Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference

advertisement

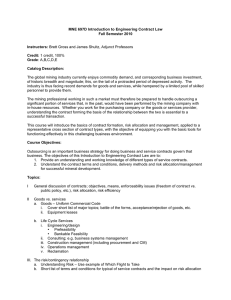

Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 Community Participation in Environmental Impact Assessment for Mining Projects in Selected Communities in Ghana Emmanuel Yamoah Tenkorang*, Hannah Owusu-Koranteng** and Richard Hato-Kuevor*** The potential contribution of mining to Ghana‟s economy was acknowledged and given priority attention under the Economic Recovery Programme/Structural Adjustment Programme (ERP/SAP) undertaken between 1983 and 1990.The accelerated growth in the mining sector under the ERP/SAP has led to Ghana achieving the status of the second largest gold producer in Africa after South Africa. This achievement notwithstanding, mining has had significant impacts on the environment, especially on biodiversity, air and water quality, pollution levels as well as land degradation and health. The EIA is now a prerequisite for securing a mining license, but practical weaknesses with the EIA process which deny the opportunity to participate fully, especially for affected local communities are also noted. The objective of the study was to assess communities‟ participation in the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process undertaken for mining operations. The study employed a descriptive design in an attempt to describe the reality of a situation as compared with what the law states. The study area consists of three large scale mine catchment areas: Birim North; Prestea-Huni Valley and Ellembelle District. Both purposive and convenience sampling methods were adopted to select required respondents for the study from two communities purposively selected in each of the three selected mining areas and three Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) in each of these communities. In total, there were 16 interviews and 18 focus group discussions. The study concludes that even though there were generally several different levels of meetings, the participation of communities was mostly limited to information dissemination and to a smaller extent consultation. This study recommends that the Government of Ghana through the EPA should ensure that the EIA process is more transparent than it is now. This can be achieved by for instance, ensuring that technical documents used as a basis for the organization of community meetings and fora are made available to the communities for periods adequate to allow for proper studies before the meetings and fora are organized. In addition, government through any appropriate agency and in consultation with affected communities should hire the services of consultants to act for and on behalf of the affected communities in negotiating appropriate redress for the environmental impact of mining projects in Ghana. _________ * Institute for Development Studies, University of Cape Coast, Ghana ** WACAM, Ghana *** Oxfam America West Africa Regional Office, Ghana Page 1 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 1. Introduction The potential contribution of mining to Ghana‟s economy was acknowledged and given priority attention under the Economic Recovery Programme/Structural Adjustment Programme (ERP/SAP) undertaken between 1983 and 1990. With the aim of increasing production and productivity of the mining sub-sector, changes were made in mining sector legislation to attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). This effort included increased fiscal liberation of the mining sector, the strengthening and reorientation of government support institutions for the mining sector and the privatisation of state mining assets (Akabzaa and Darimani, 2001).These reforms resulted in the expansion of the mining sub sector in Ghana. At the start of 2008, a total of 212 mining companies had been awarded mining leases and exploration rights (Minerals Commission, 2008 cited in Boon and Ababio, 2009). Sixteen percent of these mining companies were given mining leases by the Minerals Commission. As of 2009, Ghana had nine large-scale mining companies producing gold, diamonds, bauxite and manganese. There were also over two hundred registered small scale mining groups and 90 mine support service companies. Twenty four percent of all mining companies in Ghana as at the time were foreign controlled mining exploration companies, whilst the Ghanaian controlled mining companies, which constituted 60 percent of all mining activities, were mostly involved in small-scale mining and spread across the length and breadth of the country. The accelerated growth in the mining sector under the ERP/SAP has led to Ghana achieving the status of the second largest gold producer in Africa after South Africa and a significant producer of bauxite and diamond (Ghana Chamber of Mines, 2009). This achievement notwithstanding, mining has had significant impacts on the environment, especially on biodiversity, air and water quality, pollution levels as well as land degradation and health (Boocock, 2002). To make matters worse, some mining companies have even been granted mining leases to mine in Forest reserves in Ghana . Regardless of the location, large areas of land and vegetation are cleared to make room for surface mining activities, which is the predominant mining process in use in Ghana. Surface mines use their concession space for activities such as siting of mines, heap leach facilities, tailings dump and open pits, mine camps, roads, and resettlement for displaced communities (Akabzaa and Darimani, 2001). The negative impacts of mining are compounded by the fact that the mining industry has been a major perpetuator of the continuing marginalisation of indigenous communities, as this activity has alienated them from their land and livelihood resources (Aubynn, 1997). As Boocock (2002) argues, mining activities have had dire consequences on the environment and society and have negatively impacted the social and economic character of mining communities. Mining companies have also been accused of shirking their obligations to the communities in which they operate, thereby Page 2 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 increasing the level of local poverty and vulnerability. Notwithstanding the considerable benefits from mineral resources, a further issue is the “paradox of resource curse”; that is, though rich in mineral resources, the majority of the people continue to be poor. To illustrate, a 2008 UN Integrated Regional Information Networks (IRWN) report indicated that 12.8% of Ghana‟s 22 million people were deemed “extremely poor” by UN standards, as they live on less than a dollar a day, and struggle to access basic social services like health, water and education. Concerned about the paradox, human rights activists, civil society organizations, environmentalists, and government officials in and outside Ghana have been critical of mining and mineral resource exploitations and the lack of effort to develop the people and the local environment. Serious criticisms have been directed at foreign players who have been known to exploit legal loopholes and abuse both human rights as well as the environment. For example, the current mining law (most agitations are calling for its review) does not allow farmers enough say in authorizing their lands for mining activity, making it difficult to crack down on the rampant exploitation of the environment by mining industries. There is no doubt that it is the local people who bear the brunt of all the environmental degradation that accompanies mining operations. The nation as a whole gains disproportionately from the taxes of all types and dividends accrued from mining companies. No portion of this financial benefit is specifically allotted for the development needs of the degraded environment. There is a general belief in Ghana that poverty and lack of sustainable development in the mining communities and the country in general has been caused by the behaviour and operations of the mining companies. However, these companies have countered this claim by arguing that in a developing country like Ghana, poverty is generally pervasive, even in communities where there is no mineralization. The mining companies do not perceive their presence and operations in local communities to contribute to poverty and vulnerability. The Ghana Chamber of Mines (GCM), an association of all corporate miners in Ghana, contends that the social investments its members make in the mining communities are their contribution towards improving the well-being of the people and facilitating community development. The GCM also notes that most nonurban and non-mining companies do not benefit from these private sector contributions. Importantly, the GCM argues that mining companies should never be seen as surrogate governments; rather the efforts of the companies should be seen only as complementary to what government has to provide. Given the divergence of opinion regarding who is responsible for the current state of affairs, it thus becomes imperative to include all the stakeholders in the mining license “decision-making” and choice of technology for the mining project. All efforts to involve all stakeholders, issues of level of participation of each stakeholder, the conditions of participation and the media for interaction if appropriately considered and selected will foster transparency and government accountability and responsiveness. This is also Page 3 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 reflected in the Rio