Patent Alchemy: The Market for Technology in US History and Dhanoos Sutthiphisal

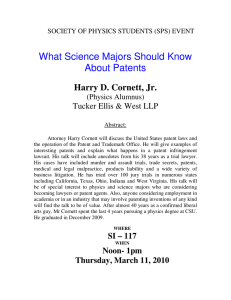

advertisement