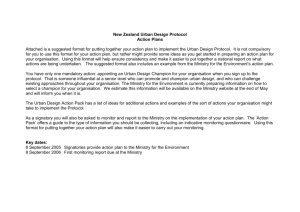

Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 Performance Management in the Brunei Public Sector Thuraya Farhana Haji Said When new public management (NPM) reform was introduced in advanced countries in 1990s, many developing countries have opted the same reform to modernise and improve public-sector performance. Thus, the emergence of NPM has highlighted the importance of performance management (PM) in the public sectors, which includes institution of strategic planning together with key performance indicators to measure performance objectives achieved or otherwise. However, there is a number of literature surrounding the NPM debate concerning the fact that although NPM ideas are influential, they are more so at the level of rhetoric than practice. This study extends the NPM and PM literature in the developing countries by addressing the major question: to what extent is PM institutionalised in the Brunei public sector. Recently, government ministries and departments have developed their strategic plans by setting their priority targets towards achieving ‘Wawasan’ (Vision) Brunei 2035. Concepts from institutional theory are theoretically relevant to explain the nature of change in which the implementation of PM would mean in Brunei Public sector. A qualitative case study has been used to portray the analysis of degree of institutionalisation whereby data were collected through semi-structured interviews, document reviews, informal conversation and observations. Despite the attempt to promote PM policy, the data collected show that PM has become loosely coupled to other organisational activities. Key words: New Public Management, Path Dependence, Decoupling 1.0 Introduction The influence of the new public management (NPM) movement in Brunei administrative reform has been noticeable in recent decades (Haji Saim, 2005; Athmay, 2008). Many governments have aimed to introduce new managerial rationality in public sector, believing that public sector management is inefficient and can only be challenged by the introduction of new public management derived from private sector management ideas and thinking (Hood, 1991; Dunleavy and Hood, 1994; Osborne and Gaebler, 1992; Ferlie et al., 1996; Pollitt, 2009). The influence of the NPM has also led to the introduction of performance management which promises better government, empowerment and better mechanisms of public accountability (Athmay, 2008). As a result, the Brunei government appears to believe that application of NPM as its preferred solution for productivity improvement in the public sector, in particular, through Thuraya Farhana Haji Said, School of Management, University of Surrey, United Kingdom. Email: t.hajisaid@surrey.ac.uk 1 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 the practice of performance management (PM). In Brunei, performance management is associated with the implementation of National Alignment Program (NAP) and Strategic Plan (SP) which represents an attempt to introduce ‘management for results’ into Brunei public administration. They are, according to the government, designed to enhance the coordination and collaboration among ministries and departments concerned and aligned to the national vision. One consequence of this adoption has been an increased concern with reporting and accountability for results and performance as well as compliance with financial rules and procedures (Athmay, 2008). However, there is no conclusive evidence that legislating performance management has in any way led to the emergence and institutionalisation of a performance culture in organisations especially in the developing countries (Ingraham and Moynihan, 2003; Norhayati and Siti-Nabiha, 2009; Athmay, 2008). Performance management has emerged in the late 1980s in the context of economically developed countries (Dunleavy and Hood, 1994; Osborne and Gaebler, 1996; Ferlie et al., 1996; Hughes, 1995; Pollitt, 2009) and Athmay has commented that: while the western states have embraced these changes and reaped the benefits due to the well internalisation of the features of modern administrative system and the support of parallel development of rational thinking, other countries have encountered hurdles in their endeavor due to the weaknesses of the administrative systems, the lack of acceptable norms of behaviour and the disconnection between the modern administrative principles and the prevailing values of the society (2009: 798). In spite of that performance management still has been adopted by many other countries with rather different economic and political characteristics. This study is motivated by the desire to understand the importance and significance of NPM by looking from the context of Brunei Public Sector that is very different from its point of origin in Western countries. Moreover, very few researchers in Asian have examined the notion of public sector reform in the light of the NPM approach, especially in Brunei. Thus, this study also intends to fill the gap by taking a qualitative nature of study. This paper is concerned with how the introduction of performance management is translated into actions at the organisational level to respond the call for improving productivity performance in Brunei’s dual system of Western-style bureaucracy and a traditional monarchy. It hopes to investigate to what extent PM is institutionalised in the Brunei public sector, whether the PM has been institutionalised ceremonially or instrumentally. The paper is divided into several sections. The theoretical concepts are discussed in the next section. Is then followed by a brief description of the research methods employed, the case findings and lastly, the conclusions. 2 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 2.0 Theoretical concepts 2.1 New Public Management (NPM) and Performance Management (PM) In recent years, economic rationales have been driving management reform of public sector organisations such as new public management (NPM). NPM were first advanced in Western countries, but have been since picked up by many other governments including Brunei (Haji Saim, 2005; Athmay, 2008). The underlying assumption was that there was an increasing belief in the superiority of private sector management practices as claimed by Hood (1991: 6) in serve for efficiency: This [NPM] movement helped to generate a set of administrative reform doctrines based on the ideas of professional management expertise as portable, paramount over technical expertise, requiring high discretionary power to achieve results (free to manage) and central and indispensable to better organisational performance through the development of appropriate cultures and the active measurement and adjustment of organisational outputs. A shift to NPM has made performance management (PM) a key component of the public sector management processes to improve performance at all levels (Hood, 1991; Dunleavy and Hood, 1994; Araujo and Branco, 2009). Much has been written on the need to management performance, but approaches that share some core components: the greater emphasis on strategic planning, performance measurement (include performance indicators) and results-oriented objectives (Hughes, 1994; Araujo and Branco, 2009). These approaches focus on the need to improve public service performance through planning and control and with the emphasis on results. Armstrong and Baron (1998; 2005) point out, PM is an interactive