Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts Mecklenburg County

advertisement

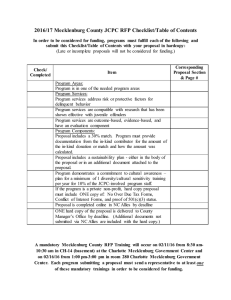

Justice Reinvestment at the Local Level: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts Mecklenburg County April 3, 2013 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts Table of Contents Page # Executive Summary i Background and Introduction 1 Methods 2 Findings 4 Key Findings of Interest 9 Key Finding 1: Low Level Offenses 9 Key Finding 2: Mental Illness/Homelessness (Frequent Jail Utilizers) 13 Key Finding 3: Recidivists 16 Cost Impact Projections 20 Proposed Strategies 20 Next Steps 22 Appendix 23 Applied Research Services, Inc. 663 Ethel Street, NW Atlanta, GA 30318 404-881-1120 www.ars-corp.com resources by this small group of persons. One possible means of addressing these offenders, many of whom are likely to be suffering from mental illness, would be to have officers who have received Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training respond to these arrest situations. Executive Summary Justice Reinvestment at the Local Level Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts Mecklenburg County April 3, 2013 Key Finding #3: Recidivists A large percentage of offenders recidivate, after having been released either from the jail or to Mecklenburg County from North Carolina prisons. Recidivists look very similar to non-recidivists in terms of their personal and offense characteristics. Given the proportion of these episodes which involved a probation or parole violation (12%), any reduction in arrests for these charges would be felt most acutely in a reduction in jail bed days, given the relatively high proportion of bed days consumed by probation/parole violators. The Justice Reinvestment Initiative (JRI) was launched by the United States Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) in 2006 in order to address the increase in corrections spending at both the state and local levels. The JRI efforts in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina built upon and augmented the work of the preexisting Mecklenburg County Criminal Justice Advisory Group (CJAG). Oversight and coordination of the JRI efforts in Mecklenburg County was provided by Thomas Eberly, Criminal Justice Manager for Mecklenburg County. Training and Technical Assistance has been provided to Mecklenburg County by the Center for Effective Public Policy (CEPP) and Applied Research Services (ARS). As the provider of analytic support for JRI efforts in Mecklenburg County, ARS was tasked with examining the arrest, jail, and other criminal justice data. ARS research staff sought and received from the Mecklenburg County Sheriff’s Office data on all arrests and jail releases for a four-year period from January 1, 2008 through December 31, 2011 for analysis. Data was also obtained from the North Carolina Administrative Office of the Courts, North Carolina Office of Indigent Services, and the National Center for State Courts. The CJAG focus groups and workgroup examined these and other findings in detail, and proposed a number of potential strategies to address these issues as well as the issue of citizeninitiated complaints. Potential strategies and objectives were developed by the workgroup and approved by the CJAG on March 5, 2013. Approved strategies include: increase the use of citations for low level offenses, decrease the volume of driving while license revoked cases, reduce the intake of mentally ill persons who are not a threat to public safety, provide short-term crisis intervention services and diversion options via a single service location, provide housing/shelter solutions coupled with proactive case management and social services for frequent service users, provide confidential screening and service-need assessments to offenders, coordinate community-based service delivery to targeted risk groups, establish a comprehensive offender reintegration framework for state prisoners released to Mecklenburg County, increase referrals to alternative dispute resolution settings, increase the use of summons when alternative dispute resolution is not appropriate and public safety is not impacted, and establish a citizen-initiated complaint docket. The Mecklenburg workgroup and CJAG are proactively using the data findings to more effectively utilize scarce correctional resources and to better respond to the needs of offenders. Mecklenburg County Jail data showed that there were 163,733 arrests between 2008 to 2011. These arrest episodes included 86,162 unique individuals with an average of 1.9 arrests during the time period. While bookings overall decreased each year in the study period, with the exception of 2008 to 2009, female bookings have seen a statistically significant increase. Key Finding #1: Low Level Offenses The top five offenses booked into the jail between 2008 and 2011 were: Driving While Impaired, Driving While License Revoked, Drug Paraphernalia – Possession of, Misdemeanor Possession of Marijuana and Assault on a Female – Non-Aggressive Physical Force. These low level offenses consume significant jail and court resources. Key Finding #2: Mental Illness/Homelessness (Frequent Jail Utilizers) A small group of offenders (referred to as frequent jail utilizers) account for a relatively large number of arrests and jail episodes, far out of proportion to their numbers. These offenders commit nuisance crimes and both previous research and anecdotal evidence suggest that they very likely have issues with mental illness, substance abuse, and homelessness. Data suggest that provision of mental health, substance abuse, and related social services within the community has the potential to reduce the demonstrated overutilization of criminal justice Dr. Kevin Baldwin Applied Research Services, Inc. 404-881-1120 ext. 104 www.ars-corp.com kbaldwin@ars-corp.com i CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts Kevin Baldwin, Ph.D. Applied Research Services, Inc. April 3, 2013 Background and Introduction The Justice Reinvestment Initiative (JRI) was launched by the United States Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) in 2006 in order to address the increase in corrections spending at both the state and local levels. Justice Reinvestment efforts are highly data-driven and are designed to reduce corrections spending without reducing public safety. Costs avoided through implementation of JRI strategies are reinvested into alternative criminal justice strategies that over the long term decrease crime and strengthen communities. These efforts rely on in-depth analysis of criminal justice data from a number of sources as a means of identifying the drivers of criminal justice costs, especially in the area of corrections. Once the major drivers are identified teams comprised of stakeholders in the criminal justice systems, aided by content experts under contract with BJA, closely examine the data and findings. Using their experience and insights from the data, the teams identify evidence-based approaches and policies aimed at addressing the identified drivers and assessing the potential impacts of proposed strategies designed to reduce costs and redirect funds to alternative strategies. The Justice Reinvestment Initiative (JRI) efforts in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina built upon and augmented the work of the preexisting Mecklenburg County Criminal Justice Advisory Group (CJAG). Oversight and coordination of the JRI efforts in Mecklenburg County was provided by Thomas Eberly, Criminal Justice Manager for Mecklenburg County. Training and Technical Assistance has been provided to Mecklenburg County by the Center for Effective Public Policy (CEPP) and Applied Research Services (ARS). As the provider of analytic support for JRI efforts in Mecklenburg County, ARS was tasked with examining the arrest, jail, and other criminal justice data, with the goals being to answer the following questions: Who is being arrested and why? Who is coming into the jail and why? How long are people staying in the jail? (by offender and offense characteristics) Why are people leaving the jail, and where they are going? What costs are associated with arrests, arrest processing, jail, court, and related areas? What cost impacts might be realized by implementing selected strategies? This report will detail the analytic efforts and findings of data analysis, placed within the context of Mecklenburg’s larger JRI efforts. 