Proceedings of World Business Research Conference

advertisement

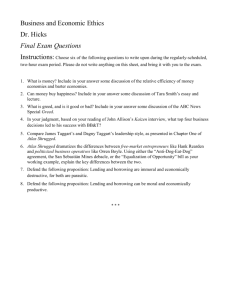

Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 Allocating Credit Borrowing Quantities through Analytical Hierarchy Process and Linear Optimization Feng Jiao1, Jingxin Dong2 and Christian Hicks3 Companies apply commercial credits from a multiple source, which involves traditional lenders as banks and traders, and a new emerging lender known as third party logistics (3PL) companies. In addition, credit selection is affected by both qualitative and quantitative concerns, which is treated as a multiple criteria problem. This problem forces companies to evaluate their concerns’ importance before selecting lenders. Therefore, two questions are raised: What is priority ranking of borrowers’ basic concerns in borrowing credits? How much should be allocated to borrow from these three credits with considering the high importance concerns? In this article, an integrated method of using analytic hierarchy process (AHP) and linear programming (LP) is presented. The method aims to measure the importance of borrowers’ concerns, and issue one LP model for placing optimal borrowing quantities with constraints of important criteria. This method can be applied to different borrowers to allocate their borrowing arrangement with specific distinct considering criteria. Field of Research: Logistics Finance 1. Introduction Companies are more or less budget constrained. Therefore, commercial credit is important and necessary for their survival. Banks as a traditional lender, absorb savings from public and lend part of capital to enterprises (Rosenberg, 1993). Bank offers different categories of credits to companies in financial market (Cook, 1999). However, rigorous application criteria, uncertainty of approval time, and high failure rate lead many companies to abandon their borrowing applications with fear of rejection (Eurosystem, 2014). Trade credit contributes another reliable approach for credit borrowers. It takes a main role for offering short-term credit in commercial credit market (Wilner, 2000). As a credit maintained by trust between lenders and borrowers, it has a more flexible payback period and a negotiable interest rate comparing with bank credit (Wilson and Summers, 2002). However, bank and trade credit have been pointed out the weakness in monitoring the transactions of products. This situation can be relieved by a service called Integrated Logistics Financial Service (ILFS). ILFS works through a third party logistics (3PL) company allies with traditional financial institutions to provide credits and monitor borrowers’ business (Xiangfeng Chen and Cai, 2011). Although some literatures imported a new credit which is called 3PL credit (Xiangfeng Chen and Wang, 2012), they only contributed a debate for explaining 3PL credits’ profit making to borrowers. While borrowers’ concerns in selecting 3PL credit have been ignored. As the description of Christina E. Bannier et al. (2012), credit selection is a process influenced by both tangible and intangible factors. Furthermore, 1 Feng Jiao, Newcastle University Business School, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, NE1 4SE. Email: f.jiao@newcastle.ac.uk 2 Dr Jingxin Dong, Newcastle University Business School, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, NE1 4SE. Email: jingxin.dong@newcastle.ac.uk 3 Prof. Christian Hicks, Newcastle University Business School, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, NE1 4SE. Email: chris.hicks@ncl.ac.uk 1 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 companies in reality consider credit selection as a multiple sourcing choice instead of a single selection, in order to avoid the risk of rejection (Alec R. Levenson and Willard, 2000). The current literatures are seldom in studying various borrowers’ concerns together. Moreover, single credit source is against the reality, which borrowers are likely to apply credits from different credits. Therefore, a deep analysis is needed to answer two raised questions: what is priority ranking of borrowers’ basic concerns in borrowing credits? How much should be allocated to borrow from these three credits with considering the high importance concerns? The reminder of this study is structured as the follows: Chapter 2 reviews the current literatures about credit borrowers’ concerns. Chapter 3 introduces the methodological design of using AHP and LP. Chapter 4 discusses the contribution of AHP, and offers a numerical example to explain that how the LP model optimizes borrowing quantities. Chapter 5 conducts contributions of this study. 