Proceedings of Annual Spain Business Research Conference

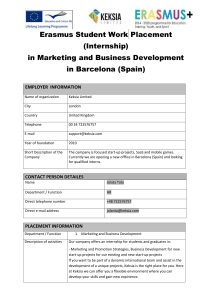

advertisement

Proceedings of Annual Spain Business Research Conference 14 - 15 September 2015, Novotel Barcelona City Hotel, Barcelona, Spain ISBN: 978-1-922069-84-9 Succession as Career Choice – Females´ Motivation to Join a Family Firm: An Explorative Study Anna Akhmedova* One important issue without solution is the fact that daughters of founders are often underrepresented in family firms. Previous research cites primogeniture, daughter invisibility and role incongruity among possible explanations. However, more recent studies suggest that such “barriers to leadership” cannot statistically explain existing gap. Most of researchers fail to take into account the changing social reality and different career opportunities available to family business daughters. Then in-depth interviews were conducted with daughters from medium-large family businesses in Spain. The study showed that mix of intrinsic and transcendent (prosocial) motives guides the career choice of family business daughters. The study empirically supports the recent stream of research that reveals that social change in gender relations and gender stereotyping is becoming a less important issue when career decisions are made. Field: Management Keywords: gender, succession, family firms, career motivation 1. Introduction The family business is one important form of business ownership that has recently become a separate field of research. The interest of academics and practitioners is motivated by the role that the family business plays in the economy of countries. Depending on definition and country the economic contribution of the family business is estimated around 12-50% of national GDP and 15-60% of workforce (i.e. Shanker, Astrahan, 1996). Further, familycontrolled businesses are often market leaders, showing more stable earnings and more sustainable practices (EFB, 2012), (Simon, 2009), (McConaughy, 1994). In Spain, Family businesses generate approximately 16 % of GDP (26% if calculated with affiliations) (IEF, 2009). Despite seeming attractiveness to women, family firms often fail to bring females to high-level positions – thus loosing valuable human capital in face of family business daughters: their professional networks, leadership potential and descendants (Eagly, 2003), (Sharma, 2004). In family business research, most findings on gender gap were made in 80s and 90s. At that time the problem was attributed to social stereotyping at early adolescence, primogeniture, “invisibility” of women and incongruity between a leader role and a gender role (or family role) (Dumas, 1989), (Eagly, 1990, 2003), (Hollander, 1990), (Marshack, 1994). However, with growing participation of females in public sphere and growing amount of data available, such ¨barriers to leadership¨ do not statistically explain the gender gap, that still * PhD student, UIC (The International University of Catalonia), Carrer Inmaculada, 22, 08017, Barcelona Annahm12@gmail.com Proceedings of Annual Spain Business Research Conference 14 - 15 September 2015, Novotel Barcelona City Hotel, Barcelona, Spain ISBN: 978-1-922069-84-9 exists. One good example, that empirically confirms this statement is a recent study of Spanish companies (Pascual Garcia, 2012). The absence of motivation of next generation is a critical point that results in an absence of suitable successors (Ward, 1997). Effectively, researchers often fail to take into account that female professionals with a family business background have diverse career options and succession is only one of them. Thus, daughters might be attracted to pursue entrepreneurial or external management career. Specifically entrepreneurship can be a lucrative option for those with family business background (Zellweger, 2011). According to Stavrou and Wislow (1996) 66% of US alumni with family business background did not want to unite with their family businesses. In EU 75% of men and 50% of women expressed low probability (under 50%) that they would join their family businesses. The majority of respondents who expressed low interest in continuing the family business showed entrepreneurial intentions. Similar results show other research (Bjuggren, Sund, 2001), (Stavrou, 1996), (Stavrou, 1999), (Stavrou et al., 2008), (Ceja, Tapies, 2009). 2. Literature review 2.1. Succession as Career Option The original work of Handler, W., (1989), draws attention of academics to three general directions in ¨next generation perspective in family firm¨: (1) desirable successor attributes, (2) performance enhancing factors, and (3) reasons these family members decide to pursue a career in their family firms. Research dedicated to the third stream usually takes a form of descriptive frameworks with typologies (Stavrou, E., 1998), (Miller, D., 2003), (Sharma, P. and Irving, P., 2005), (Lambrecht, J. and Donckels, R., 2008). Stavrou elaborates a framework of four general factors that affect next´ generation decision to join family firm (business, market, personal and family). Sharma, P. and Irving, P. (2005) provide collectively exhaustive and mutually exclusive model of reasons to join