Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

16 - 17 December 2013, Hotel Mariiott Casamagna, Cancun, Mexico, ISBN: 978-1-922069-38-2

Private Equity Acquisitions and the Competitiveness of

Buyout Firms

Kerstin Peschel, Anup Nandialath, Ramesh Mohan and Stephanie

Lizardi

Keywords: Private equity, competitiveness, buyout firms, agency costs

Private equity is an important source of financing for French companies. This paper examines the relationship between private equity and the competitiveness of buyout firms in a

French context. Prior literature has assessed private equity markets and emphasized mechanisms including the replacement or reorganization of management, the reduction of agency costs, the financial pressure through leverage, the influence of shareholders, and the management expertise of the fund.

However, as the majority of these existing studies focus on private equity in the U.S. and U.K., little consensus has been achieved about the application of these results to France. In this paper, we discuss the mechanisms of private equity in a French context. We analyze the criteria on which buyout companies are chosen by funds, as well as the relationship between private equity and subsequent firm performance. Our findings show that

French private equity funds select companies that, in comparison to their competitors, are larger in size and are better performers.

Our results also show that following a buyout, companies do not experience a significant performance improvement. Based on our empirical analysis, we find no significant evidence that French private equity creates long-term value.

1.0 Introduction

In the most recent decade, private equity has become an increasingly important source of financing for French companies. Particularly in the context of the recent financial crisis and increase in bankruptcies, the relationship between private equity and subsequent firm performance has reemerged as a topic of interest. The number of private equity firms and buyouts in France have increased significantly in recent years, with the total volume of buyouts rising from 821 million EUR or 0.2% of

GDP in 1998 to 7.4 billion EUR or 0.5% of GDP in 2008 (AFIC). At the same time, the skills needed for financial engineering and quantitative analysis have not kept pace. In response, funds have developed more distinctly qualitative strategies. For example, some funds use a core strategy that involves the re-organization of governance structure, while others focus on the improvement of operational efficiency (Berg and Gottschalg, 2004).

______________________________________

Kerstin Peschel, Senior Associate, Boston Consulting Group, Casablanca, Morocco,

Email: kerstin.peschel@gmail.com

Anup Nandialath, Assistant Professor, College of Business, Zayed University, Academic City Al

Ruwayyah, Dubai UAE, P.O. Box 19282, Email: anup.nandialath@zu.ac.ae

Ramesh Mohan, Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Bryant University, Smithfield RI

02917, Email: rmohan@bryant.edu

Stephanie Lizardi, Research Associate, Center for Global and Regional Economic Studies, Bryant

University, Smithfield RI 02917, Email: slizardi@bryant.edu

1

Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

16 - 17 December 2013, Hotel Mariiott Casamagna, Cancun, Mexico, ISBN: 978-1-922069-38-2

A number of existing studies have been conducted in the U.S. and U.K. to examine private equity investments. These analyses involve private equity value creation, and its impact on profitability, productivity and plant efficiency. The majority of these studies conclude that private equity has a positive effect on performance indicators, including growth in assets, EBITDA-Margin, cash-flows and total factor productivity. However, as these studies have been conducted in anglo-saxon countries such as the United States of America (USA) and the United Kingdom (UK), an inherent question is whether these effects are fungible across various geographical boundaries, for example, France which bears significant differences from anglo-saxon economies.

There are several crucial differences between the French and U.S. or U.K. private equity markets which have been described in past studies and existing research. To begin, Glachant et al. (2008) point out that French SMEs are characterized as smaller and more fragile than their foreign peers. These companies often lack comparable financial support, in terms of access to debt and equity.

Accordingly, these companies are often less innovative and dynamic. In addition,

Desbrières and Schatt (2002) show that French buyouts focus mainly on transitioning from family-owned SMEs to corporations, as opposed to creating a spin-off company from an already well-established corporation, as is often the case in the U.S. or U.K. Boucly et al. (2009) also emphasize this difference. They state,

"France is a country with many familymanaged businesses … which may sometimes lack the managerial and financial expertise needed to take advantage of all growth opportunities". Also, most U.S. and U.K. empirical approaches focus on agency costs, the impact of debt and the concentration of ownership through buyouts. These factors may be of less importance for French companies. Other variables including the impact of shareholders and the management expertise of the fund's general partners may have a larger impact on subsequent firm performance in

France.

The present study examines the models developed in the U.S. and U.K. in the context of French buyouts. This study also expands on existing French private equity research by exploring additional causal mechanisms. Specifically, this paper asks the following questions: (i) How do private equity-based companies perform compared to competitors prior to the buyout? (ii) How does their performance evolve during the investment period? (iii) What is the impact of private equity on subsequent firm competitiveness?

2.0 Literature Review

Jensen (1989) published one of the first private equity papers. It was an essay discussing the strengths of private equity using an agency theory perspective.

Following this essay, numerous studies about private equity and its effects on buyout firms have been published, with the majority focusing on markets in the United

States and the United Kingdom. Although existing research has focused on a variety of issues, three important topics are of repeated interest: i) the analysis of selection criteria of private equity funds, ii) the impact of private equity on post buyout performance and efficiency, and iii) the determinants of performance increases for

2

Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

16 - 17 December 2013, Hotel Mariiott Casamagna, Cancun, Mexico, ISBN: 978-1-922069-38-2 companies following a buyout. Table 1 provides an overview of the existing studies, the geographic scope of the data, the variables included, and the key findings.