system which integrates the need to achieve organisational objectives and the importance of the contribution of managers to their development through goal setting, thereby influencing individual motivation and commitment. As will be explained later, this model is similar to that implemented by the Brunei public administration through the National Alignment Program (NAP) and Ministerial Strategic Plan (SP). Gray and Jenknis (1995: 75) suggest that implementing ideas of NPM would represent a critique of traditional public administration. Introducing NPM ideas would represent a fundamental change in the institutional framework of the public sector that alters the norms, values and beliefs prevailing in the traditional system (Osborne and Gaebler, 1992). NPM also has an impact upon structures and operations that alters the public sector’s internal management ‘paradigm’ in its search for better performance (Osborne Gaebler, 1992; Hood and Dunleavy, 2004). Reforming the public sector according to NPM is not a minor task. Empirical findings indicate that new practices in public sector organisations can be a variety of roles: ranging from a very limited to a constitutive role in management decision making. It is due to their origins that NPM give rise to a tension between public and private sector methods (Radnor and McGuire, 2004; Ferlie et al., 3 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 1996). For example, study by Hassan (2005) and Nor-Aziah and Scapens (2007) have showed that their reform failed and met with resistance that the commercial orientation culture failed to challenge the traditional institution. Siti Nabiha and Scapens (2005) have also shown that introduction of new KPIs for managing performance was resisted; although there was some formal change, the way of thinking remained the same. At present, although it is evident that features of PM are in use in Brunei via the Ministerial strategic plan, to what extent that is effectively being carried out by the organisation is still questionable. Public sector organisations, because of government reform initiatives, have to respond to this pressure. Ferlie et al. (1996) however argue that NPM is not a simplistic big answer. Rather it is a normative reconceptualisation of Public Administration whereby Lane (1995: 2579) has pointed out it is driven by ‘an intense search for new institutions that are more conducive to efficiency’. Thus it makes it important to study the nature of performance management in the Brunei public sector organisations. Next is the discussion of the theoretical lens which is being used to inform the case findings. 2.2 Institutional Theory as an Analytical Lens Institutional theory is concerned with understanding organisations within larger social and cultural systems (Oliver, 1991; DiMaggio and Powell, 1991). It focuses on the importance of social culture and environment on control and accountability practices. Institution is understood as a social phenomenon that constrains the behaviour of members of a given society through various mechanisms. As noted by Berger and Luckmann (1967: 52), ‘institutions by the very fact of their existence, control human conduct by setting up predefined patterns of conduct, which channel it in one direction as against the many other directions that would theoretically be possible’. Berger and Luckmann (1967) considered institutionalisation as a process by which something becomes acceptable over a period of time. Burns and Scapens (2000) state that the new PM practices and emerging routines can be said to be institutionalised when they become widely accepted in an organisation and become the unquestionable form of management control. However, Araujo and Branco (2009: 560) claim that organisations have set of rules and routines that define legitimate participants and agenda, prescribe the rules of the game and create sanctions against deviations as well as establish guidelines for how the institutions may be change (Olsen, 1991). 2.3 Path Dependency: Incremental Change Thus, in this study, it invokes the notion of path dependency to theorise the institutionalisation of PM system. Path dependencies are related to historical, political and institutional factors that constrain and mediate the choice and implementation of control practices (North, 1990; Burns and Scapens, 2000). Wilks (1997: 9) suggests that organisations develop according to an inherited code which ‘is made up of ideas, the legislation and the priorities which prevailed at the point of birth’. In other words, there 4 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 are institutional features that both persist over time and reproduced. To Peters (1999: 65), path dependence means that change and evolution will be constrained by the formative period of institutions, while North (1996: 99) equates it with an incremental change in institutions and the persistence of certain patterns. It can be expected to see a path-dependent sequence of changes as one that is tied to previous decisions and existing institutions. Inducements to change from external sources are received and adapted by the organisation according to its existing patterns or genetic code. It is argued that adjustments in preference and attitudes are constrained by prevailing institutional structures within a range of possible alternatives. Thus, it can be said that change and continuity are part of the same process. March and Olsen (1989: 168) argue that organisations ‘embed historical experience into rules, routines and forms that persist beyond the historical movement and condition’. It recognises that an absolute change is rare unless a strong force can push the existing path onto a new path (Mahoney and Thelen, 2010; Hall, 2010). Thus, the relevance of using path dependency is to understand that the institutionalisation of performance management is likely to be incremental as one would expect to find a permanent pattern or culture which is preserved within organisational procedures, forming and shaping their future course. Since public administration in Brunei also represents a traditional monarchic bureaucracy despite its modernism (Haji Saim, 2005; Athmay, 2008; Low, 2011), this approach seems to be useful approach to analyse the implementation of National Alignment Program and strategic planning on Brunei public organisation. 2.4 Performance Management as a Rational Myth Another important concept in the institutional theory is rational myth. To reform according to government reform initiatives, organisations commit to what is called ‘rational myth’ regardless of the existence of specific activities in an organisation (Tolbert and Zucker, 1994) such performance management. Meyer and Rowan (1977: 340) suggest that: Organizations are driven to incorporate the practices and procedures defined by prevailing rationalized concepts of organizational work and institutionalized in society. Organizations that do so increase their legitimacy and their survival prospects, independent of the immediate efficacy of the acquired practices and procedures. In this sense, PM function as powerful myths that spread through an organisational field (Meyer and Rowan, 1991) as there is belief that adopting such practice can secure legitimacy for the organisation. Aldrich and Fiol (1994: 1648) talk about legitimacy in terms of accepting a venture as appropriate and right given law. For example, in Brunei, National Alignment Program has been mandated by the