Adrian Borbély & Julien Ohana, The Impact of the Negotiator’s... Dimensions, in Negotiation Desk Reference (Christopher Honeyman & Andrea

advertisement

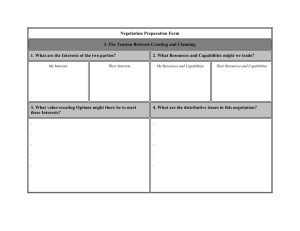

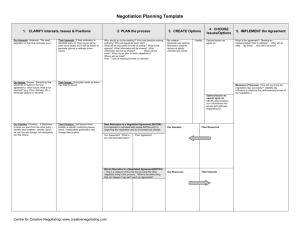

Adrian Borbély & Julien Ohana, The Impact of the Negotiator’s Mindset in Three Dimensions, in Negotiation Desk Reference (Christopher Honeyman & Andrea Schneider eds., forthcoming). Draft – Please do not quote or cite without permission. Beyond skills, such as preparing and strategizing, questioning and listening, dealing with different cultures, etc., how do we explain how negotiations unfold? Some of us use a process approach, detailing different steps that one needs to follow (not necessarily in a linear manner). This approach is controversial: some consider it oversimplifies what happens in the real world of negotiations; yet, others, like us, claim it should not be completely ignored, as it offers negotiators a roadmap – granted, simplistic – to better understand the path they engage in. This chapter does not aim to offer a process approach, but will rely on one to pool together two ideas that we are transmitting to our students during their training, in order to help them grasp how negotiation functions. First, and often contrary to their original belief, negotiation is not only about what is being negotiated (substance) but also about who negotiates (people) and how to do so (process). The three-dimension model is useful, as it helps students put into perspective the substance of their negotiation and integrate the two other elements in their negotiation preparation, practice and analysis. Second, we do not portray the distributive and integrative models as elements drawn from the context, but as two possible mindsets that negotiators may hold, which will impact their behavior on each of the three dimensions. These two ideas taken together enable us to isolate and classify a series of behaviors frequently observed at the negotiation table. 1 The Three Dimensions of Negotiation Whether explicitly or not, negotiation teaching manuals often introduce negotiation as a combination of three dimensions: the relationship, process, and substance aspects (e.g. Mnookin, Peppet and Tulumello 2000). This categorization aims to remind students that negotiation should not be approached exclusively from the substance angle, that is, a focus solely on resolving the problem at hand. From preparation on, negotiators are encouraged not to hasten towards their arguments, counter-arguments and possible solutions, but to include two additional elements into their thought process: whom am I negotiating with, and how should we proceed? After all, negotiation is an interpersonal communication process; it is therefore essential to study the different legs of the voyage, from departure to arrival, as well as existing or potential relations between its participants. We must specify what these dimensions entail. The substance dimension concerns the object of the negotiation, the roots of the issue (the contract to be established, or the conflict to be resolved), and all the elements that allow us to assess it. The object of the negotiation is defined by the parties themselves, sometimes through another, strategic negotiation. It is composed partly of what parties request (positions) but also of the parties’ history, needs, values, preoccupations and worries (interests), as well as what has caused the situation (origins). On the substance dimension, people need to think about a field of possible solutions that takes into account their constraints, especially their alternatives to a negotiated agreement (Fisher and Ury, 1981). 2 The relationship dimension focuses on the choice of partners in a negotiation, what we know about them and their position in their organization (expertise, autonomy, authority, etc.), what connects or divides us (shared history and/or past disputes), as well as the affective aspects of our ties (trust [Lewicki], emotions and identity). Relationship aspects can also reveal possible coalitions for participants, at the table but also beyond the table, with un-invited stakeholders (people interested in the outcome or with the capacity to block its implementation, though neither present nor represented at the negotiation). [Wade, Tribe] The process dimension covers the elements that structure the negotiation; it goes beyond just the “shape of the table” and ground rules. One may approach this architecture through the prism of the “6P’s” (Lempereur, Colson and Pekar 2010): The Project (reason and purpose of the meeting); Planning (agenda and timing); People (roles and representation); Procedures (rules for communication, adjournment, etc.); Place (logistical aspects); and Product (type of deliverables and commitment). Negotiators need to understand the three dimensions, first, to recognize that all three are negotiable. During a negotiation, in addition to negotiating on the substance, people share the responsibility to create an efficient, adaptive process and to manage a relationship-friendly atmosphere – provided that it fits with their objectives, of course. In themselves, these elements may lead to more-or-less visible preliminary negotiations. Second, negotiators must distinguish these three dimensions in order to adapt their behavior at the table. Indeed, does the other party’s action call for a response on the substance (a counter-argument, or a counter-offer)? Or would it, on the contrary, be wiser to respond through a relationship gesture (e.g. improve relationships through an informal 3 meeting), or a process one (for example, a reminder of the rules or the purpose of the