1 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. Methods Data Systems and Capacity for Research An initial analysis of data systems and research capacity in Mecklenburg’s criminal justice community was conducted in March, 2011, as part of their JRI Phase I application. At the time of this initial analysis two systems were in place to collect jail-related data, and they planned to install a web-based system in September, 2011. They used the Offender Management System (OMS) by Ciscon, which at that time had been in use for about ten years. They were also in the initial stages of implementing a justice system data warehouse (a SAP product known as Business Objects) designed to combine data across a number of agencies and disparate sources and scheduled to come online June, 2011 (full implantation was delayed a number of months, but is now fully operational). The OMS system has remained in place, as the new warehouse draws data from it and other systems. The seven local law enforcement agencies each have their own data system and are also part of the data warehouse network. The Sheriff’s Office has staff on hand who generate jail data reports, including quarterly reports which include trend analyses. They also send out daily population reports to key stakeholders, such as judges, the DA’s office, the sheriff’s office, and local chiefs of police. In addition, they can generate ad-hoc reports. The new warehouse system provides enhanced reporting functions and also allows the county manager’s office (for whom the county criminal justice manager works) to also generate reports. The data warehouse came about due to the lack of ability to look at trends and facilitate data driven decision making. A task force of concerned citizens was convened, and the work began on the warehouse in November, 2010. There exists a dashboard on the public website, where citizens can see information on a wide variety of criminal justice issues. The warehouse was populated going back to 2003, and allows for the examination of both individual and aggregate data. While the OMS system is capable of generating data extracts, the data warehouse has significantly expanded this capacity. The County Manager’s Office conducted a recidivism study a couple years ago on a random sample of jail inmates, but they had to rely on manual data collection (individual computer checks). They are confident about their ability to create data extracts with the warehouse and are excited about the potential to receive outside guidance on using more data to drive decision making. While they currently do not have the capacity to examine the length of time between critical events in the criminal justice continuum (data reside in multiple systems across agencies), the data warehouse is expected to allow for this in a comprehensive manner. Data is currently shared across agencies, and key players are reported to get along very well. The only reported data limitation is “Garbage In, Garbage Out” (e.g., 20 ways to spell Charlotte), which remains a challenge with the data warehouse. The county is reducing such occurrences by instituting self-completing fields and drop-down boxes to replace free-form data entry text fields. The single largest barrier at present is the city, county, and state agencies with various levels of data systems, each with different technological capacities. 2 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. Overall, the completion of Mecklenburg’s criminal justice data warehouse in June 2011 addresses perhaps the single most significant barrier in cross-systems criminal justice research – the inability of separate agency data systems to interface with one another. This, along with strategic thinking and good oversight from the Governor’s Information Technology committee and an apparent history of collaborative decision making and excellent local leadership, made Mecklenburg County an excellent candidate for Phase I JRI work. Data Gathering and Analysis ARS research staff sought and received from the Mecklenburg County Sheriff’s Office data on all arrests and jail releases for a four-year period from January 1, 2008 through December 31, 2011. While the arrest dataset included all arrests during this period, the jail extract contained information on all persons released during the specified time period, a dataset typically referred to as a release cohort. In addition to the arrest and jail data, we also sought and obtained the following data and resources: North Carolina Administrative Office of the Courts, Criminal Case Information Statistical Extract, a series of files concerning individual-level data on court cases and actions; North Carolina Office of Indigent Services, FY10 North Carolina Public Defender and Private Assigned Counsel Cost Analysis; North Carolina Office of Indigent Services, FY07 North Carolina Public Defender and Private Assigned Counsel Cost Analysis; North Carolina Office of Indigent Services, FY 11 Reclassification Impact Study; North Carolina Office of Indigent Services, North Carolina’s Criminal Justice System: A Comparison of Prosecution and Indigent Defense Resources; North Carolina Office of Indigent Services, Time Needed to Resolve Criminal Cases: A Comparison of Attorney Types; and National Center for State Courts, North Carolina Assistant District Attorney/Victim Witness Legal Assistant Workload Assessment: Final Report. The arrest and jail extracts contained selected fields (variables) of interest, and was organized such that each record represented a unique charge. For analytic purposes, the data was restructured such that each record represented a unique jail episode, and as a result each record could (and often did) contain more than one charge. The most serious charge in each episode was identified, and represents the charge of record for each unique arrest and jail episode. Once the data files were restructured, our next step was to work with the Sheriff’s IT staff to validate the arrest and jail data. This entailed performing a series of frequency counts and descriptive statistics to ensure that our data accurately reflected the numbers generated by the Sheriff’s office. 