Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference

advertisement

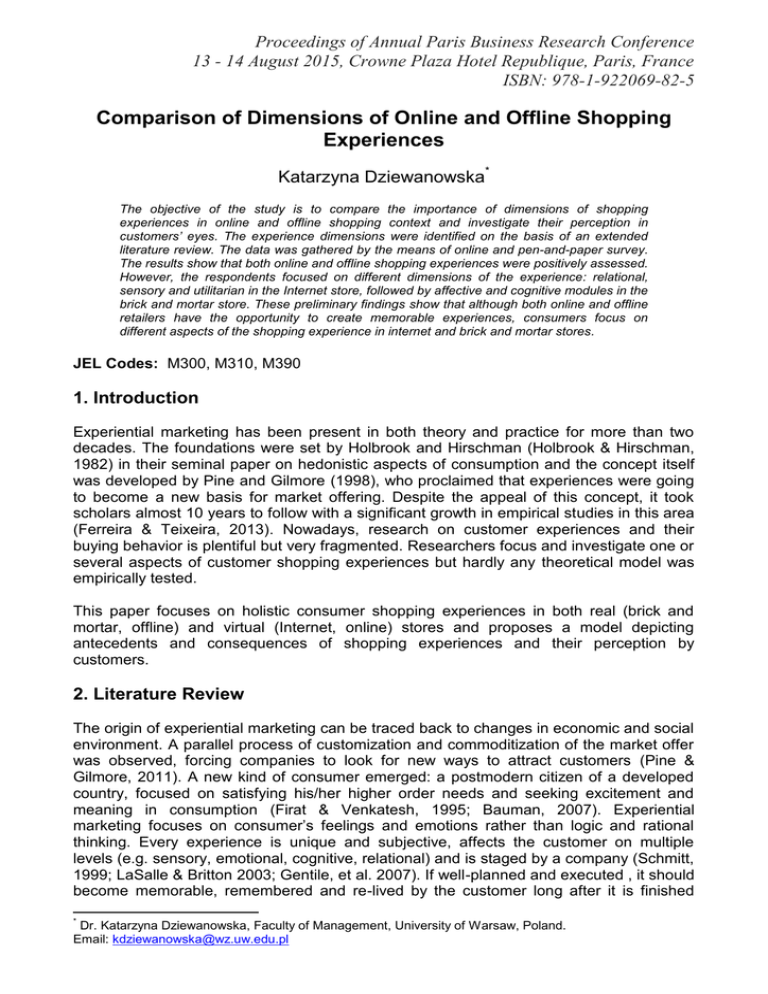

Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 Comparison of Dimensions of Online and Offline Shopping Experiences Katarzyna Dziewanowska* The objective of the study is to compare the importance of dimensions of shopping experiences in online and offline shopping context and investigate their perception in customers’ eyes. The experience dimensions were identified on the basis of an extended literature review. The data was gathered by the means of online and pen-and-paper survey. The results show that both online and offline shopping experiences were positively assessed. However, the respondents focused on different dimensions of the experience: relational, sensory and utilitarian in the Internet store, followed by affective and cognitive modules in the brick and mortar store. These preliminary findings show that although both online and offline retailers have the opportunity to create memorable experiences, consumers focus on different aspects of the shopping experience in internet and brick and mortar stores. JEL Codes: M300, M310, M390 1. Introduction Experiential marketing has been present in both theory and practice for more than two decades. The foundations were set by Holbrook and Hirschman (Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982) in their seminal paper on hedonistic aspects of consumption and the concept itself was developed by Pine and Gilmore (1998), who proclaimed that experiences were going to become a new basis for market offering. Despite the appeal of this concept, it took scholars almost 10 years to follow with a significant growth in empirical studies in this area (Ferreira & Teixeira, 2013). Nowadays, research on customer experiences and their buying behavior is plentiful but very fragmented. Researchers focus and investigate one or several aspects of customer shopping experiences but hardly any theoretical model was empirically tested. This paper focuses on holistic consumer shopping experiences in both real (brick and mortar, offline) and virtual (Internet, online) stores and proposes a model depicting antecedents and consequences of shopping experiences and their perception by customers. 2. Literature Review The origin of experiential marketing can be traced back to changes in economic and social environment. A parallel process of customization and commoditization of the market offer was observed, forcing companies to look for new ways to attract customers (Pine & Gilmore, 2011). A new kind of consumer emerged: a postmodern citizen of a developed country, focused on satisfying his/her higher order needs and seeking excitement and meaning in consumption (Firat & Venkatesh, 1995; Bauman, 2007). Experiential marketing focuses on consumer’s feelings and emotions rather than logic and rational thinking. Every experience is unique and subjective, affects the customer on multiple levels (e.g. sensory, emotional, cognitive, relational) and is staged by a company (Schmitt, 1999; LaSalle & Britton 2003; Gentile, et al. 2007). If well-planned and executed , it should become memorable, remembered and re-lived by the customer long after it is finished * Dr. Katarzyna Dziewanowska, Faculty of Management, University of Warsaw, Poland. Email: kdziewanowska@wz.uw.edu.pl Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 (Pine & Gilmore, 2011). Nowadays, yet another aspect of consumption has to be taken into consideration: its progressive virtualization. Internet, the key tool creating virtual reality, surrounds us like gas: invisible but always present (Saylor, 2012). The development of technology allows the consumer to satisfy a growing number of his/her needs online and thus studies on virtual aspects of consumption experiences become a valid research area (Jaciow & Wolny, 2011). There have been multiple attempts made at defining the dimensions of consumer experience. Some of them are based in theory and result in general typologies of experiences, such as two-dimensional approach of Pine and Gilmore (2011) or four dimensions of O’Sullivan and Spangler (1998). Others are derived from empirical research and result in identification of dimensions matching a particular kind of experience, e.g. tourism (Otto & Ritchie, 1996; Rageh, et al., 2013). Finally, there is a third way based in other fields of science, philosophy and psychology in particular. According to this approach, experiences are modular in nature and various researchers proffer different sets of modules: sensory perception, feelings and emotions, creativity and reasoning, and social relations (Pinker, 1997), sensory, affective, intellectual, behavioral, and relational (Schmitt, 