the family firm based on the types of commitment. Finally, Miller, D., (2003) provides a typology of father-son relations claiming that every type has predictable consequences of succession. Researchers seem to coincide that behavioral and performance variations can be observed depending on the type of motivation of a successor. Successor acting from a sense of obligation would be less involved, creative and willing to receive tacit knowledge of the founder compared to one intrinsically motivated. However, it was also evidenced that motivation tends to change with the time, thus a sense of obligation might later change into intrinsic involvement (OttenPapas, D., 2013). Motivation theories also confirm this fact (i.e. Ryan and Deci, 2000). Daughter perspective on succession often constructs factors that affect negatively daughter´s motivation and willingness to search for opportunities within family business (Overbeke, K. et al. 2013), (Iannarelli 1992). There is Proceedings of Annual Spain Business Research Conference 14 - 15 September 2015, Novotel Barcelona City Hotel, Barcelona, Spain ISBN: 978-1-922069-84-9 some evidence that daughters are motivated slightly differently than sons. Stavrou et al. (2008) revises motivation of US and Greek offspring and finds that there are cultural and gender differences. Finally, most of researchers tend to coincide citing the theme of disruptive event as a starting point to consider leadership in family firm is repeated across studies (Wang, C., 2010), (Overbeke, K. et al. 2013), (Dumas, C., 1989). Further, early involvement to business reinforces willingness and commitment of next generation. 2.2. Career and Career Success A modern view of career construct is the ¨unfolding sequence of a person´s work experience over time¨ (Arthur, et al, 2005), (Arthur, Hall, & Lawrence, 1989). It is worth noting, that this definition does not constrain the reader to the so-called ¨traditional¨ upward mobility within an organization, allowing free mobility across organizations, roles, occupations, countries. Hall, et al (1996) argues that the way person understands ¨career¨ and ¨career development¨ has changed over time. The shift occurred from ¨external career¨ (the actual jobs or positions that a person holds over time) to ¨internal career¨ (personal learning from work-related experiences). Thus, Hall calls a ¨protean career¨ a process, which a person, not organization, is managing searching for freedom and self-fulfillment at any stage of the life. Given a greater variety of career paths that exist today, career success becomes a less objective and somewhat more subjective issue. Subjective– objective career duality has been a traditional concern of those who have studied the trade-offs between work and family or work and leisure activities (Arthur, et al, 2005). The objective-subjective tend to correlate (i.e. a person who earns aboveaverage income and is promoted fast, will be more satisfied with his career); however, the two are conceptually different (Ng et al., 2005). Thus, regardless of salary, individuals might see themselves as successful, relying more on how satisfied they are in their job (Judge et al., 1999). Logically, the role of motivation on-the-job comes to question. According to Hall (1996), the psychological success – is what unites the objective-subjective career success dichotomy. He argues that for most individuals work is important part of their life and self and they derive deep intrinsic satisfaction from it. In general work has many of the qualities of the game – unless it becomes too demanding, interfering with other roles. Applying the research from career and career success to the case of family business daughters, we should look for specific forms of motivation or, possibly, specific bundles of motives, that are important for successors, specifically, for female successors. 2.3. Motivation Theories The research is based on humanistic theories of motivation. This stream of thought originates in findings of Mayo, research of Maslow, Herzberg and Proceedings of Annual Spain Business Research Conference 14 - 15 September 2015, Novotel Barcelona City Hotel, Barcelona, Spain ISBN: 978-1-922069-84-9 McGregor. The modern understanding is related to psycho-sociological models (extrinsic-intrinsic dichotomy). Some authors propose anthropologic models as a way to amplify mainstream research within humanistic theories (i.e. Perez Lopez). Ryan and Deci (2000), the authors of the Self-Determination Theory, give an often-cited definition of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. Thus, they state that the intrinsically motivated individuals do something because it is leads to internal outcome (for internal pleasure of doing some action rather than for a separable consequence); whereas, extrinsically motivated do something because it leads to some separable outcome. Depending on how this separable outcome is integrated within the matrix of values of individual – different forms of extrinsic motivation are distinguished by the authors (“controlled behavior, introjected regulation, identified regulation and integrated regulation”) (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Intrinsic