3 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. Findings Once the arrest and jail data had been validated, we began to perform statistical analyses in order to delineate the nature and characteristics of arrest and jail episodes and of the offenders themselves. The larger aim of the analyses was to identify the drivers of the arrest and jail populations, in order to identify potential areas where specific policy changes and/or strategies could be implemented to address JRI priorities. Trends in Arrests, 2008 - 2011 The Charlotte metropolitan area grew more rapidly during 2000 to 2010 than any other urbanized area with a population of 1 million or more, evidencing a growth rate of 64.6 percent during that decade. By way of comparison, the population growth rate in urbanized areas nationally was 14.3 percent (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). Despite this prodigious growth, arrests decreased from 2008 through 2011, as can be seen in Table 1, below. Table 1. Arrests by Year, 2008 – 2011. Year 2008 2009 2010 2011 Totals Number of Arrests 42,987 41,839 39,095 39,812 163,733 Percent 26.3 25.6 23.9 24.3 100.0 Cumulative Percent 26.3 51.8 75.7 100.0 A total of 86,162 individuals accounted for these arrest episodes, with an average of 1.9 arrests per arrestee over the four years from 2008 to 2011. Table 2, below, provides the racial/ethnic background of arrest episodes. Table 2. Race/Ethnicity of Arrest Episodes. Race/Ethnicity Black White Hispanic Other Total Frequency 103509 40660 17799 1765 163733 Percent 63.2% 24.8% 10.9% 1.1% 100% Regardless of how we categorize crimes, significant differences exist in regards to race/ethnicity. These differences however must be viewed in light of the overall representation of these racial/ethnic categories in the dataset as a whole, in which Blacks make up 63% of arrest episodes, Whites make up 25% of arrest episodes, and Hispanics make up 11% of episodes. With respect to their overall representation in the data, Blacks are less likely to be arrested for drug and traffic offenses than other 4 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. types of offenses, while Whites are more likely to be arrested for drug and traffic offenses than other types. Hispanics are more likely to be arrested for traffic offenses than they are for other types of offenses. Trends in Jail Bookings, 2008 - 2011 In addition to examining arrest trends, it is also critical to look closely at jail bookings and the characteristics of these episodes. Table 3, below, provides statistics regarding jail bookings for our 2008 through 2011 release cohort. Table 3. Jail Bookings and Releases, 2008 – 2011 Year 2007 and before 2008 2009 2010 2011 Total Bookings 2084 31868 34443 33615 31127 133137 Percent 2% 24% 26% 25% 23% 100% Releases NA 32041 34648 33821 32627 133137 Percent 0% 24% 26% 25% 25% 100% As with the arrest data, jail bookings decreased each year, with the exception of the increase from 2008 to 2009. The tables below provide data relative to the demographic characteristics of jail inmates for the fouryear period from 2008 through 2011. These data represent unique bookings rather than unique individuals, and therefore individual persons can and often do appear in the data more than once. Table 4. Race/Ethnicity of Jail Bookings, expressed as percent of total. Race/Ethnicity Black White Hispanic Other 2008 (%) 61.9 21.5 9.9 6.7 2009 (%) 61.8 21.9 10.0 6.3 2010 (%) 63.1 21.7 8.5 6.7 2011 (%) 63.2 22.4 7.5 6.9 Table 5. Gender of Jail Bookings, expressed as percent of total. Gender Male Female 2008 (%) 83.4 16.6 2009 (%) 83.0 17.0 2010 (%) 81.6 18.4 2011 (%) 81.2 18.8 As indicated in table 5, above, the percentage of female bookings into the jail has increased over the past four years. This change is statistically significant, and therefore may be of interest in terms of future programming and planning. 5 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. Regarding the types of crimes represented by bookings during this period, table 6, below, indicates the classification of the most serious offense at the time of booking, for releases during 2008 through 2011. Table 6. Crime Type of Jail Bookings, expressed as percent of total. Crime Type Misdemeanor Felony Traffic Total 2008 (%) 52.7 30.0 17.3 100.0 2009 (%) 53.2 28.0 18.7 100.0 2010 (%) 53.2 29.0 17.8 100.0 2011 (%) 52.5 29.4 18.1 100.0 As is apparent from the data in Table 6, above, the distribution of misdemeanors, felonies, and traffic offenses has remained quite stable over the past four years. We further coded offenses according to whether they represented person, property, drug, or other offense, with the results appearing in Table 7, below. Table 7. Crime class of Jail Bookings, expressed as percent of total. Crime Class Person Property Drug Other (inc. traffic) 2008 (%) 19.2 14.8 30.1 35.8 2009 (%) 19.3 15.0 27.4 38.2 2010 (%) 20.5 16.3 27.1 36.0 2011 (%) 21.8 16.3 26.5 35.8 The above data on crime type reveals a statistically significant difference in the representation of these categories over the past four years, with an increase in person offenses and a corresponding decrease in drug offenses. Property and other offenses remained relatively consistent over the time span. This trend suggests that the jail population is increasingly made up of violent offenders, reflecting national trends as well as citizens’ and policy makers’ preferences. In terms of number of charges per booking, 43.5%, 47%, 46.9%, and 48% of bookings represented only a single charge in the years 2008 through 2011, respectively. Ninety percent of jail bookings represented four or fewer charges. As would be expected, jail occupants are released for a number of reasons, with the most frequent being that pretrial offenders made bond and post-conviction offenders completed their sentence. The table on the next page provides the reasons for release of upwards of 95% of releases each year. 6 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. Table 8. Type of Release by Year, expressed as a percent. Type of Release Bond Satisfied Sentence Expired Other Jurisdiction Unsecured Dismissed Released on Probation/Parole Released per Court Pretrial Release Complied All others 2008 (%) 43.4 15.0 14.6 12.3 4.3 3.1 1.3 1.1 1.0 3.9 2009 (%) 45.0 12.9 13.0 16.6 3.6 2.4 1.4 0.7 0.9 3.5 2010 (%) 46.0 12.3 12.5 17.4 3.6 2.0 1.2 0.4 0.9 3.7 2011 (%) 44.6 13.2 12.7 16.3 3.7 2.0 0.9 0.6 1.0 5.0 In addition to the data in Table 8, above, it is important to note that only about 13% to 15% of releases were accounted for by transfer each year. Besides knowing why persons are released from jail, it is of course also critical to examine the reasons why people enter jail in the first place. Table 9, below, provides the top 25 charges (most serious charge only) for jail episodes, 2008 through 2011. Table 9. Top 25 Charges (Jail Episodes) 2008 – 2011. Charge (Most Serious Only) Frequency Percent 10740 8.1 Cumulative Percent 8.1 Driving While License Revoked 9285 7 15 Drug Paraphernalia - Possession Of 7014 5.3 20.3 Assault On A Female – Non-Agg. Phys. Force 5264 4 24.3 C/S-Sch. VI - Possess Marijuana – Misdemeanor 5196 3.9 28.2 Assault Or Simple Assault And Battery 4476 3.4 31.5 C/S-Sch. II - Possess Cocaine 3858 2.9 34.4 Assault On A Female - Agg. Phys. Force 3451 2.6 37 Resisting Public Officer 3426 2.6 39.6 Breaking and/or Entering (Felony)- With 3422 2.6 42.2 Trespass - 2nd Degree-Notified Not 3413 2.6 44.7 Larceny (Misdemeanor) - Under $50 2419 1.8 46.5 Larceny (Misdemeanor) - $50-199 2201 1.7 48.2 Intoxicated And Disruptive 2086 1.6 49.8 C/S-Sch. II - P/W/I/S/D Cocaine 2075 1.6 51.3 Larceny (Misdemeanor) - $200 & Up 2070 1.6 52.9 IV-D Non-Support Of Child 2064 1.6 54.4 No Operator's License 1875 1.4 55.8 C/S-Sch. VI - P/W/I/S/D Marijuana 1873 1.4 57.2 Fugitive/Extradition Other State 1787 1.3 58.6 Driving While Impaired 7 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. Communicating Threats 1448 1.1 59.7 Breaking and/or Entering (Misdemeanor) 1193 0.9 60.6 Probation Violation - Out Of County 1188 0.9 61.5 Probation Violation 1155 0.9 62.3 DV Protective Order Violation 1093 0.8 63.1 Table 10, below, provides the top five offenses (via the percent of all charges) responsible for people