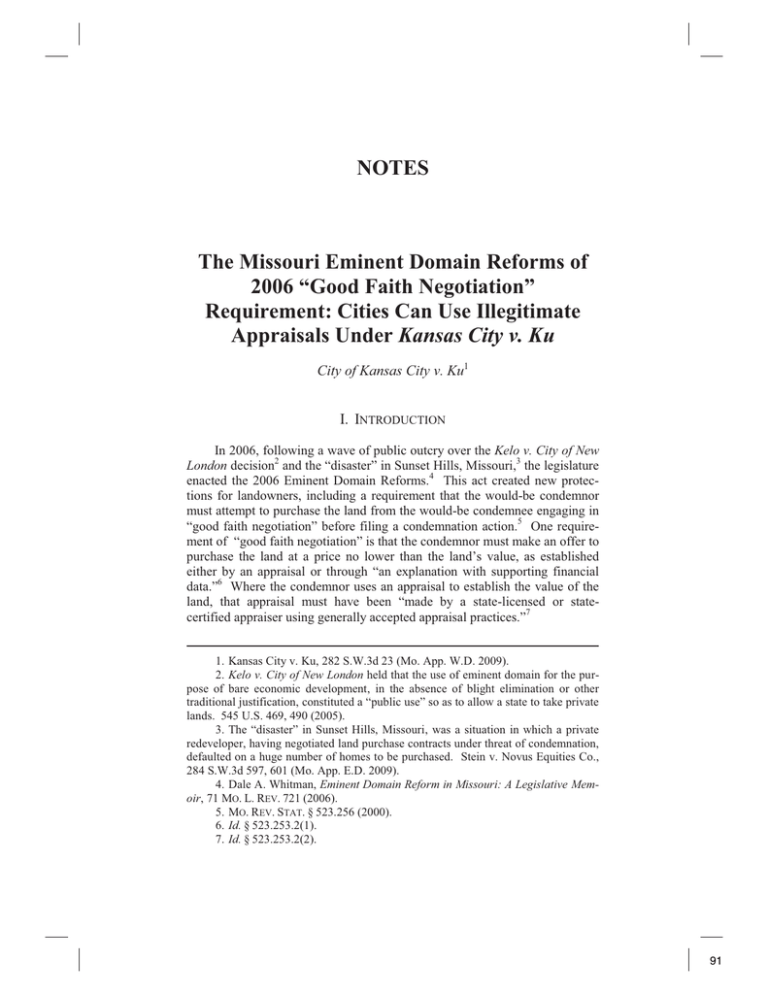

NOTES The Missouri Eminent Domain Reforms of 2006 “Good Faith Negotiation”

advertisement