Leveraging Tribal Sovereignty for Economic Opportunity: A Strategic Negotiations Perspective T

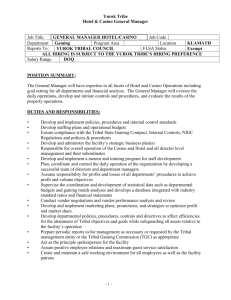

advertisement