Experimental Archaeology INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON

advertisement

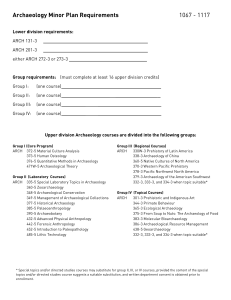

INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON Experimental Archaeology G220 2011/2012 MA-Option, 0.5 unit Co-ordinator: Dr. Ulrike Sommer E-mail: u.sommer@ucl.ac.uk Room 409a, Institute of Archaeology phone 020 7679 1493 Moodle: http://moodle.ucl.ac.uk/course/view.php?id=11165 03/02/2012 1 1. Overview Teaching schedule term 2, 2011/12 Room 410 Monday 14-16.00 Timetable Nr 1 date 09/01 lecturer Ulrike Sommer 2 3 4 5 16/01 23/01 30/01 06/02 6 7 8 9 10 20/02 27/02 05/03 12/03 19/03 Martin Schmidt Margarita Gleba Bill Sillar Chris Stevens 13-17/02 Bruce Bradley Ruth Fillery-Travis Ulrike Sommer Susanna Harris NN Ulrike Sommer subject Introduction, aims of the course The history of Experimental archaeology Experimental archaeology and experience Textiles Pottery Archaeobotany Reading Week Flint and ground Stone Experimental Archaeometallurgy Taphonomy Phenomenology Open air Museums What is missing? End-discussion Basic texts Coles, J. M. 1973. Archaeology by experiment. London, Hutchinson. INST ARCH K COL Coles, J. M. 1979. Experimental archaeology. London, Academic Press. INST ARCH AH COL and ISSUE DESK IOA COL 4 Ferguson, J. E. (ed.) 2010. Designing experimental research in archaeology: examining technology through production and use. Boulder, University Press of Colorado. INST ARCH AH FER Harding, A. F. (ed.), 1999. Experiment and design. Archaeological studies in honour of John Coles. Oxford, Oxbow. INST ARCH DA Qto HAR Section Experimental archaeology, esp. Reynolds Mathieu, J. R. (ed.) 2000. Experimental archaeology. Replicating past objects, behaviours, and processes. Oxford, BAR INT 1035, 1-12. Inst. Arch. AH Qto MAT Millson, D. C. E. 2010. Experimentation and interpretation: the use of experimental archaeology in the study of the past. Oxford, Oxbow Books. ISSUE DESK IOA MIL 9 Saraydar, St. C. 2008. Replicating the past: the art and science of the archaeological experiment. Long Grove, Waveland Press. INST ARCH AH SAR, ISSUE DESK IOA SAR Shimada, I. 2005. Experimental Archaeology. In: H. D. G. Maschner, C. Chippindale (eds.), Handbook of Archaeological methods. Lanham, Altamira Press, 603-642. IOA AH MAS World Archaeology 40/1, 2008, 1-6. INST ARCH PERS and NET 2 Periodicals -Bulletin of Primitive Technology (USA) INST ARCH PERS -Experimentelle Archäologie in Deutschland, Beihefte zur Archäologie Nordwest-Deutschlands (mainly in German) INST ARCH PERS (partly) -euroArea, Journal of (Re)Construction and Experiment in Archaeology (mainly in English) INST ARCH PERS -Lithic Technology INST ARCH PERS -Bulletin of experimental Archaeology (1980-1989) INST ARCH PERS -Bulletin of the experimental Firing Group (1982-1987) INST ARCH PERS - Forntida Teknik (Swedish), some articles online (http://www.forntidateknik.z.se/IFT/fotek.htm) useful websites -http://www.exarc.net/ www.exar.org, www.exarc.eu: European Exchange of Archaeological Research and Communication. -www.publicarchaeology.eu extensive and very useful database on experimental archaeology -http://www.palaeotechnik.de/index.html (German) - http://www.forntidateknik.z.se/ (Swedish) - VIAS (Vienna, German), http://www.univie.ac.at/vias/experimentellearchaeologie.html Teaching methods This handbook contains the basic information about the content and administration of the course. Additional subject-specific reading lists and individual session handouts may be given out at appropriate points in the course. If students have queries about the objectives, structure, content, assessment or organisation of the course, they should consult the Course Co-ordinator (Ulrike Sommer). This course will be taught by lectures with short seminars at the end of each session. The lectures will introduce the main issues and themes of the course. In a half-unit course, no full coverage of the subject is possible, the selected themes are just a narrow selection from the broad range of experimental research. Workload There will be 20 hours of lectures for this course. Students will be expected to undertake around 80 hours of reading for the course, plus 40 hours preparing for and producing the assessed work. This adds up to a total workload of some 140 hours for the course. Lecture summaries The following is an outline for the course as a whole, and identifies essential and supplementary reading relevant to each session. Information is provided as to where in the UCL library system individual readings are available; their location and status (whether out on loan) can also be accessed on the online OPAC (http://library.ucl.ac.uk/F). Readings marked with an * are considered essential to keep up with the topics covered in the course. Prerequisites There are no prerequisites for this course. 2. AIMS, OBJECTIVES AND ASSESSMENT Aims Give an overview on the development, scope and current status of experimental archaeology and discuss research frameworks and practicalities of archaeological experiments. Objectives On successful completion of this course the student should have an overview and understanding of the methods used in experimental archaeology and the difference between practical demonstrations, 3 replication and experimental archaeology. The student should be able to assess the strength and weaknesses of published experiments and plan an archaeological experiment. Knowledge and understanding: On successful completion of the course students should be able to demonstrate/have developed: • the ability to develop and implement a research project. • basic research skills in locating, understanding and discussing literature relevant to the subject of the course. • critical analysis of published works on the subject Coursework If students are unclear about the nature of an assignment, they should discuss this with the Course Co-ordinator. Students are not permitted to re-write and re-submit essays in order to try to improve their marks. The nature of the assignment and possible approaches to it will be discussed in class, in advance of the submission deadline. Please stick to the word-limit, you will be penalised for overlong submissions (for details see MA/MSc Handbooks). Word-length Strict new regulations with regard to word-length were introduced UCL-wide with effect from the 201011 session. If your work is found to be between 10% and 20% longer than the official limit you mark will be reduced by 10%, subject to a minimum mark of a minimum pass, assuming that the work merited a pass. If your work is more than 20% over-length, a mark of zero will be recorded. The following should not be included in the word-count: bibliography, appendices, tables, graphs and illustrations and their captions. Submission procedures Students are required to submit the blue form (available from the web, from outside Room 411A or at Reception) to the co-ordinator's pigeon-hole via the Red Essay Box at Reception by the appropriate deadline. I do not require a hardcopy, the turnitin-submission is sufficient! Late submission will be penalized unless permission has been granted and an Extension Request Form (ERF) completed. Please see the Coursework Guidelines document at http://www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology/handbook/common/ for further details on the required procedure. Please get in contact with me before the deadline if there are any problems! Students who encounter technical problems submitting their work to Turnitin should email the nature of the problem to ioa-turnitin@ucl.ac.uk in advance of the deadline in order that the Turnitin Advisers can notify the Course Co-ordinator that it may be appropriate to waive the late submission penalty. If there is any other unexpected crisis on the submission day, students should e-mail the Course Co-ordinator, and follow this up with a completed ERF Please see the Coursework Guidelines on the IoA website (or your Degree Handbook) for further details of penalties. UCL-WIDE PENALTIES FOR LATE SUBMISSION OF COURSEWORK -The full allocated mark should be reduced by 5 percentage points for the first working day after the deadline for the submission of the coursework or dissertation. -The mark will be reduced by a further 10 percentage points if the coursework or dissertation is submitted during the following six calendar days. -Providing the coursework is submitted before the end of the first week of term 3 for undergraduate courses or by the end of term 3 in the case of Master’s courses, but had not been submitted within seven days of the deadline for the submission of the coursework, the mark will be recorded as a minimum pass mark, provided that the work merits a pass. -Where there are extenuating circumstances that have been recognised by the Board of Examiners or its representative, these penalties will not apply until the agreed extension period has been exceeded. Please see the Coursework Guidelines on the IoA website (or your Degree Handbook) for further details of penalties. http://www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology/administration/students/handbook/submission http://www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology/administration/students/handbook/turnitin Turnitin advisers will be available to help you via email: ioa-turnitin@ucl.ac.uk if needed. 