declaration, principle 10 which states: “Environmental issues are best handled with the participation of all concerned citizens at the relevant level” (WCED, 1992). To achieve mutual benefits, the impacts of the mining life cycle require the participation of both the mining companies and host communities in meaningful dialogue. The information communities need in order to participate in mining activity decision-making includes basic knowledge of the five stages in the mining life cycle: mineral exploration; deposit evaluation; mine planning; construction and operation; and mine closure reclamation. However, the reform in the mining sub-sector was done with little attention paid to reforming existing environmental laws to manage the environmental consequences. In 1989, the Environmental Protection Council began to apply the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) as an environmental management tool for industrial operations. The Mining and Environmental Guidelines, published in 1994 with the objective of assisting the mining industry to operate environmentally responsibly, was given a legal mandate in December 1994 when the EPC was transformed into the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) by an Act of Parliament (EPA Act, 1994 (Act 490) to empower it to enforce environmental laws in Ghana. With the passage of Act 490, it became mandatory for all new mining projects to prepare EIA, while existing mines were required to prepare and submit Environmental Management Plans (EMP). Legislative Instrument 1652 (LI 1652), Environmental Assessment Regulations, 1999 was passed to operationalise the implementation of EIA in industries that have either perceived or known impacts on the environment. The EIA process involves identification and quantification of environmental impacts. It also involves categorisation of impacts including direct, indirect and cumulative impacts. 2. Problem Statement The EIA is now a prerequisite for securing a mining license, but Akabzaa and Darimani (2001) note practical weaknesses with the EIA process which deny the opportunity to participate fully, especially for affected local communities. A major principle of the EIA process is that the proponent is required to give notice and advertise the proposal in the national press to enable the public to express its interest or concerns or to comment on the project. While at first glance this appears reasonable, the approach requires some scrutiny. Article 12 (k) enjoins the EPA to require, as part of the Terms of Reference (TOR) for the submission of an EIA, that the proponent consults with members of the public likely to be affected by the operations of the undertaking. However, the actual procedure for the consultation is not clear or outlined. This Page 4 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 therefore gives the proponent the discretion to decide the kind of community participation that will be used in the process. After a draft EIA report has been submitted by a proponent, the EPA is supposed to publish it in at least one national and one community newspaper in the locality of the proposed mining activity. The Agency is also supposed to make copies of the report available to the local community for review and comment, with the public having 21 days, from the first day of publication, to provide any such comments. This approach to public consultation is, however, problematic. For instance, the media of advertisement, primarily the national press or the premises of District Assemblies, are not very functionally accessible to these communities. Also EIA reports are presented in technical language, which is beyond the comprehension of the average community members preventing them from being able to raise concerns. Given these observations the question arises as to how the EIA in practice address the issue of community participation. The objective of the study was to assess communities‟ participation in the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process undertaken for mining operations. The study was done to answer the following research questions: i. What has been the practice of participation by communities in the EIA process? ii. What problems inhibit improved community participation in the EIA process? iii. How can community participation in the EIA process be enhanced to ensure environmental sustainability? 3. Environmental Impact Assessment Ghana, like any other country and especially developing ones, has had to exploit its resources to achieve development. However, the kind of large scale resource exploitation embarked upon by mineral rich countries has ignored environmental consequences (Mabogunje, (1980), cited in Ofori, (1991). However, after the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (UNCHE) of 1972, efforts at acknowledging the relationship between development and environment were given a boost with accounting for the environmental consequence of development effort forming a major component. While the Stockholm conference was important, subsequent environmental conferences, especially the Rio Conference of 1992 gave practical meaning to environment-development relationship. The protection of the human environment for the well-being of peoples and economic development was made a duty of all Governments. Developing countries were entreated to direct their efforts to development that bears in mind the need to safeguard and improve the environment and to improve the human environment for present and future generations (http://www.unep.org/Documents.Multilingual/Default.asp?documentid=97&articleid=150 3-). Page 5 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 The Environmental Protection Council (EPC) of Ghana was formed in 1973 based on recommendations of the UNCHE to advise the government on environmental issues. In 1981, the EPC submitted a memorandum to the Parliamentary Committee formed to draft a National Investment Code for Ghana on the need to include in the Code, provisions requiring investors to state the likely environmental effects of their investment (Ofori, 1991). In 1985, the 1981 investment code was abolished and replaced by Provisional National Defence Council Law 116 (PNDCL 116 of 1985). This law made the statement of the likely environmental consequence of investments a condition for the approval of any project. This law placed no specific responsibility on the EPC, but based on its own initiative, it coordinated activities with the GIC and the Ministry of Industries, Science and Technology to form a sub-committee of the Environmental Impact Assessment Committee (EIAC) of the EPC to draft EIA legislation for Ghana (Ofori, 1991). It is noteworthy that the practise of EIA then was for the proponent of the project to submit a statement on the environmental impact without clear provisions regarding the involvement of the people affected by the project. The National Environmental Action Plan (NEAP) was inaugurated in 1989 with a note that the EIA was to be as comprehensive as possible. This NEAP was to be coordinated by the EPC whilst the EIA requirement was still a responsibility of the GIC. Environmental Impact Assessment became integral to the consent process for major development projects financed by most International Finance Institutions (IFIs) like the World Bank and International Finance Corporation. Most applicants were also required to submit an Environmental Statement in support of applications for funds. The World Bank, for instance, effective 1st March, 1999, required the undertaking of an Environmental Assessment to be provided and reviewed for all projects to be funded by the Bank to ensure that they were environmentally sound and sustainable to improve decision making (World Bank, 1999). 4. Participation The definition of “participation” is a matter that has attracted a considerable disagreement among development scholars and practitioners (Cohen and Uphoff, 1980). The World Bank (1991) defines participation as mainly a process whereby those with legitimate interest in a project influence decisions which affect them. This definition of participation does not distinguish between collective and individual influence on decision-making. Others view participation as an instrument to enhance the efficiency of projects or as the co-production of services. Some would regard participation as an end in itself while others see it as a means to achieve other goals (Cohen and Uphoff, 1977). These diverse perspectives truly reflect differences in the objectives for which participation might be advocated by different groups. Page 6 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 Paul (1987) defines community participation as an active process by which beneficiary or client groups influence the direction and execution of a development project with a view to enhancing their well-being in terms of income, personal growth, self-reliance or other values they cherish. This definition reflects the broad nature of the process of community participation and the fact that interpretation is linked to an agency‟s development perspective. Community participation can be said to occur only when people act in concert to advise, decide or act on issues, which can best be solved through some joint action. The nature of the project and the characteristics of beneficiaries will determine, to a large extent, how actively and competently the practices of participation can be achieved. Further, it is useful to distinguish between various levels of intensity in community participation, though different levels of community participation may co-exist in the same project (Paul, 1987; Cohen and Uphoff, 1980; Oakley, 1991; Nelson and Wright, 1995). Paul (1987) identified four ascending levels of participation as information sharing, consultation, decision-making and initiating action. According to Paul, all four levels may coexist in a project. The first two categories present ways to exercise influence, which he terms low participation; the latter two offer ways to exercise control, which he sees as high participation. Pretty and Vodouche (1997) created seven categories describing participation, from least to most participatory. 