The Elusive Foreign Compact I. I

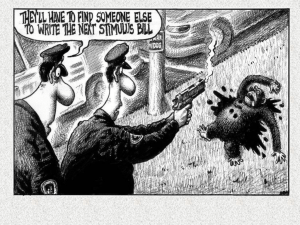

advertisement