Environmental issues Chapter 24

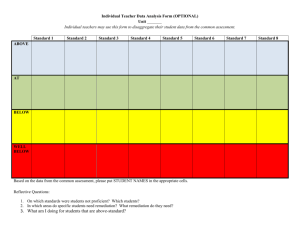

advertisement