government to implement performance management in the public sector organisations. Conforming to the expectation of the constituents by adoption some rationalised institutional myths enable 5 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 to make organisations seem natural and meaningful and hopefully, to secure vital resources for long-term survival (Aldrich and Fiol, 1994; Meyer and Rowan, 1991; Suchman, 1995). Thus, these collective beliefs not only constitute ‘social reality’ that define legitimacy, but it create new institutional logics which are available for the organisations and individuals to elaborate in order to appear legitimate (Friedland Alford, 1991: Dambrin et al., 2004; Haji Saim, 2005; Zilber, 2002). For this study, performance management practices are treated as new institutional logics or rules introduced in the context of Brunei. So it is expected that organisations can be shaped according to the new institutional logics (PM practices and procedures) that are imposed on them and the expectations of the environment (DiMaggio and Powell; 1991; Meyer and Rowan, 1977: 340) to win legitimacy. However, taking in the view from path dependency, undoubtly, the Brunei public sector has already established its set of institutional logics or rules (traditional rules and regulations) of managing its performance over the time. With this respect, Zilber (2002) argue that organisations may change or develop new structures as their enactment to comply with the rational myth, but it may not ensure the smooth and effective operation as it is just a way of signaling compliance. It is assumed that traditional rules and regulations still exercise an important influence on central government operations. This could result in a rather paradoxical situation where inconsistent (contradictions) logics of control operate simultaneously. In this perspective, PM practices may be decoupled from the actual technical and administrative processes within the organisation as they are viewed as rationalisations in order to achieve legitimacy (Dillard et al., 2004). 2.5 Institutional Contradictions: Decoupling Major implication derived by Meyer and Rowan was that while formal structures of organisations reflect the myths of their institutional environments to gain legitimacy, the relationship between actual work and formal structures may be negligible (Meyer and Rowan, 1977; DiMaggio and Powell, 1991). Formal organizations (practice) are often loosely coupled (or decouping) structural elements are only loosely linked to each other and to activities, rules are often violated, decisions are often unimplemented, or if implemented have uncertain consequences (Meyer and Rowan, 1977: 342). There is a tendency that institutional pressure and the organisation’s activities would contradict. Decoupling is thought to be essential to resolve conflicts between the two pressures (Meyer and Rowan, 1977; Oliver, 1991) and is a consequence of the need to conform to institutional expectations (NorAizah and Scapens, 2007; Norhayati and Siti Nabihah, 2009). In their study, Nor-Aizah and Scapens (2007: 235) have indicated the consequence of the loosely coupling in four ways; 1) the persistence of prevailing institutions; 2) ceremonial and low acceptance from the organisational members; 3) lack 6 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 of cooperation and integration between functional groups; and 4) organisational stability: gap between intentions and actions. Dambrin et al. (2007: 176) identified that there are two types of adoption of institutional rules. On one hand there is the active adoption of a practice which occurs when implementation (in behaviours and actions) and internalisation (when the employees view the practice as valuable and become committed to practice) are completed. In the opposite hand, there is minimal adoption of practice. This means when implementation occurs without internationalisation and practices are adopted on a ceremonial basis (Meyer and Rowan, 1977). This is when decoupling happens. In this case, suboptimal performance results may not only be accepted but also preferred (DiMaggio and Powell, 1991). Oliver (1991) claims that organisations are not simple receptacles for institutional norms that they have a strategic capacity to react. For instance, Townley (1997) shows that setting up performance appraisals (a rational myth) in universities in the United Kingdom depends on the capacities of those universities to challenge the legitimacy of such measures. Burns and Scapen (2000) have also stated not all organisations and actors may consistently pursue rational choices and they can usually give reasons for their action. 3.0 Methodology: A Qualitative Case Study A qualitative case study method is employed in this research as it allows an in-depth understanding of the ways in which PM is used within the organisation. This type of study provides rich description of the present situation (Punch, 2008; Collis and Hussey, 2008) in terms of the organisation’s policies and strategies regarding PM and get the ‘feel’ of what people think about PM and what it has done for them while taking into account historical aspects such as the administrative context that can make valuable contribution to themes which may be explored. The researchers therefore approaches the data from a socially constructivist position ensuring that the data are well-grounded and could offer rich descriptions from which explanations might be identified that were associated with the institutionalisation of PM in the case organisation within this cultural context. Case study data was collected between in March 2012 and primarily consists of 18 semi-structured interviews and archival sources such as reports and internal planning documents and reports of key performance indicators. Through this case study, it can be seen why and how performance management was endorsed, but nevertheless they continued to (re)embed the existing meanings, norms and values within the organisation. However, there was limitation on data collection. A longitudinal study could not be conducted to observe the historical events. Nevertheless, a reflective approach was used, by asking interviewees to explain and reflect upon the past events of PM process. It has also need to be taken into account that memories can be partial and may be shaped by present viewpoints. Hence, multiple data sources were used 7 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 (Nor-Aziah and Scapens, 2007; Saunders et al., 2009). The case findings and discussion are in the following section. 