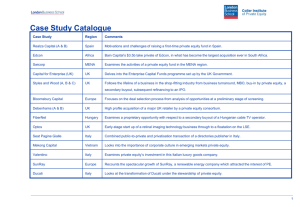

<Insert Table 1 about here>

2.1 Selection Criteria of Private Equity Funds

Regarding the analysis of selection criteria of private equity funds, existing studies have come to conflicting conclusions. Lichtenberg and Siegel (2009) found evidence that prior to acquisitions, buyout plants are more efficient than their peers and outperform competitors. Harris et al. (2005) concluded the opposite: that prior to acquisitions, buyout plants are less productive and efficient than their peers. One potential supposition to draw from these conflicting results is that private equity has evolved and diversified in recent years. This is the case in numerous industries, as private equity has shifted from investing primarily in mature and cash-rich companies, to financing technology-based companies and restructuring inefficient firms.

A more recent study by Nordström and Wiberg (2009) uses a sample of

European buyouts and a discrete choice framework in order to predict the probability that a company will be selected for a buy-out by a private equity fund. Using numerous selection criteria in order to account for different buyout strategies among private equity firms, they conclude that the evolution and growth of the company, as measured by forward changes of key financial indicators such as sales, EBITDA-

Margin and leverage, had a larger impact on the probability of a buyout than did the initial size or current success of the company. Based on this, they concluded that private equity funds tend to choose companies with three key factors: a) growing companies, as measured by increases in sales and number of employees, b) companies that have the potential to improve efficiency, as measured by EBITDA-

Margin prior to the buyout, and c) companies that have small initial debt.

2.2 Impact of Private Equity on Performance and Efficiency

On the other hand, studies that examined the impact of private equity on post buyout financial performance and efficiency tend to have more conclusive results. The majority of these studies indicate that following a buyout, firms improve both plant efficiency and profitability. Kaplan (1989) conducted one of the earlier studies regarding post-buyout financial performance. By examining 76 large buyouts between 1980 and 1986, this study finds that following a buyout, companies are able to increase their operating income and net cash flows while decreasing capital expenditures. A similar study conducted by Bergström et al. (2007) uses data from

Sweden to show that private equity has a significant positive effect on the EBITDA-

Margin. Other studies examine the effects of private equity on efficiency, and come to similar conclusions. Studies by Lichtenberg and Siegel (1990), Amess (2002), and

Siegel and Wright (2005) all show a significant positive relationship between buyouts and subsequent plant productivity.

While it is often argued that private equity funds exploit corporate resources by laying-off workers and cutting crucial investments, these charges have yet to be

3

Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

16 - 17 December 2013, Hotel Mariiott Casamagna, Cancun, Mexico, ISBN: 978-1-922069-38-2 proven by empirical results. The majority of existing research, including a study by

Bergströmet et al. (2007), found no evidence of a reduction in the number of employees or in wage levels after a buyout. Furthermore, Lerner et al. (2008) used

OLS regressions to study the effect of private equity on research and found that the patents of private equity-backed firms are more frequently cited and are more efficiently concentrated on the core strengths of the company. These results challenge the widely spread belief that high leverage is contradictory to innovation.

2.3 Determinants of Performance Increases Following a Buyout

While many of the studies show consistent results about the effect of private equity and performance, the determinants of positive changes in performance for companies following a buyout remain unclear. Kaplan's (1989) attempt to explain performance improvement by reduced agency costs has been broadened by a study by Phan and Hill (1995). This study indicates that changes in the governance structure of private equity-backed firms often lead to reduced hierarchical complexity and increased decentralization. While this often reduces agency costs, it is not the only factor in explaining positive firm performance following the buyout. To conduct a more in-depth analysis, other authors have added additional variables to the discussion. Seth and Easterwood (1993) point out the role of strategic redirection towards related businesses. Harris et al. (2005) focus on the role of operational changes, including the labor intensity of production, the outsourcing of intermediate goods, and the increase in economic efficiency. Scholes (2009) shows that following the acquisition, by encouraging a shift toward increased efficiency and growth, private equity has a strong positive impact on former family-owned firms. In a study about buyout determinants using a large panel of North-American and European companies, Kreuter et al. (2005) find that in addition to industry-related and company-specific factors, the experience of the underlying private equity fund and the origination of the buyout deal significantly affect the subsequent performance of a buyout. These results have been confirmed by Cornelli and Karakas (2008) and by

Acharya et al. (2009). Both concluded that the intensity of private equity fund involvement positively impacts the buyout firm.

Although the studies mentioned thus far illustrate some of the determinants of positive changes in performance for companies following a buyout, the difficulty of determining specifically how each variable affects the company remains a crucial concern. A study by Bergstöm et al. (2007) concludes that while buy-out firms typically perform better than their non-buy-out rivals, there is no clear proof of a relationship between typical private equity mechanisms, such as increased leverage of ownership, and subsequent firm performance. According to the authors, this is due to complexity issues. They state that the "value creation process" would be "complex and poorly proxied by a few variables that are relatively easily measured". Thus the problem of determining private equity influences is based on the underlying problem of properly identifying performance determinants. In one of the most cited studies by

Child (1974) that finds no apparent relationship between size or concentration of ownership and performance. However, this study does conclude that a focus on short-term profitability and on payment of dividends is negatively related to profitability.