coming into the jail during the four year span between 2008 through 2011. Table 10. Top Five Offenses, 2008 – 2011. Offense (Literal) Driving While Impaired Driving While License Revoked Drug Paraphernalia – Possession of Possession of Marijuana, Misdemeanor Assault on a Female – Non-Aggressive Physical Force All others 2008 (%) 7.8 6.5 5.9 4.3 3.7 71.8 2009 (%) 7.8 7.5 5.3 4.1 3.7 71.7 2010 (%) 8.2 6.9 5.1 3.7 3.8 72.4 2011 (%) 8.5 7.1 4.8 3.6 4.7 71.3 The following data provide information on the Length of Stay (LOS) for jail episodes where these offenses represent the most serious offense, for the years 2008 through 2011. Table 11. Average LOS (ALOS) for the Top Five Offenses, 2008 – 2011. Offense (Literal) Driving While Impaired* Driving While License Revoked* Drug Paraphernalia – Possession of* Marijuana – Possession of (Misdemeanor)* Assault on a Female – Non-Aggressive Physical Force* Average Length of Stay (ALOS) 2008 2009 2010 2011 20.1 13.3 11.1 7.8 6.4 4.5 3.3 4.5 11.9 9.5 7.8 7.9 5.2 2.9 3.4 4.0 18.3 14.4 13.8 13.0 * Year-to-year decreases significant at the .05 level As is apparent from Table 11, above, the average length of stay for each of these offenses has decreased significantly over the past four years. These decreases are most significant for jail episodes due to DUI and Assault on a Female – Non-Aggressive Physical Force. Given the volume associated with these particular offenses, the decreasing ALOS suggests that these trends are certainly in the right direction, and should be sustained. The above data concerning the top five offenses, together with discussions among CJAG team members, the focus groups, and the working group, all suggested that taking a closer look at these relatively low level offenses likely presents opportunities to employ JRI strategies. Additionally, taking a closer look at the offenders who are most frequently arrested and jailed is also likely to present opportunities to bring JRI methods to achieve cost savings and cost avoidance strategies. 8 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. Key Findings of Interest Results of data analysis, along with subsequent review and discussion with CJAG members and the JRI workgroup, suggested that four key findings would be the focus of future JRI efforts, as follows: 1. 2. 3. 4. Low Level Offenses Mental Illness/Homelessness Recidivism Citizen Complaints The first three findings, and the data supporting each, are addressed in order in the following section. Key Finding 1: Low Level Offenses The results of data from the Arrest Processing Center, Jail, and the courts together indicated that a high percentage of arrests and jail episodes involved low-level offenses such as Driving While License Revoked (DWLR), Possession of Drug Paraphernalia, and Misdemeanor Possession of Marijuana. Averages for these offenses from 2008 – 2011 are as follows: o o o o DWLR: 3000 arrests; 2300 jail episodes Possession of Drug Paraphernalia: 2000 arrests; 1700 jail episodes Misdemeanor Possession of Marijuana: 1700 arrests and 1300 jail episodes By way of comparison, there were 41,000 annual arrests and 33,000 annual jail episodes We performed numerous analyses of arrest and jail data concerning “lower level” offenses, specifically certain misdemeanors and low level (H and I level offenses in North Carolina) felonies. These analyses focused on the volume of these cases and the local criminal justice resources expended to deal with them. What we found is that a relatively low number of lower level offenses dominate both arrest and jail episodes. For instance, in our 2008-2011 arrest cohort, there are 1162 unique charges listed as the most serious charge. Five of these offenses account for over 50% of arrest episodes. By contrast, 990 unique charges account for only 5% of arrest episodes. In addition to documenting the impact of lower level offenses on local criminal justice resources, it was also thought important to examine the degree to which these same offenses impact the courts. Data obtained from the North Carolina Administrative Office of the Courts (NC AOC) on traffic and non-traffic misdemeanor cases in Mecklenburg County were examined to document the impact of these offenses on the local courts. The data included the top 15 charges in descending order of cases filed between July 1, 2010 and June 30, 2011. The two tables on the next page provide data on traffic and non-traffic misdemeanor cases, respectively. 9 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. Table 12. Traffic Offenses. Charge (text) All Driving While Impaired DWLR Reckless Driving To Endanger Speeding No Operators License Hit/Run Fail Stop Prop Damage Reckless Drvg-Wanton Disregard Fail To Heed Light Or Siren Fict/Alt Title/Reg Card/Tag Drive After Consuming < 21 Flee/Elude Arrest W/Mv (M) Hit/Run Leave Scene Prop Dam Open Cont Aftr Cons Alc Subofn Fail To Stop For Stopped Bus Fictitious Info To Officer Cases Filed 900 319 163 69 64 58 35 30 17 16 16 16 10 9 8 8 Cases Pending 748 344 101 45 45 31 24 23 15 11 9 14 8 8 1 9 Cases Pending Median Days 175 212 140 157 177 160 140 160 120 107 125 248 250 119 98 351 Cases Disposed 721 149 159 65 63 56 23 24 23 22 11 11 7 15 8 12 Cases Disposed Median Days 168 221 166 191 136 135 140 239 170 157 141 105 119 369 103 340 Cases Pending Median Days 155 160 108 150 147 200 155 220 305 132 156 142 259 130 111 Cases Disposed 3,518 883 376 416 367 157 139 95 96 96 54 53 46 50 28 Cases Disposed Median Days 190 246 176 182 174 275 257 126 94 177 168 253 130 183 236 Table 13. Non-Traffic Misdemeanor Offenses. Charge (text) All Possess Drug Paraphernalia Misdemeanor Larceny Resisting Public Officer Possess Marijuana Up To 1/2 Oz Assault On A Female Carrying Concealed Gun(M) Communicating Threats Misd. Prob. Viol Out Of County Poss. Stolen Goods/Prop (M) Assault Govt. Official/Emply. Injury To Personal Property Assault With A Deadly Weapon Simple Assault DV Protective Order Viol (M) Cases Filed 3,295 777 394 366 285 168 128 106 94 80 75 65 52 46 33 Cases Pending 2,268 578 232 222 164 156 98 79 64 44 59 56 41 32 29 The above tables confirm that the same types of cases that dominate the arrest and jail rolls also consume significant court resources. In addition to costs borne by law enforcement, it is critical that costs of other components of the criminal justice continuum be considered in an attempt to quantify the fiscal considerations of JRI work. Costs of court personnel are therefore a necessary and substantial component of any examination of the price of adjudication. To that end, we also gathered data on 10 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. attorney time and costs, as well as administrative (non-attorney) court costs. Two sources of data were used for analyses involving attorney costs – a March, 2010 report by the National Center for State Courts (NCSC) entitled “North Carolina Assistant District Attorney/Victim Witness Legal Assistant Workload Assessment – Final Report” and a number of reports from the North Carolina Office of Indigent Counsel Services (NCIDS). Unfortunately these reports utilized different methodologies, and therefore the costs are not directly comparable. Nonetheless, they are illustrative of the significant costs associated with the prosecution and defense of crimes in North Carolina. In addition, administrative court costs were derived from the Court Costs and Fees Chart, January 2012 published by the North Carolina Administrative Office of the Courts. The table below provides data regarding the average number of minutes expended by attorneys per case type, taken from tables included in the NCSC report