Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 28(2), September – October 2014; Article No. 47, Pages: 263-266

ISSN 0976 – 044X

Research Article

Evaluation of Higher Education Service Quality Scale in Pharmaceutical Education

*

V.S. Sheeja , R. Krishnaraj, R.M. Harindranath

SRM Faculty of Management, SRM University, Kattankulathur, Tamil Nadu, India.

*Corresponding author’s E-mail: vssheeja76@hotmail.com

Accepted on: 31-08-2014; Finalized on: 30-09-2014.

ABSTRACT

This Study evaluates the HEdPERF (Higher Education Performance) scale, a measuring instrument of service quality in higher

education sector. The scale has been empirically tested for unidimensionality, reliability and validity using both exploratory and

confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Such valid and reliable measuring scale would be a tool that higher education institutions could

use to improve service performance to retain the number of pharmaceutical students and to capture the global education markets.

Research findings confirmed the role of key factors in service quality. These four factors such as Non-Teaching Staff, Teaching staff,

Access and Reputation possess psychometric properties of construct validity. Their reliabilities are high which indicates that these

variables/constructs are suitable for measuring the service quality of Indian Pharmacy education. The researcher wants to test this

scale with different population of India, to discover the reliability and validity of the scale in Pharmaceutical Education. The

limitation could be the development of some factors which are specific to pharmacy Education domain. Thus, this scale can be made

comprehensively define the second order factor “Service Quality”.

Keywords: Service quality, pharmaceutical education, HEdPERF scale, reliability, construct validity, CFA

INTRODUCTION

H

igher education is considered a part of service

industry since the primary focus of tertiary

institutions is to provide quality learning

experiences to students. With the proliferation of study

options available to students internationally including the

use of virtual technology to deliver courses, it is no

wonder tertiary institutions worldwide are under

pressure to provide unique learning experiences to

students so as to capture the market share. Hence,

service quality becomes the means for many institutions

to retain student numbers and to capture the educational

1

market.

The most common understanding of service quality is its

association with teacher-student participation in relation

to the professionalism-intimacy scale as affecting

immediate and lifelong learning. However, service quality

is far more complex, it is concerned with the physical,

institutional and psychological aspects of higher

education. For instance, Li and Kaye (1998) argue that

service quality deals with the environment, corporate

image and interaction among people. They distinguish

between process and output quality, where the former is

judged by customers during the service and the latter,

after the service.

Parasuraman et al., 1994; Dabholkar et al., 2000; Brady et

al., 2002 recommends measuring student satisfaction

with the services provided at the universities. Higher

education is realized as “experienced goods” (Petruzzellis

et al., 2006), and the university is a unique service

provider; it offers a variety of tangible services in terms of

infrastructural facilities and technology, whereas, its core

service teaching and learning remains intangible and

covert.

The unique characteristics of services make

conceptualization and measurement of service quality

very challenging, especially in the context of higher

education. The unique and intangible service – higher

education leaves long-range effects on quality of life of

individual students influencing the whole fabric of society,

while playing a vital role in its evolution.2

The pressure on universities to produce quality graduates

is ever increasing. Moreover, universities are driven

toward retaining their customers, realizing that

sustainability depends upon the service quality they

provide to students, their primary customers. Service

quality has become the cutting edge, which distinguishes

universities, contextualized in terms of a well-planned

and well-delivered service and sets them from their

3

competitors.

A survey conducted by Owlia and Aspinwall (1997)

examined the views of different professionals and

practitioners on the quality in higher education and

concluded that customer-orientation in higher education

is a generally accepted principle. They construed that

from the different customers of higher education,

students were given the highest rank. Student experience

in a tertiary education institution should be a key issue of

which performance indicators need to address. Thus it

becomes important to identify determinants or critical

factors of service quality from the standpoint of students

being the primary customers. Firdaus Abdullah*2006

point out that it is important for tertiary institutions to

International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research

Available online at www.globalresearchonline.net

© Copyright protected. Unauthorised republication, reproduction, distribution, dissemination and copying of this document in whole or in part is strictly prohibited.

263

© Copyright pro

Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 28(2), September – October 2014; Article No. 47, Pages: 263-266

provide adequate service on all dimensions, and then

possibly to ascertain which dimensions may require

greater attention. For instance, quality improvement

programs should address not only the performance of

service delivery by the academics, but also the various

aspects surrounding the educational experience such as

physical facilities, and the multitude of support and

advisory services offered by the institutions.4,5

Helms and Key (1994) noted that students could be

classified as a raw material, customer, or even as

employees. As a raw material, students move through a

process and become the end product. As customers,

students purchase the service of education. Helms and

Key noted that students must be engaged in their studies,

must be motivated to perform, and are evaluated – them

much like employees.