1999) or sensory, emotional, cognitive, pragmatic, lifestyle, and relational (Gentile, et al., 2007). Such richness of conceptualizations proves that consumer experiences are a complex phenomenon requiring further investigation. From marketing perspective, the buying process is one of the key areas of analysis of consumer behavior. Companies strive to better understand how and why consumers make their purchases in order to provide them with engaging and memorable experiences leading to satisfaction, positive word of mouth and loyalty (Pine & Gilmore, 1999; Badgett, et al., 2007). Because of the subjectivity of customer experience, staging it requires precise knowledge on consumer needs and preferences, the buying process itself and interactions occurring between the consumer and the shopping environment. Although there is an extensive body of research on particular aspects of shopping experiences both online and offline (e.g. atmospherics (Ballantine, et al., 2010; Eroglu, et al., 2005), role of emotions (Andreu, et al., 2006), thinking style (Novak & Hoffman, 2008), there are few attempts at creating a comprehensive model of consumer shopping experiences, fewer of them actually being empirically tested (Verhoef, et al., 2009). Some models offer a very simplistic view of customer experiences in shopping context focusing mostly on company-controlled factors (e.g. price, assortment, location) (Grewal, et al., 2009), other concentrate on consumer’s internal processes (such as cognition, consciousness, affect) and resulting behavior (Fiore & Kim, 2007). The differences also include the temporal aspect: some models conclude that consumer shopping experiences begin and end in the store itself (Verhoef, et al., 2009), while others include the postpurchase effects of experiences (e.g. satisfaction and loyalty) (Rose, et al., 2012; Fatma, 2014). Moreover, most models apply to real or virtual shopping only and there is not a model that can be used for both of these realms. It can be concluded that there is a need for a multidimensional holistic model of consumer shopping experiences which can be applied to both online and offline shopping situations. In order to be managed, consumer experiences have to be understood and measured properly, along with their impact on marketing effects for the company. Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 3. The Methodology and Model This study is a part of a complex project on experiential economy in Poland. The objective of the study was to compare shopping experiences in a brick-and-mortar and an internet store with the use of the created measurement tool (see Fig.1). On the basis of previously realized research within the project (individual in-depth interviews) and extensive literature review we identified key dimensions of customer shopping experiences representing areas in which a company can interact with the customer in order to induce desirable reactions and states: Sensory (activated by sensory stimuli from the environment), Affective (focusing on mood, emotions and affect in shopping situations), Cognitive (resulting from thinking processes stimulated by interactions with a store), Utilitarian (practical aspects of shopping experiences, such as assortment, quality, convenience or, in case of Internet purchases, delivery), Symbolic (refers to the meaning customers attach to purchased products, stores and their lifestyles), Cost (covers wide range of customer costs: financial, psychological, temporal), Relations with employees (reflects the influence of sales personnel and service quality on customer experience), Relations with other customers (represents interactions with other customers and reactions to their presence), Escapist (aims at identifying the level of customer’s immersion in the experience resulting in time distortion). Figure 1: Holistic Model of Customer Experience in Shopping Context Sensory module Affective module Cognitive module Satisfaction Utilitarian module Symbolic module Total customer experience Word of Mouth Cost module Loyalty Relational module (employees) Relational module (other customers) Escapist module Source: Own research. Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 A positive customer experience should result in particular marketing effects desirable by a company. Such consequences of memorable experiences include customer satisfaction, willingness to recommend the store to other people and loyalty behavior understood as a repurchase intention and lower price elasticity (Oliver, 1999; Reichheld & Teal, 2001; Reichheld, 2003). The indexes constructed for each of the dimensions and marketing effects consisted of 314 items and their reliability was tested using SPSS v.22. For all of them Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient reached values satisfactory for newly-created indexes (Churchill & Peter, 1984; Nunnally, 1978) (see: Appendix). The research method was a survey conducted both online (CAWI) and offline (PAPI) on a sample of 120 customers of a store offering products for runners (specializing in running shoes). The store was chosen because of its ability to interact with customers in all of the pre-defined dimensions in real and virtual space. 