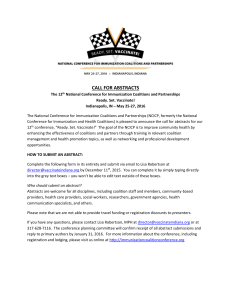

& Arts Organizations Public Health Partners for Livable Communities

advertisement