4

Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

16 - 17 December 2013, Hotel Mariiott Casamagna, Cancun, Mexico, ISBN: 978-1-922069-38-2

2.4 Problems Applying Existing Research to the French Market

The majority of existing research regarding private equity and buy-out companies has been conducted in a U.S. or U.K. context. However, while certain mechanisms of private equity are efficient in the U.S. or U.K., these mechanisms may not be efficient in France. This is due to the specifics of the French economy and the French private equity industry. By studying the relationship between private equity and company performance in a solely French context, it is possible to draw conclusions about which mechanisms of private equity affect French competitiveness and their significance in the French economy.

To begin, it is necessary to examine the origination of private equity and the manner in which it has evolved and spread over time. The first buyouts involving high levels of financial leverage occurred in the U.S. in the early 1980s. While the first highly-leveraged investments concentrated mostly on large public-to-private transactions in the manufacturing and retail sector, leveraged buyouts have since diversified and spread over numerous industries. Private equity fund investment in the U.S. has increased from $0.2 billion in 1980 to over $200 billion in 2007 (Kaplan and Strömberg, 2008). However, these numbers fluctuate significantly within that time period, peaking in 1988, 1998 and 2006. The first decline of private equity occurred in the late 1980's when private equity funds began to invest in mid-sized firms. As opposed to investment in the mature industries, as was typical prior to

1980, sectors including information technology, media, telecommunications, financial services and health care began to experience a growth in the number of buyouts.

(Kaplan and Strömberg, 2008). In many cases, secondary and even tertiary buyouts of the same firm became frequent.

The U.S. and U.K. private equity industries dominated the market between

1985 and 1989, accounting for 90% of transactions worldwide. Since then, private equity has expanded in Western Europe, which today makes up 50% of total investments (Kaplan and Strömberg, 2008). The French private equity market has developed more recently, and the economic and legal conditions affecting this market differ significantly from the markets of the U.S. and U.K. Therefore, the private equity mechanisms that are successful the specific economic and legal conditions of the U.S. or U.K. may or may not be successful under different conditions. Therefore, it cannot be assumed that studies involving the U.S. or U.K. will not perfectly apply to France. One of the important differences of the French economy is prevalence of relatively poorly-performing mid-sized companies. As

Glachant et al. (2008) emphasized, France has a limited number of mid-sized companies that can innovate and operate on an international scale. The authors relate this phenomenon to the illiquid French market, where it is difficult to access sufficient financing. In consequence, small and mid-sized French companies, on average, are smaller and more fragile, experience more bankruptcies, export fewer products and grow more slowly than their homologues in the U.S. or U.K. (Glachant et al., 2008).

The economic differences between these countries are highly pronounced and researchers have taken notice. Desbrières and Schatt (2002) question the validity of approaches developed overseas for the French market. They state, "one

5

Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

16 - 17 December 2013, Hotel Mariiott Casamagna, Cancun, Mexico, ISBN: 978-1-922069-38-2 may wonder whether the theory developed by Jensen (1989) concerning American buy-outs is valid within the French context". In their study about the effects of private equity on operating performance of French targets, they note the differences between buyouts in the U.S. or U.K and in France. The authors state that buyout operations in France are financed with less leverage (senior debt makes up 50-60% of the enterprise value in France compared with 85% in the US), but enjoy greater involvement by management and financing banks, both of which actively participate in the strategic and financial control of the company. Comparing the distribution of shareholder types prior to a buyout, Desbrieres and Schatt (2002) conclude that

LBOs in the US could "be analyzed basically as a feature of the market for corporate control of firms with dispersed share ownership", as the majority of the buyouts are divisional spin-offs of large corporations (64% of buyouts). However, in France, buyouts of family firms are more frequent (55% of buyouts). This questions the effectiveness of U.S. and U.K. private equity mechanisms on French target companies, since French companies are "already characterized by a considerable concentration of ownership." (Desbrieres and Schatt, 2002). Finally according to

Desbrieres and Schatt, the predominant role of family-owned companies also presents a greater risk to the success of a leveraged buyout. This is because when the founding manager exits the company, value is lost in terms of insider information, business connections and know-how. In contrast to these assumptions, Boucly et al.

(2009) argue that the prevalence of family-owned firms in France is instead very positive for the French private equity market, as the main problem for these companies is that they lack sufficient financial means. In this case, private equity firms must only invest money in these companies in order to reap the performance rewards.

France is the second largest private equity market in Europe with 0.5% of

GDP invested in buyouts. France is also the second largest European country in terms of market capitalization as % of GDP. France has a high percentage of small and mid-sized companies (SMEs), in comparison to the other selected countries.

The high percentage of SMEs leads to a lower average monetary value of private equity investment per transaction. In the UK, funds spend on average 13 M EUR on a deal, while in France funds spend on average only 6 M EUR. Additionally, banks and insurance companies are some of the largest investors in France, while pension funds and funds of funds are larger in the UK.