96 respondents were selected purposefully for further analysis in order to achieve the similarity of online and offline samples in terms of gender, age, intensity of training and level of knowledge about equipment and training. Sample characteristics are presented in table 1. Table 1: Characteristics of research sample Characteristic Value Offline store Online store Female 20 20 Gender Male 28 28 18-35 years old 21 21 Age 36-50 years old 23 25 Above 50 years old 4 2 Low 8 8 Training Medium 32 32 intensity High 8 8 Low 10 9 Level of Medium 34 33 knowledge High 4 6 Source: Own research, N=96. The questionnaire which was used consisted of two parts. In the first part there were 57 items for the offline store and 61 items for the online one regarding the dimensions and marketing effects of the shopping experiences with the Likert scale anchored at 1(totally disagree) and 5 (totally agree). In the second part there were questions regarding the respondents’ characteristics such as age, gender, income, place of living, training details and knowledge about running. The survey was conducted between March and May 2015. 4. The Findings The analysis of the results of the survey show that there are differences between online and offline customer shopping experiences (see: Table 2). Both stores were positively assessed, although in the brick-and-mortar store, total customer experience index is 4.06, while in the virtual store it is 3.89 and the difference is statistically significant (see: Table 3). Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 Table 2: Assessment of experience dimensions and marketing effects in offline and online store Offline store Online store Standard Standard Mean Mean deviation deviation Sensory module 4.2470 0.42577 4.4083 0.50184 Affective module 4.1701 0.46444 3.7951 0.49969 Cognitive module 4.3160 0.58167 3.8299 0.50586 Utilitarian module 4.2411 0.45094 4.2857 0.41414 Symbolic module 3.8594 0.72733 3.6354 0.65631 Cost module 3.6833 0.52159 3.7833 0.53448 Relationship module (employees) 4.5917 0.43849 4.0458 0.68322 Relationship module (other 3.8229 0.61876 3.7014 0.76951 customers) Escapist module 3.1042 0.96043 2.3854 1.03907 Total experience index 4.0595 0.31895 3.8870 0.35406 Marketing effects: Satisfaction 4.2986 0.45735 4.1250 0.57376 Word of Mouth 4.4653 0.56174 4.2153 0.63948 Loyalty 3.6667 0.67722 2.9931 0.84632 Source: Own research. N=96. *1=totally disagree. 5=totally agree In the offline store the highest assessed module is the one reflecting the relationship with sales personnel (4.59), which is probably caused by a fact that purchased products require high involvement on the seller’s and buyer’s part and store employees actively advise the customers. Other highly assessed dimensions include cognitive (4.32), sensory (4.25), utilitarian (4.24) and affective (4.17) modules, which means that the store offers a pleasant, well-organized space where customers feel good and receive some intellectual stimulation. A module with the lowest score is the escapist one (3.10) suggesting that despite the positive shopping experience consumers claimed that they did not become fully immersed in it. The remaining dimensions (symbolic, cost and relationships with other customers) are also positively perceived, although their scores are below the one for the total experience. In the online store, the modules which were assessed highest include sensory (4.41) and utilitarian (4.29) ones as well as the relationship with employees module. It is interesting that despite the obvious limitations of websites, the sensory module here is assessed best. Similar observation can be made for the relationships with employees: although a direct contact is rare (possible by phone only), this dimension is perceived very positively. It can be a result of the “human presence” on the store website, examples of which include personal stories, photos from trainings, equipment advice, etc., and the generous complaint policy of the store. The high opinion on utilitarian aspect is not surprising here, as most customers name convenience one of the main reasons for shopping online (Jaciow & Wolny, 2011). It is only natural that the respondents chose the store which offered them the best conditions of purchase and delivery. An unexpected result is