4.0 The Background to Brunei Public Administration Brunei Darussalam is a small country with a population less than 400,000 and an area of 5,765 square kilometres located on the island of Borneo in Southeast Asia. The administrative system in Brunei Darussalam is a combination of Western-style bureaucracy and a traditional monarchic system. The bureaucratic practices began with the Treaty of Protection in 1906 between the Sultanate and the British Crown. Apart from being the traditional monarch, the Sultan of Brunei is also the Prime Minister, the Minister of Defence and the Minister of Finance. The bureaucratic model was adapted to the monarchic tradition right from the start. The 1959 Constitution preserves the concept commonly referred to now as the ideology of the Malay Islamic Monarchy or Melayu Islam Beraja (MIB) (Law and Cheng, 2008, Haji Saim, 2005). As part of a closely-knit society, Brunei public administration is deeply influenced by its national culture and being small sovereign state, Brunei has a unique culture in terms of its socialisation. The economy of Brunei has been primarily dependent on the hydrocarbon sector. Since its independence in 1984, the government of Brunei has made economic diversification as its prime economic agenda to decrease its heavy dependence on oil and gas industry (Haji Saim, 2005; Bhaskaran, 2010; Athmay, 2008; Siddiqui et al., 2012). The country has outlined National Development Plans that identifies national vision, ‘Wawasan Brunei 2035’. To meet the development objectives of the country’s vision, effective governance institutions and government machinery are vital. The government’s point of view, a new institution would possess far greater capability to support the nation’s diversification programs. Due to the government’s concern for promoting accountability to assist the progress of diversification (Bhaskaran, 2010; Mohd Jamil, 2007), it has attempted the Brunei government to use legislation to foster the needed performance or result-oriented culture by introducing National Strategic Alignment Program (NAP) in 2003. The 2003 National Alignment Program (NAP) was an initiative to revive the orientation (performance culture-oriented). The focus is to enhance coordination and collaboration among ministries and departments and examine and drive all of them towards the national vision via producing strategic planning. The speech of the Sultan (titah) on 15th July 2003 has mandated this practice to become incorporated: Among the efforts that have been introduced recently, is the alignment program (NAP), where each of the ministries and government departments to provide strategic planning so that their organisational efforts implemented by the organisations will gain is adjusted by intentions, visions and aspirations outlined. 8 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 In the Brunei context, PM is thus associated with strategic plans, balanced scorecards (BSC) and key performance indicators (KPI) to measure organisational productivity or goals. The performance management tools being practised in many government organisations did not exist in Brunei until early 2003. Nevertheless, it should not be assumed that there was no system of measuring organisational performance. During this period, organisational performance is assessed through annual reports and individual performance is assessed through the performance appraisal. 4.1 The Implementation of Performance Management (PM) in the Case Study Organisation: Ministry of Defence (MINDEF) The Ministry of Defence (MINDEF), one of the thirteen ministries in Brunei, is known to be the first government organisation to implement PM practices. In pursuit of improving accountability and becoming more efficient, the Ministry has responded to both NAP and the Sultan’s titah (speech that become a decree) by introducing its first MINDEF strategic plan. As commented by the Ministry’s former Permanent Secretary: Modernising the Government with the purpose of ensuring good governance is always the top agenda in His Majesty’s Government (as stresses in his titahs). Our (the Ministry) contribution… is our own programme to modernise…. (via) Defence Strategic Plan. .. stresses the need for a proper management framework in continuously enhancing towards achieving a high performance organisation (Ministry of Defence Strategic Plan, 2003: 6). After its first Defence’s Strategic Plan in 2003, the Ministry has introduced several plans in 2005, 2008 and 2012 respectively. From this view point, the Ministry was conforming to the expectation of the external pressure by producing a strategic plan (a rational myth) that would enable the organisation to gain legitimacy (DiMaggio and Powell, 1991; Aldrich and Fiol, 1994). Throughout the strategic plans, there are vocabularies with concepts that are in line with new public management ideas such as ‘results’, ‘performance culture’, ‘value for money’, and ‘performance budgeting’. This shows the Ministry’s attempt to introduce the new institutional logics based on PM in the organisation. However, the Ministry’s dominant institution is very similar to the institutions prevailing in the organisations studied by Nor-Aziah and Scapens (2007) and Norhayati and Siti-Nabihah (2009) that is the public service orientation. The Ministry has featured a bureaucratic organisation that has layers of management, lacks of measurement culture and adopts traditional system of accountability. These features are the inherited genetic code resulted from the administrative system that has governed the organisation for past 29 years. There is path dependency in an organisation which shows the reproduction of these characteristics. In a later section it will show that despite the external pressure, the PM formal practices are being decoupled from the organisational activities. This implies that the existence of formal rules and procedures of PM are for ceremonial purposes only. 9 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 4.2 Conforming to Rational Myth: Performance Management System The external pressure from NAP has brought some changes to the Ministry. In 2004, the Ministry established the Office of Strategic Management (OSM) and also adopted BSC framework for its performance management system. The establishment of OSM is to develop, implement and monitor the PM system based on the BSC framework that emphasises performance indicators. The adoption of BSC was deemed rational by the Ministry as the technique appeared to be the ‘new’ prescription to public sector reform as mentioned in the first Defence strategic plan: MINDEF will be using the Balanced Scorecard as one of the several tools to ensure the business of Defence is operating and delivering results as effectively and efficiently as possible for assessing and measuring performance (Defence (first) Strategic Plan, 2004: 7). Siti Nabiha and Norhayati (2009) suggest establishing OSM would give new orientation to the Ministry. The PM process is made up of three stages as shown in Figure 1; setting the departmental strategic map, monitor the performance and performance assessment. Figure 1: The Ministry’s Pm Cycle Setting the departmental map and objective Monitoring Performance Stage Performance assessment stage Source: Author Another initiative taken to assist the PM process was the formation of a Strategic Management Group (SMG). The members of SMG are directors of departments all the way up to the Deputy Minister of Defence and all are to meet regularly to discuss strategic matters. Some interviewees have referred SMG meeting as: 1) ‘a way to meet key people in the organisation and to discuss together’; 2) ‘faster decision making’ and 3) ‘help to understand each other (departments) better (improve coordination)’. Tolbert and Zucker (1994) and Pollitt (2009) state that the process of institutionalisation of PM system in an organisation would involve new structures, processes and roles that would challenge the existing values and norms embedded in the organisation. With this respect, the management of the Ministry was taking the NAP reform quite seriously by introducing new initiatives to ‘get the house in order’ for its PM implementation. The 10 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 reason for this could be that all ministries need to show their ministerial (KPI) results at