1. Passive participation describes the type of participation where locals are told what is going to happen and involved primarily through being informed of the process. 2. Information sharing describes the type of participation where locals answer questions to pre-formulated questionnaires or research questions and do not influence the formulation or interpretation of the questions. 3. Consultation describes the type of participation where project beneficiaries meet with external agents who define both problems and solutions in light of the responses, but are under no obligation to take on people‟s views or share in decision-making. 4. Provision of material incentives involves project beneficiaries providing resources, such as labour/land in return for other material incentives. They do not have a stake in continuing activities once the incentives end. 5. Functional participation occurs when locals form groups usually initiated by and dependent on external facilitators to participate in project implementation. The groups may become self-dependent and are usually formed after major decisions have been made, rather than during the early stages of the project. 6. Interactive participation describes the type of participation where locals participate in joint analysis leading to the formulation of project plans and the Page 7 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 formation of new local institutions or strengthening existing ones. The groups take control over local decisions and in maintaining structures or practices. 7. Self-mobilization describes the type of participation where locals participate by taking initiative independent of external institutions and develop contacts with external institutions for resources and technical advice, but retain control over how resources are used (Pretty and Vodouche, 1997). Shaeffer (1994) also divides levels of participation into two parts: passive involvement and active participation. Passive involvement includes the mere use of a service; the contribution or extraction of money, materials and labour; attendance which implies passive acceptance of decisions made by others; and consultation on a particular issue. Active participation can be demonstrated in the delivery of a service, often as a partner with other actors; as implementers of delegated powers; and in real decision making at every stage including identification of problems, the study of feasibility, planning, implementation and evaluation. The global recognition of the need to assess the extent of community participation in development projects and programmes is encouraged as there is still a gap between participation rhetoric in politics and participation as practiced at the operational level (Oakley, 1991; Rudqvist and Woodford-Berger, 1996). There is a growing realisation that if participation, in one form or another, is an objective of poverty reduction or environmental protection programmes, its intensity must be assessed (Oakley, 1991; Bhatnagara and Williams, 1992; Clayton, Oakley and Pratt, 1997 and DFID, 1995). In undertaking a project, three main areas of participation need to be assessed. 1. The extent and quality of participation. It is important to evaluate the extent and quality of participation and where it falls on the continuum of participation (Oakley and Marsden, 1984; Uphoff, 1989). 2. The costs and benefits of participation to the different stakeholders. There is the need to evaluate the costs and benefits of participation to the different stakeholders (Oakley, 1988) as donor agencies mostly take into consideration the cost of promoting participation in development. 3. Performance and sustainability involving the development of quantitative and qualitative techniques for assessing the costs, benefits, and long-term effects of projects (Rudqvist, 1992). 5. Indicators of Community Participation Several indicators for measuring the extent of participation have been proposed. The identification of the critical traits of the process and use as broad indicators have been suggested: the vital signs of participation serving as a framework for evaluating participation; proposal of the use of the “where”, “what” and “how” of participation to be the basis for assessing participation; and finally the development of a broad continuum Page 8 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 of participation from wider to narrow and the two ends of the continuum seen as two extreme indicators have been suggested (Hamilton, 1978; Lassen, 1980; Charlick; 1984 and Rifklin and Oakley, 1996) . Other development authors and agencies have devised measures that can be used in developing indicators of the extent and quality of participation. Oakley (1991) and Department For International Development (DFID) (1995) outlined some quantifiable indicators of participation which assess the economic benefits of the project and who is participating in the project benefit. With regards to the qualitative indicators, Narayan (1995) notes that the emerging sense of collective will, involvement in discussion and decision, development of beneficiary capacity and understanding of policies and programmes are very useful indicators. The mechanisms to be used in order to promote participation such as the translation of project documents into local languages to inform people; sensitization workshops for stakeholders to elicit opinion and joint-project committees in which beneficiaries are represented are all important issues to be addressed in any evaluation. It is generally assumed that participation of rural people in the different stages of a project cycle will either be beneficial or a cost in the long run depending on how the beneficiaries are involved in the project. 6. Participation in EIA in Ghana In a review of EIA reports produced in Ghana, Sampong (2004), (cited in ECA (2005), ranked the Environmental Impact Statements (EIA) as satisfactory perhaps because the country had considerable experience with the process, dating back to Act 490 of 1990. However, most of the Environmental Impact Statements (EISs) were graded very low due to the weaknesses in and lack of necessary skills, information and data on several factors. One of these factors was public participation, even though it was acknowledged that some progress appeared to have been made since 2001. Akabzaa and Darimani (2001) noted various challenges with the public participation in the EIA process is Ghana. These include: (i) (ii) (iii) the sources of information, which are the national press or the premises of District Assemblies, are inaccessible for these communities. The technical language of the EIA, which is impossible for the people in a community to read and understand. the confidentiality clause for Environmental Audit Reports, which allows the mines and EPA to treat the Environmental Audit Reports as confidential documents and therefore unavailable to the public. Page 9 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 (iv) (v) (vi) (vii) (viii) The proviso in the guidelines on mining, which a company‟s obligation to accept recommendations made by an audit report, thus reducing the EIA to a mere submission of a report. the fact that, the proponent or their consultant conducts the study and therefore establishes the desirable content of the report after consultation with selected individuals the fact that public hearings are nothing more than public relations forums where companies largely dwell on the expected positive economic benefits of the project to both the state and the local population while downplaying the negative impacts of the project. the lack of follow up in Ghana where hearings have raised serious objections to an EIA. the failure of EIAs to adequately deal with the social impact of mining projects. The social issues dealt with are usually issues of payments of compensation and royalties. 