Why Mortgagors Can’t Get No Satisfaction I. I

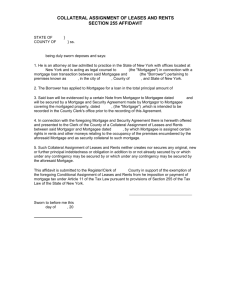

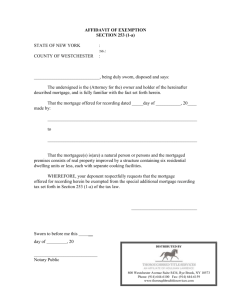

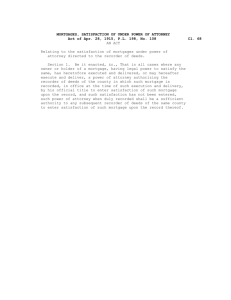

advertisement