NAP symposium and to appear legitimately successful the Ministry must perform. Committed in institutionalising PM, the Ministry started to hiring a series of international consultants since 2004 to assist with its strategic review, in terms of setting strategy, BSC, departmental KPI and so on. However, according to Siti Nabihah and Scapen (2005), if the PM system does not challenge enough the existing values and norms, some elements of stability should be expected even when some form of change takes place. For example, formal rules concerning the settings of KPIs for the departmental were established for the implementation of the PM. However, not all formal rules and written procedures are followed, and to certain extent PM is being resisted: Where we are now, we are very much free from BSC [At the time of the study, PM activities were put on hold as the Ministry was reviewing their objectives and goals]. The nightmare is out since 2009 and now it just comes around… it [PM/BSC] does not help at all. It is just another burden. Every week you sit down (in SMG meeting) looking at colours [traffic light systems to show progress] whether you are green [achieve target], orange [needs improvement] and red [fail]… and then what do we have to do about this?... (of course) we want to make sure that we are doing the KPIS (as stated) in the White Paper (including strategic plan). We have mapped it out properly… but what turn out from day one to next hundred day is that we are not doing it… that is the problem, no implementation (Interview Senior Manager,19). PM has come to be perceived by the interviewees as an imposition by the management. The management adopted an authoritarian style which reflects a traditional form of organisation despite the introduction of PM. It was characterised at that time of the study as high formality, high power distance and deference to seniority (Blunt, 1988; Chan and Pearson, 2002: Low, 2011). The interviewees in the Ministry used a framing that gave greater emphasis to obedience to hierarchical authority and see PM as a duty rather than a valued tool. As a result, it has become a rather negative perception because meeting the expectation of SMG appeared more important (to make sure that all KPIs achieved) than the actual performance outcome, for example: They will report green [KPI achieved]… and everybody will be happy [but] they are missing the point. This SMG meeting literally got the wrong idea what you would be what when they see [KPI in] red [fail] or green. It is not reporting of performance, this is a management of performance (Interview with Manager, 12). Maintaining the appearance of deference towards the hierarchy has become the main concern. Behn (2005) argue that using top-down authority to impose PM is to create obedience and conformity, not to elicit discernment and adaptation. In this sense, the PM tool has turned into a tool which many objective owners feel as ‘witch-hunting’. This is whereby Bourne et al. (2002: 1299) and Neeley and Bourne (2000: 5) claim that people will feel threatened and may not support such system when they believe the 11 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 system will be used as a ‘big stick’ to chastise them. This, thus, explains the influence for a satisfying behaviour rather than optimising performance (Bourne et al., 2002; Fryer et al., 2009) as seen from the quotes below: This is nowhere near (good) management tool… people are scolded (for getting Red KPIs)… so we have to make sure for the next SMG meeting, all (red) KPIs turn from amber to green (achieved/passed). I would to say them (subordinates) ‘I don’t know how you want to do it, but you better run it to green next month’… it is not a function that supposed to drive our performance today (Interview with Senior Manager, C1.18). Because they want to show they are good (green KPIs), some have come to me asking if they can adjust the results [prior to SMG meeting]… it shows that they are afraid to show their true performance [...] so how would the top management know about the real situation? (Interview with officer, 2). Looking it this way, PM does not really support the performance. Rather, the compliance culture seems to give the idea of those who are not complying with achieving target would be punished. The reason being is that the ministerial PM process focuses primarily on organisational performance without a strong link to the individual performance level via the appraisal system as seen from Figure 1. Thus, the absent of reward system has linked the PM process to punishment, for instance: People are quite happy (when they reach their targets)… because it is quite rewarding already that they are not being scolded… you don’t want to be put in the spot light (in the SMG meeting for not having green KPIs) and that [not getting scolded] can just make your day (Interview with a senior officer,1). In this case, it could be argued that there is rhetorical commitment to PM as the emphasis is to ensure the KPIs appear green as achieved in the SMG meeting. This also confirms the study conducted by Blunt (1988) and Haji Saim (2005) that Brunei has ‘low uncertainty avoidance’ culture. Low uncertainty avoidance reflects the extent to which individuals attempt to cope with anxiety by minimising uncertainty. This again confirms to have affected the dynamics of SMG meetings. For example, instead of being instrument for reflection on and dialogue about strategic decisions, it has become rather a forum for check and balance. There was no clear evidence that it was used significantly to help improve the organisational performance but was rather framed in terms of monitoring. Like the findings from the study by Radnor and McGuire (2004: 255), the role of the senior officers seemed only like an administrator chasing performance data and monitoring the progress of tasks. In some instances, respondents presented a view where they defined themselves as an ‘order-taker’ that had no involvement or decision making in the PM system and appeared to display an ‘external locus of control’ despite their relatively senior position because of the hierarchical nature: 12 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 The one who manage is OSM. They have a say whether we can do it or not (31.55). We have argued like’ why we are measuring this and that’, but in the end we give up like ‘okay, just to satisfy them [OSM/top management] and others have started doing it, we can’t hold it any longer and argue anymore’… [I feel] The measurement does not meet the real objective, like… are we measuring the right impact to the Ministry. I feel what we measure do not have great impact to the client (Interview with a Senior Officer, 9). 