7. Methodology The study employed a descriptive design in an attempt to describe the reality of a situation as compared with what the law states. The study area consists of three large scale mines and their catchment areas, Newmont Gold Ghana Limited in the Birim North District of the Eastern Region; the Goldfields Ghana Gold limited‟s mine in Prestea-Huni Valley District and Adamus Resources Limited‟s new mine in Ellembelle District, both in the Western Region of Ghana. Both purposive and convenience sampling methods were adopted to select required respondents for the study. Two categories of respondents were sampled. The first category was made up of respondents from communities affected by the activities of the selected mining companies. These included some selected chiefs, queen mothers, community leaders and youth. The communities and key informants within them were selected purposively and then youth members were selected conveniently to become respondents. The second category of respondents consisted officials of the mining companies, regulators of mining and district planning authorities within whose jurisdiction these mining activities resided. Purposive sampling methods were used to sample key informants from various institutions for the study. Table 1 presents a distribution of respondents and their locations. Page 10 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 Table 1: Distribution of respondents and their locations Respondent Locations Data collection Number tool EPA -Accra Interviews 1 -Koforidua 1 -Takoradi 1 -Tarkwa 1 MINCOM -Accra Interviews 1 -Takoradi 1 -Oda 1 -Newmont Gold GL -Accra Interview 1 1 Chiefs -Damang Interview 1 -New Kyekyewere 1 -Teleko-Bokazo 1 -Koduakrom 1 Queen mother Salman Interview 1 District Planning -Birim North Interviews 1 Officers -Ellembelle 1 -Tarkwa Total Source: Fieldwork, 2010 16 Two communities were purposively selected in each of the catchment areas of the three selected mining companies and three Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) conducted for adults, youth males and youth females in each of these communities. Table 2 gives a distribution of the FGDs done. Table 2: Distribution of FGDs organised District Community Number of FGDs Prestea-Huni Valley Huni Valley 3 Kyekyewere 3 Ellembelle Salman Teleko-Bokazo 3 3 Birim North Hwakwae Yayaso 3 3 Total Source: Fieldwork, 2010 18 Page 11 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 8. Participation in Environmental Impact Assessment The involvement of key stakeholders at all levels of activities is desire-able for a sustainable implementation of any project or programme. This study investigated the involvement of various stakeholders. Most respondents felt that everybody that needed to be involved took part in the various stages of the permit acquisition process. A minority of the respondents said they sometimes saw people around, doing one activity or the other and sometimes taking part in meetings, but they were not clear who the people were and what titles they held. The study identified three main stakeholders in this process; these include: the mining companies and consultants working on their behalf; government regulation agencies and communities themselves (who were sometimes represented by NGOs/CBOs). The main regulating institution respondents identified was the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Other entities of government identified were the Minerals Commission, Forestry Commission, Water Resources Commission, Ministry of Local Government and Factories Inspectorate and Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice. Organisation of public engagements Most of the public engagements were organised in public meeting places. Public announcements were made on FM stations or pasted on information vans; letters were also sent through elders who had attended earlier meetings; or sometimes the traditional gong-gong was beaten and the information about the organisation of the meeting was disseminated. These meetings were usually organised in order to avoid market or farm days so that more people could attend. When meetings were held between the youth and the company or between chiefs and the company they were held on the premises of the company. Most members of the communities who were not part of these meetings were suspicious that the community members attending the meetings were influenced by the company, which gave them treats and or gifts so that they granted concessions to the company to the detriment of the whole community. In some instances the meetings were held between community leaders like the chief, Assembly man or Member of Parliament and the mining companies or their agents mostly in the presence of the District Chief Executive or a member of the District Assembly. The leaders then organized the communities to inform them of the meeting deliberations. The respondents were almost unanimous on the fact that it was the mining companies that organised these public consultations, which were generally chaired by chiefs, Assembly men or other community leaders. However, in Teleko-Bokazo one respondent noted that the EPA had organised public Page 12 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 forums there. In Yayaso, the male youth noted that they had heard of some public fora organised by the EPA and in one instance, the Forestry Commission had organised one. This may possibly be because the mining pit would affect the Ajenjua Forest Reserve, a concern which had generated public discussions led by NGOs, focusing on the negative environmental impacts. Since the reserve is managed by the Forestry Commission, they then might have had to organise a public forum to gather community opinions. Barriers The major barrier to effective public participation in the EIA was related with the reconciliation of the technical nature of the mining processes and the low capacity of affected communities to understand. Even though the EPA makes available to the concession district a copy of the Environmental Impact Statement, the capacity of the general public to understand the content was seen as usually so low that in essence the process of public participation was not as effective. This is because the people the EIA sought to protect could not appreciate it. It was also noted that because of the technicalities of mining, sometimes the Environmental Impact Assessment did not achieve its desired effect. The reason is that the public for whose benefit it was done could not comprehend it. Additionally, mostly the Environmental Protection Agency had no offices in the districts to explain the technicalities to interested community people. Another barrier mentioned was that not all the affected people got the chance to participate in the EIA because of the way the public fora were organised. Specifically the communities were represented by selected people and also the public fora were not held in all the communities affected by the project, but in selected ones. The arduous nature of public participation processes lead to prolonging the time used to take decisions on mining. This was one of the barriers to effective participation in the EIA noted by respondents. The personal interest of people at various levels of the permitting process was also noted to be a barrier to effectiveness as these people might inhibit both the flow of information and the imposition of sanctions, thus flouting the EIA law. The law in itself was seen as good, but the personnel implementing it might sometimes either bend the rules, stifle information flow or could not implement them without fear or favour. The fact that mining in the Ajenjua forest reserve was permitted, was seen as a specific example of ineffectiveness of the EPA in implementing the law without fear or favour. The EPA was encouraged to set up more well manned and stocked district offices for proper monitoring especially in mining areas. Page 13 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 9. Meetings and their organisation Leader of meeting The leadership of most meetings is very important for steering the meetings to a successful end and in determining which discussions would be recorded for further attention. The community respondents noted that most of the time, either the company‟s or the EPA‟s officials chaired the meetings. Sometimes, they were chaired by the Corporate Affairs Manager or the Community Affairs Manager or any other representative of the company or agency. Respondents believed that this was a problem because only issues that favoured the company were mostly discussed at the meetings. At other times, during public meetings between the company and the community, either the chief or the Assembly man or any other opinion leader in the community was elected to chair the meeting. At these meetings, issues affecting the communities were given more space for discussions as the leadership was from the community. The leadership of the meetings generally handled their responsibilities well. This is because even though the people had no idea of EIA, they were able to convince them to come to agreements at the end of these deliberations. However, respondents were divided on the neutrality of the leadership. Most respondents believed that they influenced the decisions made at the meetings. The respondents explained that people were convinced to accept resettlement packages proposed by the company even though they were not satisfied with them. Some of the comments captured at FGDs in some of the communities regarding the leadership of meeting influencing negatively, issues agreed on at the meetings are presented for illustration: One participant in the female youth FGD in Hwakwae noted; “What happens is we do not know whether our views are presented to the big bosses or not. This is because after the various engagements they do not come back to tell us whether our concerns would be met or not. So we can‟t tell whether they influence it or not, but once we do not hear from them, we can conclude that they do not like our decisions”. A young male in the FGD in Teleko-Bokazo also noted; “None of the decisions have seen the light of day. With this in mind, we can say that they definitely influence negatively decisions taken. The fact of the matter is we have not been able to take major decisions because what the company says is always different from what we also say”. A female respondent in Yayaso also said; Page 14 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 “It was Newmont that