In addition, quality of student performance is important

to a university in much the same way that quality of

employee performance is important in business setting.

Further analysing the differing roles of students, Helms

and Key (1994) pointed out that different educational

settings provide different roles for students. In large,

introductory classes the students are very much like

customers; however, in specialised graduate research

settings students are more like employees.6

According to Garvin (1988), service quality is a complex

and volatile issue, largely driven by contextual

unpredictability and complexity. Improving service quality

does not happen overnight; it requires a persistent

endurance to withstand the test of time through

collective mindsets and efforts. Success depends on the

dynamic exchange of mental models of both and nonacademic staff in achieving service quality. Although such

individual attributes as attitude and motivation may be

difficult to modify over a short period, given the right

stimulus through, for instance, an appropriate reward and

compensation system, mental models can be changed for

the benefit of the institution. One possibility would be to

institutionalize appropriate systems within educational

settings to facilitate a community of practice across all

levels. That is the way to go for higher education in a

7

changing world.

Mohammad S. Owlia et.al1996 suggests the first step in

satisfying customer needs is the determination of how

quality dimensions/factors are perceived by each group.

This information, together with the prioritized objectives

of a particular institution, will form the platform from

which a quality program can be developed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In terms of measurement methodologies, a review of

literature provides plenty of service quality evaluation

scales. A survey of the services marketing literature

reveals two main approaches to measure service quality:

SERVQUAL and SERVPERF (Cronin and Taylor, 1992). One

of the most popular methods, called SERVQUAL, has its

theoretical foundations in the gaps model and defines

ISSN 0976 – 044X

service quality in terms of the difference between

customer expectations and performance perceptions on a

number of 22 measures.8

The SERVQUAL instrument, “despite criticisms by a

variety of authors, still seems to be the most practical

model for the measurement of service quality available in

the literature” and thus expectations should be

considered when assessing service quality in Higher

Education (HE, here after). Regarding the stability of

expectations and perceptions of service quality over time,

in scope of HE, it was empirically concluded that student’s

perceptions of service experienced proved less stable

9,10

over time than expectations.

More recently, a new industry-scale, called HEdPERF was

developed comprising a set of 41 items. This instrument

aims at considering not only the academic components,

but also aspects of the total service environment as

experienced by the student. The author identified five

dimensions of the service quality concept such as Nonacademic, academic, aspects, reputation, program issues

and understanding. Items that are essential to enable

students to fulfill their study obligations, and relate to

duties carried out by non-academic staff. Through

questionnaire designed based on quality dimensions of

the introduced techniques, perceptions and expectations

among the stakeholders can be analysed.11

Sampling method

The sampling method used in the study is convenience

sampling. Data were collected from pharmacy students of

both public university and private university in Chennai,

for the period between October-December 2013. Data

had been collected using the “personal-contact”. The

questionnaires were administered with paper and pencil

approach among respondents.

Measures

Data were collected by using a questionnaire which is

composed of 41 items adopted from the original HEdPERF

(Firdaus, 2005), a scale uniquely developed to embrace

different aspects of public and private institution’s service

offering to the students. The questionnaire is tested with

a group of students to check the reliability, content

validity, as a part of pilot study. This scale is generated

and validated within higher education domain and along

with the results of the pilot study suggest that no scale

modification was required.

All the items in were presented as statements on the

questionnaire, with the same rating scale used

throughout, and measured on a 7-point, Likert-type scale

that varied from 1 for strongly disagree to 7 for strongly

agree. In addition to the main scale addressing individual

items, respondents were asked to provide an overall

rating of the service quality, satisfaction level.

There were also three open-ended questions allowing

respondents to give their personal views on how any

12

aspect of the service could be improved.

International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research

Available online at www.globalresearchonline.net

© Copyright protected. Unauthorised republication, reproduction, distribution, dissemination and copying of this document in whole or in part is strictly prohibited.

264

© Copyright pro

Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 28(2), September – October 2014; Article No. 47, Pages: 263-266

The draft questionnaire was eventually subjected to pilot

testing with a total of 50 students, and they were asked

to comment on any perceived ambiguities, omissions or

errors concerning the draft questionnaire. Data were

collected from students of both public universities and

private university in Chennai, for the period between

October –December 2013. Data had been collected using

the “personal-contact” approach.

ISSN 0976 – 044X

Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) and Root Mean square error of

Approximation (RMSEA). In accordance Bentler the model

fit is satisfactory where the GFIm, CFI and TLI exceeds 0.9

19

and RMSEA values are less than 0.08.