on state attorney workload assessment (The data for this report were compiled between 2008 and 2010). The number of minutes was multiplied by an hourly rate of $75, which is equivalent to the current hourly rate of Private Appointed Counsel (PAC) and Public Defenders in North Carolina. Table 14. Attorney Time per Case Type. Case Type Case Weight (Minutes) 6.5 Annual Filings 1,644,763 Cost per Case $8.13 Misdemeanor, other than DWI or Drug 19 373,781 $23.75 DWI 43 60,793 $53.75 Drug offense, other than trafficking 55 86,982 $68.75 Drug Trafficking 510 3,340 $637.50 Other Felony (F,G,H,I) 236 67,190 $295.00 Other Felony (A,B,C,D,E) 467 15,230 $583.75 Sex Crime 1,027 3,736 $1,283.75 Homicide, other than 1st Degree Murder 1,537 763 $1,921.25 10,073 446 $12,591.25 3,586 Unknown $4,482.50 Traffic 1st Degree Murder Generic Murder A March 2011 study by the North Carolina Office of Indigent Defense Services (NCIDS) analyzed all File Numbers disposed of in 2009, finding that Private Appointed Counsel (PAC) resolved cases more quickly than retained attorneys, needing on average two to six fewer weeks to resolve cases than retained attorneys. Public Defenders (PDs) resolved cases more quickly than both PAC and retained attorneys, resolving cases more rapidly than retained attorneys in 21 of 28 different case types and 19 of 28 different case types when compared to PAC. 11 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. A 2011 report by the NCIDS entitled “FY10 North Carolina Public Defender and Private Assigned Counsel Cost Analysis” provides the following costs per disposition in Mecklenburg County: Table 15. Costs per Disposition. Cost per Disposal District Expenditure PAC District Expenditure PAC State-wide Expenditure FY2008 $346 $498 $428 FY2010 $368 $498 $435 As would be expected, costs varied considerably based on the type of case and court venue. The following table provides PAC cost equivalents for FY 2010 PD Office Reported Dispositions, by type of case and court venue. Cost per case was derived by simply dividing district cost by the number of cases in the district (District N). Table 16. PAC Cost Equivalents, Mecklenburg County. Type of Case District N District Cost District Court Cost Per Case Superior N Felony A 0 0 0 Felony B 12 $10,928.00 $910.67 Felony C 17 $9,618.00 $565.76 Felony D 58 $27,180.00 $468.62 Felony E 35 $14,128.00 Felony F 32 Felony G Felony H Felony I Felony PV DWI* 0 Superior Cost Superior Court Cost Per Case 0 0 31 $56,423.00 $1,820.10 195 $230,321.00 $1,181.13 162 $174,349.00 $1,076.23 $403.66 52 $42,476.00 $816.85 $12,975.00 $405.47 92 $71,968.00 $782.26 106 $39,546.00 $373.08 229 $154,389.00 $674.19 564 $181,560.00 $321.91 566 $317,026.00 $560.12 525 $159,037.00 $302.93 350 $174,345.00 $498.13 158 $32,763.00 $207.36 1673 $387,978.00 $231.91 856 $266,725.00 $311.59 17 $10,292.00 $605.41 Misdemeanor Non-Traffic* Other Traffic* 8340 $1,903,857.00 $228.28 76 $33,260.00 $437.63 2750 $595,323.00 $216.48 28 $10,030.00 $358.21 Withdrawals 1187 $227,441.00 $ 191.61 309 $171,992.00 $556.61 * = Appeals in Superior Court As is apparent from the above tables, misdemeanors and level H and I felonies account for substantial expenditures relative to other categories of crimes. A Closer Look at DWLR Cases The preponderance of DWLR cases, as well as the corresponding resources consumed in adjudicating them, prompted the work group to take a closer look at DWLR cases in Mecklenburg County. Using the 2008-2011 arrest data, only cases for which the most serious charge was for Driving While License Revoked (DWLR) were included in the following series of analyses. 12 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. The following table provides a breakdown, by year and race/ethnicity, for all DWLR cases. The percentages represent the percent for each race/ethnicity within each year. Table 17. Race/Ethnicity for DWLR Cases. Race/Ethnicity 2008 2009 2010 2011 Black 70% 70% 71% 71% Hispanic 9% 10% 9% 9% White 20% 19% 19% 19% Other 1% 1% 1% 1% Totals 100% 100% 100% 100% There is no significant relationship between year of arrest and race/ethnicity with regard to DWLR offenders. When we examine gender however, there is a significant increase in the percentage of DWLR episodes involving females between the years 2008 and 2011, with females accounting for 17% of episodes in 2008 and 20% in 2011. This reflects a larger trend of females increasing involvement in arrest episodes in general over this same time period, a trend which has implications for correctional programming and planning efforts. None of the arrest episodes was indicated as having involved a probation violation, and it appears that the number of arrest episode for these DWLR offenders that involved more than one charge has decreased over the last four years, from 33% in 2008 to 27% in 2011. According to the North Carolina Office of Indigent Counsel Services, there are over 70 distinct reasons why a person’s driver’s license can be revoked. Data from the Department of Motor Vehicles is required to ascertain the reasons why members of the current arrest cohort had their driver’s licenses revoked. Such a process is beyond the scope of the current JRI work, put perhaps data from the District Attorney’s Office can at least indicate whether the revocation occurred due to a previous DUI, rather than non-payment of child support or any of the many other reasons for license revocations. Key Finding 2: Mental Illness/Homelessness (Frequent Jail Utilizers) A small group of offenders (referred to as frequent jail utilizers) account for a relatively large number of arrests and jail episodes, far out of proportion to their numbers. These offenders commit nuisance crimes and both previous research and anecdotal evidence suggest that they very likely have issues with mental illness, substance abuse, and homelessness. A total of 86,162 individuals (as indicated by the number of unique PIDs) accounted for all arrest episodes, with an average of 1.9 arrests per arrestee over the four years from 2008 to 2011. Looking at the top 1% of arrest episodes however, we find that 48 arrestees (.05%, or five one-hundredths of one percent) of all arrestees account for fully 1% of all arrest episodes (1704 total arrest episodes between them), an amount far out of proportion to their actual number. In terms of frequency of arrests, the top five individuals accounted for 70, 65, 62, 56, and 55 arrests over the four year span. Eighteen arrestees accounted for just under half (49.7%) of the 1704 total arrest episodes for this entire group of 48 arrestees. 