facilitated the meeting, so of course they would negatively influence the decisions. The decision to implement what is decided on largely rests on the mining company. The reason we say they negatively influence the decisions is that none of the decisions taken have been implemented. If nothing has happened with the decisions, then everybody can conclude that the decisions are swept under the carpet”. A male respondent in Salman said; “Since they are best serving the interest of the mining companies, relevant issues bothering the community are carefully eliminated”. The quotations from the various areas show that the situation where people did not trust that decisions made at meetings cannot be a random occurrence and that, the respondents who felt the leadership of meetings negatively influenced decisions were passionate about this allegation. Presence of influential people at public meetings The attendance at public meetings by influential people, like managers, directors, etc who took decisions on what the company did and other regulatory agencies helped the meetings to draw workable plans of action that were more likely to reflect consensual position. The presence of these people at these meetings was determined from the respondents. Most community respondents thought influential people attended the meetings but they did not know for sure. The community members were not sure of the roles these people played. Another group of respondents were categorical that the influential people were usually not present at the public fora organised. A member of the adult focus group discussion in Hwakwae substantiated this position thus: “For our part, all the opinion leaders are present. At such forums, we do not know who is supposed to be present from either government or the company. We know the top brass of the company are also to be present. The question is we do not know whether the right person is represented. This is because sometimes, at such meetings when you ask them a question, those from the company who are present will say that, they will have to refer the question to their bosses for an answer. We think it will be appropriate that those people in the company who will be in the best position to answer our questions are present”. In these situations, it became impossible to achieve consensus as the decision makers Page 15 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 were not present and issues coming out of the meetings would have to be relayed to decision makers who would then take the final decisions. This is also one of the reasons why the community respondents complained that these public fora were public relations gimmicks. Issues discussed at meetings Respondents mostly said that issues of resettlement of both households and livelihoods and compensations for farms and farmlands lost were discussed at the meetings. These discussions centred on who had to be resettled, whether the resettlement should be in terms of new apartments being built for the affected people or whether they had to be given monetary compensation. Those who opted to be given new apartments then went into negotiations on what kind of building, the number of rooms etc. While those who had to be paid compensation packages also then went into those negotiations. In Salman, for instance, respondents said that the mining company informed the community that households who lived in mud houses were going to have their houses paid for but those living in cement block buildings were going to be resettled on the new resettlement site. In the Teleko-Bokazo and Yayaso areas, the discussions centred more on the mining project, the impacts and their mitigation measures. „Discussions were around the project, its advantages and less on the impacts‟, a resident of Teleko-Bokazo said. Youth in Yayaso also said that the company talked more about the advantages of the mining and less about its disadvantages. Another issue discussed at the meetings were how sources of drinking water for instance were going to be affected by the mining activities. The perceived developments the mining was going to bring to the areas were also discussed at the public fora like improvement in infrastructure and job creation. Other respondents, for example, women in Huni Valley said that the company talked about many more other issues they did not understand, which were technical in nature and also conditions that had to do with the permit the company had acquired. At these gatherings, the company informed the members on the issues and people were allowed to ask questions and answers were given. Some of the respondents were not pleased with the answers sometimes given, as they did not see them as meaningful answers. The female youth respondents in Yayaso summed up their views of the public consultations thus: „The various public fora were just cosmetic shows to the authorities that they Page 16 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 were following due process. It was a talk shop where after, nothing happens. We were not properly consulted and adequately involved in the process. They promised us many goodies but they were all lip service. Even though we have not been compensated, the company has started destroying our farm which is our only source of livelihood which we think is against the laid down rules. This may lead to unhealthy clashes‟. Understanding of the issues discussed Two main topics emerged regarding how well the respondents understood the issues discussed at the meetings. The first had to do with the issues of compensations and resettlement of the people, which the local community respondents generally understood. But when it came to the conditions of resettlement or amount of compensation, the respondents did not comprehend why they had to be given packages they thought were inadequate for the losses they were incurring. The second arena of the discussion had to do with the mining project itself and the technical as well as the scientific information given. The local community respondents did not understand the information because it was too technical and also because efforts to interpret for the local people was inadequate. Given their inability to understand, respondents paid little attention to this aspect of the meetings. A male youth respondent from Hwakwae had this to say about the issue of communication between the local people and the mining company: „I remember when the issue of moratorium came, I asked some farmers whether they understand it and they said no but have heard it before at their various meetings with the company. When I explained it to them they were shocked and angry that the company did not explain it well to them. So there are times people, especially farmers face such difficulty. Sometimes we understand, sometimes we don‟t understand. When the moratorium issue came, some understood it as “stop work”. When we asked them they told us it is not true but after it was declared we realized that what we knew about the moratorium meaning “stop work” was true because they are preventing us from farming.‟ Respondents said that though people were not prevented from speaking at the fora, majority of people had no opportunity to ask a question because the organisers of the meetings limited the number of people allowed to speak and this number was generally less than the number of attendees. Some female adult respondents in Huni Valley and Kyekewere felt that the women in particular, were not given enough chance to speak, as in most instances, only the leaders of the community delegations were allowed to speak. These leaders were predominantly males. In order for communication to proceed and result in desired outcomes, public Page 17 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 discussions should close when all groups have an understanding of the issues for discussion and are aware of the salient points of the discussion. The meeting participants normally asked for clarifications on the points that were not clear and most said the presenters normally explained the same points again. These explanations generally did not result in better understanding by the people. Sometimes, like in a case of Darmang, the company hired consultants to organise further meetings to explain issues in the local languages to the people. The companies were alleged to claim this was the normal protocol. Some respondents contended that the company normally came to the communities after they had taken decisions and the objections and calls for further clarifications did not result in much change in the original plans of the companies, leaving the local people with no possibility of influencing decision making. For instance in Teleko-Bokazo, the community told the company that they did not understand so the company representatives stated they had to reorganise and return to offer better explanation: but the company never went back. Sometimes, like in the case of Salman, the meeting ended abruptly or the meeting was adjourned for over a year and then processes of consensus building were engaged in to get to an agreement. This also occurred in Huni Valley. 