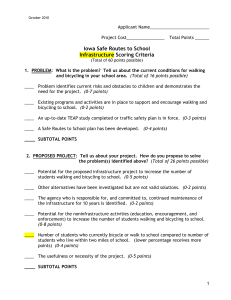

Healthy Places, Healthy People Promoting Public Health & Physical Activity

advertisement