4.4 Performance Management Are Decoupled from the Ministries Activity PM process appeared to be an ‘addition’ to an existing structure rather than a core driver to other aspects of organisation. Not all members understand the concept of PM; the respondents have claimed training of PM was almost none. PM processes may be adopted ceremonially by the Ministry as there is a clear directive from the government to adopt the system. This thus suggests that in certain cases, what the organisation should accomplish has little relevance to the actual work that is actually performed as illustrated expressed by this interviewee: You have to do your ‘must-do’ work on one hand and this KPI on the other hand. But this (doing KPI) does not go into my appraisal. This [KPI] task is just a sideline. this will be my second priority. This [KPI] is not what I’m supposed to do… If I don’t finish my papers (core job), I will be in trouble. But if I don’t finish this [KPI], people might understand because that is not my core job. That is the mentality… although that is why KPI is not moving forward (Interview with an officer, 10). Despite compliant culture that the ministry has developed, cascading of PM has appeared poor whereby some respondents claimed that they were not exposed to this system, for instance: One day [this year], my colleague is printing papers out and sticking them together. I asked ‘what is this?’ and she said ‘this is our KPI’. So that was the first time I’ve `heard about KPI from this deaprtment. While sticking them together she also said ‘by quarterly we need to finish two/three papers’ and stick it on the wall. That’s the furthest the discussion went. It was just describing those things… It’s rather like a coffee table talk rather than guidance. We are not walking towards that direction, we are more like working to meet ad hoc deadline. […] I’m not aware about KPI at corporate level. It’s never mentioned so far that I’m here (Interview with an officer, 3). In 2005, I noticed that senior managers were going for KPI meetings… but we were never exposed to it. I only came to know about KPI when I moved here. It was when the ex-director was still here… then again, I still have any idea about KPI. We hardly talk about KPI. Our routine job has occupied us 100%. We don’t have time to touch on something else… (Interview with manager, 7). 13 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 Also, most of the respondents of lower management do not feel identified by the PM system. As expressed by a member who is tasked to do KPIs: This [KPI] is not what I’m supposed to do… but if I don’t finish the papers [core job] may be I will die… something like that. What I mean is… I will be in trouble. If I don’t finish this [KPI], people might understand because this is not my core job. That mentality… although it is wrong, it is the mentaliy…. That is making KPI not moving forward (Interview with an Officer, 10). Since the KPIs were prepared in a top-down approach, the measurements were not considered by managers as relevant to their operational activities. Hence, the perceived mismatch between everyday practices and the PM seems to confirm Siti-Nabiha and Norhayati (2009) view that performance measure externally imposed can prove unfavourable to the primary needs of the organisation. In many countries where PM has been introduced, cultural change has been regarded as one of strategies to support its practice (Kennerly and Neely, 2002: 1236). Almost all respondents in the senior position perceived that the Ministry’s underlying culture as a major barrier to the use of the PM system. In particular, the strong emphasis on the notion of hierarchical authority, as exposed in earlier accounts above. The emphasis on the legalities or on organisational control tends to mean that the minimal acceptable standard for quantity and quality of performance become the maximal standard in practice (Katz and Khan, 1978: 408-409). Ever since the PM system was introduced, one head of division said that: I don’t think it has changed anything. I might be wrong… but [KPIs] figures have not changed. […] I don’t think performance has changed. Performance stays the same, but the level of transparency has improved… the sharing, the approach to the problem has improved… but not performance wise (Interview with Senior Manager,19). The quote of ‘performance stays the same’ explains why some target does not change for several years. It shows that they are still following the KPIs of the previous years. There are a number of strategic plans that have been introduced which by right would influence the performance targets or the departmental KPI, but this is not really practiced because the informal rules remain unchanged. For example: This [KPI] was updated March 2011. It was not much different with the previous print. We are just rephrasing it like ‘how do you want to do it? Annually? Quarterly?’ The recent one we changed it to (measuring) KPI quarterly. The main thing, there is not much difference from the last KPI (Interview with an officer, 10). The ceremonial structures that are displayed to accommodate the PMS may not be able to explain the actual performance of the organisation. If that is the case, lose 14 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 coupling exists in the organisation, it is difficult to justify how PM could be a better accountability system (Norhayati and Siti-Nabihah, 2009: 249). Meyer and Rowan (1991) and Collier (2001) explain that decoupling emerges to accommodate institutional demands and operational demands. In this Ministry, the PM was enacted but not fully as intended as there was a gap as identified by Nor-Aziah and Scapens (2007). In this sense, the role of PM in the Ministry as accountability is not internalised (Dambrin et al., 2007) as a source of decision-making. The issue of legitimacy seems important for the Ministry (Suchman, 1995; Meyer and Rowan, 1991) that BSC and KPI are appear to be the rationalised myths that the Ministry might adopt to achieve it. 4.5 Path Dependent Influence the Institutionalisation of Performance Management The formal rules and informal routines shape the institutionalisation of PM in the Ministry. It seems to appear that the Ministry did not break away from its traditional pattern which is line in the classical bureaucratic form. The informal outlines and bureaucratic work were unable to follow the pace of change. The Ministry collectively was unprepared for the implementation of the PM from many aspects, including the main administrative and legalist culture persists within the organisation. Conflicts between actors’s rationalities can impede the institutionalisation of PM (Townley, 1997). Despite the myth of PM, rules and regulations still exercise an important influence on government operation (Modell et al. 2007). Although the internal changes in the Ministry driven by the introduction of NAP are noticeable, the PM process is severely constrained by the established procedures and rules. Not all management systems in the civil service were reviewed or updated to well-suited with performance management. It seems like the implementation of PM system has not been tightly coordinated and integrated with other management systems such as budget and performance appraisal. The general underlying assumption is that if there was link between these other management systems, it would lead to such voluntary changes which involve in a change informal routine. But that is not the case: Sometimes when we discuss about performance in our meeting, it is easy to identify what the problem is… it’s all about budget. It is easy to identify what is the problem. You can do things (to achieve targets) because (not enough) budget… so… ‘stop talking and give me money’. It is simple as that, but somehow it doesn’t work that way… all this BSC and KPI…. Although its there, it doesn’t work if you don’t utilize it to give make decision or give the right resources that they need…. That makes strategic meeting even worse. What’s the point of talking? (Interview with Senior Manager, 19). In fact, NAP and strategic plan, as rationalised myths, were actually designed to complement the budget process (ACCSM, 2005; Athmay, 