10. Influence of participation on understanding of technical issues Clarity of terms In the meetings and public forums, the respondents noted that the experts from the regulators or the companies tried to thoroughly explain the various terms, technologies and science to help the community understand. Most of the community relations officers of the mining companies spoke the local languages and they tried to translate these discussions for the community. Even when other experts could not speak the local language, translators were recruited to do the translations. There were, however, difficulties posed by this situation as there were limits to how well one could explain scientific or technological jargons and concepts to people who often times were illiterate. Knowledge used The kind of knowledge used to arrive at decisions for project implementation often determines what outcomes the project achieves. Both intuitive local knowledge and anecdotal evidence were considered by the Minerals Commission in arriving at these decisions. For instance, in the Abirem area the community people indicated that the Ajenua Bepo forest had some sacred spots. Those spots, according to the District Assembly, were going to be preserved in the mining project. Page 18 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 The mining company had this to say about the sources of information used to arrive at decisions: “We listen to every piece of information because in the end it helps us prepare better for the project. So for a particular community we may be told that a river gets dried up when their goddess is angry for some reason. Ours would be to observe those times and so find out the reasons if we intend to use the river and we may find out that there is a perfectly good reason why this happens maybe because it is seasonal. We then prepare using the knowledge that for a particular period the river may not be useful to us. We do not take into consideration everything that is said by the people but we do our best to respect the culture and belief of the people in order to ensure a smooth working experience with them”. In gathering this information, the companies and regulators used different sources and methods. The methods used were very much dependent on the kind of community that was affected and whose participation was sought. The regulators noted that they tried to be as down to earth as possible in order to elicit the correct information from the community. In doing so the project, its prospects, effects and impact could be clearly explained to the community to ensure their understanding of the project, which was needed for them to make an informed decision. One of the mining companies said they did not go into the communities just to elicit information, but also to inform them about their intentions and its likely impacts through durbars; films and even field trips to other mines so that the community saw first hand, what they were about. So for example Newmont took a community to Obotan Gold mines, which was closed but had been reclaimed so the people understood that their land after mining was not going to be left with big gaping holes which were death traps. The company collected information by constituting different groups including farmers, market women and even children. For example, they set aside a particular time for taxi drivers by contacting, where available, their respective unions since the project was likely to occasion fleet increase. Even before they went to the EPA, they had solicited the views of the groupings within the community to find out the best practices to be followed. They sometimes spent a whole day with each of these groupings to be able to do thorough work. The company also noted however that because they did a lot of underground studies and visits they got to have a pretty good idea of every possible issue that arose as a result of their project and these were things they took steps to deal with even before they were asked to do an EIA. During their consultations with the various groupings within a community they also took the trouble to provide for dispute settlement processes using the representatives of the people so that by the time they were done consulting them they already had solved a lot of the problems that might have been occasioned by the intended project. Page 19 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 Understanding of technical issues by communities One important aspect of participation of local people in the project cycle is the transfer of knowledge from the experts to the local people. Enquiries into whether the type of meeting participation translated into a better appreciation of technical issues by the local community respondents show that majority of respondents did not experience improvement in their level of appreciation of technical issues. However, some other respondents had an improvement in technical appreciation. A chief interviewed in Teleko-Bokazo intimated that he had become aware of how dams were going to be built to contain cyanide waste. Respondents who said there was no change in their technical capacity due to their involvement with the projects were asked to suggest ways to make sure this happened in future projects. The most frequent response was that the mining companies should ensure that translations of the technical issues were communicated to them before the meetings were conducted so that they could understand and make either productive contributions or criticisms. This suggestion has already been made part of the permitting process, but the translation into local languages were not addressed in the law. Section 15(1)(d) of LI 1652 states: Where an applicant has been asked to submit an environmental impact statement it shall be the responsibility of the applicant to (a) advertise in at least one national newspaper and a newspaper, of any circulating in the locality where the proposed undertaking is to be situated; and make available for inspection by the general public in the locality of the proposed undertaking, copies of the scoping report. If this provision is enforced and adhered to, then it would be possible for community people who are literate to read these reports before the public fora and therefore make meaningful contributions. Male youth in Hwakwae summarised thus: „Newmont should employ people to explain the technical words to us anytime we meet. When they say something and you do not understand and you ask for clarification they will tell you that they will have to refer it to their big boss, but nothing happens in such instance. We will also plead with government to impress on them to make all their work easy for us to understand so that later we will not be fools in the future‟. One other suggestion for improving the technical capacity of the community was that they should be taken to view the site. The last suggestion made was that the communities should be supported to engage the services of a consultant or consultants Page 20 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 to attend meetings and fora so that they could help to explain trends in discussions and to negotiate properly on their behalf. These consultants should be recognised and allowed to sit in meetings and discussions as part of the EIA and all conditions for permitting that border on the community livelihood. 11. Role in meetings The roles played by different stakeholders are as discussed in this sub section. The chiefs usually played the role of representatives of their communities in most of the meetings they attended. The District Assemblies were not aware of any specific provision in the EIA law that mandated them to play a specific role in the process. However, they usually attended these meetings as interested stakeholders. Sometimes, the Metropolitan, Municipal or District Chief Executives were chosen to chair the functions. The Assemblies usually answered any questions related to how the Assembly would ensure security in the area. The Assembly was also consulted for data on the area and also to facilitate the assessment process by informing the general populace about the mining operation and the organisation of various processes of the operations. Once the EPA and Minerals Commission had permitted the mining, the Assembly issued or refused to issue permits for their physical installations like buildings and claim property rates on them. The Assemblies were to ensure that no installation of the companies violated any physical development plans of the District. The community respondents believed that their role in these meetings was just to listen to the information given by the company officials and to ask questions when they did not understand anything. Thus, the community really did not play any role in the meetings. This situation does not bode well for enhanced participation of them in the EIA. The communities just engaged in this process as passive participants (Pretty and Vodouche, 1997). 