AE U R Public Opinion on Freshwater

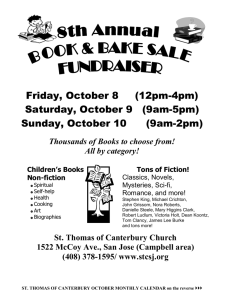

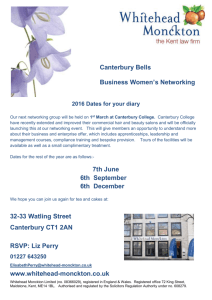

advertisement