While taking into account the specificities of the French economy, France represents an attractive market both for private equity funds as well as for potential target companies. This is because there are numerous opportunities available for value creation, both in terms of the consolidation of small companies and the improvement in efficiency of family-owned companies. Private equity funds benefit from a broad base of target companies that may already enjoy competent management, but simply lack sufficient financial means. Funds also benefit from a more patient culture of investors who are less concerned with a rapid turn-around in financial performance, as compared to investors in the U.S. or U.K. While France is an attractive market, two of the most important mechanisms of private equity in a

U.S. and U.K. context (as discussed above) are not as applicable in France. These mechanisms include pressure through high financial leverage and the concentration and decentralization of governance. Therefore, if French buyout companies show a

6

Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

16 - 17 December 2013, Hotel Mariiott Casamagna, Cancun, Mexico, ISBN: 978-1-922069-38-2 significant increase in performance compared with their non-buyout peers, this may show that the effects of leverage and changes in the governance structure are potentially over-estimated in France. Instead, the management expertise of the fund may be the determining factor in subsequent performance.

3.0 Empirical Methodology

3.1 Data

The data collected for this analysis includes a sample of all leveraged buyouts between January 1, 2003 and January, 1 2007 that involved a French target company and for which financial accounting information is available. The data are retrieved from the Zephyr Database, which contains information about mergers and acquisitions in Europe, Asia and the U.S.

In order to extract the relevant buyouts, the following selection criteria have been used. First, French deals that involve a high amount of leverage have been chosen. This includes institutional buyouts involving a private equity fund, management buy-in operations, which involve a management team external to the buyout firm and management buy-outs, which involve the company’s existing management team. Based on these selection criteria, the Zephyr Database returned

719 results. Since this number includes also divisional buyouts, which involve buyouts of branches or subsidiaries of companies, it has been verified that each of these companies had a unique identifying code as determined by the target BvD ID number. If no unique code is identified, it is assumed that the buyout concerns divisional buyouts and should not be included in the sample. After removing divisional buyouts there are 636 results.

The next step involves accessing the target financial information to construct a peer group. The accounting information of the target companies has been retrieved from the Orbis Database, which contains the unconsolidated accounts of companies worldwide from 2001 to 2010. For French companies the Orbis data are based on the Diane Database, which retrieves accounting information directly from the French

Statistical Office. The financials for each target company have been found in this database using the BvD ID numbers. Financial information for 502 target companies has been retrieved from the Orbis Database. In order to compare company information to that of their non-buyout twins, a peer group for each target company has been constructed. The peer group is based on the four-digit industry NACE-

Code and company size. Only companies for which financial data is available are considered. On average 8 twin companies have been identified for each target company, for a total of 4140 twin companies. The distribution of buyouts per year is displayed in Table 2. This distribution relatively equally spread.

<Insert Table 2 about here>

Table 3 provides a comparison between the sample collected from the

Zephyr Database and the data available from the French Private Equity Association

(AFIC). Regarding the number of employees, which can be used as a proxy for the size of the company, the distribution of the sample equals the distribution of all

French private equity deals, with a slight overrepresentation of mid-sized deals (35% in this sample compared to 26% in all of France).

7

Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

16 - 17 December 2013, Hotel Mariiott Casamagna, Cancun, Mexico, ISBN: 978-1-922069-38-2

<Insert Table 3 about here>

Use of the Zephyr and Orbis Databases provide several advantages and allow this study to avoid two selection biases found in U.S. and U.K. studies. First,

U.S. and U.K. studies often use information obtained directly from private equity funds. However, this data is often only provided by high performing private equity funds willing to share their information. The second selection bias often found in U.S. and U.K. studies is that detailed information, such as leverage, EBITDA-multiples, is often unavailable for certain buyouts. The availability of such information depends largely on the public interest in the deal and the willingness of the involved parties to share information. This leads to a bias in favor of successful deals and secondary buyouts.

3.2 Variables

Several variables are included in the empirical models. These include sales growth, EBITDA-Margin, changes in working capital, and return on assets. The

EBITDA-Margin shows the effects of private equity independently from the financing structure of the company. Cash-flows and the return on assets are two measures that are of high interest for shareholders. Therefore, private equity funds have strong incentives to increase these indicators. The numbers of employees, the absolute value of equity and the absolute value of sales are used as a proxy for the company size. The change in the number of employees and the change in working capital provide some indication about changes in performance.

A snapshot of the performance indicators of the target companies and industry peers during the acquisition year is in presented in Table 4. As shown, there are significant differences between private equity target companies and their industry peers. The data shows the concentration of the French private equity market around mid-sized buyouts. Target companies are typically smaller in size than the industry average in terms of sales, EBITDA, Cash-Flow, number of employees, amount of equity, debt and working capital.

On the other hand, the return on capital employed varies widely among buyout companies. This could be an indication that the two main strategies for the selection of target companies in the U.S. and U.K. context, which are either choosing the industry leader or choosing an under-performing company, are applicable in the

French private equity industry as well.

<Insert Table 4 about here>

3.3 Empirical Model

To analyze the impact of private equity on subsequent firm performance, a comparison between buyouts companies and their peers is conducted in two steps.