12. Perception and practice of public participation This section reports on how the concept of public participation was understood by the regulating agencies and the mining company. The agencies of interest were the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies (MMDAs), Minerals Commission, EPA and the mining company. This analysis was done with a view to establish the knowledge basis informing how participation was operationalised on the field regarding the permitting process of mining and the mining process itself. The second part of the section then looks at issues related with the actual practice of participation in the EIA stage from the perspectives of the governmental and business entities. Perception of public participation Page 21 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 The perceptions of public participation held by the various regulatory and business entities sampled for the study are discussed in this sub section. One respondent from the EPA saw participation as an action that allows a person affected by a project to be involved from the beginning to the end. The concept of public participation denotes the process of eliciting the views, concerns and interests of the public so that any final decision that was taken on an issue or project reflected the opinion of the public. Another EPA respondent perceived participation as a level above consultation, where affected people were told the details of the project at each level. Another perception of participation from the EPA was informing communities about the project and as far as the process of decision making was concerned, while another EPA respondent perceived that public consultation and public participation meant the same thing. With the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assembly (MMDA) planners, public participation was seen as the involvement of the citizenry in the process and procedures about company activities in which people have the chance to raise their concerns or in which the general public becomes involved in decision making processes that affect them either negatively and positively. The Minerals Commission respondents saw public participation as a matter of identifying who will be involved or affected and allowing them to have a say in a particular project; the processes involved, when it would start and their concerns addressed before the start of the project. The mining company respondent believed public participation to essentially be the involvement of the public in decision making. This might take the form of getting to know their views, concerns, etc., in relation to the intended project and soliciting their assistance to ensure that the project was wholesome. The practice of public participation by regulators and business The practices of participation by various regulators were explained from both the institutional and public respondents. The Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies (MMDA) planners reported that a public forum was held where the interested parties could interact, questions were asked and answers given. Another planner saw the public participation practice as a public hearing where all stakeholders were invited and questions asked for answers to be given. The last reported practice as seen by another MMDA planner was a situation where representatives of affected communities were presented with community score cards to do an assessment of the project. The Minerals Commission saw the practice of public participation as depending on the type of the project and its impact on communities or the environment; a public hearing Page 22 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 might be done as part of public participation. Essentially however, public participation could also be done at all stages and at all levels of a projects‟ lifespan. What happened usually was that before, during or after the review, i.e. after an Environmental Impact Statement was submitted by the proponent to the EPA, it was reviewed by a committee to determine if the document reflected the thinking of the community. Before a public hearing, the EPA went around the community to inform them about the need for it; this is called a recognisance visit. After the approval of the Environmental Permit if there was the need for a review of the terms, for example a change in work plan or operations which would have environmental consequences, then a public hearing was organised and the public involved. The mining company initially held consultations with various groupings within the community and informed them of the project. Issues about the project that the company shared with the community includes the activities of the project; impacts of the project on the communities; impacts of the project on the accessibility to natural resources by the community etc. The groups normally consisted of people perceived to be directly influenced by the operations of the mines, namely farmers groups, youth groups and trades groups like hunters. These consultations occurred before the application of a mining permit. Participant views and concerns were collated to be presented at public hearings to further sensitise the community and assure them of the company‟s intentions. During the public hearings the company also ensured that as many people and groups as possible had the opportunity to express themselves and that the company would respond in clear and simple language that most people could understand. Drivers of the public participation process The Minerals Commision (MINCOM) saw the major drivers of the public participation process as non-state actors; NGO‟s like WACAM, Coalition on Mining etc. and particularly WACAM, which participated in most of the public hearings and even went to the communities to teach them about the project and to mentor them on how to ask relevant questions. The mining company also noted the importance of NGOs in this domain. NGOs took the lead and drew attention to many activities that might have been taken for granted. For example NGO‟s were reported to have highlighted the fact that usually in these assessments, the universities were usually interested in studies, but there should have been baseline studies that could reveal the impact of the project over a longer period instead of just ending at the periphery. There was no interface between the community, the mining company and the relevant agencies in this regard so in the long run the community was still at a loss. Benefits Page 23 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 Public participation allowed for the communities to express their concerns, highlight omissions of vital information and to correct of errors made in the EIA process. The participation of the public usually brought out very salient factors like areas held by the communities as sacred, which needed to be considered by the project proponents. One of the benefits of participation as perceived by the mining company was that it was an on-going educational process which also created a sense of belonging in the community promoting the willingness of the communities to support and cooperate with decisions. The issue for discussion here is that it appeared to all the regulators and company that participation would only benefit the communities. What then happened was that these agencies saw themselves as doing communities a favour by engaging them in the rudimentary participation of information dissemination. The first point that must be made is that the law on EIA in Ghana requires participation to be part of the process. A benefit derived from this is that by engaging the public, the companies avoid being sanctioned. When seen this way, agencies‟ attitudes towards the participation of communities in the EIA could definitely be perceived by the community people more positively. 13. Effectiveness of the public participation process The MINCOM respondents assessed the process as very effective because EPA went to every community on the property and the people were invited to express their views. The company felt public participation in EIA was generally effective but could definitely be better. A typical example was the fact that the Environmental Assessment Regulations, LI 1652 in its various processes like scoping and posting of notices, contains elements of public participation. Surprisingly these comments, the company noted, were mostly taken seriously by project proponents because it was to their advantage to understand the perspectives of the people who were impacted by their activities. For the mining company, the EIA process was one of the best in Africa; so good that, it was added, only a few lapses like operational lapses regarding the issuance of notices and monitoring of information flow needed to be addressed to make it a near perfect one. The company further noted that, even though there were many players like the EPA, Minerals Commission etc and all the relevant institutions were fairly represented in most of the environmental impact procedures, more often than not the EPA predominated. For the mining company, EPA was concerned with the more ambient side of things but there were other impacts of a project that other institutions were better qualified to deal with. For example, for mine design pits and the project level design they believed the Inspectorate Division of the Minerals commission was better suited to deal with it. They therefore believed that institutions that were better at doing specific things should be allowed to regulate those specific sub sectors. However, they were optimistic that Ghana had a legal framework for the EIA that was considered to be good. Since the Page 24 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 mining sector was very organic, the continued growth and learning would finally result in a good system where all these concerns and challenges would be adequately addressed. 