2008). Unfortunately, there is no link between strategic plan and the budget system. As Athmay (2008) has pointed out, budgetary process in Brunei is still very much oriented to the traditional concern with financial control and compliance with rules and regulations. Brunei has still kept its 15 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 golden rule which was established in 1983. This unfortunately affects the achievement of targets: I don’t think our budget has changed that much… this means that the budget becomes smaller as the Ministry is growing. Every year, we have to increase our spending by this much, but the budget amount stays the same. Hence, the budget is not catered for (Interview with Senior Manager, 19). In effect, the strategic plan in itself is simply just a check-list despite the Ministry is subject to supply reliability measures as indicators. With regards to inability to take action, this is because as one of the public administration subset, the Ministry is still very much dependent on the whole administrative rules and regulations, such as General Orders (GO) 1961 and Financial Regulation which were established long time ago are retained until today. This also gives the idea why some objectives and KPIs could not be met: We are using government procedures such as General Orders 1961and Financial Regulations […] BSC and KPI as management tools… Don’t really reflect in the appraisal and budget system… the system should allow some flexibility for the KPI to work really well... able to take action. You do take action, but results? It is still questionable, what more if you involve (government) money… budget is not controlled by the Ministry… so how can you ensure that what you need will be available as soon as possible? It is very difficult (Interview with Senior Manager, 8) This appears to confirm the Merton’s concept of goal displacement and Blau’s concept to work to rule (Burrell and Morgan, 1979), patterns that are commonly found in a bureaucracy. Moreover, the reward system (performance appraisal) is not linked to the PMS when giving salary increments, bonus or promotion. Bonuses are given to all employees irrespective of individual performance. In this sense, the PM system in the Ministry does not link with their own personal goals (Armstrong and Baron, 1998; Mohd Jamil, 2008). This again highlights that cultural heritage that has been reproduced and preserved through routines and norms in line with path dependence behaviour that is embodied in the culture of the organisation. For instance, a quote from a ‘new blood’ member to the Ministry expressed: I wasn’t involved in [KPI] or even brief about it. Even if I see it and agree to it, I still don’t know… don’t see the point because I don’t identify with it. If you tell me to do [according to KPI targets]… I still have questions what sort of work? If my senior doesn’t bother to tell or help, I don’t see the need [to obliged] for me, I wasn’t measured by this… I’m measured by how I please my boss (Interview with an officer, 3) The nurturing of these attitudes must aim at inculcating the philosophy of professional development and the underlying values of the need to strengthen the linkage between performance appraisal and professional development (Mohd Jamil, 2009: 45). 16 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 5.0 Conclusion NAP has become the rationalised myth that government ministries in Brunei have to implement to performance management (PM) to gain legitimacy (Meyer and Rowan, 1996). The myth have evolved within the Ministry, resulting in the belief that its response to the pressure that are aimed at efficiency when in reality they are aimed at achieving legitimacy for the organisation. Despite the new rules and procedures introduced in the Ministry, the habits and informal routines have told a different story. In essence, the empirical findings have shown that the change only occurred on the surface implying that the PM is institutionalised ceremonially. This is similar to several studies (such as Dillard et al., 2004; Siti-Nabihah and Norhayati, 2009; Nor-Aizah and Scapens, 2007), in order to for organisations be viewed as legitimate (or rather successful) organisation in their field, it would led to the ceremonial use of PM system. The PM system was introduced without seriously challenging the prevailing institutions or the interpretive scheme (beliefs) of the organisational members. The PM system in the Ministry has proved decoupled with other management systems at the administrative level, despite the government’s intentions to reform. This subsequently has paved way for path dependency in the change process which has preserved the traditional features such as management style, rules and regulations and personnel management that do not seem conductive to the application of PM tools As explained above, the notion of path dependency provides a means of theorising for such difficulties. In developing its PM system, some basic tenets of PM have been deemphasised in the process, for example, the absence of the reward system in the PM process give rise to a compliance culture through ‘soft punishment’ (being chastise for not doing it) and no full integration for other management systems. It is, thus, deemed unsuccessful to alter the culture or routine of the Ministry to any appreciable degree which resulted in the limited application of the PM into activities of the organisation. This refers to what have been said by DiMaggio and Powell (1991), reform is like ‘new iron cage’ because this is just a result of conforming to rationalised myth without necessarily making the Ministry more efficient. As Siti Nabiha and Norhayati (1994) and Ferlie et al. (1996) have questioned it, to what extent that new public management (NPM) are truly new rather representing old wine in new bottle. Change seems necessary by adapting to the rational myth in order to maintain the stability of the organisation yet to be seen legitimate within the organisational field. Rationalised myth did bring change into the Ministry, but dominant culture has prevailed in maintaining the status quo. As Burns and Scapen (2000: 21) conclude in their studies, ‘much would happen, but all would be play-acting’. At the point when the research was about to end, the Office of Strategic Management (OSM) was in the process of revamping or improving their strategic plan and its processes. It is interesting to note that, the Ministry is still in the process of changing even though the question still remains as to what extent it would transform. 17 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 6.0 Acknowledgements Last but not least, I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to my supervisors, Dr. Paul Tosey and Dr. Alexandra Bristow, for their guidance and support. Reference Armstrong, M. and Baron, A. 1998 Performance Management: the New Realities, London: The Cromwell Press. Aldrich, H. and Fiol, M. 1994 Fools Rush in? The Institutional Context of Industry Creation, The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 19, No. 4, pp. 645-670. Araujo, J. and Branco, J. 2009 Implementing Performance-based Management in the Traditional Bureaucracy of Portugal, Public Administration, vol.87, no.3, pp.557-573. Athmay, A. 2008 Performance Auditing and Public Sector Management in Brunei Darussalam, International Journal of Public Sector Management, Vol. 21, No. 7, pp. 798-811. Berger, P. and Luckmann, T. (1967) The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge, Garden City, New York. Bhaskaran, 2010 Economic Diversification Brunei Darussalam, CSPS Strategy and Policy Journal, Vol. 1, pp. 1-13. Behn, R. 2005 On the Ludicrous Search for the Magical Performance System, Government Finance Review, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 63-64. Bourne, M., Neely, A., Platts, K. and Mills, J. 2002 The success and failure of performance measurement initiatives: Perceptions of participating managers, International Journal of Operations and Production Management, Vol. 22, Issue. 