motivation and some forms of extrinsic motivation (identified and integrated) lead to the autonomous psychological states and, thus, coincide with increased creativity and productivity in completing the task. According to Ryan and Deci, it is important to know ones motivation. Depending on the goals the person sets for his career the results of his work might be different. Extrinsic motivation, associated with low autonomy, does not coincide with increased efficiency. Thus, extrinsic incentives may decline intrinsic motivation and provoke decreased efficacy. In parallel with Ryan & Deci, other authors claim that other sort of motivation, namely - ¨prosocial¨ or ¨transcedent¨ - also leads to unlocking the potential of an individual. For Grant, prosocial motivation is a desire or reason to act for the benefit of others or with the intention of helping others (Grant, 2011), (Grant, 2007), (Grant, 2008). For the purposes of this analysis, this type is defined as acting to achieve results that are inseparable from other person with high degree of autonomy. Prosocial and Intrinsic motivation show some synergy. Prosocial motivation strengthens the relationship between intrinsic motivation and creativity, core self-evaluations and performance, (Grant Berg, 2009), (Grant, 2008), (Grant Berry, 2011). Also, increases commitment (Grant, Dutton, 2008). Perez Lopez (1996) argues, that all types of motives – transcendent (prosocial), intrinsic, extrinsic (and corresponding types of needs – material, cognitive and affective) - should be fulfilled by an employer in the workplace because the interaction of intrinsic results (what obtains acting agent – his intrinsic and extrinsic goals) and transcendent results (what obtains the passive agent) of an action creates the optimal learning within any system (and any organization is a system). 3. The Methodology and Model The in-depth interviews were used, as this method will allow better conditions to concentration of the participant on their feeling and emotions and a higher degree of self-reflection. Proceedings of Annual Spain Business Research Conference 14 - 15 September 2015, Novotel Barcelona City Hotel, Barcelona, Spain ISBN: 978-1-922069-84-9 The sample is formed based on analytic generalization - the relevance to the existing theories (Yin, 2003, p 38). It was expected to obtain literal replication (as opposed to theoretical), by registering similar results for predictable reasons within the sample (Yin 2003, p 54). Following this logic, a multiple-case study was conducted. The cases selected for interview were female successors in Spanish family firms in Catalonia region, who were actively involved in management of the family company in the position of a director or CEO. As there is no common definition of family business, in this article an operational one will be used as basic. Derived from Miller & Le-Breton Miller (2007), Family Firm Institute (2013) and Spanish Ministry of Economy (DGPYME, 2003) to which a ¨continuation intent¨ is added (Litz, 1995), (FFI, 2013) as soon as succession is under scope. The definition follows: ¨Family Firm is one where two or more members of a family of different generations have an interest in ownership or in management and there is a commitment to the continuation of the venture and intention to keep control¨ The females were interviewed using predefined set of questions, and filled a small questionnaire with demographic data after the interview. The questionnaire and interview protocol can be find in appendix 1. The interviews were processed based on holistic model presentented in table 1. As it follows from literature review the three types of motivation have distinct theoretical grounds but might interfere with each other increasing or decreasing sense of autonomy and involvement of an individual. Proceedings of Annual Spain Business Research Conference 14 - 15 September 2015, Novotel Barcelona City Hotel, Barcelona, Spain ISBN: 978-1-922069-84-9 Motivation Amotivation Extrinsic (activity is done for a separable result of acting person) Table 1: Types of motivation Gradation Explication Result Lack of personalized intention to act External The results of an action regulation are separable from the acting person. Action is done to avoid external sanctions or obtain Low degree of externally imposed reward autonomy. Introjected The results of an action regulation are separable from the acting person. To avoid guilt or anxiety or to attain ego-enhancement and pride Identified The results of an action regulation are separable from the acting person, and are somewhat integrated in his matrix of values. Integrated The results of an action High degree of regulation are separable from the autonomy. acting person, but Improved completely integrated in efficiency and his matrix of values. The creativity. action is auto-determined The results of an action are inseparable from the person. The action is autodetermined. Intrinsic (activity is done for its inherent satisfactions of acting person) Prosocial, Transcedent (activity is done for inherent satisfactions of receiving person) Source: Own elaboration The results of an action are separable from the acting