Document 13307543

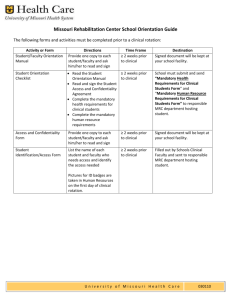

advertisement