The Farmer and the Tax Man: in Chapter 12 Bankruptcy I.

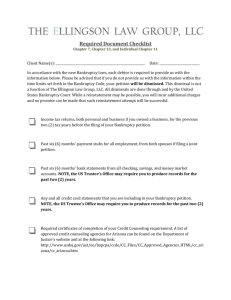

advertisement