2. Literature Review Seldom literatures focus on studying enterprises’ consideration in their credit selection. Therefore it needs to address what components exactly involved in influencing credit selection. Due to the deficiency of one literature describes these factors; it is necessary to summarize these concerns through reviewing different literatures. The borrowers’ concerns are conducted as the follows. Interest Rate: Interest is treated as the main cost in credit borrowing. High interest rate is hardly accepted by enterprises, and they are always ready to transfer their choice to a cheaper one (Rajeev Dehejiaa et al., 2012, Ching-Chung Lin et al., 2015). The constantly seeking for lower interest rates for lenders actually aims to help themselves to reduce cost (Abhijit V. Banerjee and Duflo, 2014). Administration Fees: Matteo P. Arena and Dewally (2012) stated the administration fees spent in managing loan could not be ignored. Borrowers will invest in labours and facilities to manage their loan carefully, in order to avoid causing fault expenditure (Tennent, 2012). Transaction Cost: Borrowers sometimes need to take the transaction costs, especially in international trade (Cristina Martínez-Sola et al., 2012). It is generally caused by fluctuant exchange rates (Ġlhan Eroğlu and Eroğlu, 2012). The borrower will take the extra cost in changing the domestic currency to a foreign currency if the exchange rate increases. Openness: Openness mainly refers to the trust of borrowers to accept the request from lenders in the business history investigation. Nishant Dass and Massa (2011) evaluated borrowers’ accepance level of information openness in bank credit, which more open level means they could easier to achieve bank credit (Novita Ikasari et al., 2012). Organizational Structure: Chen Lin et al. (2011) showed that the openness of one enterprise is decided by its organizational structure. Fan et al. (2013) proved that organizations’ pyramidal structure causes low demoracy in debating the necessary of seeking for external financial help. 2 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 Human Capital: Jens M. Unger et al. (2011) found human capital influences the success of knowledge and skills- related tasks. In the process of credit selection and decision making, a knowledgeable decision maker who has capability in searching for a low interest rate credit, and better managing it by his/her professional skills (J.Huston, 2012). Business Duration: Longer business duration could better prove that one organization has a well performance in market, and also it is worthy to be invested (Paul Robsona et al., 2013). Borrowers prefer to enhance their competiveness and credibility by presenting their business durations (Karolin Kirschenmann and Norden, 2012), which would benefit their success in applying loans, and accessing competitive interest rates (Sofia A. Johan and Wu, 2014). Distance: Matteo P. Arena and Dewally (2012) described that communication is a bridge links the both sides for exchanging their consideration and aims. Far distance is believed as a barrier for communication. Robert DeYoung et al. (2008) claimed far distance easily delays in-person assessment and approval, as well as increase costs in financial institutes and enterprises. Debt-credit Relationship: Borrowers’ good history of debt-credit relationship is a guarantee of their application approval (Mingfeng Lin et al., 2013). One hand, long debt-credit relationship raises lenders’ trust for believing in borrowers’ willingness to take repayment obligation (Vuyisani Moss et al., 2013). On the other hand, the relationship lending formed by long debt-credit relationship benefits a shortcut for borrowers accessing loans and also with a negotiable interest rate (Giannetti, 2012). Approval Time: Alec R. Levenson and Willard (2000) found small firms are difficult to wait unpredictable approval time. The borrowers’ worry is the delay of their credit access which caused by long approval time. They