First, in order to determine the selection criteria of private equity funds, a Logit Model is used. This model analyzes empirically the likelihood of a private equity investment based on several company factors. The logistic regression model permits an empirical assessment of the relationship between a private equity investment and potential selection criteria used by private equity funds. The model (equation 1) shows that the probability at of a company being selected at time t depends on the

8

Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

16 - 17 December 2013, Hotel Mariiott Casamagna, Cancun, Mexico, ISBN: 978-1-922069-38-2 number of employees (as proxy for company size), the EBITDA-Margin, the Cash-

Flows, the debt and the return on assets in the year when the buyout was completed. By including lagged independent variables, the model also shows the evolution of employees, EBITDA-Margin, Cash-Flows, and return on assets throughout the three years prior to the buyout.

It is predicted that the model will generate a negative relationship between

EBITDA-Margin, the absolute number of employees, the level of debt and the probability of a buyout. In contrast, growth in number of employees prior to the buyout should be correlated positively with a buyout.

Next, the effects of private equity on operating performance are tested using a multivariate regression. For each regression, the compound annual growth rate of each performance indicator over the three years following the buyout is tested against the impact of private equity and the other performance indicators.

The equation for sales growth, for example, is:

The results are predicted to show significant correlations between a private equity investment and EBITDA-Margin, the return on assets, sales growth, working capital and the number of employees.

4.0 Empirical Results and Analysis

The first part of the analysis concerns the relationship between selection criteria used by private equity funds and the probability that a company will be chosen for a buyout. The results of the Logit model are presented in Table 5. As demonstrated, several variables increase the probability of a buyout. According to the results, a company is more likely to experience a buyout if it has a large number of employees (a proxy for size) and is performing better than its competitors in terms of return on assets. Cash flow has a small but significant positive effect on the probability of a buyout. Other variables show direction but cannot be quantified.

<Insert Table 5 about here>

Based on the results, this model relates to the conclusions drawn by

Nordström and Wiberg (2009), particularly to their statement that companies are more likely to be chosen for a buyout if they are experiencing high growth in number of employees relative to their peers. However, while Nordström and Wiberg (2009) deduced that the change or growth in company factors, such as number of employees, has the largest impact on the probability of a buyout, the results of this

9

Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

16 - 17 December 2013, Hotel Mariiott Casamagna, Cancun, Mexico, ISBN: 978-1-922069-38-2 analysis show that initial absolute size may be more important. While this analysis does provide evidence that growth in the number of employees is positively related to private equity investment, the variable is not statistically significant.

In addition, this analysis provides evidence to disprove the argument that private equity funds prefer small companies over larger ones, and that the probability of a buyout is negatively related to initial company size. As previously mentioned, this analysis shows instead that the probability of a buyout is positively related to initial company size, as companies with a large number of employees relative to their peers are more likely to experience a buyout.

Furthermore, the data show that the probability of a buyout increases as a company’s performance relative to its competitors increases. Therefore, this analysis contradicts existing theories that funds choose underperforming companies. On the contrary, the results show instead a positive relationship between high EBITDA-

Margin and the probability of a buyout. However, this relationship cannot be quantified as the variable is not statistically significant.

The second part of the analysis concerns the relationship between private equity investment and subsequent firm performance. The multivariate regression is presented in Table 6. Based on the results, there is no conclusive evidence that a private equity investment leads to a subsequent increase in performance indicators for the buyout company, specifically in terms of EBITDA-Margin growth and return on assets. At the same time, private equity funds typically choose companies with a higher ROTA than their peers. A positive change in ROTA prior to a buyout is correlated with positive performance after a buyout, but cannot be attributed to the private equity investment. On the contrary, the private equity investment has a negative impact on the ROTA of even positively performing companies.

<Insert Table 6 about here>

In addition, the results of this analysis show that private equity has a negative impact on all indicators representing growth for the buyout firm. Companies experience decreasing sales, decreasing cash-flow and negative employee growth following a buyout. Also, no evidence can be found for an improvement in efficiency.

While the number of employees decrease following a buyout, this cannot be interpreted as an improvement in efficiency given the simultaneous decrease in sales and cash-flow. Moreover, there is no significant correlation between private equity investment and working capital. Lastly, when controlling for the target company industry code, the results of all models remain unchanged.

4.1 Limitations

There are two main limitations of the study. First, detailed information is not often available regarding the funds involved, the enterprise value and the amount of leverage. An attempt to collect more information through the French Journal "Les

Echos" was inconclusive due to a small sample size. Second, the Orbis Database contains only unconsolidated financial data. While Zephyr relates a deal only to one company, private equity funds often make changes in the structure of a company’s holdings and subsidiaries. This creates a bias when determining how to compare a company’s performance before and after a buyout, as the makeup of the company

10

Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

16 - 17 December 2013, Hotel Mariiott Casamagna, Cancun, Mexico, ISBN: 978-1-922069-38-2 may be calculated differently depending on the fund. This problem has been addressed by Gaspar (2009), and the bias was reduced by comparing the information available from the Diane Database to information available on other databases, in the press and on the company’s website. The data used in this study could not be double-checked on a case-by-case basis.

5.0 Conclusion

The French private equity market is rapidly expanding as private equity becomes an increasingly important source of financing for French companies. The

French market offers attractive target companies and the potential for strong increases in performance. However, it is necessary to consider the differences in the

French economy that may render inefficient the standard private equity mechanisms employed in the U.S. and U.K. In order to analyze the specificities of the French market, this paper has addressed two related topics. The selection criteria used by private equity funds in the French market was discussed and analyzed, as well as the impact of private equity on subsequent firm performance.