14. Suggestions for improvement of participation With regards to respondents suggesting ways of improving participation of affected people in the EIA process, the District Assemblies thought that the coverage of participation should be widened to allow for diversity of views that could be achieved by expanding the number of representative stakeholders beyond communities to be affected to families to be affected. Also, if the operation will affect eight communities, public hearings and any other meetings should be organised in all eight and not communities chosen because of population or size. The Minerals Commission suggested that even before these community hearings, someone from the community or someone who understood the language of the community should be recruited to break things down to the communities before the need for a public hearing even arises. “They should not be consulted only as a cosmetic measure”, one respondent remarked. Another suggestion from the Minerals Commission as well as the mining company was that much more education was necessary to ensure that the community felt a part of the EIA process. In some instances, communities have existed for centuries and their survival often has depended on the resources they extracted from the lands and forests. They naturally owned the lands and forests and have inherited this ownership from their ancestors. The permit process, which sometimes took less than a year to complete, was too short a time to allow the communities to fully accept that their access rights to these resources might have to be curtailed to make way for the mines. It was therefore suggested that government should expand access to schools in all areas so that the people already had an understanding of the issues at hand before an outsider came in to convince them to allow mining. 15. Conclusion The study concludes that even though there were generally several different levels of meetings, the participation of communities was mostly limited to information dissemination and to a smaller extent consultation. These constituted the least three of the seven levels of participation defined by Pretty and Vodouche, (1997). Given the nature of the meetings, final decisions on the projects were usually done with minimal influence of the perspectives and situations of the local communities. Processes where communities are involved in the process of mining right from the decision to prospect through the mining phase would ensure proper more active participation. The major problem inhibiting community participation in the EIA was a combination of illiteracy in most mining areas coupled with the non-transparent manner in which most Page 25 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 of the documents and information that informed decision making processes were created. When public fora shared technical documents, they were not made available to the communities for studies beforehand. They were translated for representatives of communities to ask questions on behalf of their people. This process did not allow for more participation of the communities and resulted generally in a situation where public fora were organized to satisfy the EIA permitting conditions but not to actually bring the communities on board so that decisions would benefit both the proponent and the communities. This study recommends that the Government of Ghana through the EPA should ensure that the EIA process is more transparent than it is now. This can be achieved by for instance, ensuring that technical documents used as a basis for the organization of community meetings and fora are made available to the communities for periods adequate to allow for proper studies before the meetings and fora are organized. It was suggested that at least 90 days should be given for this purpose. In addition, government through any appropriate agency and in consultation with affected communities should hire the services of consultants to act for and on behalf of the affected communities in negotiating appropriate redress for the environmental impact of mining projects in Ghana. References Akabzaa, T. and Darimani, A. 2001. Impact of mining sector investment in Ghana: A study of the Tarkwa mining region, SAPRI, Accra. Aubynn, A. K., (1997). Land-based resource alienation and local responses under structural adjustment: Reflections from Western Ghana. Institute of Development Studies, Helsinki. Bhatnagar, B. and Williams, A. C. 1992. Participatory development and the World Bank: Potential Direction for Change, World Bank Discussion Paper Series 183, World Bank, Washington D. C. Boocock, C. N. (2002). Environmental impacts of foreign direct investment in the mining sector in sub-Saharan Africa. www.natural-resources.org/minerals/docs/oecd, accessed on 15/05/07. Boon, E. K. and Ababio, F. (2009). Corporate Social Responsibility in Ghana: Lessons from the mining sector. 29th Annual Conference of the International Association for Impact Assessment, 16-22 May 2009, Accra International Conference Center, Accra. Charlick, R. B. (1984). Animation rurale revisited. Longmans, London. Clayton, A., Oakley P. and Pratt, B. (1997). Empowering people: A guide to participation, UNDP, New York. Page 26 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 Cohen, J. M. and Uphoff, N. T. (1980). Participation‟s place in rural development: Seeking clarity through specificity, World Development Journal Vol. 1(8) pp 324-329. Cohen, J. M. and Uphoff, N. T. (1977). Rural development participation: Concepts and measures for project design, implementation and evaluation, Cornel, New York. University. Department for International Development (DFID) (1995). Guidance note on indicators for measuring and assessing primary stakeholder participation. DFID, London. ECA (2005). Review of the application of Environmental Impact Assessment in selected African countries, Economic Commission for Africa, Addis Ababa. Ghana Chamber of Mines (2009). Performance of the mining industry, 2009, Ghana Chamber of Mines, Accra. Hamilton, D. (1978). Beyond the numbers game, McCatchan, California. Institute of Development Studies (IDS) (1998). Participatory monitoring and evaluation: Learning from change. IDS Policy Briefing Paper Issue Vol. 12. Institute of Development Studies, Brighton. Inter-American Development Bank (1998). Supporting reform in the delivery of social services: A strategy. Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, D. C. Kahssay, H. M. and Oakley, P. (1999). Community involvement in health development: A review of the concept and practice, World Health Organization, Geneva. Karl, M. (2002). Monitoring and evaluating stakeholder participation in agriculture and rural development project: A literature review, World Bank, Washington, D. C. Khwaja, A. (2001). Can good projects succeed in bad communities? Collective action in the Himalayas. World Bank, Washington, D.C. Lassen, C. A. (1980). Reaching the assetless rural poor, India Social Institute Press, New Delhi. Mabogunje, A.L. (1980). The development process: A spatial perspective, 2nd Ed., Unwin Harman Ltd, London. McGee, R. J. and Norton, A. (2000). Participation in poverty reduction strategies: A synthesis of experience with participatory approaches to policy design, implementation and monitoring, Institute of Development Studies, Brighton. Narayan, D. (1995). The contribution of people‟s participation: Evidence from 121 rural water supply projects, World Bank, Washington, D. C. Nelson, N. and Wright, S. (1995). Power and participatory development: Theory and practice, Intermediate Technology Publications, London. Oakley, P (1988). The monitoring and evaluation of participation in rural development, FAO, Rome. Oakley, P (1991). Projects with people: The practice of participation in development. International Labour Organization, Geneva. Oakley, P and Marsden, D. (1984) Approaches to participation in development. Geneva: International Labour Organization. Page 27 Proceedings of 23rd International Business Research Conference 18 - 20 November, 2013, Marriott Hotel, Melbourne, Australia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-36-8 Ofori, S.C. (1991). Environmental Impact Assessment in Ghana: Current administration and procedures -Towards appropriation methodology. Environmentalist 11(1):45-54. Paul, S. (1987). Community participation in development projects. Washington, D.C.: World Bank. Pretty, J. N. and Vodouche, S. D. (1997) Using Rapid or Participatory Rural Appraisal, in Swanson (ed), Improving agriculture extension: A reference manual. Rome: F. A.O. pp 47-55. Rifklin, S. and Oakley, P. (1996). Paradigm lost: Towards a new understanding of participation in health care programmes. Geneva: WHO. Rudqvist, A. (1992). The Swedish International Development Authority: Experience with popular participation, in Bhatnagar and William (eds), Participatory development and the World Bank: Potential directions for change. Washington, D.C. : World Bank, pp 58-66. Rudqvist, A. and Woodford-Berger, P. (1996). Evaluation and participation: Some Lessons. Department for Evaluation and Internal Audit, DAC Expert Group on Aid Evaluation, SIDA, Stockholm. Shaeffer, S. (Ed) (1994). Partnerships and participation in basic education: A series of training modules and case study abstracts for educational planners and managers. Paris: UNESCO. Uphoff, N.T. (1992). Fitting projects to people, in Cernea, M. (ed), Putting people first: Sociological variables in rural development. New York : Oxford University Press, pp 235-294. Uphoff, N.T. (1989) Participatory self-evaluation of P.P.P. group and inter-group association performance: A field methodology. FAO: Rome. WCED, (1992). Rio declaration on environment and development. World Conference on Environment and Development, United Nations, New York. World Bank, (1999). Environmental assessment sourcebook. Washington, D.C.: World Bank. World Bank, (1991). Local participation in environmental assessment of projects. Environmental Assessment Working Paper 2. Environment Division, Africa Region, Washington, D.C.: World Bank. Page 28