11, pp. 1288-1310. Blunt, P. 1988, Cultural Consequences for Organization Change in a Southeast Asian State: Brunei, The Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 235240. Burns, J and Scapen. R (2000) Conceptualising management accounting: an institutional framework, management accounting research, vol. 11, pp. 3-25 Burrell, G. and Morgan G. 1979 Sociological Paradigms and Organisational Analysis, London: Heinemann Educational Book Ltd. Chan, C. and Pearson, C. (2002) Comparison of managerial work goals among Bruneian, Malaysian and Singaporean managers, Journal of Management Development, vol. 21, No. 7, pp. 545-556 Collins, J and Hussey, R. 2009 Business Research: a practical guide for undergraduate and postgraduate students, 3rd Edition, Palgrave MacMillan. Czarniawska, B. and Joerges, B. 1998 Travels of Idea in Czarniawska, B. and Sevon, G. (ed.) Translating Organizational Change, De Gruyter Studies in Organisation, New York, pp. 13-47 Dambrin, C., Lambert., C. and Sponem, S. 2007 Control and Change – Analysing the 18 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 process of institutionalisation, Management Accounting Research, Vol. 18, pp. 172-208. Dillard, J., Rigsby, J. and Goodman, C. 2004 The Making and Remaking of Organization Context: Duality and the Institutionalisation process, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability, Vol. 17, No. 4, pp. 506-542. DiMaggio, P. and Powell, W. 1991 Introduction in Powell W. and DiMaggio, W. (ed.) The Institutionalism in Organisational Analysis, The University of Chicago, Press, Chicago, pp. 1-38. Dunleavy, P. and Hood, C. 1994 From Old Public Administration to New Public Management, Public Money and Management, pp. 9-16 Ferlie, E., Lynn, A. Fitzgerald, D. and Pettigrew, A. 1996 The New Public Management in Action, New York: Oxford University Press Incirporation. Friedland, R. and Alford, R. 1991 Bringing Society Back in: Symbols, Practices and Institutional Contradictions in Powell W. and DiMaggio, W. (ed.) The Institutionalism in Organisational Analysis, The University of Chicago, Press, Chicago, pp. Fryer, K., Antony, J. and Ogden, S. 2009 Performance Management in the Public Sector, International Journal of Public Sector Management, Vol. 22, No. 6, pp. 478-498. Gray, A and Jenkins, B. 1995 From Public Administration to Public Management: Reassessing a Revolution?, Public Administration, Vol. 73, pp. 75-93. Hall, P. 2010 Historical Insitutionalism in Rationalist and Sociological Perspective in Mahoney, J. and Thelen, K. (ed.) Explaining Institutional Change: Ambiguity, Agency and Power, Cambridge University Press, USA, pp. 204-224. Hood, C. 1991 A public management for all seasons?, Public Administration, Vol. 69, pp. 3-19. Hughes, O. 2003 Public Management and Administration: An introduction, Third Edition, Palgrave, MacMillan. Haji Saim, S. 2005 The Administrative System of Brunei Darussalam: Management, Accountability and Reform, Brunei: University of Brunei Darussalam Publication. Kennerly, A, Adams, C and Neely, M. 2002 The Performance Prism: The Scorecard for Measuring and Managing Business Success, Pearson Education. Lane, J. 1995 The Public Sector: Concepts, Models and Approaches, 2nd Edition, London: Sage Publications Ltd. Low, K. C. 2011 Malay Leadership Style, the Brunei Perspective, Conflict Resolution and Negotiation Journal, Vol. 2011, Issue. 1, pp. 14-34. Mahoney, J. and Thelen, K. (2010) A Theory of Gradual Institutional Change in Mahoney, J. and Thelen, K. (ed.) Explaining Insitutional Change: Ambiguity, Agency and Power, Cambridge University Press, New York, pp.1-38. March, J. and Olsen, J. 1989 Rediscovering Institutions: The Organizational Basic of Politics, The Free Press, New York. Meyer, J. and Rowan, B .1977 Institutionalised organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony, American Journal of Sociology, vol. 83, pp. 340-363. Meyer, J. and Rowan, B. 1991 Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony in Powell W. and DiMaggio, W. (ed.) The Institutionalism in Organisational Analysis, The University of Chicago, Press, Chicago, pp. 1-38. 19 Proceedings of European Business Research Conference Sheraton Roma, Rome, Italy, 5 - 6 September 2013, ISBN: 978-1-922069-29-0 Mohd Jamil, A. 2008 Performance Management in the Brunei Civil Service: issues and Challenges, Civil Service Institute Journal, Vol. 18, pp. 30-46. Modell, S., Jacobs, K. and Wiesel, F. 2007 A process (re)turn? Path dependencies, institutions and performance management in Swedish central government, Management Accounting Research, Vol. 18, pp. 453-475. Nor-Aziah, A. and Scapens, R. 2007 Corporation and Accounting Change: The role of accounting and accountants in a Malaysian Public Utility, Management Accounting Research, Vol. 18, pp 209-247. Norhayati, M. and Siti-Nabihah, A. 2009 A Case Study of the Performance Management System in a Malaysian Government Linked Company, Journal of Accounting and Organisational Change, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 243-276. Neeley, A. and Bourne, M. 2000 Why measurement initiatives fail, Measuring Business Excellence, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 3-6. North, D. 1990 Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Oliver, C. 1991 Strategic responses to institutional process, Academy Management Review, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 145-179. Osborne, D. and Gaebler, T. 1993 Reinventing Government: How the Entreprenurial Spirit in Transforming the Public Sector, New York: Plume Book. Pollitt, C. 2009 Bureaucracies Remember, Post-Bureaucratic Organizations Forget? Public Administration, Vol. 87, No. 2, pp. 198-218. Punch, K. 2008 Introduction of Social Research, Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches, London: SAGE Publication. Saunder, M., Thornhill, A. and Lewis, P. 2009 Research Methods for Business Students, Fifth Edition, London: Financial Times Prentice Hall. Siddiqui , S., Athmay, A., Mohammed, H. 2012 Development and Growth through Economic Diversification: Are there Solutions for Continued Challenges Faced by Brunei Darussalam?, Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, Vol. 4, No. 7, pp. 397-413. Suchman, M. 1995 Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches, the Academy of Management Review, Vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 571-610. Radnor, Z. and McGuire, M. 2004 Performance management in the public sector: fact or fiction? International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, Vol. 53 Issue. 3, pp. 245-260. Tolbert, P. and Zucker. L. 1994 Institutional Analyses of Organizations: Legitimate but not institutionalised, VoL 5, Institute for Social Science Research, UC Los Angeles. Townley, B. 1997 The institutional logic of performance appraisal, organization studies, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 261-285. 20