4 Be aware that turnitin tends to slow down when deadlines are approaching. If there are difficulties, you can also email the essay to me, but make sure it did actually arrive, there have been problems with UCL-email in the past. It is your responsibility to make sure the essay reaches me inside the deadline! The Turnitin-code for the course is 298174, the password is IoA1112 (Capital I, small letter o, Capital A). Further information is given at http://www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology/handbook/common/cfp.htm. Turnitin advisors will be available to help you via email: ioa-turnitin@ucl.ac.uk if you need help generating or interpreting the reports. Please submit the complete essay to turnitin, including illustrations (they will be visible to the lecturer, even if they are not visible to you!), captions, list of illustrations and bibliography. Please use wordformat, pdfs must be handed in as hard-copies as well! If you don't trust Word's handling of figures, you can submit a pdf and a Word-file (or add the pictures at the end of the file). I can also deal with Pages or Open-Office formats. The electronic submission should contain the following heading: G220, 2010/11, essay no. # your name (insert Name here !) Title of the essay/project documentation date of submission wordcount dyslexia, if applicable I download essays in a bunch, and I do not want to guess who possibly might have submitted "essay1lastVersion2.doc"!!! Keeping copies Please note that it is an Institute requirement that you retain a copy (this can be electronic) of all coursework submitted. When your marked essay is returned to you, you should return it to the marker within two weeks, unless it was marked electronically. Word-length Strict new regulations with regard to word-length were introduced UCL-wide with effect from the 201011 session. If your work is found to be between 10% and 20% longer than the official limit you mark will be reduced by 10%, subject to a minimum mark of a minimum pass, assuming that the work merited a pass. If your work is more than 20% over-length, a mark of zero will be recorded. The following should not be included in the word-count: bibliography, appendices, and tables, graphs and illustrations and their captions. Timescale for return of marked coursework to students You can expect to receive your marked work within four calendar weeks of the official submission deadline. If you do not receive your work within this period, or a written explanation from the marker, you should notify the IoA’s Academic Administrator, Judy Medrington. Citing of sources Coursework should be expressed in a student’s own words giving the exact source of any ideas, information, diagrams etc. that are taken from the work of others. Any direct quotations from the work of others must be indicated as such by being placed between inverted commas. Plagiarism is regarded as a very serious irregularity which can carry very heavy penalties. It is your responsibility to read and abide by the requirements for presentation, referencing and avoidance of plagiarism to be found in the Coursework Guidelines document at http://www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology/handbook/common/ (or in your BA/BSc Handbook) The Institute of Archaeology referencing guide can be found under http://www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology/handbook/common/referencing.htm and should be adhered to closely. If you use any other system of referencing, please state which system this is and a source your Bibliography. Bibliographies should be ordered alphabetically. Illustrations It is good practice to illustrate essays, dissertations and presentations (it can also help you to cut down on lengthy descriptions etc.). The illustrations included should be relevant to your argument, not sim5 ply nice to look at. Every illustration should be numbered and referred to by this number in the text. Guidelines on illustration are to be found at: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology/intranet/students.htm. Scanners are available in several locations. The primary location for Institute students is in the Institute's Photography Lab (Room 405), where tuitition and advice on their appropriate use is available. If you are involved in a project that requires large amounts of scanning it may be worth getting access to the scanner in the AGIS Lab (Room 322C, contact Mark Lake, Andy Bevan or the IoA computerspecialist for details of access and training on use of this scanner). There is another scanner (must be booked) at the ISD Helpdesk (http://www.ucl.ac.uk/is/helpdesk/facilities/index.htm) If there are problems, get in touch with me. Some basic knowledge of Photoshop Elements or a similar graphics program is useful here. Make sure your pictures are properly cut, not skewed and of sufficient contrast. Each illustration should be labelled (fig. 1 to #) and referred to by this number in the text. Each illustration must be provided with a source, either in the text or as a list of illustrations at the end of the essay/dissertation. You can take illustrations from the internet, but make sure they are of sufficient quality and are provided with a source. Further information More important information on submission and assessment of essays, plagiarism, the use of turn-it-in and the layout of essays can be accessed under: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology/handbook/common/index.htm which every student should consult. ASSESSMENTS This course is assessed by means of two pieces of course-work, Word-limit: 2.500. 1. Essay either of the two subjects below: 1. What would a postprocessual framework for experimental archaeology look like? 2. Critique of a published archaeological experiment This should contain: -a review of proper procedures to follow in an archaeological experiment -an assessment of the methods used in the text you chose -an assessment of the results, both in relation to archaeological research in general – did it answer a valid question, did it produce interesting results, how is it going to further future research and in relation to the methods used: -were the methods used appropriate to the research question? If not, which methods should have been used? If possible, refer to published examples where those methods have been used. -were the results of previous research incorporated? Points to keep in mind: -choosing a “perfect” experiment does not give you much scope to show your critical judgement -choosing a very bad example gives you plenty to write about, but not much opportunity to show the sophistication of your judgement. -best choose an area you are familiar with, and where you can refer to other, better studies (and methods) -think of this exercise not as a book review, but rather as assessing a grant application or a dissertation. Work out if the questions asked are useful, if the methods used are suitable, and if the results produced are useful. essential reading: Kelterborn, P. 2004. Principles of experimental research in archaeology. euroREA 2, 119-120. INST ARCH PERS and SCAN Lammers-Keijsers, Y. M. J. 2004. Scientific experiments: a possibility? Presenting a general cyclical script for experiments in archaeology. euroREA 2, 18-24. INST ARCH PERS and SCAN Millson, D. C. E. 2010. Experimentation and interpretation: the use of experimental archaeology in the study of the past. Oxford, Oxbow Books. ISSUE DESK IOA MIL 9 6 2. Essay either of the two below: 4. Outline of a one-hour lecture on an area of experimental archaeology not covered in this course. word-limit: 2000-5000 words notes: Normally, you need about 3 1/2 minutes to read a page (12 pt, New Times Roman, normal margin) without discussing any pictures. Thus, a 40 minute lecture (50 minutes + 10 minutes for questions and discussion) will fill about 15 pages, which is well above the word limit. Thus, this essay should consist of notes and bulletpoints rather than complete sentences. -Make sure the notes are comprehensible for an outsider (or for you, after a year or so) -include full references -include full references to the illustrations you want to show, but you do not need to include the actual illustrations/slides (but provide some key ones) example: slide 33, medieval siege-tower, reconstructed by the Duke of Clarence in 1858 source: Miller 1876, fig. 33 points to make: -wrong kind of wood -modern screws -too heavy to move with ease… make sure that: -there is a clear learning outcome -you have got a clear structure (use different formats of headings to make the structure clearer) -the illustrations help you to make your point -you provide sufficient information on context (where and when, and why?) remember that students listen only half the time at best! 5. An outline for a project in experimental archaeology word-limit: 2.500 words (remember, there is no lower word-limit!) Choose any area, it does not have to be covered by lectures in this Provide informations on: -the question you want to answer by conducting this experiment -the methods used -possible outcomes and their interpretation -sources of error -materials needed -observation equipment needed -timeframe This outline should make use of tables, schematic drawings lists and bullet-points where appropriate. It should include full references! Deadlines Essay 1: 20/02/2012 Essay 2: 02/04/2012 4. ONLINE RESOURCES The full UCL Institute of Archaeology coursework guidelines are given here: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology/handbook/common/marking.htm. The full text of this handbook is available here (includes clickable links to Moodle and online reading lists) http://www.ucl.ac.uk/silva/archaeology/course-info/. Online reading list available at: http://ls-tlss.ucl.ac.uk/cgi-bin/displaylist?module=# 7 Moodle The course Moodle is available under: http://moodle.ucl.ac.uk/course/view.php?id=11165 The registration key is G220 5. