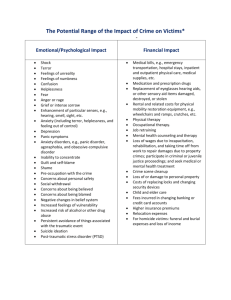

Victimhood

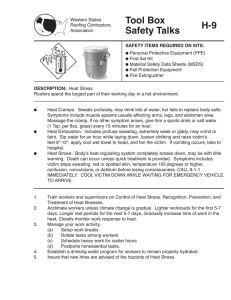

advertisement