As demonstrated by existing research, investment involving a private equity fund and a high amount of leverage affects a company and its competitiveness.

However, existing studies of the French private equity market are inconclusive with regard to identifying the specific explanatory factors of private equity as they relate to subsequent firm competiveness. Therefore, this paper has offered more conclusive evidence, particularly by confirming the majority of the results obtained by

Desbrières and Schatt (2002).

Based on the quantitative analysis, the majority of French private equity funds use similar selection criteria when choosing buyout firms. As shown, the probability of a buyout increases as initial company size and return on capital employed increases. This corresponds with the classic strategy of targeting the best performing companies in an industry in order to minimize the risk involved in the buyout operation. The results have also shown that there is no significant change in company performance following a private equity investment. However, companies do tend to decrease in size following a buyout, possibly due to employee lay-offs or an attempt to increase efficiency. As funds typically choose companies that are already larger than the industry average and have a higher than average return on capital employed, it may be difficult for funds to continue to improve performance growth at a continuous rate. In addition, due to high financial leverage, the buyout is typically able to generate value without a significant improvement in company performance indicators. These results parallel the existing theory that not all private equity funds become actively involved in the target company's management in order to improve performance.

Furthermore, the results of the analysis contradict the theory that value is created by private equity funds. On the contrary, buyout companies experience a significant decrease in sales and number of employees after a buyout, but do not experience a significant improvement in efficiency. The lack of improvement in performance following a private equity investment in France contradicts studies of buyouts in the U.S. and U.K. This shows that leverage and changes in governance

11

Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

16 - 17 December 2013, Hotel Mariiott Casamagna, Cancun, Mexico, ISBN: 978-1-922069-38-2 appear to be among the most effective mechanism of private equity in order to increase firm performance in the U.S. and U.K. However, when employing these mechanisms in a French context, the performance of French buyout companies does not improve. In order to fully determine why private equity mechanisms in the U.S. and U.K. do not have the same impact in France, a more detailed analysis of private equity must be conducted. Further analysis must consider additional variables, such as the level of the fund's involvement in the project or changes to company goals.

References

Acharya V., Hahn M. and Kehoe C. (2009), “Corporate governance and value creation: Evidence from private equity”, Stern School, New York University, working paper, pp. 61 .

Amess K. (2002),

“Management Buyouts and Firm-Level Productivity: Evidence from a Panel of UK Manufacturing Firms”, Scottish Journal of Political Economy,

Vol. 49 No. 3, pp. 304-317 .

Berg A. and Gottschalg O. (2004), “Understanding Value Generation in Buyouts”,

European Venture Capital Journal, Vol. 114, pp. 2-4 .

Bergström C., Grubb M. and Jonsson S. (2007), “The operating impact of buyouts in

Sweden: A study of value creation”,

The Journal of Private Equity, Vol. 11, pp. 22-39 .

Beroutsos A., Freeman A. and Kehoe C. (20 07), “What public companies can learn from private equity”, McKinsey on Finance, H.22, 1-6.

Boucly Q., Thesmar D., Sraer D. (2009), “Leveraged Buyouts – Evidence from

French Deals”, World Economic Forum, working paper, pp. 63-77.

Buzzell R. and Gale B. (1987), The PIMS principles: linking strategy to performance ,

The Free Press, New York.

Child J. (1974), “Managerial and organizational factors associated with company performance”, Journal of Management Studies , Vol. 11, pp. 73-189 .

Cornelli F. and Karak as O. (2001), “Private equity and corporate governance: Do

LBOs have more effective boards?”,

London Business School, working paper, pp. 36 .

Desbrières P. and Schatt A. (2002), “The Impacts of LBOs on the performance of acquired firms: the French case”,

Journal of Business Finance & Accounting,

Vol. 29 No. 5, pp. 695-729.

Dibb S., Simkin L., Pride W. and Ferrell O.C. (1994), “Marketing concepts and strategies”,

Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Gaspar J. M. (2009), “The Performance of French LBO firms: new data and new results”, Essec, working paper, pp. 55.

Glachant, J., Lorenzi, JH. and Trainar P. (2008), “Private equity et capitalisme français”, rapport du Conseil d’Analyse Economique,

No. 75, pp. 329.

Harris R., Siegel D. and Wright M. (2005), “Assessing the impact of management buyouts on economic efficiency: plant-level evidence from the United

Kingdom”,

the Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 87, pp. 148-153 .

Jensen M. (1989), “Eclipse of the Public Corporation”, Harvard Business Review,

Vol. 89, pp. 61-74.

Kaplan S. and Strömberg P. (2008), “Leveraged buyouts and private equity”,

National Bureau of Economic Research, University of Chicago, working paper, pp. 42.

12

Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

16 - 17 December 2013, Hotel Mariiott Casamagna, Cancun, Mexico, ISBN: 978-1-922069-38-2

Kaplan S. (1989), “The effects of Management Buyouts on operating performance and Val ue”,

Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 24 No. 2, pp. 217-254.

Kester C. and Luehrman T. (1995), “Rehabilitating the leveraged buyout”, Harvard

Business Review, pp. 119-130.

Kreuter B., Gottschalg O. and Zollo M. (2005), “Truths and Myths about

Determi nants of buyout performance”,

Insead, working paper, pp. 10.

Lerner J., Sorensen M. and Strömberg P. (2008), “Private Equity and long-run investment: The case of innovation”, Harvard Business School, working paper, pp. 50.