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION Libraries and resources In addition to the Library of the Institute of Archaeology, the other library in UCL with holdings of particular relevance to this degree is the Bloomsbury Science Library (D.M.S. Watson Library). A library outside UCL with holdings also relevant to this degree is the University of London Senate House Library (http://catalogue.ulrls.lon.ac.uk/search~S24). They have a lot of older Archaeological literature. Other libraries in London that contain archaeological books and periodicals are the British Library (http://searchbeta.bl.uk/primo_library/libweb/action/search), the Society of Antiquaries (http://www.sal.org.uk/library/catalogue/) and in some cases the SOAS library: (http://www.soas.ac.uk/library/). For other British libraries, check the COPAC (http://copac.ac.uk/). Information for intercollegiate and interdepartmental students Students enrolled in Departments outside the Institute can collect hard copies of the Institute’s coursework guidelines from Judy Medrington’s office (411). Dyslexia If you have dyslexia or any other disability, please make your lecturers aware of this. Please discuss with your lecturers whether there is any way in which they can help you. Students with dyslexia are reminded to indicate this on each piece of coursework. Feedback In trying to make this course as effective as possible, we welcome feedback from students during the course of the year. All students are asked to give their views on the course in an anonymous questionnaire which will be circulated at one of the last sessions of the course. These questionnaires are taken seriously and help the Course Co-ordinator to develop the course. The summarised responses are considered by the Institute's Staff-Student Consultative Committee, Teaching Committee, and by the Faculty Teaching Committee. If students are concerned about any aspect of this course we hope they will feel able to talk to the Course Co-ordinator, but if they feel this is not appropriate, they should consult their Personal Tutor, the MA-Tutor, the Academic Administrator (Judy Medrington), or the Chair of Teaching Committee (Dr. Mark Lake). Health and safety The Institute has a Health and Safety policy and code of practice which provides guidance on laboratory work, etc. This is revised annually and the new edition will be issued in due course. All work undertaken in the Institute is governed by these guidelines and students have a duty to be aware of them and to adhere to them at all times. • Food and drink must not be consumed during practicals • when using sharp implements, adequate protection must be used. Thighs should be covered with shirts or trousers • all tools must we used with adequate caution 8 The following is a session outline for the course as a whole, and identifies essential and supplementary readings relevant to each session. Information is provided as to where in the UCL library system individual readings are available. Their location can also be accessed on the eUCLid computer catalogue system. The recommended readings are considered essential to keep up with the topics covered in the course sessions. It is expected that students will have read these prior to the session under which they are listed. Copies of individual articles and chapters identified as essential reading are in the Teaching Collection in the Institute library (where permitted by copyright). Students are reminded that the copying of items from the teaching collection is not permitted. 9 LECTURE SUMMARIES 1. Introduction Ulrike Sommer Overview of the subject matter covered by the course, assessment, resources The development of Experimental archaeology Ulrike Sommer Summary The development of the experimental approach is closely connected with the ideology of modernity. Experiments in archaeology have been conducted from the very beginning of antiquarian research, especially in context of the discussion about spontaneous creation. Later on, experimental archaeology became connected to the empiricist paradigma of New Archaeology. How experimental archaeology fits into a post-processual framework has not yet been discussed in much detail. Essential reading Ascher. R. 1961. Experimental archaeology. American Anthropologist 63, 793-816. Ascher. R. 1961. Analogy in archaeological interpretation. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 17, 317-325. Graham. J., R. Heizer, R., Hester, T. 1972. A Bibliography of Replicative Experiments in Archaeology Ingersoll. D., Macdonald, W. K. 1977 Introduction. In: D. Ingersoll. J. E. Yellen, W. Macdonald (eds), Experimental Archaeology. New York, Columbia University Press, xi-xviii. Reynolds. P. J. 1978. Archaeology by experiment: a research tool for tomorrow. In: Darvill, T. C., M. Parker Pearson, M. Smith, R. W. S., Thomas R. M. (eds) New Approaches to our Past: An Archaeological Forum. Southampton, University of Southampton, 139-155. Schiffer, M. B., Skibo, J. M. 1987. Theory and experiment in the study of technological change. Current Anthropology 28, 595-622. Tringham, R. 1978. Experimentation, ethnoarchaeology and the leapfrogs in archaeological methodology. In: Gould, R. A. (ed.), Explorations in Ethnoarchaeology. Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press, 169-199. INST ARCH AH GOU Theory Outram, A. 2008. Introduction to experimental archaeology. World Archaeology 40/1, 1-6. ONLINE Seetah, K. 2008. Modern analogy, cultural theory and experimental replication: a merging point at the cutting edge of archaeology. World Archaeology 40, 135-150. ONLINE Wylie, A. 1985. The reaction against analogy. In: M. B. Schiffer (ed.), Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 8. New York, Academic Press, 63-111. Wylie, A. 1989. The interpretive dilemma. In: V. Pinsky, A. Wylie (eds), Critical Traditions in Contemporary Archaeology: Essays in Philosophy, History, and Socio-politics of Archaeology. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 18-27. INST ARCH AH PIN Ethnoarchaeology Hodder. I. 1982. The Present Past: An Introduction to Anthropology for Archaeologists. London, Batsford. INST ARCH BD HOD Kramer, C. 1979. Ethnoarchaeology. New York, Columbia University Press. INST ARCH AH KRA, ISSUE DESK IOA KRA Orme, B. 1974. Twentieth-century prehistorians and the idea of ethnographic parallels. Man 9, 199212. van Reybrouk, D. 2000. Beyond ethnoarchaeology? A critical history on the role of ethnographic analogy in contextual and post-processual archaeology. In: A. Gramsch (ed.), Vergleichen als archäologische Methode. Analogien in den Archäologien. BAR S 825. Oxford: Archaeopress, 39-51. INST ARCH AK Qto GRA 10 "Authenticity" Coates, J., Morrison, J. 1987. Authenticity in the replica Athenian trieres. Antiquity 61, 87-90. ICOMOS, The Nara Document on Authenticity 1994. http://www.international.icomos.org/naradoc_eng.htm see also http://whc.unesco.org/en/events/443/ History Blacking, J. 1953. Edward Simpson, alias 'Flint Jack', a Victorian Craftsman. Antiquity 27, 105-113. Paardekooper, R. P. 2008. Experimental archaeology. In Pearsall, D. M., (ed.), Encyclopedia of Archaeology. Oxford: Academic Press, 1345-1358. IOA AG PEA, ONLINE 11 2. Experimental archaeology and experience Martin Schmidt, Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum Hannover Summary Experimental Archaeology (EA) has started as an empirical method to test technical things in Archaeology, like flint knapping, making pottery, etc. The method has started in the seventeenth century when pottery was smoked and fired to prove that black pots (i.e. urns) were actually manmade by special firing techniques and not “growing” in the soil, coming up to the surface from time to time. th In the 20 Century, the method was broadened up to include taphonomic experiments. Peter Reynolds, one of the pioneers of Experimental Archaeology, has defined the range of the subject: 1. Construct: 1:1 scale constructions that test a hypothetical design for a structure (e.g. house) based upon archaeological evidence. It is a hypothesis that literally stands or falls. 2. Processes and function experiments: investigations into how things were achieved in the past. This includes investigations into what tools were for, how they were used and how other technological processes (e.g. tar rendering or pit storage) were achieved. 3. Simulation: experimental investigations into formation processes of the archaeological record and post-depositional taphonomy. 4. Eventuality trial: usually combining all three categories above, these are large-scale, often longue dure´e, experiments that can investigate complex systems (such as agriculture) and chart variations caused by unexpected or rare eventualities (e.g. extreme weather). 