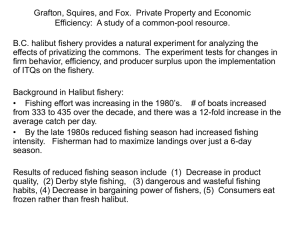

Economic Implications of a Strategy to Purchase Alaska Halibut

advertisement