Lichtenberg F. and Siegel D. (1

990), “The effects of leveraged buyouts on productivity and related aspects of the firm behavior”, Journal of Financial

Economics, Vol. 27, pp. 165-194.

Nordström L. and Wiberg D. (2009), “Determinants of Buyouts in Private Equity

Firms”, Centre of Excellence for Science and Innovation Studies, working paper, pp. 25.

Phan P. and Hill C. (1995), “Organizational Restructuring and Economic

Performance in Leveraged Buyouts: An Ex Post Study”, Academy of

Management Journal, Vol. 38, pp. 704-739.

Rappaport A.

(1990), “The staying power of the public corporation”,

Harvard

Business Review, pp.96-104.

Scholes L., Wright M., Westhead P., Bruining H. and Kloeckner O. (2009), “Family-

Firm Buyouts, Private Equity, and Strategic Change”,

The Journal of Private

Equity, vol. XII, no. 2, 7-18.

Seth A. and Easterwood J. (1993), “Strategic redirection in large management buyouts: the evidence from postbuyout restructuring activity”, Strategic

Management Journal, 14(4), 251-273.

Wright M., Hoskisson R., Busenitz L. and Di al J. (2000), “Entrepreneurial Growth through Privatization: The upside of Management Buyouts”, Academy of

Management Review, 25, 591-601.

Wright M., Hoskisson R., Busenitz L. (2001), “Firm Rebirth: Buyouts as Facilitators of

Strategic Growth and Entrepre neurship”, Academy of Management

Executive, vol. 15 no.1, 691-702.

Table 1: Summary Overview of the Empirical Investigations of Buyout Effects on Company Performance

Study Dependent Variable Country Key findings

Nordström

(2009)

Boucly et al.

(2009)

Acharya et al.

(2009)

Lerner et al.

Probability of

Buyout Dummy

Nordic

Europea n Market

The probability of buyout depends on the change in number of employees, the debt/equity ratio and EBITDA-

Margin.

Operating performance, ROA, asset growth, working capital needs

France Private equity has a positive impact on growth in sales, assets and employment. Private equity funds act as a substitute for weak capital markets.

EBITDA-Margin,

Margin Growth,

Sales, EBITDA multiple

Indicators of

UK

US

Investments of mature private equity houses realize better investment performances as investments in the stock market. The better performance is achieved thanks to an improvement of EBITDA-Margins and of EBITDA multiples at the time of exit.

Patents of private equity-backed firms are more frequently

13

Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

16 - 17 December 2013, Hotel Mariiott Casamagna, Cancun, Mexico, ISBN: 978-1-922069-38-2

(2008) patents for buyout companies cited. The firms’ patent portfolio becomes more focused after a buyout.

Bergström et al.

(2007)

Kreuter et al.

(2005)

Harris et al.

(2005)

Desbrières

(2002)

Phan (1995)

EBITDA-Margin Sweden Private equity has a significant abnormal positive impact on EBITDA-Margin, but there is no evidence for a positive impact of leverage and management ownership.

Weighted realized gross Internal Rate of Return

North

America

+

Europe

A short holding period, either a very small or very large size of companies, a positive stock market performance, the industry average EBITDA-margin, a low EBITDAmargin of the company prior to the buyout, negative revenue growth over the holding period, the involvement of an experienced private equity fund, a proactive deal origination and a medium level of management equity ownership all have a positive effect on buyout performance.

Pre- and postbuyout dummies

Accounting indicators such as return on Equity, capital structure or margin ratios

UK MBO plants are less productive than comparable plants before the transfer of ownership. After a buyout companies experience a substantial increase in productivity.

France MBO targets in France perform better than their industry peers. The buyout companies perform less well than their peers after the buyout in terms of return on equity, return on investment and margin ratios.

Private equity investments induce changes in firm goals, strategy and structure, which lead to greater efficiency.

Seth (1993)

Change in goals, organization and performance

US

Classification of a firm's diversity type

US

Lichtenberg

(1990)

Kaplan (1989)

MBO dummy variable of plants in year t

Changes in operating income, capital expenditures and net operating cashflow

US

US

Buyouts appear to be vehicles for focusing the strategic activities of the firm towards the more related businesses;

This reorganization contributes to firm-level performance and social efficiency.

Buyout plants are more efficient than non-buyout plants prior to the acquisition and increase their mean productivity even more after a buyout. This is especially true for operations where the management is involved.

Reduced agency costs for the buyout companies lead to an increased operating income and net cash-flows while capital expenditures decreased.

