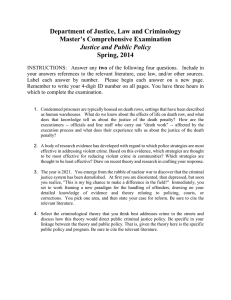

NOTE Swimming Against the Tide: The Eighth

advertisement