person and inseparable from receiving person. The action is autodetermined by acting person. High degree autonomy. Increased commitment 4. The Findings The main results of the study are presented in table 2 and then discussed. of Proceedings of Annual Spain Business Research Conference 14 - 15 September 2015, Novotel Barcelona City Hotel, Barcelona, Spain ISBN: 978-1-922069-84-9 Table 2. Results Motivation Some Examples Amotivation Obligation (only as a starting point) Extrinsic External regulation: Not mentioned (activity is Introjected regulation: Chance to prove personal abilities (to done for a make the company bigger, more professional…) separable Identified regulation: preference to work for family, belief that it result of acting is right and correct… person) Integrated regulation: Not mentioned Intrinsic Feeling of independence, feeling of involvement, enjoyment the (activity is work, because it is demanding, creative … done for its inherent satisfactions of acting person) Prosocial Enjoying the work because it is giving back to family, helping (activity is family, all job that my father did – will then you know – for done for what?; the business helps a lot of people, helping others to inherent spend a happy moment in their life… satisfactions of receiving person) Source: own elaboration 4.1. Extrinsic motivation The interviewees did not explicitly mention some typical extrinsic benefits – such as remuneration, flexibility of schedule or job security – that are typically associated with family business. A relatively small role of extrinsic motives was surprising to the author because a prior research based on literature review of articles on family business succession was indicating the presence of extrinsic factors (Akhmedova, 2015). 4.2. Intrinsic motivation As expected, the study showed robust results for intrinsic motivation as a driver of career choice. 4.3. Prosocial\Transcedent Transcedent or prosocial motives did not appear in family business literature to date; however, this study showed consistent results for this type of motivation. There are two themes. The first theme is ¨family¨ described as giving back to the family, continuation of something that a parent\parents were investing a lot of effort. Another - ¨customers¨ and ¨employees¨ represented by a belief that a product or service is helping a wide auditory of people, which constitutes a ¨family pride, a belief, that employees are happy and feel like in the family. This finding has important theoretical and practical implications. Proceedings of Annual Spain Business Research Conference 14 - 15 September 2015, Novotel Barcelona City Hotel, Barcelona, Spain ISBN: 978-1-922069-84-9 4.4. Results that Confirm Previous Research: 1. Interviewees had a long story of experiences related to family business, starting long before the succession occurred, in the age diapason of 1228 years. Starting to work as a hobby, or as a part internship for studies or getting to know different departments in summer. ¨I began to work like a hobby, it was not my job¨ ¨Because when my brother and I were young we started to work in summer… And we started from accounting and we saw administration department and then marketing, so we were in contact with company to see if we like or don’t like¨ ¨ I started with administration then marketing, even when I was studying I did some sales¨ 2. Motivation might change over time (i.e. from amotivation or obligation to intrinsic) 3. All interviewees had work experience outside the family company; thus, the process of making career choice involved comparing working experiences (but was not limited to it, as also personal factors mattered) 4. ¨Disruptive event¨ is a catalyst in making career choice ¨My father get ill and was from one day to another that could not carry the company, so he could not teach us and make a correct ¨traspaso¨ to give all the experience to the second generation. So for me was a challenge – I said: take it or not…¨ 4.5. Results That Do Not Confirm Previous Research: Women in the sample seemed to be quite proactive in terms of career development acquiring education and experience prior to entering family firm. Further, they seem to be highly involved into work (dedicating on average 9-10 hours daily), and taking it as a personal challenge. This finding confirms existing streams on career and career success, but does not support perceived discriminative practices cited in literature: primogeniture, gender role conflict, gender differences in early socialization and stimulation. 