Table 2: Distribution of Deals by Entry Years

Years

Entry

2003

65

2004

120

2005

118

2006

144

2007

55

Total

502

14

Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

16 - 17 December 2013, Hotel Mariiott Casamagna, Cancun, Mexico, ISBN: 978-1-922069-38-2

Table 3: Benchmarking of Sample by Distribution of Deal Size

Sample

Number of companies

% of total

Number of companies

0-99

166

55.3%

Number of employees

100-

999

1000 and

+

105

35.0%

29

9.7% total

300

906 345 92 1343

French PE % of total 67.5% 25.7% 6.9%

Table 4: Financial Indicators PE-targets and Sector Average

Variable mean median std.dev. max min deal coverage

03 - 06

5.5% t-stat of diff with sector deal sales sector average sales deal EBITDA sector average EBITDA deal Cash-Flow sector average Cash-Flow deal Employee nb sector average Employee nb deal equity sector average equity deal debt sector average debt

14533

88238

1171

11544

1005

9295

72

388

1226

14621

673

14869

6815 31796 993381

17345 207931 1951072

395

1670

0

0

3825 115163 -23680

47803 628268 -37596

311

1474

34

77

6095

42960

182

934

266359

407657

4494

8024

-136358

-269503

1

1

207

1976

0

0

12250 212592 -637040

69517 1275981 1

9691 519172

132549 2516779

0

0 deal working capital sector average working capital deal ROCE sector average ROCE deal ROTA

2219

10707

24

30

10

664

1939

22

22

8

12249 626570 -77441

45605 621318 -134766

51

43

13

598

331

93

-930

-257

-89

-100 sector average ROTA 10 9 18 92

Note: All values in th US$, except ROCE and ROTA, significance level ** p<0.05

19,7**

9,4**

8,2**

16,8**

6,6**

3,2**

11,1**

31,2**

47,7**

15

Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

16 - 17 December 2013, Hotel Mariiott Casamagna, Cancun, Mexico, ISBN: 978-1-922069-38-2

Table 5: Probability of a Buyout Based on Performance Indicators

Logit

Number of

Employees

ROTA

EBITDA-Margin

Cash-flows

Debt

CAGR

EBITDA-Margin pre-buyout

CAGR

Cash-flows pre-buyout

CAGR

Employees pre-buyout

CAGR

ROTA pre-buyout

Constant

/lnsig2u

Number of observations

0.002***

(6.046)

0.027***

(3.782)

0.330

(1.377)

0.000***

(2.681)

0.009

(0.361)

-0.070

(-0.448)

-0.065

(-0.526)

0.049

(0.088)

0.009

(0.085)

-3.126***

(-20.509)

1,766 note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Random Effects

Logit

(-0.300)

0.437

(0.705)

-0.022

(-0.187)

-3.339***

(-14.242)

0.576*

(1.797)

0.002***

(5.183)

0.032***

(3.893)

0.360

(1.231)

0.000***

(3.051)

-0.000

(-0.010)

-0.100

(-0.617)

-0.038

1,766

Rare Events Logit

(-0.401)

0.179

(0.236)

-0.005

(-0.044)

-3.114***

(-18.287)

0.002***

(3.142)

0.027***

(3.534)

0.363

(1.293)

0.000

(1.128)

0.016

(0.562)

-0.062

(-0.307)

-0.079

1,766

16

Proceedings of International Business and Social Sciences and Research Conference

16 - 17 December 2013, Hotel Mariiott Casamagna, Cancun, Mexico, ISBN: 978-1-922069-38-2

Table 6: Analysis of PE Impact on Growth Variables

Sales

Growth

EBITDA

Margin

Growth

Cash flow

Growth

Employee s Growth

ROTA growth

Working

Capital growth

Private Equity

Dummy

Number of

Employees

ROTA

EBITDA-

Margin

Cash-flows

Debt

CAGR

EBITDA-Margin pre-buyout

CAGR

Cash-flows pre-buyout

CAGR

Employees pre-buyout

CAGR

ROTA pre-buyout

Constant

Number of observations

Adjusted R2

-0.040***

(-3.362)

-0.000**

(-2.135)

-0.001

(-1.428)

0.006

(0.233)

0.000

(0.735)

-0.122*

(-1.746)

-0.000

(-1.221)

0.004**

(2.198)

-0.051

-0.002** -0.000 0.006

(-2.252)

0.007

(0.910)

-0.002

(-0.295)

0.103**

(2.372)

0.001

(0.294)

0.125***

(14.116)

1,766

0.015

-0.025

(-0.361)

0.000

(0.786)

0.002

(1.190)

0.023

-0.038***

(-3.130)

-0.000**

(-2.242)

0.000

(0.586)

0.033

(0.454) (-0.503) (0.818)

-0.000 0.000**

(-0.714) (2.237)

(-0.072) (1.626)

0.141*** 0.063

(3.110)

0.070

(1.531)

0.046

(0.255)

0.047*

(1.926)

-0.035

(-0.910)

1,766

0.040 note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

(1.438)

0.191***

(4.522)

0.092

(0.701)

0.026

(1.242)

-0.086**

(-2.396)

1,766

0.082

0.000***

(3.134)

-0.001

(-0.689)

-0.003

(-0.534)

0.003

(0.396)

1.076***

(23.215)

0.004

(1.579)

0.030***

(4.516)

1,766

0.499

-0.071

(-0.881)

0.000

(0.447)

0.010***

(5.042)

-0.162***

(-3.682)

0.000

(0.833)

-0.023**

(-2.466)

0.028

(0.761)

0.051

(1.463)

0.160

(1.153)

0.143***

(4.897)

-0.338***

(-8.322)

1,766

0.050

-0.091

(-1.056)

0.000

(1.394)

0.008**

(2.341)

-0.921*

(-1.955)

-0.000

(-0.654)

-0.000

(-0.034)

-0.015

(-0.207)

0.050

(0.783)

-0.284

(-1.374)

0.026

(0.884)

-0.044

(-0.880)

1,766

0.071

17