meeting)? The three dimensions should therefore be used as the trunk of the decision tree before people take any action in a negotiation. Articulating the Three Dimensions The three dimensions are linked and interdependent; they should therefore not be distinguished for purposes of taking them apart, but to clarify how they add to one another. While the relationship dimension can function autonomously (people can be connected without going into a formal negotiation process), the other two cannot. The process dimension necessarily relies on the relationship, as there can be no process without interconnected parties (even if they are bound by an unproductive relationship.) Likewise, the substance dimension relies on the other two: we cannot discuss a matter without a process (however informal), nor without a relationship among the parties (however bad). It is therefore just as important to distinguish the roots of the different elements of the negotiation (particularly the parties’ actions) as it is to acknowledge the entanglement of the negotiation’s constituent dimensions. We therefore propose a principle of addition of the three dimensions. The following diagram illustrates this principle throughout a negotiation session. 4 We designed this graph to suggest that it makes sense not only to segment (vertically), but also to sequence (horizontally) the three dimensions. Even if this may not be palpable in a simple negotiation, it could turn out to be fundamental for more complex situations. Indeed, the previous diagram shows that the negotiation curve goes through five main stages of negotiation: Relationship Process Substance Process Relationship It is worth emphasizing that sequencing does not imply linearity, quite the opposite: negotiators may often have to go back and forth between substance, process and relationship. In practice, the curve may look like a rollercoaster, going up and down between the different dimensions, depending on the evolution of the discussion on the different points at hand. (It may also feel that way to the participants.) In other words, negotiation is not about aligning the stages into a unique path, but rather about navigating them in a way that makes searching for an agreement as efficient as possible. 5 Our approach enables us to show apprentice negotiators how to start their negotiation. Often, at the beginning, they may feel frustrated, as they are impatient to start working on the substance and building their agreement. We tell them it would be unwise to bypass what we consider to be two mandatory stages. First, addressing the relationship issues upstream helps create a favorable working environment. Then, discussing process serves to set the rules and logistics for communication; these elements may themselves be subject to a negotiation (Fisher and Ury 1981). Beyond the immediate effects this may have on the conversation on the substance, negotiators who neglect these early stages deprive themselves of a safety net in case the situation becomes difficult. When discussions become tense, particularly when approaching a stalemate, negotiators must be able to lean back on their early work on the rules of the game (reiterating them if necessary), or the strength of their relationships through, for example, a friendly break. Downstream, when closing a negotiation session, spending time on the process will serve to set the conditions for decision-making and the implementation of the agreement. So many negotiators fail to secure these elements and see good substantive deals fail in their implementation phase! Finishing with a relationship touch will strengthen and maintain the negotiators’ relationship for future negotiations. In other words, at the end, when a partial or full agreement is reached, negotiators must be able to capitalize on their relationship for future exchanges, which may in itself help implementation. [Wade & Honeyman, Lasting Agreement] Adding the three dimensions could therefore serve as a framework for teaching a simple conception of a negotiation process, keeping in mind that negotiators will need to adapt it to suit their own practice. Again, this should not be presented as a cooking recipe, 6 in which steps need to be followed in order; rather, as a map, with many different paths to explore. Negotiation as a Mindset Question Negotiation theories distinguish between two approaches or even two categories of negotiations: integrative and distributive. This distinction is particularly well explained by Roy Lewicki and his colleagues (2014). On the one hand, the principle of distributive negotiation is to divide a fixed and limited set of resources between parties with diametrically opposed objectives. For example, in a commercial negotiation, the buyer will aim for a low price, while the seller aims for a high price. Based on the presupposition that one’s gain is another’s loss, negotiation is seen as a confrontation where parties exchange offers and counteroffers, trying to convince their counterpart of the strength of their position. In such a setting, negotiators may be tempted to use tactics that are more or less aggressive, even ethically questionable. Integrative negotiation, on the other hand, brings negotiators to acknowledge the value that may be created through a cleverly constructed agreement that takes into account multiple dimensions, on which the parties’ objectives may not necessarily be incompatible. Even if they were totally incompatible, it recognizes that agreeing to disagree, as it preserves the relationship, is preferable to a rupture in communication. As one party’s gain is not necessarily the other’s loss, negotiators face a common problem, and can generate additional resources through “creative cooperation” (Halifa and Cantournet 2011). 