will compare and identify one most effective approval from their selection(Srisai Chilukuri and Rao, 2014). Repayment Period: A well setting repayment period could minimize borrowers’ risk of late repayment which might causes extra interest payment (Trumbull, 2012). Flexibility payment periods reduce borrowers’ financial stresses, and a well-designed repayment time offers borrowers to raise more profit (Marc Cowling and Siepel, 2013). Lending Volume: Bo Becker and Ivashina (2014) mentioned that borrowers concern on how much credit they could access from lenders. The lending volume of financial institutions is the metric to be considered and measured by borrowers. In addition, complex procedure and unpredictable assessing period increase lenders’ uncertainty in issuing credit volumes. Credit Issued Time: Borrowers are passive for waiting their credit issued. Therefore, credit issued time significantly influences borrowers’ willingness for applying loans, and borrowers’ satisfaction is proportional to their waiting period (Doh-Shin Jeon and Lovo, 2013). On-time issued credit may help enterprises survive in budget constrained(Santiago Carbó-Valverde et al., 2012). 3 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 3. Methodology Utilizing Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is a possible way to arrange tangible and intangible factors together into a hierarchy structure. According to principle of setting criteria and sub criteria in AHP hierarchy structure (Saaty, 1990), all factors should link with the goal and aim to find the solution directly. Therefore, through reviewing current literature in previous chapter, all mentioned borrowers’ concerns could explain the relationship between borrowers’ credit selection and alternative credits. Table 1 summarizes the following metrics as the criteria in AHP. Internal Part 1. Interest Rate 2. Administration Fees 3. Transaction Cost 4. Openness 5. Organizational Structure 6. Human Capital 7. Business Duration External Part 8. Distance 9. Approval Time 10. Repayment Period 11. Lending Volume 12. Credit Issued Time 13. Debt-credit Relationship Table 1, the summary of criteria in AHP hierarchy structure Based on above listed criteria, for the criteria in internal part, it could summarize 1 to 3 as the criteria of Costs, and 4-7 as criteria of Organization’s Conditions. For the metric in external part, 1 and 6 could be categorized as the criteria of Borrowing Constraints, 2 to 5 are treated as the main criteria of Credit Requirements. These systematic criteria will be set as main criteria, and all these 13 criteria will be treated as sub-criteria. Therefore, it could set the AHP Hierarchy structure as the following Figure 1. 4 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 Figure 1, the AHP Hierarchy Structure As the description by Ordoobadi (2013) about benefits of AHP, utilizing AHP can determine a ranking of importance for the selected factors. Bases on above structure, the next step is calculating the weights of criteria and final ratings of alternative credits. 5 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 3.1 Weights of the Criteria and Alternative Credits According to the AHP theory (Saaty, 1990), the calculation of each weight should follow the sequence from top to bottom by using pairwise comparison, and their weight will be marked by a scale from 1 to 9 which are referring that importance is from lowest to highest. The principle of AHP pairwise comparison is referring that for the two options i and j, how many times i is referred to j. Therefore, it could assume that the values of i and j are wi and w wj respectively. Therefore, for the preference of option i to j is wi (Saaty, 1990). For the subj criteria, it also follows the above matrix to calculate the weights. Finally, for the weights of w each criterion, it is equal to: Weight of ith ∑n i wi, (n≤4). All weights should be measured by i 1 the consistency ratio (CR) in order to check their validity (S. H. Ghodsypour and O'Brien, 1998). A two-stage questionnaire is sent for collecting data. The data in first stage is used for measuring weights of the criteria, and the data in second stage is for evaluating ratings of alternative credits. The weights of the criteria and alternative credits are the main contribution of AHP in this study. 