13 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. When examining the charges brought against this group of arrestees (counting the most serious charge only), the offenses are overwhelmingly misdemeanor in nature (93%), followed by felony (4.4%) and traffic (2.6%) offenses. Table 18, below, provides the 15 most common charges for this group, which together account for three-quarters of all charges. Table 18. Charges for Frequent Jail Utilizers (listing most serious charge per arrest episode only). Charge Trespass - Second Degree – Notified Not to Enter Solicit Alms/Beg for Money Drug Paraphernalia – Possession of Intoxicated and Disruptive Larceny (Misdemeanor) – Under $50 Larceny (Misdemeanor) - $50 - $199 Soliciting from the Street or Median Resisting Public Officer Alcoholic Bev. – Consume Wine/Beer on Public Street Probation Violation Driving While License Revoked Larceny (Misdemeanor) - $200 and up Open Container Ordinance Alcoholic Bev. – Public Consumption C/S – SCH II – Possession of Cocaine 113 other charges Number Percent 302 199 147 133 110 57 53 48 46 36 35 34 34 29 28 17.7 11.7 8.6 7.8 6.4 3.3 3.1 2.8 2.7 2.1 2.0 2.0 2.0 1.7 1.6 24.4 Cumulative Percent 17.7 29.3 37.9 45.7 52.2 55.5 58.6 61.4 64.1 66.2 68.3 70.3 72.2 73.9 75.6 100.0 These arrestees were predominantly African American (69%) and male (98%). Sixty-one percent of arrestees had only one charge for the arrest episode of record, while 23.6% had two charges, 8.5% had three charges, and 3.7% had four charges. In terms of arrest type, close to three quarters (72.2%) were the result of a visual arrest (code ORD), 21.4% were due to the issuance of an Order for Arrest (OFA), and 6.4% were the result of an arrest warrant being issued. Regarding the type of bond issued, secured bonds were indicated in 96.4% of arrest episodes, with no bond issued (code: NBD) at 1.3% and 1% as missing. A third of arrest episodes had a bond amount of $500, with 12% each having bond amounts of $1000 and $250. After removing the missing cases, 1092 out of 1657 arrest episodes, or 66%, had bond amounts of $500 or less. The vast majority (93.2%) of arrest episodes have no bond release information, with 2.8% receiving a secured bond, 2.3% an unsecured bond, and 1% released via a Written Promise to Appear (code WPA). Likely due to their status as frequent arrestees as well as other characteristics, 94% of the arrest episodes for this group also involved a jail stay. As such, this group of 48 persons had a combined total of 1601 jail episodes between 2008 and 2011, for a total of 21,445 bed days. Table 19, below, provides the total number of bed days for this group for each year from 2008 – 2011, as well as the total cost of these bed days using cost figures provided by the jail. 14 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. Table 19. Bed days consumed by the 48 most frequent users of the jail, 2008 – 2011. Year 2008 2009 2010 2011 Total (Avg.) Total Bed Days 4715 5488 5664 5578 21445 Cost per Day (average) $102.15 $110.05 $124.73 $131.04 ($116.99) Total Cost $ 481,637.25 $ 603,954.40 $ 706,470.72 $ 730,941.12 $ 2,508,850.55 As is apparent from the data above, this group of 48 persons accounted for 1704 arrests and 1601 jail episodes over a four year period. The jail episodes resulted in a total of 21,445 bed days, for a cost of over $2.5 million dollars. These costs are considerable, and do not include the cost borne by the arresting agencies or the cost of processing them in the Arrest Processing Center and Jail. Taken together, it would appear that a relatively large number of arrests concern a very small number of persons, in that five one hundredths of one percent (.05%) of arrestees accounted for 1% of all arrest episodes during the four years between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2011. Fully 94% of these arrests were followed by a jail episode, at the cost of just over $2.5 million dollars in bed days alone. These persons were most likely to be arrested for minor crimes, often referred to as public order or public nuisance offenses, such as begging, trespassing, and public alcohol use and/or intoxication. This pattern of offenses is suggestive of a typical problem concerning offenses committed by persons afflicted with mental illness and or substance abuse issues, and who are also likely to be homeless. In terms of next steps, these data suggest that provision of mental health, substance abuse, and related social services within the community has the potential to reduce the demonstrated overutilization of criminal justice resources by this small group of persons. One possible means of addressing these offenders, many of whom are likely to be suffering from mental illness, would be to have officers who have received Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training respond to these arrest situations. Doing so may result in transport of the potential arrestee to a mental health or social services facility and correspondingly reduce the likelihood that some of these situations result in an arrest. Such diversions save public funds and allow officers to devote their time to relatively more serious offenses and offenders. They also have the potential to address the underlying issues presented by these individuals, potentially reducing their likelihood of future arrest and incarceration. These data, and the conclusions derived from them, closely mirror the findings of a study of chronic offenders published in March, 2007 by the Mecklenburg County Sheriff’s Office.1 1 Eberly, T.A., Takahashi, Y., & Messina, M. (2007). Chronic Offender Study: Final Report. Charlotte, NC: Mecklenburg County Sheriff’s Office, Research and Planning Unit. 15 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. Key Finding 3: Recidivists A large percentage of offenders recidivate, after having been released either from the jail or to Mecklenburg County from North Carolina prisons. Recidivists look very similar to non-recidivists in terms of their personal and offense characteristics. Hope L. Marshall, MS, LCAS, Enterprise Management Analyst for Criminal Justice Services in the Mecklenburg County Manager’s Office, drew a random sample of 400 North Carolina prison inmates who were released to Mecklenburg County, checking for the presence of a re-arrest in the two years following their release. The resulting dataset included those former inmates (N = 184, or 46% of the total sample of prison releases) who were arrested in Mecklenburg County during the two-year followup period. The data included their OTIS number (a prison identification number), their PID (the local identification number used to identify arrestees and jail inmates in Mecklenburg County), arrest date and arrest number. If they were arrested a second time during the same two-year follow-up period, that information was also included. This data, which included data from 2012, was merged with the four-year arrest cohort (arrests 2008 through 2011) used in Mecklenburg’s Justice Reinvestment Initiative efforts to date, and described in depth in previous sections of this report. This arrest dataset, rather than containing one record per person as is the case with the data provided by Ms. Marshall, contains a separate record for each arrest episode. Given that each record represents a single arrest, each record also includes all charges brought at the time of the arrest, and is keyed off the most serious charge at the time of arrest. As noted above, 184 (46%) of the random sample of 400 prisoners released from North Carolina prisons to Mecklenburg County had at least one arrest in the two years following their release. A total of 119 (30%) had two arrests within the follow-up period, while 75 (19%) had three or more arrests. Using the PID field common to the two datasets, 170 of the 184 members of the prison release cohort were identified in the 2008 – 2011 arrest cohort. During the four years encompassed by the arrest cohort, the average number of arrests for this sample of recidivists was 6 (range from 1 to 38), with a median of 4 and a mode of 6. Twenty-two of the members of the sample had only one arrest in the 2008 – 2011 dataset, due to the inclusion of 2012 arrest data in Ms. Marshall’s sample. Just under nine-in-ten arrest episodes (89.3%) involved African American arrestees, with 6.1% involving Caucasians and 4% involving Asians. Ninety-eight percent of arrests for this group represented males. An examination of the crime classifications (most serious offense) involved in these arrest episodes can be seen in Table 20. 