5. Summary and Conclusions Psychological factors and social experiences guide the process of career choice. First, the decision is based on comparison of work-related experiences (also possible alternatives) within and outside the family firm and a ¨disruptive event¨ often plays a role of catalyst – it is a moment to make a final decision. As it follows from interviews, early involvement into business do indeed creates a Proceedings of Annual Spain Business Research Conference 14 - 15 September 2015, Novotel Barcelona City Hotel, Barcelona, Spain ISBN: 978-1-922069-84-9 sense of commitment to the family enterprise. The healthy extent of such involvement would result in an ability of the next generation to look critically at this experience and to compare it with other job market opportunities and particular personal experiences outside the family company. The comparison of career options is done together with personal and psychological factors. The extent to which the person internalizes work in family firm plays important role. The presence of transcendent motivation might further increase commitment to family business. Such issues as ¨giving back to family¨, ¨supporting something that parents were building¨ and ¨making a positive impact¨ - is what creates additional value of family business in the eyes of the next generation daughters. This is probably due to a positive feedback from the part of other family members, employees and partners – as well, because of seeing the positive outcome in the form of increased effectiveness and benefits. The role of transcendent motivation was never discussed within the framework of family business, thus this paper makes important contribution to development of theory. Finally, the study provides some evidence that the social reality is changing gradually and women are becoming more active constructing their own lives and careers. Thus, it might be fruitful to change the research paradigm, when studying female underrepresentation, – from searching for ¨barriers¨ to concentrating on experiences and motivation. Although this research provided robust results on variety of theoretical issues, still, we don’t have answers to all questions. A quantitative research might provide statistical evidence to current findings. Further, an investigation, comparing entrepreneurs and successors might be needed to understand better the difference between the two and to refine current results. References Arthur, MB, Hall, DT and Lawrence, BS 1989, Handbook of career theory. New York: Cambridge University Press. Arthur, MB, Khapova, SN, and Wilderom, CP 2005, Career success in a boundaryless career world. Journal of organizational behavior, 26(2), pp 177-202. Bjuggren, P, & Sund, L 2001, Strategic decision making in intergenerational successions of smalland medium-sized family-owned businesses. Family Business Review, 14 (1), pp 11–24. Ceja, L, and Tàpies, J 2011, A model of psychological ownership in nextgeneration members of family-owned firms: A qualitative study. Chua, JH, Chrisman, JJ, Sharma, P, 1999, Defining the family business by behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 23 (4), pp 19–39. Deci, EL & Ryan RM 2000, Self-Determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), pp 68-78. Proceedings of Annual Spain Business Research Conference 14 - 15 September 2015, Novotel Barcelona City Hotel, Barcelona, Spain ISBN: 978-1-922069-84-9 Dumas, C 1989, Understanding of Father‐Daughter and Father‐Son dyads in Family‐Owned businesses. Family Business Review, 2(1), pp 31-46. Eagly, AH, and Johnson, BT 1990, Gender and leadership style: A metaanalysis. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 233. Eagly, AH, Johannesen-Schmidt, MC, & Van Engen, ML 2003, Transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles: A meta-analysis comparing women and men. Psychological Bulletin, 129(4), 569. Eagly, A, Johannesen-schmidt, M, & Engen, M, 2003, Transformational , Transactional , and Laissez-Faire Leadership Styles: A Meta-Analysis Comparing Women and Men. Psychological Bulletin, 129(4), pp 569–591. European Family Business Report 2012, June, Family Business Statistics. Retrieved from: http://www.europeanfamilybusinesses.eu/uploads/Modules/Publications/fa mily-business-statistics.pdf Grant, AM 2007, Relational job design and the motivation to make a prosocial difference. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), pp 393-417. Grant, AM, 2008, Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. Journal of applied psychology, 93(1), 48. Grant, AM & Berry, JW 2011 The necessity of others is the mother of invention: Intrinsic and prosocial motivations, perspective taking, and creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 54(1), pp 73-96. Grant, AM, Dutton, JE & Rosso, BD 2008 Giving commitment: Employee support programs and the prosocial sensemaking process. Academy of Management Journal, 51(5), pp 898-918. Hall, DT 1996 Protean careers of the 21st century. The Academy of Management Executive, 10(4), pp 8-16. Handler, WC 1989, Methodological issues and considerations in studying family businesses. Family business review, 2(3), pp 257-276. Hollander, BS & Bukowitz, WR 1990, Women, family culture, and family business. Family Business Review, 3(2), 139-151. Iannarelli, C 1992 The socialization of leaders: A study of gender in family business. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Pittsburgh. Instituto de la Empresa Familiar Report 2009 Retrieved from: http://www.iefamiliar.com/web/es/IEF_English.pdf Judge, TA, Higgins, CA, Thoresen, CJ, & Barrick, MR 1999 The big five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Personnel psychology, 52(3), pp 621-652. Lambrecht, J, & Donckels, R 2008, Towards a business family dynasty: a lifelong, continuing process. Handbook of research on family business, p 388. Litz, RA 1995, The family business: Toward definitional clarity. Family Business Review, 8(2), pp 71-81. López, JAP 1991 Teoría de la acción humana en las organizaciones: la acción personal (Vol. 6). Ediciones Rialp. López, JAP 1996, Fundamentos de la dirección de empresas (Vol. 31). Ediciones Rialp. Marshack, KJ 1994 Copreneurs and dual-career couples: Are they different? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 19, 49-49 Proceedings of Annual Spain Business Research Conference 14 - 15 September 2015, Novotel Barcelona City Hotel, Barcelona, Spain ISBN: 978-1-922069-84-9 McConaughy, D 1994, Founding-family-controlled corporations: An agencytheo- retic analysis of corporate ownership and its impact upon performance, operating efficiency and capital structure. Doctoral dissertation, University of Cinncinati. Miller, D, Steier, L, & Le Breton-Miller, I 2003, Lost in time: intergenerational succession, change, and failure in family business. Journal of business venturing, 18(4), pp 513-531. Miller, D, Le Breton-Miller, I, Lester, RH, & Cannella, AA 2007, Are family firms really superior performers?. Journal of Corporate Finance, 13(5), pp 829858. Ng TW, Eby, LT, Sorensen, KL, & Feldman, DC 2005, Predictors of objective and subjective career success: a meta‐analysis. Personnel psychology, 58(2), pp 367-408. Overbeke, KK, Bilimoria, D, & Perelli, S 2013, The dearth of daughter successors in family businesses: Gendered norms, blindness to possibility, and invisibility. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 4(3), 201212. Pascual Garcia, C 2012, Empresa Familiar: Mujer y Sucesión. Universidad de Cordoba. Sharma, P 2004, An overview of the field of family business studies: Current status and directions for the future. Family Business Review. Sharma, P & Irving, PG 2005, Four bases of family business successor commitment: Antecedents and consequences. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(1), pp 13-33. Simon 2009 The Lessons of the Hidden Champions in Hidden Champions of the Twenty-First Century 2009, pp 351-381 Stavrou, E 1996, Intergenerational transitions in family enterprise: factors influencing offspring intentions to seek employment in the family business(Doctoral dissertation, George Washington University). Stavrou, ET 1998, A four factor model: A guide to planning next generation involvement in the family firm. Family Business Review, 11(2), 135-142. Stavrou, ET 1999, Succession in family businesses: Exploring the effects of demographic factors on offspring intentions to join and take over the business. Journal of small business management, 37(3), 43. Stavrou, ET, & Winslow, EK 1996 Succession in entrepreneurial family business in the US, Europe and Asia: A cross-cultural comparison on offspring intentions to join and take over the business. International Council for Small Businesses. 41 I.C.S.B. World Conference 1996. Proceedings: Vol. 1, (pp 253- 273). Stockholm: ICSB Stavrou, ET Merikas, A & Vozikis, G 2008, Offspring intentions to join the family business does Culture Make a Difference? Theoretical Developments and Future Research in Family Business, (2002), pp 213–230. The Family Firm Institute, Inc. 2013 Family Enterprise: Understanding Families in Business and Families of Wealth, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, USA. Yin, R. 2003 Case study research: Design and methods, 3. Zellweger, T, Sieger, P, & Halter F 2011, Should I stay or should I go? Career choice intentions of students with family business background. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(5), pp 521-536. Ward, J. L. (1997). Growing the Family Business: Special Challenges and Best Practices. Family Business Review, 10(4), pp 323–337. Proceedings of Annual Spain Business Research Conference 14 - 15 September 2015, Novotel Barcelona City Hotel, Barcelona, Spain ISBN: 978-1-922069-84-9 Appendix Interview questions 1. Can you introduce your company and briefly explain your work? 2. Can you remember the moment in your life and the life of your family when you decided to enter family firm (and started this work)? 3. Can you reflect on some difficulties you experienced working for family firm? 4. Can you tell me about your family? What role the business played in everyday life? 5. How you see your role in family and business? What is your contribution? 6. How you understand ¨career success¨ Questionnaire after interview PART 1. The FIRM What is the age of the company? How many generations were working in the company? What is the turnover of the company approximately? Does the company operate internationally? Who founded the company? How many relatives of your generation are involved in the firm? How many of them are involved in management? How many of your brothers or sisters are involved in the firm? How many of them are involved in management? Is there a succession planning conducted? PART 2. Personal details What is your level education? (Master PhD MBA) Which field? How many years you are working for this company? How many hours a week you dedicate to your work? How many hours you dedicate to your family? Are you married? Do you have children? If yes – do they have intentions to work in family company?