3.2 Set the Objective Function for Linear Programming Setting objective function is aim to link the contribution of AHP with LP. The aim of utilizing LP model is allocating optimal borrowing quantities for a credit borrower. Maximizing loans borrowing value (LBV) is objective in LP model. LBV is referring that the borrower could optimize credits borrowing volumes with lowest costs. Therefore, the objective function and constraints in the linear model are designed as follows: wi : Ratings of ith credit xi : Borrowing quantity for credit As above introduction, the objective function aims to calculate the maximum LBV, and wi denotes to the ratings of alternative credits, and xi denotes to the borrowing quantity from the th i credit. Therefore the objective function is created as: ( BV) n i 1 wi xi . For the constraints of this objective function, they should follow the result from AHP analysis, which the weight of each criterion is referring the importance of borrower’s concerns. The top importance concerns will be selected as the constraints of this function. 4. Discussion The questionnaire collected 15 companies about their marks for rating criteria. According to the data in first stage, the respondents offered their marks in evaluating the concerns. These marks are calculated through the pairwise comparison, which shows the result as following 6 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 Table 2. D1 A2 D4 D3 D2 A1 B1 B3 C2 A3 B4 C1 B2 Approval Time Administration Fees Credit Issued Time Lending Volume Repayment Period Interest Rate Openness Human Capital Debt-credit Relationship Transaction Cost Business Duration Distance Organizational Structure Table 2, the ratings of criteria 0.28466 0.19720 0.15817 0.13346 0.12885 0.09143 0.04933 0.04866 0.04180 0.04076 0.03691 0.03206 0.01243 Table 2 lists the importance of each concern in influencing borrowers’ credit selection. Based on these criteria’s importance ratings, the second stage data collection selects top 6 important criteria (D1 to A1) to rate bank credit, trade credit and 3PL credit. Therefore, with considering the criteria from D1 to A1 in Table 2, the final ratings of these three credits are listed as the following Table 3. Bank Credit Trade Credit 3PL Credit Approval Time * 0.09632 0.27958 0.62410 Administration Fees * 0.10689 0.26581 0.62731 Credit Issued Time 0.14452 0.25063 0.60485 Lending Volume 0.12203 0.22679 0.65117 Repayment Period 0.12135 0.27084 0.60781 Interest Rate * 0.08564 0.29661 0.61776 Final Rating 0.11279 0.26504 0.62217 Table 3, the final ratings of bank credit, trade credit and 3PL credit 4.1 Modelling the Borrowing Allocation by Linear Programming Table 3 offers the final ratings of alternative credits. The LP model assumes that one budget constrained company requires specific amount of capital. There are three kinds of credits which involve bank credit, trade credit and 3PL credit can be accessed. The borrower considers and compares these credits by measuring their approval time, administration fees, accurate of credit, lending volume, repayment periods and interest rate, in order to allocate the borrowing quantities from these three credits. Therefore, in this model, it could set these six concerns as the constraints of the objective function. They are formulated as follows: vi : Maximum lending volume of ith credit ti : Approval waiting period of each borrowing quantity from ith credit fi : Percent of administration cost in each borrowing quantity from ith credit 7 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 ri : Interest rate of ith credit pi : Repayment period of each borrowing quantity for ith credit (Monthly) oi : Occurrence rate of credit issued credit inaccurately in one credit period tn : Extra waiting period when lenders issued credit inaccurately C1 : Maximum acceptable rate of overall waiting cost in each borrowing C2 : Maximum acceptable rate of administration cost in each borrowing C3 : Maximum acceptable rate of interest payment in each borrowing C: Daily waiting cost of the borrower B: The overall volume of credit which the borrower needs to borrow T: Borrowing Period Bases on the above notations, the constraints are created as follows: Approval Time & Accurate of Credit: The borrower applies credit from three lenders with different waiting periods ti . ti