the one for the escapist module (2.39). Similarly to the offline store, this module received the lowest assessment among customers. Moreover, this is the only negatively perceived dimension. This stands in contrast to previous research which proved computer-mediated environment to foster the state of flow (Novak, et al., 2000; Mathwick & Rigdon, 2006). It Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 can mean that purchasing situations are not regarded as entertainment by customers who claim to remain in full control of time and money spent online while shopping. As far as marketing consequences of customer shopping experiences are concerned, it can be concluded that customers of both stores are highly satisfied and willing to recommend the stores to other people. The satisfaction index for the brick-and-mortar store is 4.43 and for the virtual one 4.13. The word of mouth index is 4.47 and 4.22 respectively. In these cases there are no statistically significant differences for both stores (see: Table 3). Interestingly, despite the high satisfaction and intention to positively recommend the stores, the loyalty index is much lower in both cases (3.30 and 2.99 respectively), although it is significantly higher for the offline store. Lower loyalty index for the online store is not surprising – after all, main reasons for making purchases in the Internet are cost, assortment width and convenience. With the availability of information and almost non-existent switching costs it is possible to find different, most suitable website each time a consumer decides to buy something. Table 3. Total experience and its effects in offline and online store Mann Asymp. Standard Variable Value Mean Whitney U Sig. deviation test (2-tailed) Total Offline store 4.0595 0.31895 experience 773.000 0.005 Online store 3.8870 0.35406 index Satisfaction Offline store 4.2986 0.45735 Online store 4.1250 0.57376 Offline store 4.4653 0.56174 Online store 4.2153 0.63948 Offline store 3.6667 0.67722 970.500 0.174 906.000 0.063 636.500 Online store 2.9931 0.84632 Source: Own research. N=96. *1=totally disagree. 5=totally agree Statistically significant results are bolded. 0.000 Word of Mouth Loyalty Analysis of correlations between marketing effects and customer shopping experiences allows for some interesting observations (see: Table 4). Firstly, the total customer experience index correlates strongly and positively with all marketing effects in the real and virtual stores, with the exception of recommendation index in the offline store where the correlation is moderate. Secondly, the strength of the correlation is diversified among particular experiential modules. Only two dimensions of shopping experience (affective and relations with employees) correlate with all indexes of customer satisfaction, WoM and loyalty in both stores. In the brick-and-mortar store, the strongest association can be observed between the experiences created by employees and customer satisfaction level. On the other hand, escapist module is the only one which has no relation to any of the marketing effects. A different situation can be observed in the online store. Here, five experiential dimensions are strongly associated with customer satisfaction (relations with employees, affective, cognitive, utilitarian, and cost), two with recommendation index (affective and cost) and two with customer loyalty (relations with employees and symbolic). There is also a Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 moderate correlation between escapist dimension of shopping experiences and customer loyalty. It can also be observed that positive experiences in online context more often and more strongly are associated with marketing consequences (only in 5 out of 30 instances the correlation coefficient is not statistically significant). In the brick and mortar store 10 of the correlations are insignificant. This may imply that with an offline store, which requires from the customer much more effort to visit, it takes more than a great shopping experience to become satisfied, recommending and loyal. Table 4. Spearman’s Rho correlation coefficient: experiential modules and marketing effects Offline store Online store Word SatisWord of SatisLoyalty of Loyalty faction Mouth faction Mouth Sensory module 0.408** 0.261 0.331* 0.302* 0.423** 0.031 Affective module 0.383** 0.311* 0.343* 0.527** 0.571** 0.292* Cognitive module 0.419** 0.074 0.323* 0.529** 0.409** 0.495** Utilitarian module 0.481** 0.373** 0.192 0.243 0.527** 0.495** Symbolic module 0.312* 0.183 0.377** 0.431** 0.490** 0.541** Cost module 0.313* 0.144 0.224 0.216 0.532** 0.558** Relationship module 0.449** 0.292* 0.624** 0.452** 0.539** 0.646** (employees) Relationship module 0.277 0.287* 0.300* 0.497** 0.361* 0.381** (other customers) Escapist module 0.106 0.105 0.162 0.185 0.183 0.353* Total experience 0.406** 0.592** 0.538** 0.756** 0.722** 0.641** index **p<0.01; * p<0.05 Source: Own research. N=96. Strong (<0.5; 0.7>) correlations are bolded. 