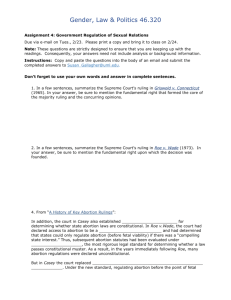

Roe v. Wade Capricious Test? I. I

advertisement