7 Distributive negotiation generally focuses on a single variable (usually money) and is founded on extrinsic interests (the carrot and the stick). Conversely, integrative negotiation requires multiplying the dimensions of the discussion; it often puts more focus on extrinsic motors (motivations and meaning) in order to generate “win-win” discussions among parties. Some may perceive a negotiation setting as either integrative or distributive. In this case, buying a second-hand car, or a piece of real estate, would be purely distributive negotiations, as these settings focus mostly on price, with little-to-no long-term or relationship aspects. Some see all negotiations as an alternation between distributive and integrative phases. Negotiators would therefore have to switch strategies, depending on how the negotiation unfolds, i.e. whether they are in a value creation or distribution phase. We prefer to define the “distributive-integrative” distinction according to how negotiators perceive and approach the negotiation, in other words through the negotiators’ mindset. By “mindset” we mean the lens, or in other words the set of assumptions, through which negotiators define a negotiation situation (Pinkley and Northcraft 1995). This allows acknowledging that any negotiation situation can have both distributive and integrative aspects: it will become either distributive or integrative according to how its participants choose to deal with it. This is particularly visible in dispute resolution: some see the dispute as purely distributive, a view often supported by the judicial system (and legal counsels), who function based on one party defeating the other one based on conviction of their legal merits (and/or a purely distributive, financial negotiation). Conversely, others will approach the same situation in an integrative 8 manner, once purged from its emotional elements and freed from its purely legal frame; with or without the help of a neutral, such as a mediator, they will be able to turn the dispute into a setting for integrative bargaining, or even positive resolution. The actual context of the negotiation therefore becomes secondary to the way negotiators will choose to act at the table. We consider the negotiation to be integrative when a negotiator sees the other party as a partner with whom he must build a common solution. We consider the negotiation to be distributive when the negotiator sees the other party as an adversary that he must defeat. Note that when one assumes this and acts accordingly, this may become a self-fulfilling prophecy. In other words, the negotiator’s mindset is integral to whether he sees the other party’s satisfaction as positively or negatively correlated with his own satisfaction. The Impact of the Negotiator’s Mindset on the Three Dimensions In terms of behavior, we propose to analyze the difference between the two mindsets through the lens of the three dimensions. We illustrate this below as three behavioral continua represented by “rev counters” (tachometers, to those classically-trained in technology), each representing one of the three dimensions in negotiation. This “continuum” approach facilitates illustrating how the negotiator’s initial mindset will fluctuate according to how the negotiation progresses and to the tactical choices made by the parties. Whether a negotiator will act in one way or another does not simply depend on the “dosage” of the choices, but also on their sequencing. Each negotiator finds their 9 balance by navigating from one extreme to the other (or, in the rev counters, from left to right). The first rev counter represents the substance dimension. It allows identifying two behavioral continua: the integrative negotiator’s behavior goes from pure cooperation to pure competition, whereas the distributive one goes from competition to manipulation. Along the negotiation, behaviors will vary between the two “extremes” that represent pure cooperation and manipulation. Integrative negotiation is thus not defined as cooperation, but as a mix of cooperation and competition. But that takes us only halfway around the rev counter. Manipulation should be defined as feigned cooperation; you make the other party believe that you are cooperating when in fact you are only serving your own interests. And this takes up the remainder of the meter’s range. The idea here is to integrate, by enriching it, the concept of mixed motive, offered for the first time by Thomas Schelling (1960) and so often presented as an essential tension for any negotiation situation. 10 The second rev counter, representing the relationship dimension, shows the integrative negotiator’s behavior ranging between empathy and assertiveness, that is, alternating listening to the other and expressing oneself. The distributive negotiator will, on the other hand, work between assertiveness and coercion: he does not listen sincerely to the other parties, but tries to persuade them, even threatens if necessary. While the integrative negotiator’s focus will be centered on all the actors, and therefore their interpersonal relations, the distributive’s focus will only be on himself and his interests. Whereas the former sees the relationship as a balanced playing field on which to grow the agreement, the latter will consider the relationship only as a source of personal gain. For such a negotiator, listening is used mostly to find a way through which he can impose his viewpoint, or destabilize the other party (directive, distracted, or impassive listening, etc.). Another way to look at this is to consider the question of information exchange: whereas the integrative negotiator will share information for the common good, the distributive one will try to skew the exchange in his favor. 