5. Summary and Conclusions The experiential marketing is currently one of the answers to changes occurring in social, economic and technological environment. When selecting a store, customers frequently expect not only a satisfying product or service but also an experience which can touch them on many levels: emotional, intellectual or symbolic. Moreover, with the widespread use of the Internet, a significant part of consumer activities is transferred online, including shopping behavior. In order to stage compelling experiences it is crucial to understand how an experience is created, what are its dimensions and what are the consequences of company’s activities on consumer’s behavior and attitude. This paper presents an empirically verified model of customer experience in shopping situations. Nine dimensions and three consequences of customer experiences are identified and tested for their reliability. The sets of dimensions are identical for online and offline stores and in six instances the items in each index are the same. The remaining three (sensory, utilitarian and relations with other customers) are different as it reflects the differences between the real and virtual spaces. Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 Further analysis of the model allows for the conclusion that despite the obvious differences between online and offline stores, it is possible to create positive and multidimensional experiences for customers. However, in discussed study, it seems that the real store created positive experiences in more dimensions than the offline store. It should be considered, to which extent such situation results from company’s (more or less) successful activities and to which extent it is a result of different customer’s needs and expectations. Moreover, the results of the study imply that positive total shopping experience results in customer satisfaction, willingness to recommend and loyalty. This is an important clue for store managers who should incorporate differentiated stimuli in their operations and focus on staging memorable experiences in order to win customers. This seems to be especially true for online stores – here most of experiential dimensions correlated with marketing effects. Perhaps staging compelling and rich customer experiences is a valid strategy to create a significant advantage in this highly competitive environment. The current study is not without its limitations. Firstly, the empirical verification of the model was conducted in a single, hobby-related store and on a relatively small sample. Therefore, future research should focus on comparative analysis of various shopping contexts and larger samples. Secondly, the study concerns Polish customer, born and raised in particular market conditions, which might affect the results. Thus, it is advisable to study the influence of cultural environment on customer experiences as well. End Notes This paper is based on research conducted as part of a project funded by Narodowe Centrum Nauki (National Science Centre): decision number DEC-2012/05/B/HS4/04213. References Andreu, L., Bigné, E., Chumpitaz, R. & Swaen, V., 2006. How does the perceived retail environment influence consumers emotional experience? Evidence from two retail settings. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, Volume 16, pp. 559-578. Badgett, M., Boyce, S. M. & Kleinberger, H., 2007. Turning Shoppers into Advocates. Somers, NY: IBM Institute for Business Value. Ballantine, P. W., Jack, R. & Parsons, A. G., 2010. Atmospheric cues and their effect on the hedonic retail experience. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, Vol. 38, pp. 641-653. Bauman, Z., 2007. Konsumenci w społeczeństwie konsumentów. Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego. Churchill, G. J. & Peter, J., 1984. Research Design Effects on the Reliability of Rating Scales: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 21(4), pp. 360-375. Eroglu, S. A., Machleit, K. A. & Davis, L. M., 2005. Empirical Testing of a Model of Online Store Atmospherics and Shopper Responses. Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 20, pp. 139-150. Fatma, S., 2014. Antecedents and Consequences of Customer Experience ManagementA Literature Review and Research Agenda. International Journal of Business and Commerce, Vol. 3, pp. 32-49. Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 Ferreira, H. & Teixeira, A., 2013. 