denotes to approval waiting time of ith credit. The borrower has a daily cost for approval waiting period, which is set as C. The borrower should consider the lender’s occasional delay in issuing credits. The occurrence rate of delay is . It will increase the waiting time , and the extra waiting time is set as tn . The cost caused by overall waiting time should be less than the value of maximum acceptable overall waiting cost. It is presents as the maximum acceptable rate of overall th waiting cost times the borrowing quantities from i credit. Therefore, the constraint of approval time and accurate of credit is shown as the follows. C ti (1 oi ) oi (ti tn )C≤C1 B Administration Fees: Administration fees are spent by borrower in managing their credit. fi denotes to percent of administration cost in each borrowing quantity from credit, which is referring that the borrower should pay fi xi administration fees if it achieve xi quantity of credit from ith credit. The overall administration fees have been set as C2 . Therefore, this constraint is: n fx≤ i 1 i i C2 B Lending Volume: xi denotes to the borrowing volume of the borrower borrows from ith credit. As the assumption which maximum lending volumes of each credit is vi , this constraint is: xi ≤vi , i 1, 2, n And ni 1 xi B Repayment Period: pi is referring the repayment period of each borrowing quantity for ith credit. Repayment period is essential factor which can decide borrower’s interest payment. Therefore, this criterion should be combined with interest rate to be set as a constraint. Interest Rate: Interest rate decides the borrower’s interest payment. It normally calculated by principal repayment method, which can minimize the borrower overall interest payment (Broverman, 2010). In this method, the amount of interest for the borrower paying to the lender is presented as: 8 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 PV(1 r)n r C (1 r)n 1 PV: the credit volume which the borrower got from the lender C: Overall interest payment to the lender n: number of repayment r: Interest rate If ri denotes to the interest rate which needs to pay for the ith credit, the repayment period is pi borrowing period T, and the maximum acceptable rate of paying interest has been set as C3 . This constraint is: T n i 1 xi (1 ri )pi ri (1 ri 4.2 T )pi ≤ C3 B 1 Numerical Example of Linear Programming Model In the modelling numerical example, assuming a budget constrained manufacturer aims to maximize its LBV. It supposes that the manufacturer needs to borrow £2 million for 6 months from bank, trade and 3PL credit. The maximum acceptable administration cost takes 18% of borrowing credits, and the maximum acceptable interest payment takes 20% of borrowing credits. Specifically, the approval waiting time would cost the manufacturer £1,000/day, and the maximum acceptable rate of overall waiting cost takes 3% of borrowing credits. The details about interest rates, repayment periods and maximum lending volumes of these three credits are introduced as the following Table 4. Bank Credit Trade Credit 3PL Credit Interes t Rate (Year) Repaymen t Period (Days) 6.15% 6.00% 5.80% 90 60 30 Maximum Lending Volume (Million) Occurrence Rate of Inaccurate Credit (per Period) & Extra Waiting Time 2.5 0.010% (3) 2.1 0.015% (4) 1.9 0.013% (4) Table 4, Credits’ Information Percent of Administr ation Fees Approval Length (Days) 0.20% 0.17% 0.15% 25 20 15 Bases on the above credits’ information, and combines with the design of objective functions and constraints, it could establish an optimal allocation model through using LP technique. The model can be written as: . BV 0.11279x1 0.26504x2 0.62217x3 Overall Waiting Costs: 1,000 25 (1-0.01 ) 0.01 3 1,000≤3 x1 → x1 833,260 9 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 x2 666,586.6667 x3 499,952.3333 Administration Fees: 0.20x1 0.17x2 0.15x3 ≤360,000 Maximum Lending Volume: x1 ≤2,500,000, x2 ≤2,100,000, x3 ≤1,900,000 Interest Payment: 0.01028x1 0.01508x2 0.02935x3 ≤400,000 Through the optimization function in Excel, it could achieve the result and sensitivity check as the following Table 5 and 6. Result The Borrower Constraints Administration Fees Interest Payment Overall Borrowing Minimum Borrowing Volume Maximum Lending Volume Optimal Borrowing Schedule Bank Trade 3PL Credit Credit Credit 833,260 666,586.67 