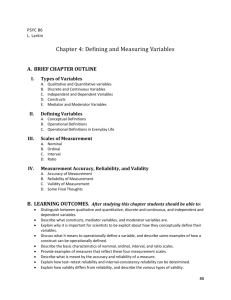

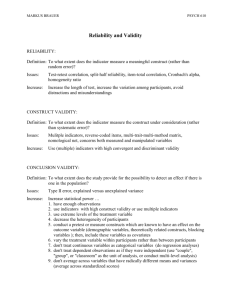

Table 1: Correlations, Descriptive Statistics & Cronbach

alpha.

Correlations

Construct

Mean

A total of 500 questionnaires were distributed to both

public and private university, of these 410 was returned

and ten discarded due to incomplete responses. The

number of usable sample size is 400.

No of

Items

Standard

Deviation

1

Non

Teaching

Staff

4

4.06

1.39

α=.86

Access

5

4.53

1.23

.558

**

α=.87

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Academic

Aspects

.524

**

.361

**

α=.86

.539

**

.467

**

.601

6

4.17

1.34

2

3

Measurement assessment

Reputation

There are missing data in the questionnaire and this is

imputed using Mean Imputation using SPSS 21. The

reliability of all the constructs are above .8 indicate good

reliability expect the one construct whose reliability is

77.13,14

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

The exploratory factor analysis used to extract the items

for each construct by using principal component analysis

as it is commonly used method of parameter estimation.

The four constructs were extracted by using Varimax

rotation and this rotation is commonly used in Factor

analysis.

During the factor analysis, 23 items were deleted due to

cross loadings of items and low communality values (less

than 0.5) to more than one factor and poor factor

loadings of the items. The remaining items are statistically

significant as the t-values are in the range of 9.48 to

11.81, which are high.

From the methodology laid by a measurement model was

specified using Amos 21 by confirmatory Factor Analysis.

The measurement model will determine the convergent

and discriminant validity of the constructs and this will

assess the psychometric properties of the constructs.

Very recently, (Aguinis & Edwards, 2014) advises to use

confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to evaluate the

construct validity.15,16

Multivariate normality was evaluated using Mardia’s

coefficient and the data was found to be non-normal as

the multivariate kurtosis (critical ratio) was 29, which

was much above ±2 and suggest, moderate multivariate

non-normality. Owing to the non-normal data, we use

Bollen-Stine bootstrapping method using 5000 samples

for parameter estimation as bootstrapping distribution

does not have rigorous assumptions like normal

distribution.17,18

Measurement model

The measurement model was analyzed using Amos 21

software with Maximum Likelihood Estimation. The fit

indices values used to assess the CFA model are Cmin/df,

Goodness of fit index (GFI), Comparative fit index (CFI),

3

4.26

1.43

4

**

α=.77

Table 2: Factors validity using CFA

Parameters

Value

Desirable Values

Cmin/df (degrees of freedom)

2.075

<3

2

Goodness of Fit (GFI)

0.912

> 0.9

3

IFI (Incremental fit Index)

0.953

> 0.9

4

CFI (Confirmatory fit index)

0.952

> 0.9

5

TLI (Tucker Lewis index)

0.953

> 0.9

6

Root Mean Square Error of

Approximation (RMSEA)

0.60

< 0.7

1

Construct validity

The two important validity are convergent and

discriminant validity. To measure the convergent validity,

Average variance extracted (AVE) calculated must be

above 0.5 and the path coefficient must be above 0.6. The

AVE for all the constructs are above 0.5 and the construct

reliabilities are above 0.7 suggest the convergent validity.

The squared inter construct correlation value of all the

constructs are lower than the AVE values indicate the

discriminant validity. The correlations between constructs

are significant shows nomological validity. Thus the

constructs used in the study possess convergent,

Discriminant & nomological validity.

Table 3: Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Construct

Reliability & Squared Correlation.

squared Inter

construct correlation

Constructs

AVE

Construct

Reliability

2

3

4

1. Non Teaching Aspects

0.6

0.86

0.34

0.36

0.33

2. Teaching Aspects

0.6

0.80

0.29

0.50

3. Access

0.6

0.87

4. Reputation

0.5

0.84

0.17

AVE is Average Variance extracted

We have analyzed to estimate the impact of common

method variance as this data collected is self reporting.

International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research

Available online at www.globalresearchonline.net

© Copyright protected. Unauthorised republication, reproduction, distribution, dissemination and copying of this document in whole or in part is strictly prohibited.