'Welcome to the experience economy': assessing the influence of customer experience literature through bibliometric analysis. Working Papers (FEP) - Universidade do Porto(481), pp. 1-28. Fiore, A. & Kim, J., 2007. An integrative framework capturing experiential and utilitarian shopping experience. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, Vol. 35, pp. 421-442. Firat, A. & Venkatesh, A., 1995. Liberatory Postmodernism and the Reenchantment of Consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 22, pp. 239-267. Gentile, C., Spiller, N. & Noci, G., 2007. How to sustain the customer experience: An overview of experience components that co-create value with the customer. European Management Journal, 25(5), pp. 395-410. Grewal, D., Levy, M. & Kumar, V., 2009. Customer Experience Management in Retailing: An Organizing Framework. Journal of Retailing, Vol. 85, pp. 1-14. Holbrook, M. & Hirschman, E., 1982. The Experiential Aspects of Consumption: Consumer Fantasy, Feelings and Fun. Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 9, pp. 132-140. Ismail, A. R., Melewar, T., Lim, L. & Woodside, A., 2011. Customer experience with brands: Literature review and research directions. The Marketing Review, 11(3), pp. 205-225. Jaciow, M. & Wolny, R., 2011. Polski e-konsument. Typologia, zachowania. Gliwice: Helion. LaSalle, D. & Britton, T., 2003. Priceless: Turning Ordinary Products into Extraordinary Experiences. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. Mathwick, C. & Rigdon, E., 2006. Play, flow, and the online search experience. Journal of Consumer Research, Volume 31, pp. 324-332. Novak, T. & Hoffman, D., 2008. The Fit of Thinking Style and Situation: New Measures of Situation-Specific Experiential and Rational Cognition. Journal of Consumer Research, Volume 36, pp. 56-72. Novak, T., Hoffman, D. & Yung, Y., 2000. Measuring the Customer Experience in Online Environments: A Structural Modeling Approach. Marketing Science, Vol. 19, pp. 2242. Nunnally, J., 1978. Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. Oliver, R., 1999. Whence Consumer Loyalty?. Journal of Marketing, Volume 63, pp. 3344. O'Sullivan, E. & Spangler, K., 1998. Experience Marketing: Strategies for the new millennium. State College, PA: Venture Publishing. Otto, J. E. & Ritchie, J. B., 1996. The service experience in tourism. Tourism Management, Vol. 17, pp. 165-174. Pine, J. & Gilmore, J., 1998. Welcome to the Experience Economy. Harvard Business Review, July-August, pp. 97-105. Pine, J. & Gilmore, J., 2011. The Experience Economy. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press. Pinker, S., 1997. How the Mind Works. New York: Norton. Rageh, A., Melewar, T. C. & Woodside, A., 2013. Using netnography research method to revel the underlying dimensions of the customer/tourist experience. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, Vol. 16, pp. 126-149. Reichheld, F. & Teal, T., 2001. The Loyalty Effect: The Hidden Force Behind Growth, Profits, and Lasting Value. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. Reichheld, F., 2003. The Ultimate Question: Driving Good Profits and True Growth. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. Proceedings of Annual Paris Business Research Conference 13 - 14 August 2015, Crowne Plaza Hotel Republique, Paris, France ISBN: 978-1-922069-82-5 Rose, S., Clark, M., Samouel, P. & Hair, N., 2012. Online Customer Experience in eRetailing: An empirical model of Antecedents and Outcomes. Journal of Retailing, Vol. 88, pp. 308-322. Saylor, M., 2012. The Mobile Wave: How Mobile Intelligence Will Change Everything. New York: Vanguard Press. Schmitt, B., 1999. Experiential Marketing: How to Get Customers to SENSE, FEEL, THINK, ACT and RELATE to Your Company and Brands. New York: The Free Press. Shaw, C. & Ivens, J., 2002. Building great customer experiences. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Verhoef, P. C., Lemon, K. N., Parasuraman, A., Roggeveen, A., Tsiros, M.& Schlesinger, L. A. 2009. Customer experience creation: Determinants, dynamics and management strategies. Journal of Retailing, Vol. 85, pp. 31-41. Appendix Table 6: Reliability of scales: experiential modules and marketing effects Offline store Online store Cronbach’s Cronbach’s Number Number Alpha Alpha of items of items coefficient coefficient Sensory module 7 0.749 5 0.758 Affective module 6 0.719 6 0.755 Cognitive module 6 0.859 6 0.798 Utilitarian module 7 0.612 14 0.860 Symbolic module 4 0.788 4 0.777 Cost module 5 0.644 5 0.727 Relationship module 5 0.756 5 0.941 (employees) Relationship module (other 4 0.529 3 0.686 customers) Escapist module 4 0.860 4 0.920 Total experience index 48 0.886 52 0.923 Marketing effects: Satisfaction 3 0.679 3 0.794 Word of Mouth 3 0.806 3 0.915 Loyalty 3 0.721 3 0.801 Source: Own research. N=96.