500,153.33 Sum Maximum 166,652 113,319.73 75,023 354,994.73 360,000 8,565.91 10,052.13 14,679.5 33,297.54 400,000 833,260 666,586.67 500,153.33 2,000,000 2,000,000 833,260 666,586.67 499,952.33 2,500,000 2,100,000 2,000,000 581,835.92 49 Table 5, The optimal borrowing quantities from bank, trade and 3PL credits Max LBV 10 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 Sensitivity check Constraints Name Administration Fees Sum Interest Payment Sum Overall Borrowing Sum Final Value Shadow Price Constraint R.H. Side Allowable Increase Allowable Decrease 354994.7333 0 360000 1E+30 5005.266666 33297.54007 0 400000 1E+30 366702.4599 2000000 2000000 33368.44444 201 0.62217 Table 6, Sensitivity check for optimal allocation 5. Conclusion Through the integration of AHP and LP, this article helps a budget constrained company to rate the priority of concerns in selecting credits, and also offer a solution for optimizing its borrowing quantities bases on its highly important concerns. The integration of AHP and LP can be applied into different scenarios. A new scenario can be created if LP model considers different concerns for optimizing borrowing quantities. Overall, the findings of this article have been obtained as the follows: 1. Both qualitative and quantitative concerns are measured. 2. Real data achieved through the questionnaire could reflect borrowers’ concerns in selecting credit. 3. Borrowers’ concerns are identified and rated according to their importance. The weights of concerns and final ratings of credits are calculated by pairwise comparison, which avoids the error caused by human judgement. 4. Integration of AHP and LP offers a strategy for optimizing borrowing quantities. AHP sets constraints and coefficients for LP, and LP optimizes borrowing quantities. Changing AHP criteria would transform constraints in LP model, and create another scenario. Reference ABHIJIT V. BANERJEE & DUFLO, E. 2014. "Do Firms Want to Borrow More? Testing Credit Constraints Using a Directed Lending Program". Review of Economic Studies, 81, 572-607. ALEC R. LEVENSON & WILLARD, K. L. 2000. "Do Firms Get the Financing They Want? Measuring Credit Rationing Experienced by Small Businesses in the U.S.". Small Business Economics 14, 89-94. BO BECKER & IVASHINA, V. 2014. "Cyclicality of credit supply: Firm level evidence ". Journal of Monetary Economics 62, 76-93. BROVERMAN, S. A. 2010. "Mathematics of Investment and Credit", Winsted, ACTEX Publications. CHEN LIN, YUE MA, PAUL MALATESTA & XUAN, Y. 2011. "Ownership structure and the cost of corporate borrowing". Journal of Financial Economics 100, 1-23. 11 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 CHING-CHUNG LIN, SHOU-LIN YANG & LEE, H.-I. 2015. "Bank Concentration and enterprise borrowing cost risk: Evidence from Asian markets". Asian Ecoomic and Financial Review, 5, 194-201. CHRISTINA E. BANNIER, CHRISTIAN W. HIRSCH & WIEMANN, M. 2012. "Do Credit Ratings Affect Firm Investments? The Monitoring Role of Rating Agencies". COOK, L. D. 1999. "Trade credit and bank finance: Financing small firms in Russia". Journal of Business Venturing, 14, 493-518. CRISTINA MARTÍNEZ-SOLA, PEDRO J. GARCÍA-TERUEL & MARTÍNEZ-SOLANO, P. 2012. "Trade credit policy and firm value". Accounting and Finance 53, 791-808. DOH-SHIN JEON & LOVO, S. 2013. "Credit rating industry: A helicopter tour of stylized facts and recent theories". International Journal of Industrial Organizations, 31, 643-651. EUROSYSTEM 2014. "Survey on the access to finance of small and medium-sized enterprises in the Euro area". Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank FAN, J. P. H., WONG, T. J. & ZHANG, T. 2013. "Institutions and organizational structure: The case of state-owned corporate pyramids". The Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 29, 1217-1252. GIANNETTI, C. 2012. "Relationship lending and firm innovativeness". Journal of Empirical Finance, 19, 762-781. Ġ H N EROĞ U & EROĞ U, N. 2012. " onetary transmission channels and an assessment within the framework of the 2008 global financial crisis". African Journal of Business Management, 6, 8554-8563. J.HUSTON, S. 2012. "Financial literacy and the cost of borrowing". International Journal of Consumer Studies, 36, 566-572. JENS M. UNGER, ANDREAS RAUCH, MICHAEL FRESE & ROSENBUSCH, N. 2011. "Human capital and entrepreneurial success: A meta-analytical review". Journal of Business Venturing, 26, 341-358. KAROLIN KIRSCHENMANN & NORDEN, L. 2012. "The relationship between borrower risk and loan maturity in small business lending". Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 39, 730-757. MARC COWLING & SIEPEL, J. 2013. "Public intervention in UK small firm credit markets: Value-for-money or waste of scarce resources?". Technovation 33, 265–275. MATTEO P. ARENA & DEWALLY, M. 2012. "Firm location and corporate debt". Journal of Banking and Finance, 36, 1079-1092. MINGFENG LIN, NAGPURNANAND R. PRABHALA & VISWANATHAN, S. 2013. "Judging Borrowers by the Company They Keep: Friendship Networks and Information Asymmetry in Online Peer-to-Peer Lending". Management Science 59, 17-35. NISHANT DASS & MASSA, M. 2011. "The impact of a strong bank-firm relationship on the borrowing firm". Review of Financial Studies, 24, 1204-120. NOVITA IKASARI, FEDJA HADZIC & DILLON, T. S. 2012. "Incorporating qualitative information for credit risk assessment through frequent subtree mining for XML". In: TAGARELLI, A. (ed.) "XML data mining: models, methods, and applications ". Hershey: Information Science Reference ORDOOBADI, S. M. 2013. "Application of AHP and Taguchi loss functions in evaluation of advanced manufacturing technologies". The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 67, 2593-2605. PAUL ROBSONA, CHARLES AKUETTEH, IAN STONE, PAUL WESTHEAD & WRIGHT, M. 2013. "Credit-rationing and entrepreneurial experience: Evidence from a resource deficit context". Entrepreneurship & Regional Development: An international journal, 25, 349-370. 12 Proceedings of World Business Research Conference 11 - 13 June 2015, Hotel Novotel Xin Qiao, Beijing, China, ISBN: 978-1-922069-78-8 RAJEEV DEHEJIAA, HEATHER MONTGOMERYE & JONATHAN MORDUCHA 2012. "Do interest rates matter? Credit demand in the Dhaka slums". Journal of Development Economics, 97, 437-449. ROBERT DEYOUNG, DENNIS GLENNON & NIGRO, P. 2008. "Borrower-lender Distance, credit scoring , and loan performance: Evidence from informational-opaque small business borrowers". Journal of Finance 17, 113-143. ROSENBERG, J. M. 1993. "Dictionary of Business and Management", New York, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. S. H. GHODSYPOUR & O'BRIEN, C. 1998. "A decision support system for supplier selection using an integrated analytic hierarchy process and linear programming". International Journal of Production Economics 56-57, 199-212. SAATY, T. L. 1990. "How to make a decision: The Analytic Hierarchy Process". European Journal of Operational Research, 48, 9-26. SANTIAGO CARBÓ-VALVERDE, FRANCISCO RODRÍGUEZ-FERNÁNDEZ & UDELL, G. F. 2012. "Trade credit, The financial crisis, and firm access to finance". Documento de trabajo / Fundación de las Cajas de Ahorros. SOFIA A. JOHAN & WU, Z. 2014. "Does the quality of lender-borrower relationships affect small business access to debt? Evidence from Canada and implications in China". International Review of Financial Analysis 36, 206-211. SRISAI CHILUKURI & RAO, K. S. 2014. "Effective Credit Approval and Appraisal System: Loan Review Mechanism of Commercial Banks". International Journal of Innovation Research and Development 3, 267-274. TENNENT, J. 2012. "Guide to Cash Management", Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. TRUMBULL, G. 2012. "Credit access and social welfare: the rise of consumer lending in United States and France". Politics and Society, 40, 9-34. VUYISANI MOSS, HASAN DINCER & HACIOGLU, U. 2013. "The nature of the creditordebtor relationship in South Africa". International Journal of Reseach in Business and Social Science, 2, 2147-4478. WILNER, B. S. 2000. "The exploitation of relationships in financial distress: The case of trade credit". The Journal of Finance 55, 153-178. WILSON, N. & SUMMERS, B. 2002. "Trade credit terms offered by small firms: survey evidence and empirical analysis". Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 29, 317-351. XIANGFENG CHEN & CAI, G. 2011. "Joint Logistics and Financial Services by a 3PL firm". European Journal of Operational Research, 214, 579-587. XIANGFENG CHEN & WANG, A. 2012. "Trade credit contract with limited liability in the supply chain with budget constraints". Annals of Operations Research, 196, 153-165. 13