16 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. Table 20. Crime Classification. Crime Classification Felony Misdemeanor Traffic Total Missing Total Frequency 472 435 58 965 2 967 Percent 48.8 45 6 99.8 0.2 100 Valid Percent 48.9 45.1 6 100 Cumulative Percent 48.9 94 100 The types of crimes (most serious offense) involved in these arrest episodes can be seen in Table 21, below. Table 21. Crime Type. Crime Type Person Property Drug Other Total Missing Total Frequency Percent 147 190 225 403 965 2 967 15.2 19.6 23.3 41.7 99.8 0.2 100 Valid Percent Cumulative Percent 15.2 19.7 23.3 41.8 100 15.2 34.9 58.2 100 As can be seen in the tables above, about half of arrest episodes involve a misdemeanor, and 43% involved a drug or property offense as the most serious charge. As might be expected, a number of the arrest episodes involved either a probation or parole violation. In fact slightly more than one-in-ten (11.7%) did, with the violation being listed as the most serious charge in the vast majority (91%) of these cases (see Table 22, below). Table 22. Arrest Episode Includes a Probation/Parole Violation. Episode Includes a Probation/Parole Violation No Yes Total Missing Total 17 Frequency 852 113 965 2 967 Percent 88.1 11.7 99.8 0.2 100 Valid Percent 88.3 11.7 100 Cumulative Percent 88.3 100 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. As previously indicated, each record in the 2008 – 2011 arrest cohort represents a single arrest episode which can, and often does contain more than one charge brought at the time of arrest. Table 23, below, provides the number of charges per arrest episode for this sample of released prison inmates. Table 23. Number of Charges per Arrest Episode. # of Charges at this Arrest Episode 1 2 3 4 5 6 or more Total Frequency 397 180 128 125 40 97 967 Percent 41.1 18.6 13.2 12.9 4.1 10.0 100 Cumulative Percent 41.1 59.7 72.9 85.8 90 100 As can be seen in the above table, 60% and 90% of arrest episodes for this sample included two and five charges or less, respectively. The top 25 specific charges involved in the arrest episodes for this sample can be found in Table 24, below. Table 24. Top 25 Charges (Charge Literal), Most Serious Charge at Arrest Episode. Rank Charge Literal 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Probation Violation Drug Paraphernalia - Possession Of Trespass - Second Degree - Notified Not To Enter Breaking and/or Entering (Felony)- With Force Driving While License Revoked C/S-Sch. VI - Possess Marijuana - Misdemeanor C/S-Sch. II - Possess Cocaine Resisting Public Officer C/S-Sch. II - P/W/I/S/D Cocaine Assault On A Female – Non-Agg. Phys. Force Bond Termination C/S-Sch. VI - P/W/I/S/D Marijuana Assault On A Female - Agg. Phys. Force Possession Of Firearm By Felon Consp. Robbery Dangerous Weapon Larceny (Misdemeanor) - Under $50 Parole Violation Communicating Threats Larceny (Misdemeanor) - $50-199 Break/Enter Motor Vehicle - $200 & Up 18 Frequency Percent 90 63 61 51 39 37 30 30 26 24 24 17 14 14 13 13 13 12 12 11 9.3 6.5 6.3 5.3 4 3.8 3.1 3.1 2.7 2.5 2.5 1.8 1.4 1.4 1.3 1.3 1.3 1.2 1.2 1.1 Cumulative Percent 9.3 15.8 22.1 27.4 31.4 35.3 38.4 41.5 44.2 46.6 49.1 50.9 52.3 53.8 55.1 56.5 57.8 59 60.3 61.4 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. Rank Charge Literal 21 22 23 24 25 26-155 Larceny (Misdemeanor) - $200 & Up Robbery With Dangerous Weapon - Individual (Felony) Probation Violation - Out Of County Assault Govt. Official/Emply – Non-Agg. Phys. Breaking and/or Entering (Felony)-Without Force All other charges (N = 130 other separate charges) Frequency Percent 11 11 10 9 9 967 1.1 1.1 1 0.9 0.9 33.4 Cumulative Percent 62.6 63.7 64.7 65.7 66.6 100 As can be seen in Table 5 (above), the top 25 charges account for 67% of all arrest episodes for this sample of prison inmates released to Mecklenburg County. Eleven charges account for fully half of all arrest episodes for this sample. As regards the Mecklenburg County Justice Reinvestment Initiative (JRI) efforts, four of the top six charges (representing 21.6% of this sample’s arrest episodes) are included among those selected for consideration as part of the proposed JRI strategies. About half of the arrest episodes involved misdemeanors, and about 12% involved either a probation or parole violation. Only about 15% represented an offense against another person or persons. Conclusions Regarding Recidivism An analysis of recidivism extended the findings of a separate analysis conducted by the County Manager’s Office involving a random sample of 400 inmates released from North Carolina prisons to Mecklenburg County and followed through 2012. Slightly less than half (46%) of the total random sample of 400 prisoners released from North Carolina prisons to Mecklenburg County had at least one arrest in the two years following their release. A total of 119 (30%) had two arrests within the follow-up period, while 75 (19%) had three or more arrests. This sample of 184 recidivists was merged with a separate dataset containing all arrests in Mecklenburg County from 2008 through 2011. A total of 170 of the 184 members of the prison release cohort were identified in the 2008 – 2011 arrest dataset. During the four years encompassed by the arrest cohort, the average number of arrests for this sample of recidivists was 6 (range from 1 to 38), with a median of 4 and a mode of 6. As such, this group of 170 represented 967 separate arrest episodes over a four-year period. Given that four of the top six charges listed as the most serious offense involved in these arrests was for charges already identified as potential JRI strategies, it stands to reason that effecting strategies designed to address these charges would impact both recidivist former prison inmates as well as potential arrestees in general. Given the proportion of these episodes which involved a probation or parole violation (12%), any reduction in arrests for these charges would be felt most acutely in a reduction in jail bed days, given the relatively high proportion of bed days consumed by probation/parole violators. 19 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. Cost Impact Projections Our next step was to attempt to identify potential cost impacts associated with proposed policies designed to address the focus areas delineated above. We utilized the numbers of arrests and jail episodes from 2008 through 2011, as well as the length of stay data associated with a number of specific offenses, to calculate cost projections for the strategy targets. The event data used for these projections was the arrest and jail data described earlier. We obtained and/or calculated both average costs (the total budget divided by the total number of events) and marginal costs (the costs associated with adding a single event) for the low level offenses and frequent jail utilizers. We included the following types of costs: arrest costs arrest processing costs jail bed costs court processing costs public defense costs prosecution costs We began by calculating baseline cost projections, which projected cost impacts if no new strategies or policies were implemented. Then we projected 10% and 20% reductions in arrests and/or jail episodes and calculated out the cost impact projections for two and four years after implementing the potential strategies. The projections suggest that potential costs impacts, in decreasing order, would be realized by addressing the following issues: DWLR Possession of Drug Paraphernalia Misdemeanor Possession of Marijuana Frequent Jail Utilizers (based on limited sample of 48) Should the suggested strategies be implemented and result in a 10% reduction in service demand, projections using marginal costs suggest that a cost impact of approximately $5.4 million could be realized over a four-year period. These cost projections are conservative, and it is likely that more longterm cost avoidance figures would be realized as well. The detailed results of these projections can be found in Appendix A. Proposed Strategies The CJAG focus groups and workgroup examined these and other findings in detail, and proposed a number of potential strategies to address these issues as well as the issue of citizen-initiated complaints. 