5. Technological innovation: where archaeological techniques themselves are trialled in realistic scenarios. A good example would be the testing of geophysical equipment over a simulated, buried archaeological site. (from Outram 2008) However, we are still lacking psychological or social experiments in Archaeology, about sex, drugs, social behaviour etc. So called “living experiments” are sometimes done, but there use is in question as modern people has far too limited experience in making a (pre)historic live. Another problem in EA are the limited technical skills of experimentators. You should be trained as a craftsperson and as an archaeologist if you want to be a good experimentator! Therefore dressing up in fancy clothes or measuring working times is scientifically useless. P. Kelterborn therefore argued that “Ergebnisorientierung geht vor Erlebnisorientierung” (The result should be more important than the experience)! A proper archaeological experiment needs careful preparation, to be conducted it in a carefully controlled and monitored way, and a objective and critical examination and publication. The concept of doing EA is taken from the Sciences. This may explain why EA had been not taken very serious (or even seen as “obscure”) by the humanities (which includes Archaeology), especially in continental Europe. E. Wind (2001) has already looked at that problem some 80 years ago. But so far, Experimental Archaeologists have not taken note if his book. There are, however, important steps before experimentation, like trying something out to get just an impression, a “feeling” for a prehistoric technique. These trials can also lead to real experiments. Nowadays the term EA has been both weakened and broadened up and includes everything from Archaeological Open Air Museums, re-enactement to hands on education (cf. Paardekooper 2009). A general problem is that most of the so-called experiments are just replications of former experiments, or, put more bluntly, the reinvention of the wheel. We don’t need any more people to build, for example, another pottery kiln or bread oven, but more people building many varieties of the same oven with some little, but well documented alterations, and test their performance. experimental archaeology Coles, J. M. 1973. Archaeology by experiment. London: Hutchinson. INST ARCH K COL Coles, J. M. 1979. Experimental archaeology. London: Academic Press. INST ARCH AH COL and ISSUE DESK IOA COL 4 Forrest, C. 2008. The nature of scientific experimentation in archaeology: experimental archaeology from the nineteenth to the mid Twentieth century. In: Cunningham, P., Heeb, J., Paarde- 12 kooper, R. (eds), Experiencing archaeology by experiment. Oxford: Oxbow, 61-68. INST ARCH AH CUN Hurcombe, L. M. 2007. Archaeological artefacts as material culture. Abingdon: Routledge. INST ARCH AH HUR Kelterborn, P. 2004. Principles of experimental research in archaeology. euroREA 2/2005, 119-120. INST ARCH PERS and SCAN *Lammers-Keijsers, Y. M. J. 2004. Scientific experiments: a possibility? Presenting a general cyclical script for experiments in archaeology. euroREA 2/2005, 18-24. INST ARCH PERS and SCAN Malina, J. 1983. Archaeology and experiment. Norwegian Archaeological Review 16/2, 69-85. IoA PERS, SCAN Mathieu, J. R. 2002. Introduction. In: J. R. Mathieu (ed.), Experimental archaeology. Replicating past objects, behaviours, and processes. BAR INT 1035. Oxford, 1-12. Inst. Arch. AH Qto MAT, SCAN Outram, A. 2008. Introduction to experimental archaeology. World Archaeology 40/1, 1-6. INST ARCH PERS and NET Paardekooper, R. P. 2008. Experimental archaeology. In Pearsall, D. M., Encyclopedia of Archaeology. Oxford: Academic Press, 1345-1358. INST ARCH AG PEA http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleListURL&_method=list&_ArticleListID= 851350983&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000010182&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid= 125795&md5=f66e8f7932c97eef0ce6dee2a361cdc6 Reynolds, P. J. 1979. Iron-age farm: the Butser experiment. London, British Museum Publications. INST ARCH DAA 160 REY Strong argument for pure research *Reynolds, P. J. 1999. The nature of experiment in archaeology. In: A. E Harding (ed.), Experiment and design; Archaeological studies in honour of John Coles. Oxford: Oxbow. INST ARCH DA Qto HAR, SCAN Saraydar, St. C. 2008. Replicating the Past. The art and science of the archaeological experiment. Long Grove: Waveland. INST ARCH AH SAR Tichy, R. 2004. Presentation of archaeology and archaeological experiment. euroREA 2/2005, 113119. INST ARCH PERS and SCAN see also Callahan, E. 1999. What is experimental archaeology? In: Westcott, D. (ed.), Primitive technology: Book of earth skills. Salt Lake City, Gibbs Smith, 4-6. Cunningham, P.; Heeb, J., Paardekooper, R. (eds) 2007. Experiencing archaeology by experiment. Oxford: Oxbow. INST ARCH AH CUN Hodder, I. 1982. Symbols in action: ethnoarchaeological studies of material culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. INST ARCH DC 1OO HOD, ISSUE DESK IOA HOD 4 Keefer, E. (ed.) 2006. Lebendige Vergangenheit. Vom archäologischen Experiment zur Zeitreise. Stuttgart: Theiss. Inst. Arch. DAD 100 KEE. Richter, P. 1991. Experimentelle Archäologie: Ziele, Methoden und Aussagemöglichkeiten. In: Fansa, M. (ed.), Experimentelle Archäologie in Deutschland. Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Nordwestdeutschland. Beiheft 6. Oldenburg: Isensee, 19-49. INST ARCH DA 100 EXP Paardekooper, R. It takes two. Publishing proceedings on experimental archaeology (Book review). http://www.exarc.net/resources/articles/it_takes_two.html Schmidt, M. 1993. Entwicklung und status quo der experimentellen Archäologie. Das Altertum 39, 922. Schmidt, M. 1995. Are dull reconstructions more scientific? In: Barrois, N. and Demarez, Léonce (eds.), Les sites de reconstitutions archéologiques. Actes du colloque d'Aubechies, 2-5 septembre 1993. Namur: Archeosite, 27-30. SCAN Seetah, K. 2008. Modern analogy, cultural theory and experimental replication: a merging point at the cutting edge of archaeology. World Archaeology 40, 135-150. INST ARCH PERS and NET Shimada, I. 2005. Experimental Archaeology. In: H. D. G. Maschner, C. Chippindale (eds.), Handbook of Archaeological methods 1, Lanham: Altamira Press, 603-642. INST ARCH AH MAS, SCAN Open-Air Museums: Ahrens, C. 1990. Wiederaufgebaute Vorzeit, archäologische Freilichtmuseen in Europa. Neumünster, Karl Wachholtz. INST ARCH MG 2 AHR 13 Boonstra, A. 1997. Twee manen lang, zestig dagen leven als in de ijzertijd. Zutphen, Walburg Pers. ON ORDER Lucas, S. A. 2008. Theme Park. London: Reaktion Books. Bartlett, ARCHITECTURE G 95.84 LUK Schmidt, M. 1995. Are dull reconstructions more scientific? In: Barrois, N., Demarez, N. (eds), Les sites de reconstitutions archéologiques. Actes du colloque d’Aubechies, 2-5. Stone, P. G., Planel, P. (eds.) 1999. The constructed past. Experimental archaeology, education and the public. One world archaeology 36. London: Routledge. Sørenson, C., 2000. Theme parks and time machines. In: P. Vergo (ed.), The new museology. London: Reaction. Tichy, R., 2004. Presentation of archaeology and archaeological experiment. euroREA 2/2005 113119. Guide to the archaeological open air museums in Europe (exarc/livearch 2009) Museums and educational acitivities http://www.exarc.net/ www.exar.org, www.exarc.eu: European Exchange of Archaeological Research and Communication. Gable, E., Hadler, R. 2004. Deep dirt: Messing up the past in Colonial Williamsburg. In: Rowan, Y., Baram, U. (eds.) Marketing heritage: archaeology and the consumption of the Past. Walnut Creek: Altamira, 166-180. INST ARCH AG ROW , SCAN Mullan, B., Marvin, G. 1992. Zoo Culture. Urbana & Chicago, Weidenfeld & Nicolson. Rentzhog, St. 2007. Open Air Museums. The history and future of a visionary idea. Jämtli: Carlssons. INST ARCH MG 2 REN, SEES Misc.XVIII.2 REN. Discussed in: On the Future of Open Air Museums. (Jamtli 2008), Fornvårderen 30. P. Stone/Ph. Planel (eds.) 1999. The constructed past. Experimental archaeology, education and the public. One World Archaeology 36. London: Routledge. NST ARCH AH STO, ISSUE DESK IOA STO 3 P. G. Stone/B. L. Molyneaux (eds), 1994. The presented past: heritage, museums and education. London, Routledge. INST ARCH M 6 STO see also Crothers, M. E. 2008. Experimental archaeology within the heritage industry: publicity and the public at West Stow Anglo-Saxon village. In Cunningham, P.; Heeb, J., Paardekooper, R. (eds) Experiencing Archaeology by Experiment. Oxford: Oxbow, 37-46. INST ARCH AH CUN Forrest, C. 2008. Linking experimental archaeology and Living History in the Heritage Industry. EuroArea 5, 33-38. INST ARCH PERS Schmidt, M. 2000. Fake! Haus und Umweltkonstruktionen in archäologischen Freilichtmuseen. In: R. Kelm (ed.) Vom Pfostenloch zum Steinzeithaus. Archäologische Forschung und Rekonstruktion jungsteinzeitlicher Haus- und Siedlungsbefunde im nordwestlichen Mitteleuropa. Heide: Förderverein AÖZA e.V, 169-176. Schmidt, M. 2001. Museumspädagogik ist keine experimentelle Archäologie. Experimentelle Archäologie und Museumspädagogik. Experimentelle Archäologie Bilanz 2001. Oldenburg: Isensee, 81-89. INST ARCH DA 100 EXP *Schmidt, M., Wunderli, M. 2008. Museum experimentell. Experimentelle Archäologie und Vermittlung. Schwalbach/Ts.: Wochenschau-Verlag. INST ARCH AH SCH www.vaee.net: Vereniging voor Archeologische Experimenten en Educatie: Many links to open air museums, professionals, suppliers. Living History and Re-enactment: Bangma, A., Rushton, St., Wüst, F. (eds) 2005. Experience, Memory, Re-enactment. Rotterdam: Piet Zwart Institute publication. Main: ART BE EXP non-archaeological! Elliot-Wright, Ph. J. C. 2000. Living History. London: Brassey's. Firstbook, P. 2001. Surviving the Iron Age. London, BBC (on the TV-Series). INST ARCH DAA 160 FIR http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/british_prehistory/ironage_intro_01.shtml see also Blomann, J. 2007. Geschichte verkaufen: Eventkultur als Arbeitsfeld. Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag. 14 Müller, K. 2008. Stone age on air. A successful "living science" programme on German television. euroREA 5, 39-44. INST ARCH PERS Schlenker, R., Bick, A. 2007. Steinzeit. Leben wie vor 5000 Jahren. Stuttgart: Theiß. Book for a TV-series Sørenson, C. 2000. Theme parks and time machines. In Vergo, P. (ed.), The new museology. London: Reaction, 60-73. INST ARCH M 6 VER Authenticity and reconstructions C. Holtorf/T. Schadla-Hall, Age as artefact: On archaeological authenticity. European Journal of Archaeology 2/2, 1999, 229-247. NET and INST ARCH PERS M.-A. Kaeser 2002. L'autonomie des représentations, ou lorsque l'imaginaire collectif s'empare des images savantes. L'exemple des stations palafittiques. In: P. Jud /G. Kaenel (eds.) Lebensbilder - Scènes de vie. Actes du colloque de Zoug, 13-14 mars 2001. Zug, Kantonales Museum für Urgeschichte/GPS, 33-40. US Larsen, K. E. (ed) 1995. Nara Conference on Authenticity. Proceedings of the Conference in Nara, Japan, 1-6 November 1994. Trondheim: Tapir. ONLINE Mainka-Mehling, A. 2008. Lebensbilder. Zur Darstellung des ur- und frühgeschichtlichen Menschen in der Archäologie. Remshalden: BAG. Molyneaux B. L. 1997. The cultural life of images: visual representation in archaeology. London: Routledge. INST ARCH AL MOL Moser, St. 1999. The dilemmas of didactic displays: Habitat dioramas, life-groups and reconstructions of the past. In: N. Merriman (ed.), Making early histories in museums. London: Leicester University Press, 95-116. INST ARCH MG 2 MER Smiles, S., Moser, St. (eds) 2005. Envisioning the past: archaeology and the image. Oxford: Blackwell. INST ARCH AH SMI 15 3. Textiles Margarita Gleba Summary Experimental archaeology has been used in textile research for a long time, in particular because understanding the techniques used for textile production requires much hands-on experience. Experimental archaeology is frequently used as an analytical tool to understand structure and the technique of textiles; to document the resource and time expenditure in textile production; to understand the function of tools; to reconstruct the processes through which textiles are preserved in different archaeological contexts. The lecture will present an overview of experimental textile archaeology, focusing on some recent case studies. Essential reading Andersson Strand, E. 2010. Experimental Textile Archaeology. In: E. Andersson Strand, M. Gleba, U. Mannering, C. Munkholt, M. Ringgaard (eds.), North European Symposium for Archaeological Textiles X. Oxford, Oxbow Books, 1-3. INST ARCH KJ Qto STR Boesken Kanold, I., Haubrichs, R. 2008. Tyrian purple dyeing: an experimental approach with fresh Murex trunculus. In: C. Alfaro, L. Karali (eds), Purpureae Vestes II, Vestidos, Textiles y Tintes: Estudios sober la produccion de bienes de consumo en la antiguidad. Valencia, University of Valencia, 253-256. INST ARCH KJ Qto ALF Grömer, K. 2005. Efficiency and technique – experiments with original spindle whorls. In: P. Bichler, K. Grömer, R. Hofmann-de Keijzer, A. Kern, H. Reschreiter (eds), Hallstatt Textiles: Technical Analysis, Scientific Investigation and Experiment on Iron Age Textiles, 107-116. BAR International Series 1351. Oxford. INST ARCH DABA Qto BIC Grömer, K. and Kern, D. 2010. Technical data and experiments on corded ware. Journal of Archaeological Science 37/12, 3136-3145 ONLINE Nørgaard, A. 2008. A Weaver’s Voice: Making Reconstructions of Danish Iron Age Textiles. In: M. Gleba, C. Munkholt, M.-L. Nosch (eds), Dressing the Past. Ancient Textiles Series 3, Oxbow Books, 43-58 INST ARCH KJ GLE Peacock, E. E. 2001. The contribution of experimental archaeology to the research of ancient textiles. In: Walton Rogers, P., Bender Jorgensen, L., Rast-Eicher, A. (eds.), The Roman Textile Industry and its Influence. A Birthday tribute to John Peter Wild. Oxford, Oxbow, 181-192. INST ARCH KJ ROG Spantidaki, S. 2008. Preliminary results of the reconstruction on Theran textiles. In: Alfaro, C., Karali, L. (eds), Purpureae Vestes II, Vestidos, Textiles y Tintes: Estudios sober la produccion de bienes de consumo en la antiguidad. Valencia, University of Valencia 43-48. INST ARCH KJ Qto ALF Experimental reports of Tools and Textiles – Texts and Contexts research programme: http://ctr.hum.ku.dk/research/tools/ 16 4. Pottery Bill Sillar Summary Pottery production is probably the area where most experiments have been conducted, most of them unrecorded and repetitive. The use and breakage of pottery has received far less attention. In this lecture, Bill is going to concentrate on cooking pots and their use characteristics. Essential reading Bronitsky, G. 1989. Ceramics and Temper: a response to Feathers. American Antiquity 54/3, 589-593. ONLINE Bronitsky G., Hamer, R. 1986. Experiments in ceramic technology: the effects of various tempering materials on impact and thermal-shock resistance. American Antiquity 51/1, 89-101. ONLINE Evershed, R. 2008. Experimental approaches to the interpretation of absorbed organic residues in archaeological ceramics. World Archaeology 40/1, 26-47. ONLINE Feathers, J. K. 1989. Effects of Temper on Strength of Ceramics: Responses to Bronitsky and Hamer American Antiquity 54/3, 579-588. ONLINE Jeffra, C. 2008. Hair and potters: an experimental look at temper. World Archaeology 40/1, 151-161. ONLINE *Pierce, C. 2005 Reverse engineering the ceramic cooking pot: costs and performance properties of plain and textured vessels. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 12, 117-157. ONLINE Schiffer, M. B. 1990. The Influence of surface Treatment of heating Effectiveness of Ceramic Vessels. Journal of Archaeological Science 17, 373-381. SCIENCE DIRECT *Schiffer, M. B., Skibo, M. 1987. Theory and experiment in the study of technological change. Current Anthropology 28/5, 595-622. JSTOR Schiffer, M. B., Skibo, J. M., Boelke, M T. C., Neupert, M. A., Aronson, M. 1994. New Perspectives on Experimental Archaeology: Surface treatments and thermal response of the clay cooking pot. American Antiquity 59/2, 197-217. JSTOR Tite, M. S., Kilkoglou, V., Vekinis, G. 2001. Review Article: Strength, toughness and thermal shock resistance of ancient ceramics, and their influence on technological choice. Archaeometry 43/3, 301-324. Young L. C., Stone, T. 1990 The Thermal Properties of textured Ceramics: An Experimental Study Journal of Field Archaeology 17, 195-203. See also Stark, M. T. 2003. Current Issues in ceramic Ethnoarchaeology. Journal of Archaeological Research 11/3, 193-242. 17 5. Archaeobotany Chris Stevens, Wessex Unit Archaeobotanical experimentation took off based on the seminal work of Gordon Hillman on cropprocessing and its remains. Since then, people have been looking at the remains of specific ways of crop processing, the preservation of plant remains, especially by charring, the evidence for food preparation and cooking, and storage. Another growing area of research are experimental fields in order to understand crop yields. Essential reading Fairbairn, A., Weiss, E. (eds.) 2009. From Foragers to Farmers; papers in honour of Gordon C. Hillman, Section Ethnobotany and experiment. Oxford, Oxbow. INST ARCH BB 5 Qto FAI http://www.homepages.ucl.ac.uk/~tcrndfu/archaeobotany.htm Dorian Fuller's homepage, lots of useful general information on archaeobotany in general, including experimental approaches Crop processing Hillman, G. C. 1973. Crop husbandry and food production: modern models for the interpretation of plant remains, Anatolian Studies 23, 241-244. ONLINE Hillman, G. C. 1981. Reconstructing Crop Husbandry Practices from Charred Remains of Crops. In: R. Mercer (ed.), Farming Practice in British Prehistory. Edinburgh: University Press, 123161. Hillman, G. C. 1984. Interpretation of archaeological plant remains: The application of ethnographic models from Turkey. In: van Zeist, W., Casparie, W. A. (eds.), Plants and Ancient Man Studies in Paleoethnobotany. Proceedings of the Sixth Symposium of the International Work Group for Palaeoethnobotany, Groningen, 30 May-3 June 1983. Rotterdam: A. A. Balkema, 1-41. INST ARCH BB 5 VAN, ISSUE DESK IOA VAN 3. Jones, G. E. M. 1984. Interpretation of archaeological plant remains: Ethnographic models from Greece. In: van Zeist, W., Casparie, W. A. (eds.), Plants and Ancient Man - Studies in Paleoethnobotany. Proceedings of the Sixth Symposium of the International Work Group for Palaeoethnobotany, Groningen, 30 May-3 June 1983. Rotterdam: A. A. Balkema, 42-61. INST ARCH BB 5 VAN, ISSUE DESK IOA VAN 3. Krauss, R. Jeute, G. 1998. Traditionelle Getreideverarbeitung in Bulgarien. Ethnoarchäologische Beobachtungen im Vergleich zu Befunden der Slawen im frühen Mittelalter zwischen Elbe und Oder. Ethnol.-Arch. Zeitschr. 39/1, 489-528. Lundström-Baudais, K., Rachoud-Schneider, A. M., Baudais, D. Poissonnier, B. 2002. Le broyage dans la chaîne de transformation du millet (Panicum miliaceum): outils, gestes et écofacts. In: H. Procopiou, R. Treuil (eds), Moudre et Broyer: Méthodes. Paris: Comité des Travaux Historiques et Scientifiques, 155-180. Murray, M. A. 2000. Cereal production and processing. In: P. T. Nicholson and I. Shaw (eds.), Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 505-536. plant preservation Boardman, S., Jones, G. E. M. 1990. Experiments on the effects of charring on cereal plant components. Journal of Archaeological Science 17/1, 1-12. ONLINE Bottema, S. 1984. The composition of modern charred seed assemblages. In: van Zeist, W., Casparie, W. A. (eds.), Plants and Ancient Man, Studies in Paleoethnobotany. Proceedings of the Sixth Symposium of the International Work Group for Palaeoethnobotany, Groningen, 30 May-3 June 1983. Rotterdam: Balkena, 207-212. INST ARCH BB 5 VAN, ISSUE DESK IOA VAN 3. Dennell, R. W. 1974. Botanical evidence for prehistoric crop processing activities. Journal of Archaeological Science 1, 275-284. ONLINE Fishkis, O., Ingwersen, J., Streck, Th. 2009. Phytolith transport in sandy sediment: Experiments and modeling. Geoderma 151, 168–178. SCIENCE DIRECT Goette, Williams, Johannessen, Hastorf 1994. Towards reconstructing ancient maize: experiments in processing and charring. Journal of Ethnobiology 14/1, 1-21. ONLINE 18 Miksicek, C. 1987. Formation Processes of the Archaeobotanical Record. Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 10, 211-247. Wilson, D. G. 1984. The carbonisation of weed seeds and their representation in macrofossil assemblages. In: van Zeist, W., Casparie, W. A. (eds.), Plants and Ancient Man, Studies in Paleoethnobotany. Proceedings of the Sixth Symposium of the International Work Group for Palaeoethnobotany, Groningen, 30 May-3 June 1983. Rotterdam: Balkena, 201-210. INST ARCH BB 5 VAN, ISSUE DESK IOA VAN 3. Storage Reynolds, P. J. 1974 Experimental Iron Age Storage Pits: an Interim Report. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 40, 118-131. Currid, J. D., Navon, A. 1989. Iron Age Pits and the Lahav (Tell Halif) Grain Storage Project. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 273, 67-78. JSTOR Fields, yields, weeds Ehrmann O., Rösch M. 2005. Experimente zum neolithischen Wald-Feldbau in Forchtenberg: Einsatz und Auswirkungen des Feuers, Erträge und Probleme des Getreidebaus. In: Landesamt für Denkmalpflege (Hrsg.), Zu den Wurzeln europäischer Kulturlandschaft - experimentelle Forschungen. Materialhefte zur Archäologie 73. Stuttgart, Theiß, 109-140. Fuller, D. Q., Stevens, C. J., McClatchie, M. in press. Routine Activities, Tertiary Refuse and Labor Organization: Social Inference from everyday Archaeobotany. In: Madella, M., Savard, M. (eds.), Ancient Plants and People. Contemporary Trends in Archaeobotany. Tucson, University of Arizona Press. Madella, M., Jones, M. K., Echlin, P., Powers-Jones, A., Moore, A. 2009. Plant water availability and analytical microscopy of phytoliths: Implications for ancient irrigation in arid zones. Quaternary International 193/1-2, 32-40. SCIENCE ONLINE Rösch, M. 1998. Anbauversuche zur (prä)historischen Landwirtschaft im Hohenloher Freilandmuseum Schwäbisch Hall-Wackershofen. In: Experimentelle Archäologie in Deutschland, Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Nordwestdeutschland, Beiheft 19, 35-44. Rösch, M., Ehrmann, O., Herrmann, L., Schulz, E., Bogenrieder, A., Goldammer, J.G., Hall, M., Page, H. & Schier, W. 2002. Zu den Wurzeln von Landnutzung und Kulturlandschaft - Sieben Jahre Anbauversuche in Hohenlohe: eine Zwischenbilanz. Fundberichte aus BadenWürttemberg 26, 21-44. INST ARCH PERS Rösch, M., Ehrmann, O., Herrmann, L., Schulz, E., Bogenrieder, A., Goldammer, J.G., Hall, M., Page, H. & Schier, W. 2002. An experimental approach to Neolithic shifting cultivation. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 11, 448-450. ONLINE Rösch, M., Ehrmann, O. Goldammer, J. G., Herrmann, L., Page, H., Schulz, E., Hall, G., Bogenrieder, A., Schier, W. 2004. Slash-and-Burn Experiments to reconstruct Late Neolithic shifting cultivation. International Forest Fire News 30, 70-74. 19 6. Flint Bruce Bradley Lecture Summary Some basic trends on a very large field… Essential reading Amick, D. S. and Mauldin, R. P. 1989. The potential of experiments in lithic technology. In: D. A. Amick, R. P. Mauldin (eds), Experiments in Lithic Technology. Oxford: BAR International Series 528, 1-14. KA 3 QTO AMI Pelegrin, J. 1991. Aspects de la deÅLmarche expérimentale en technologie lithique. In: 25 ans éme d’études technologiques en Préhistoire: bilan et perspectives (XI rencontre internationale d’Archéologie et d’Histoire d’Antibes). Juan-les-Pins: APDCA, 57–63. Pelegrin, J. 2005. Remarks about archaeological techniques and methods of knapping: elements of a cognitive approach to stone knapping. In: Roux, V., Bril, B. (eds), Stone Knapping: the necessary Conditions for a uniquely Hominin Behaviour. Oxford: Oxbow Books/McDonald Institute Monograph, 23-33. IOA ISSUE DESK; ROU KA ROU Additional Reading D. A. Amick, R. P. Mauldin (eds), Experiments in Lithic Technology. Oxford: BAR Int Ser 528, 259276. IOA KA 3 QTO AMI History of research Johnston, J. 1978. A history of flintknapping experimentation 1838-1976. Current Anthropology 19, 1978, 337-372. ONLINE Ethnoarchaeology Runnels, C. 1982. Flaked-Stone Artifacts in Greece during the Historical Period. Journal of Field Archaeology 9/3, 1982, 363-373. Whittaker, J. C. 2001. ‘The Oldest British Industry’: continuity and obsolescence in a flintknapper’s sample set. Antiquity 75, 382-390. ONLINE Tool-use/function Braun, D. R., Pobiner, B. L., Thompson, J. C. 2008. An experimental investigation of cut mark production and stone tool attrition. Journal of Archaeological Science 35, 1216-1223. ONLINE Machin, A. J., Hosfield, R. T., Mithen, S. J. 2007. Why are some handaxes symmetrical? Testing the influence of handaxe morphology on butchery effectiveness. Journal of Archaeological Science 34, 883-893. ONLINE Toth, N. 1987. Behavioral inferences from Early Stone Age artifact assemblages: an experimental model. Journal of Human Evolution 16, 763-787. ONLINE Toth, N. 1991. The importance of experimental replicative and functional studies in Palaeolithic archaeology. In: G. D. Clark (ed.), Cultural Beginnings: Approaches to understanding early hominid life-ways in the African. Bonn, Habelt, 109-124. IOA TC 3266; DC 100 CLA Toth, N., Schick, K. 2009. The Importance of Actualistic Studies in Early Stone Age Research. In: K. Schick and N. Toth (eds.), The Cutting Edge: New Approaches to the Archaeology of Human Origins. Gosport: Stone Age Institute Press. Organisation of production Boeda, E., Pelegrin, J. 1985. Approche expérimentale des amas de Marsangy. In: Les amas lithiques de la zone N19 du gisement magdalénien de Marsangy: approche méthodologique par 20 l’expérimentation. Beaune: Association pour la Promotion de l’Archéologie en Bourgogne, 19–36. Boeda, E., Pelegrin, J., Croisset, E. 1985. Réflexion méthodologique à partir de l’étude de quelques remontages. In: Les amas lithiques de la zone N19 du gisement magdalénien de Marsangy: approche méthodologique par l’expérimentation. Beaune: Association pour la Promotion de l’Archéologie en Bourgogne, 37–64. Replication Aubry, T., Bradley, B., Almeida, M., Walter, B., Neves, M.J., Pelegrin, J. Lenoir, M. Tiffagom, M. 2008. Solutrean laurel leaf production at Maîtreaux: an experimental approach guided by techno-economic analysis. World Archaeology 40/1, 48-66. ONLINE Bradley, B., Sampson, C. G. 1986. Analysis by replication of two Acheulian artefact assemblages. In: Bailey, G. N., Callow, P. (eds), Stone Age Prehistory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. BC 100 BAI Edwards, S. 2001. A modern knapper's assessment of the technical skills of the Late Acheulean biface workers at Kalambo Falls. In: J. D. Clark (ed.), Kalambo Falls prehistoric site, volume III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 605-11. IOA DCD CLA Callahan, E. 1979. The basics of biface knapping in the Eastern Fluted Point Tradition: A manual for flintknappers and lithic analysts. Archaeology of Eastern North America 7, 1-172. IOA Stores. Kelterborn, P. 1984. Towards replicating Egyptian predynastic flint knives. Journal of Archaeological Science 11/6, 433-453. ONLINE Newcomer, M. H. 1971. Some quantitative experiments in handaxe manufacture. World Archaeology 3/1, 85-104. ONLINE *Whittaker, J. C. 1994. Flintknapping: Making and Understanding Stone tools. Austin, University of Texas Press. IOA ISSUE DESK; KA WHI general introduction to flintknapping Percussion Dibble, Harold L., Pelcin, A. 1995. The effect of hammer mass and velocity on flake mass. Journal of Archaeological Science 22, 429-39. ONLINE Pelcin, A. 1997. The effect of core surface morphology on flake attributes: evidence from a controlled experiment" Journal of Archaeological Science 24:749-756. Pelcin, A. 1997. The effect of indentor type on flake attributes: evidence from a controlled experiment. Journal of Archaeological Science 24:613-621. Pelcin, A. 1997. The formation of flakes: the role of platform thickness and exterior platform angle in the production of flake initiations and terminations. Journal of Archaeological Science 24, 1107-1113. Pelcin, A. 1998. The threshold effect of platform width: a reply to Davis and Shea. Journal of Archaeological Science 25, 615-620. Learning Processes/skill Ferguson, J. R. 2008. The when, where, and how of novices in craft production. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 15, 51-67. ONLINE Finlay, N. 2008. Blank concerns: issues of skill and consistency in the replication of Scottish later Mesolithic blades. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 15, 68-90. ONLINE Roux, V., Bril, B., Dietrich, G. 1995. Skills and learning difficulties involved in stone knapping. World Archaeology 27, 63-87. Axes Mathieu. J. R., Meyer, D. A. 1997. Comparing axe heads of stone, bronze, and steel: studies in experimental archaeology. Journal of Field Archaeology 24, 333-351. ONLINE Saraydar. S., Shimada, I. 1971. A quantitative comparison of efficiency between a stone axe and a steel axe. American Antiquity 36, 216-217. ONLINE 21 Querns Adams, J. L. 1989. Methods for improving ground stone artifact analysis: Experiments in mano wear patterns. In: Amick, D. A., Mauldin, R. P. (eds), Experiments in Lithic Technology. Oxford: BAR Int. Ser 528, 259-276. IOA KA 3 QTO AMI 22 7. Experimental archaeometallurgy Ruth Fillery-Travis Lecture Summary Archaeometallurgy is concerned with understanding the production and manipulation of metals in the past, in particular establishing the processes and materials used, the effects on the surrounding environment and human motivations and experiences. Experimental archaeometallurgy is a complementary approach that can be broadly divided into three forms: • scientific experimental work where the experimenter attempts to verify an archaeometallurgical hypothesis concerning a physical or chemical process; • experiential work where the experimenter is concerned with the subjective experience of the activity, interpretation of the physical and psychological environment and activity, and the acquisition of craft skills associated with the process; • replica, re-enactment and interpretation work where the experimenter attempts to recreate an object or process for a public event, museum display, often with a focus on appearance and theatricality. In this lecture we will look at the evolution of experimental archaeometallurgy, its current theoretical basis, and discuss the types of information that can be generated through experiment. We will also discuss the limitations of experimental archaeometallurgy, a number of the current debates in the discipline, and the direction of the discipline. We will examine examples from some of the major foci in the discipline, which in the past have included: • understanding the parameters of smelting; • establishing the quantity of iron lost between the resulting iron bloom and the finished sword or tool; • replicating the casting of bronze and other copper alloys; • establishing the practical use of the cementation process for producing brass; • recreating the cuppelation process to examine past silver purification and assaying techniques. Examples are drawn mainly from Europe and are influenced by the scientific context of archaeometallurgical enquiry. Essential Reading A familiarity with the basics of archaeometallurgy will be of considerable benefit to students. Although out of print, the following remains a great introduction: Craddock, P.T., 1995. Early metal mining and production, Edinburgh University Press. In particular chapter 1. 3hr loan as ISSUE DESK IOA CRA 6, or 1 week loan as INST ARCH KE CRA be aware that this is an extremely popular book! Although now outdated, the following reference also gives a good general outline of the development of metal use in the past and archaeometallurgical approaches: Lambert, J. B. 1997. Metals. In: Lambert, J. B., Traces of the past: unravelling the secrets of archaeology through chemistry, Perseus, 168-213 http://ls-tlss.ucl.ac.uk/course-materials/ARCLG108_45766.pdf Specific reading The following reading focuses on experiments associated with iron smelting and smithing, and illustrates the wide variety of approaches, motivations and methodologies in use. As with much experimental work these references should be approached critically, with consideration given to the work’s context, limitations and evidential value to you as a researcher. • Traditional archaeological science: 23 Crew, P. 1991. The experimental production of prehistoric bar iron. Historical Metallurgy 25/2, 21-36. http://ls-tlss.ucl.ac.uk/course-materials/ARCLG108_44150.pdf • The experienced smiths’ perspective: Sauder, L., Williams, S. 2002. A Practical Treatise on the Smelting and Smithing of Bloomery Iron. Historical Metallurgy 36/2, 122-131. • An enthusiastic re-enactment and smith’s work: http://www.warehamforge.ca/ironsmelting/index.html This set of pages contains information on 45 smelts undertaken by Darrell Markewitz, an artisan blacksmith, and the DARC re-enactment group. Links to formal publications, individual smelt data and numerous videos and photos are included. • ‘Practical’ archaeology as a teaching aide and theatre: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KP4DjM3jBsw • Smelt 2010 : An archaeological and experiential approach: This multi-disciplinary project involved numerous experiments encompassing the full chaineoperatoire of iron smelting. Whilst some of the earlier experiments in this area were preoccupied with the study of the smelting furnace, this project attempted to undertake a wide variety of activities from the full chaine-operatoire of iron smelting. Brian Dolan, one of the co-organisers, documented the project through a blog, which can be accessed here: http://www.seandalaiocht.com/1/category/smelt%202010/1.html It contains a number of posts, many photographs and films of the processes. Some general background information on iron smelting can be found in the Naked Archaeology podcast on Technology (http://nakeddiscovery.com/scripts/mp3s/audio/Naked_Archaeology_09.05.17.mp3), which also includes an interesting discussion by Gerry Macdonald on cast iron and Colin Renfrew on the development of technology. Futher archaeometallurgy reading Students wishing to explore archaeometallurgy further may wish to investigate the reading lists for the archaeometallurgy units taught by Dr Marcos Martinón-Torres. These include the undergraduate ARCL3001: Archaeometallurgy unit which can be found here: http://ls-tlss.ucl.ac.uk/cgi-bin/displaylist?module=07ARCL3001 and the ARCLG108: Archaeometallurgy 1: Mining and extractive technology unit for graduate students available here: http://ls-tlss.ucl.ac.uk/cgi-bin/displaylist?module=10ARCLG108 24 8. Taphonomy Ulrike Sommer Lecture Summary The decay of structures as a clue to time depth was an early research interest. Martin Bell puts the beginning of earthwork studies with Charles Darwin's interest in earthworms from the 1835 onwards. In the 1960s, big experimental earthworks were built and are still being excavated. In recent years, there has been a burgeoning interest in burnt structures. Other fields of archaeology, as archaeobotany and especially zooarchaeology have established more or less independent frameworks of experimental and actualistic work. General Binford, L. R. 1981. Behavioral archaeology and the "Pompeii premise". Journal of Anthropological Research 37/3, 1981, 195-208 (esp. 195-202) ONLINE Cameron, C. M. 2006. Ethnoarchaeology and contextual studies. In: Papaconstantinou, D. (ed.), Deconstructing context. A critical approach to archaeological practice. Oxford, Oxbow 2006, 22-33. good overview of the literature, development of the study of formation processes. Schiffer, M B. 1987. Formation processes of the archaeological record. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1-23. general introduction Sommer, U. 1990. Dirt theory, or archaeological sites seen as rubbish heaps. Journal of theoretical Archaeology 1: 47-60. Some basic concepts Earthworks Bell. M., Fowler, P., Hillson, S. W. (eds) 1996. The Experimental Earthwork Project. 1960-1992. York, Council for British Archaeology. Crabtree K. 1990. Experimental earthworks in the United Kingdom. In: Robinson, D. E. (ed), Experimentation and Reconstruction in Environmental Archaeology. Oxford, Oxbow, 225-235. Evans, I. G., Limbrey, S. 1974. The experimental earthwork on Morden Bog, Wareham, Dorset. England: 1963 to 1972. Proceeding of the Prehistoric Society 40/1, 70-202. Jewel, P. A. (ed.) 1963. The Experimental Earthwork on Overton Down, Wiltshire. An account of the Construction of an Earthwork to investigale the Way in which Archaeological Structures are denuded and Buried. London, British Association for the Advancement of Science. Jewell, P. A., Dimbleby, G. W. 1966. The experimental earthwork on Overtown Down, Wiltshire, England: the first four years. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 32, 313-342. Settlements/Houses Cameron, C. M., Tomka, St. A. T (eds) 1993. Abandonment of settlements and regions. Ethnoarchaological and archaeological approaches. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. O'Connell, J. F. 1987. Alywara site structure and its archaeological implications. American Anthropology 52: 74-108. Schick, K. D. 1987. Modelling the formation of Early Stone Age Artifact concentrations. Journal of Human Evolution 16, 789-806. ONLINE Stevanovic, M. 1997. The Age of Clay: The Social Dynamics of House Destruction. Journal of anthropological Archaeology 16, 334–395. Discard Mainly Ethnoarchaeological, and some archaeological examples: should clarify principle issues. Hayden, B., Cannon, A. 1983. Where the garbage goes: refuse disposal in the Mayan highlands. Journal of anthropological archaeology 2:117-163. Hodder, I. 1987. The meaning of discard: ash and domestic space in Baringo. In Kent, S., (ed.), Method and Theory for Activity Area Research: an Ethnoarchaeological Perspective. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 424-448. 25 Needham, St., Spence, T. 1996. Refuse and disposal at Area 16, East Runnymede. London: British Museum. Martin, L., Russell, N. 2000. Trashing rubbish. In: Hodder, I. (ed.), Towards reflexive method in archaeology: the example at Çatalhöyük. Cambridge, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2000, 57-69. Meskell, L., Nakamura, C., King, R., Farid Sh. 2008. Figured Lifeworlds and depositional Practices at Çatalhöyük. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 18/1, 139–161. Varien, M. D., Potter, J. M. 1997. Unpacking the Discard Equation: Simulating the Accumulation of Artifacts in the Archaeological Record. American Antiquity 62/2, 194-213. Wilson, D. C. 1994. Identification and assessment of secondary refuse aggregates. Journal of archaeological method and theory 1: 41-68. Marshall, F. 1994. Food sharing and body part representation in Okiek faunal assemblages. Journal of Archaeological Science 21: 65-77. Noe-Nygaard, N. 1986. Taphonomy in archaeology with special emphasis on man as a biasing factor. Journal of Danish Archaeology 6, 7-52. see also Sommer, U. 1991. Zur Entstehung archäologischer Fundvergesellschaftungen. Versuch einer archäologischen Taphonomie. Universitätsforschungen zur prähistorischen Archäologie 6. Bonn, Habelt. STORES extensive bibliography 26 9. Phenomenology Susanna Harris Lecture Summary On the rare occasions we encounter prehistoric cloth, the preserved remains are usually fragmentary and decayed, therefore no longer retaining their original properties. However, the chemical, physical, aesthetic and sensual properties (colour, smell, flexibility and texture) of cloth are integral to the understanding of these artefacts as part of past human engagement. In this instance, experimental archaeology is a useful analytical technique for producing cloth types in the materials and techniques used in the past which can then be used to investigate their material properties and sensory perception. This lecture will look at a handling experiment that was devised as one of several analytical techniques used to investigate the material properties and sensory perception of cloth types known from the Neolithic, Copper Age and Bronze Age in the Alpine region of Europe. These include cloth made from flax, wool, tree bast, animal skins, fur, woven, twined cloth, and knotless netting. Topics will include the aims and objectives of the experiment, theoretical and methodological basis, setting up the experiment, the pilot project, continuity in collecting results, problems and benefits. As experimental archaeology is often concerned with process and function, this experiment is an example of a less-explored area of research. The lecture will be followed by a discussion of this and other potential areas that are currently missing from experimental archaeology. * marks key readings for this lecture References Edwards, E., Gosden, C., & Phillips, R. B. 2006. Introduction. In: E. Edwards, C. Gosden, & R. B. Phillips (eds), Sensible objects: colonialism, museums, and material culture. Berg, Oxford, 131. (Also look at other chapters) *Hamilton, S., Whitehouse, R. 2006. Phenomenology in practice: towards a methodology for a 'subjective' approach. European Journal of Archaeology 9/1, 31-71. Hamilton, S., Whitehouse, R. 2006. Three senses of dwelling: beginnings to socialise the Neolithic ditched villages of the Tavoliere, Southast Italy. Journal of Iberian Archaeology 8, 159184. Hansen, C. 2008, Experiment and Experience - Practice in a Collaborative Environment. In: P. Cunningham, J. Heeb, R. Paardekooper (eds.), Experiencing Archaeology by Experiment: Proceedings of the Experimental Archaeology Conference, Exeter 2007. Oxbow Books, Oxford, 69-80. INST ARCH AH CUN *Harris, S. 2008. Exploring the Materiality of Prehistoric Cloth-types. In: P. Cunningham, J. Heeb, R. Paardekooper (eds.), Experiencing Archaeology by Experiment: Proceedings of the Experimental Archaeology Conference, Exeter 2007. Oxbow Books, Oxford, 81-102. INST ARCH AH CUN Harris, S. 2009. Smooth and Cool, or Warm and Soft; Investigating the Properties of Cloth in Prehistory. In: E. Andersson Strand et al. (eds.), North European Symposium for Archaeological Textiles X, vol. 5. Oxford, Oxbow Books, 104-112. *Hurcombe, L. 2007. A sense of materials and sensory perception in concepts of materiality. World Archaeology 39/4, 532-545. ONLINE Ingold, T. 2000. Making Culture and Weaving the World. In: P. Graves-Brown (ed.), Matter, Materiality and Modern Culture. London & New York, 50-71. ANTHROPOLOGY C 9 GRA Keates, S. 2002. The Flashing Blade: Copper. Colour and Luminosity in Northern Italian Copper Age Society. In: A. Jones, G. MacGregor (eds), Colouring the Past: The Significance of Colour in Archaeological Research. Berg, Oxford, 109-125. INST ARCH KN JON Marsh, E. J., Ferguson, J. R. 2010. Introduction. In: J. R. Ferguson (ed.) Designing experimental research in archaeology: examining technology through production and use. Boulder, University Press of Colorado, 1-12. (Also look at other chapters). Merleau-Ponty, M. 1989. Phenomenology of perception (translated from the French by Colin Smith). London, Routledge. MAIN PHILOSOPHY J 119 MER Thomas, J. 2006. Phenomenology and Material Culture. In: C. Tilley et al. (eds.), Handbook of Material Culture. Sage, London, 43-59. 27 Tilley, C. 1994. A phenomenology of landscape: places, paths, and monuments. Berg, Oxford. INST ARCH BD TIL Young, D. 2006. The Colours of Things. In: C. Tilley et al. (eds), Handbook of Material Culture. London, Sage, 173-185. INST ARCH AH TIL See also Watson, A., Keating, D. 1999 Architecture and sound: an acoustic analysis of megalithic monuments in prehistoric Britain. Antiquity 73, 325-336. ONLINE 28 10. Open Air museums NN www.exarc.net Summary In this paper, experimental archaeology will be discussed from an international perspective. At first, the differences between experiment, experience and demonstration – all important keywords for the experimenter – will be explained. Examples will be given to show that building an ancient house, ship or making an ancient costume itself is no experiment, it depends on your approach to your activity. Experimental archaeology is not only a technical approach a nature science, but as well a human science. Archaeological Open Air museums pretend to be experimental, but their link with science is not through experiment, but through the subject archaeology. Following on that, a presentation will be given on who is doing experimental archaeology where and how: at universities, in Archaeological Open Air museums, in national associations / clubs, on the internet (Facebook). Finally, NN will make clear why we need cooperation, preferably worldwide. Experimenting in archaeology is one single method from a wider toolkit of methods to better understand archaeological data. Experimental archaeology is by nature interdisciplinary: it connects different professions and it connects archaeology and the public. A good international structure could guarantee good and easy contacts, also for beginners to find their way, basic ethics about good experimenting, best practises sharing and making handbooks. EXARC is a place to turn to: 1 A place for beginners to turn to: documentation & strategies 2 For more experienced: a far friend is just as valuable as a good neighbour 3 An international network, promoting good experimental archaeology There is experimental archaeology everywhere, but we need to know each other. Essential reading Essential reading Blockley, M. 2000. The social context for archaeological reconstruction in England, Germany and Scandinavia. Archaeologia Polona 38, 43-68. Comis, L. 2010. Experimental Archaeology: methodology and new perspectives in Archaeological Open Air Museums. euroREA. Journal for (Re)construction and Experiment in Archaeology 7/2010, 9-12. Schmidt, M. 1995. Are dull reconstructions more scientific? In: Barrois, N. and Demarez, Léonce (eds.), Les sites de reconstitutions archéologiques. Actes du colloque d'Aubechies, 2-5 septembre 1993. Namur: Archeosite, 27-30. SCAN Visit www.publicarchaeology.eu and read some presentations of any of the 275 archaeological open air museums listed. See also Petersson, B. 2003. Föreställningar om det förflutna, arkeologi och rekonstruktion (PhD-Thesis Lund: University of Lund. (English Summary available as word file) Bay, J. 2004. Educational Introduction to the historical workshops in Denmark, EuroREA, (Re)construction and Experiment in Archaeology 1/2004, 129-134. INST ARCH PERS Colomer, L. 2002. Educational facilities in archaeological reconstructions: Is an image worth more than a thousand words? Public Archaeology 2/2, 85-94. INST ARCH PERS Dixon, N. T. 2005. Underwater archaeology and reconstruction of a prehistoric Crannog in Loch Tay, Scotland. Experimentelle Archäologie in Europa, Bilanz 2004, Oldenburg: Museum für Natur und Mensch, 167-179. Goodacre, B., Baldwin, G. 2002. Living the Past: Reconstruction, Recreation, Re-enactment and Education at Museums and Historical Sites. London: Middlesex University Press. Hansen, H.-O., 1986. The usefulness of a permanent experimental centre? Sailing into the past. Roskilde, 18-25. Leon, W., Piatt, M. 1989. Living History Museums. In: Leon, W., Rosenzweig, R. (eds.), History Museums in the United States: a critical Assessment. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 6497. IN CATALOGUING 29 Masreira i Esquerra, C., 2007. Presenting archaeological heritage to the public: ruins versus reconstructions, EuroREA, (Re)construction and Experiment in Archaeology, 4/2007, 41-46. Mills, N. 1999. From archaeological sites to the creation of thematic museums and parks. An overview from Britain. In: Musei e Parchi archeologici. IX ciclo di lezioni sulla ricerca applicata in Archeologia, Certosa di Pontignano (Sienna) 15-21 dicembre 1997, Firenze: Edizioni All’Insegna Del Giglio, 297-311. Paardekooper, R. P., 2006. Sensing History, Interview with Hans-Ole Hansen (DK). EuroREA. Journal for (Re)construction and Experiment in Archaeology. Hradec Králové: DAEA & EXARC, Volume 3/2006, 91-95. Rasmussen, M., Grønnow, B. 1999. The Historical-Archaeological Experimental Centre at Lejre, Denmark: 30 years of experimenting with the past. In: Planel, P., Stone, P. (eds.), The Constructed Past, experimental archaeology, education and the public. One world archaeology 36. London: Routledge, 136-144. What is missing? Ulrike Sommer 30