265

© Copyright pro

Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 28(2), September – October 2014; Article No. 47, Pages: 263-266

Using the Harman’s single Factor test, the variance

extracted by a single factor is 33% which is less than 50%,

indicates that there is no problem due to common

method bias. In order to confirm further, we did a latent

common factor method and found that the factor loading

do not change much with and without the common

factor.20

CONCLUSION

The results indicate that there are four factors which

serve as factors for service quality. These four factors are

Non-Teaching aspects; Teaching Aspects, Access and

Reputation possess psychometric properties of construct

validity. There reliabilities are high which indicates that

these variables/constructs are suitable for measuring the

service quality of Indian Pharmacy education. The

researcher wants to test this scale to other sample in

different population, to discover the reliability and

validity of the scale. Meanwhile some factors can be

developed which are Domain specific with respect to

Pharmaceutical Education. Thus, this scale can be made

comprehensively define the second order factor “Service

Quality”. The future research could be adding certain

variables thus performing a partial scale development

process.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Yeo RK, Brewing service quality in higher education:

characteristics of ingredients that make up the recipe,

Quality Assurance in Education, 16 No 3, 2008, 266-286.

Parasuraman A, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL, Reassessment of

expectations as a comparison standard in measuring

service quality: implications for future research, Journal of

Marketing, 58, 1994, 111–124.

Kanji GK, Tambi AMA, Wallace W, A comparative study of

quality practice in higher education institutions in the US

and Malaysia, Total Quality Management, 10 No. 3, 1999,

357-371.

Owlia MS, & Aspinwall EM, TQM in higher education—a

review, International Journal of Quality & Reliability

Management, 145, 1997, 527–543.

Abullah Firadulla, Measuring service quality in higher

education: Three instruments compared. International

Journal of Research and method in education 26 No 1,

2006, 71-89.

Helms SK, Key H, Are students more than the customers in

the class room? Quality progress, 27, 1994, 97-99.

ISSN 0976 – 044X

7.

Garvin DA, Managing Quality, The Free Press, New York,

NY. 1988.

8.

Cronin JJ, Taylor SA, Measuring service quality:

reexamination and extension. Journal of Marketing, 56,

1992, 55–68

9.

Parasuraman A, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL, SERVQUAL: a

multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of

service quality, Journal of Retailing, 6 No 41, 1988, 12-40.

10. Hill FM, Managing service quality in higher education: the

role of student as primary consumer. Quality Assurance in

Education, 3, 1995, 10–21.

11. Abdullah F, Measuring service quality in higher education:

HEdPERF versus SERVPERF. Marketing Intelligence &

Planning, 24 No1, 2006a, 31–47.

12. Abdullah F, Measuring service quality in higher education:

three instruments compared. International Journal of

Research & Method in Education, 291, 2006b, 71–89

13. Hair, Joseph F, Tatham, Ronald L, Anderson, Rolph E, &

Black, William. Multivariate data analysis: Pearson Prentice

Hall Upper Saddle River, NJ 6, 2006

14. Nunnally, Jum C, Bernstein, Ira H, & Berge, Jos MF ten..

Psychometric theory McGraw-Hill New York. 226, 1967

15. Anderson, James C, & Gerbing, David W, Structural

equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended

two-step approach. Psychological bulletin, 103, No 3, 1988,

411.

16. Aguinis, Herman, & Edwards, Jeffrey R. Methodological

wishes for the next decade and how to make wishes come

true. Journal of Management Studies, 51, No 1, 2014, 143174.

17. Singh, Ramendra, & Das, Gopal. The Impact of Job

Satisfaction, Adaptive Selling Behaviors, and Customer

Orientation, on Salesperson’s Performance: Exploring the

Moderating Role of Selling Experience. Journal of Business

& Industrial Marketing, 28, No 7, 2013, 3-3.

18. Byrne, Barbara M. Structural equation modeling with

AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming:

Routledge. 2013

19. Bentler, Peter M. On the fit of models to covariances and

methodology to the<em> Bulletin.</em>. Psychological

bulletin, 112, No 3, 1992, 400.

20. Podsakoff, Philip M, MacKenzie, Scott B, Lee, Jeong-Yeon, &

Podsakoff, Nathan P. Common method biases in behavioral

research: a critical review of the literature and

recommended remedies. Journal of applied psychology, 88

No 5, 2003, 879.

Source of Support: Nil, Conflict of Interest: None.

International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research

Available online at www.globalresearchonline.net

© Copyright protected. Unauthorised republication, reproduction, distribution, dissemination and copying of this document in whole or in part is strictly prohibited.

266

© Copyright pro