11 The third rev counter, representing the process dimension, shows how the integrative negotiator’s behavior toward the negotiation process is split between paying attention to external interests and needs (that is, in relation to the other parties) and internal (paying attention to the people, organizations and interests he is specifically there to defend at the table). This conception of process is oriented toward having principals get heavily involved, using negotiators as spokespersons; the preferred process is therefore designed for efficiency for both parties. Distributive negotiators, by contrast, are likely to place themselves on the upper half of the scale, i.e. between an “internal” focus and unfair tactics. This means they will resort to processual ways to put pressure on the other party, in order to unilaterally gain more, and faster, on the substance. Where the integrative negotiator will work to create a link between his own mandate and that of the other party, the distributive negotiator will use the process to try to enforce his influence on the other party. A diagnostic tool 12 Without going into too sophisticated a process approach to negotiation, it is therefore possible to alert negotiators about how one’s mindset may impact their behaviors on each of the three dimensions of negotiation (Relationship – Process – Substance). First, this implies that the negotiator’s mindset does not impact just the substance dimension; the way a negotiator looks at the process and the relationship dimensions is also colored by her assumptions about negotiation. One’s distributive tendency may appear visible in any of the dimensions. Although the three counters may move in parallel with one another, this may not necessarily be the case; hence, how the other negotiator behaves in terms of substance may hide a different mindset on the other dimensions. A negotiator may act in an integrative manner on the relationship dimension, thus giving the impression he will be integrative on the substance… to better hide a distributive stance. Another negotiator may build a very distributive process, serving his interests only, and then act collaboratively on the substance; this is sometimes the case with purchasing centers, when they opt to (or are forced to) try and protect their weakest suppliers from their own aggressive pricing policies.For more experienced professionals, such a tool serves not only to understand the behavior of our counterparts but also as a useful self-diagnosis tool – to assess our own behavior at the negotiation table. By looking at evidence of distributive behavior on each of the dimensions, one may be able to anticipate non-collaborative actions by the other party. Also, one may be able to self-diagnose oneself by looking at hints of behaviors on each of the dimensions. Am I considering manipulating the other party through communication? Or am I skewing the process to better serve my own interests? Also, the 13 most integrative-oriented negotiator may sometimes let slip a manipulative action that could have some pervert impact on the negotiation process. The rev counter metaphor presents another asset: it indicates that when negotiation becomes tense or complex, a negotiator who feels under pressure, or simply emotional, may “rev up”, and therefore abandon integrative behaviors for more distributive ones. This may be done consciously by particularly reflective negotiators, or unconsciously by the greater number. Such a shift can be observed, through different forms, in one, two or three of the dimensions of the negotiation at a time. Conclusion Three dimensions, two mindsets, six possibilities. Our approach first enables looking at negotiation as a process, with stages that need to be aligned (not necessarily linearly) by surfing on the three dimensions of negotiation. Furthermore, defining negotiation as a matter of mindset basically means that any negotiation may be distributive or integrative, depending on one’s approach to the situation. What this chapter does not say is how to change the other negotiator’s mindset; for this, we invite readers to refer to the notions of “negotiation jujitsu” and “changing the game” offered by Fisher and Ury (1981). Finally, the three dimensions may serve as a diagnostic tool, both for ourselves and for the other party: by looking for traces of distributive behavior on each of the dimensions, a perceptive negotiator may be able to anticipate distributive moves, whether they come from himself or the other party. 14 References Axelrod, R. 1984. The Evolution of Cooperation. New York NY: Basic Books. Caillé, A., and J.E. Grésy. 2014. La Révolution du Don. Paris: Seuil. Fisher, R. and W. Ury. 1981. Getting to Yes. New York NY: Penguin Books Halifa, Y. and G. Cantournet. 2011. Le Syndrome du Lapin dans la Lumière des Phares. Saint-Julien-en-Genevois : Jouvence. Lempereur, A., A. Colson and M. Pekar. 2010. The First Move: A Negotiator’s Companion. London: Wiley. Lewicki, R., D. Saunders and B. Barry. 2014. Negotiation. Columbus OH: McGraw-Hill Education. Mnookin, R., S. Peppett and A. Tulumello. 2000. Beyond Winning: Negotiating to Create Value in Deals and Disputes. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. Pinkley R. L. and G. B. Northcraft. 1994. Conflict frames of reference: implications for dispute processes and outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 193–205. Schelling, T. 1960. The Strategy of Conflict. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. 15