20 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. The following potential strategies and objectives were developed by the workgroup and approved by the CJAG on March 5, 2013: Finding Low Level Offenses Strategies Increase use of citations for low level offenses Decrease the volume of driving while license revoked cases Mental Illness/Homeless Reduce the intake of mentally ill persons who are not a threat to public safety Provide short-term crisis intervention services and diversion options via a single service location Provide housing/shelter solutions coupled with proactive case management and social services for frequent service users Provide confidential screening and service-need assessments to offenders Recidivism Citizen-initiated Complaints Coordinate community-based service delivery to targeted risk groups Establish a comprehensive offender reintegration framework for state prisoners released to Mecklenburg County Increase referrals to alternative dispute resolution (ADR) settings Objectives Implement low-level arrest proxy tool and training Add low-level arrest trend report to CJAG agenda Formalize DWLR alternatives to arrest policy Add DWLR trend report to CJAG agenda Implement driver’s license restoration clinic Reduce or delay “automatic” loss of driver’s license for non-safety reasons Formalize protocol for strategic deployment of CIT officers Institute continuing education and annual certifications standards for CIT officers Create community-based mental health crisis center Formalize protocol for utilization of crisis center by law enforcement Implement supportive housing pilot project Evaluate supportive housing pilot outcomes and cost savings Expand pilot project if successful Implement offender screening and assessment policy Implement offender screening and assessment program Initiate presentence reports for felony defendants Complete offender service-need audit Complete community resource/service audit Complete service integration plan Formalize prisoner re-entry plan Launch community resource center Launch residential re-entry center Increase the use of summons when alternative dispute resolution is not appropriate and public safety is not impacted Establish a citizen-initiated complaint docket 21 Conduct ADR advocacy training for law enforcement and magistrates Explore the use of community courts in targeted neighborhoods as ADR settings Implement a warrant/summons issuance tracking system Include warrant/summons issuance trend report on CJAG agenda Establish a citizen-initiated complaint docket CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. Next Steps Establish mechanisms to effect proposed strategies detailed above, ensuring buy-in and collaboration among participating agencies Establish a means of tracking above objectives using measurable indicators, so as to document progress towards strategy implementation. Ensure that the means of tracking, and the corresponding data regarding progress towards strategy implementation and achievement of objectives, is operationalized and available to all stakeholders. This would likely best be accomplished by having the means of tracking and reporting available through the county criminal justice warehouse and Internet-based reporting system. Select appropriate strategies for potential JRI Phase II funding, and make application for said funding. 22 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc. Appendix A. Projected Cost Impacts. Summary of Projected Potential Cost Impacts Projected Savings Targets - in decreasing order of potential savings Marginal Costs Order Offense 2 Year Projected 4 Year Projected Average Costs 2 Year Projected 4 Year Projected 1 DWLR Arrrest and Jail Total Baseline -$211,259.54 -$673,277.85 -$203,955.30 -$651,542.14 10% reduction $729,594.28 $1,543,765.90 $910,682.32 $1,903,020.24 20% reduction $2,830,825.79 $5,989,811.69 $3,533,447.39 $7,383,718.52 Net 10% $940,853.81 $2,217,043.75 $1,114,637.61 $2,554,562.38 Net 20% $3,042,085.33 $6,663,089.54 $3,737,402.69 $8,035,260.66 Baseline -$263,801.76 -$838,917.20 -$256,497.52 -$817,181.48 10% reduction $934,759.13 $1,975,125.01 $1,115,847.17 $2,334,379.35 20% reduction $3,626,865.43 $7,663,485.03 $4,329,487.03 $9,057,391.86 Net 10% $1,198,560.89 $2,814,042.20 $1,372,344.69 $3,151,560.83 Net 20% $3,890,667.19 $8,502,402.23 $4,585,984.54 $9,874,573.35 Marginal Costs Order Offense 2 Year Projected 4 Year Projected Average Costs 2 Year Projected 4 Year Projected 2 Poss. Drug Para. Arrrest and Jail Baseline $33,233.76 $88,414.95 $146,461.95 $383,101.87 10% reduction $438,677.21 $863,997.48 $614,862.01 $1,170,822.11 20% reduction $1,702,067.56 $3,352,310.23 $2,385,664.58 $4,542,789.80 Marginal Costs Order Offense 2 Year Projected 4 Year Projected Total Baseline 4 Year Projected $77,045.66 $210,864.82 $190,273.85 $505,551.74 10% reduction $568,565.01 $1,106,225.25 $744,749.81 $1,413,049.88 20% reduction $2,206,032.24 $4,292,153.95 $2,889,629.26 $5,482,633.53 Marginal Costs Order Average Costs 2 Year Projected Offense 2 Year Projected 4 Year Projected Average Costs 2 Year Projected 4 Year Projected 3 Poss. Marijuana (M) Arrrest and Jail Total Baseline $27,639.17 $63,706.35 $53,944.70 10% reduction $340,705.27 $670,347.90 $398,818.64 $776,026.03 20% reduction $1,321,936.43 $2,600,949.85 $1,547,416.33 $3,010,981.01 $206,419.20 Baseline $52,557.00 $134,784.46 $78,862.53 10% reduction $442,999.50 $864,962.69 $501,112.88 $970,640.82 20% reduction $1,718,838.08 $3,356,055.23 $1,944,317.97 $3,766,086.39 Marginal Costs Order $135,341.09 Offense 2 Year Projected 4 Year Projected Average Costs 2 Year Projected 4 Year Projected 4 Frequent Fliers Arrrest and Jail Total Baseline -$16,037.55 -$53,130.50 -$80,187.76 10% reduction $30,332.24 $67,094.33 $151,661.18 $335,471.63 20% reduction $117,689.08 $260,325.98 $588,445.39 $1,301,629.91 Net 10% $46,369.79 $120,224.83 $231,848.95 $601,124.13 Net 20% $133,726.63 $313,456.48 $668,633.15 $1,567,282.41 Baseline -$41,265.68 -$134,235.91 -$105,415.89 -$346,757.91 10% reduction $152,135.51 $320,801.76 $273,464.45 $589,179.06 20% reduction $590,285.76 $1,244,710.81 $1,061,042.07 $2,286,014.74 Net 10% $193,401.19 $455,037.66 $378,880.34 $935,936.96 Net 20% $631,551.44 $1,378,946.72 $1,166,457.97 $2,632,772.64 Marginal Costs Order Offense 2 Year Projected 4 Year Projected -$265,652.50 Average Costs 2 Year Projected 4 Year Projected 5 NOL Arrrest and Jail Total Baseline $31,605.64 $85,168.48 $55,876.40 $142,087.49 10% reduction $75,884.65 $139,066.41 $99,547.26 $176,504.66 20% reduction $294,432.44 $539,577.67 $386,243.37 $684,838.08 Baseline $44,370.35 $118,005.67 $68,641.10 $174,924.69 10% reduction $94,119.38 $170,682.80 $117,781.99 $208,121.05 20% reduction $365,183.18 $662,249.26 $456,994.12 $807,509.67 Figures in red text indicate costs, rather than savings. Four-year trends for DWLR and Frequent Fliers are such that the baseline represents additional costs incurred. For these categories, the 10% and 20% net figures represent the difference between the costs at baseline and the savings at 10% and 20%. 23 CEPP-JRI Mecklenburg: Summary of Phase I Data Analysis Efforts – Applied Research Services, Inc.