Factors that influence patient and public

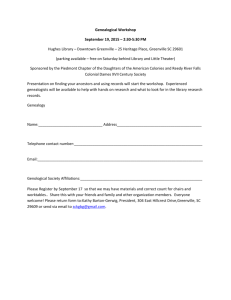

advertisement

Department of Applied Health Research Factors that influence patient and public views about proposals for major service change: evidence from the English NHS Helen Barratt, Naomi Fulop, Rosalind Raine Department of Applied Health Research Background • • 1Imison Health care systems face the challenge of meeting rising demand with diminishing resources For policy commentators, decisions about organising care involve ‘trade-offs’ between interlinked factors1 C. Reconfiguring hospital services. London: King's Fund, 2011 . Background • In England, proposed service changes such as A&E closures often face public opposition • Government policy emphasises the role of clinical evidence to convince the public of the need for change Aim • To examine whether patients + the public are willing to accept the trade-offs involved in such decisions Department of Applied Health Research Study design • In-depth interviews in two urban areas: • Area 1: ‘Greenville’ – service changes proposed – Parents of young children (n=5) – Older people (n=6) – Activists and patient reps (n=9) • Area 2: ‘Hilltown’ – no changes proposed – NHS patients with chronic condition (n=8) • Analysis combined inductive and deductive approaches with sociocultural perspectives of risk as an analytic focus Interview flash cards • Participants invited to select their priorities for A&E from a range of flash cards – Aspects they might be prepared to have ‘less’ of (e.g. quick access)… – …if it meant having ‘more’ of another (e.g. consultant-delivered care) • • • • • • • • A local hospital to serve the local community Good bus or tube links Easy to park Patients can choose which A&E to go to Sick patients taken to A&E as fast as possible Consultants on duty in A&E 24 hours a day Patients’ care meets nationally agreed standards of quality A&E convenient to get to for patients and their families Findings Four groups in terms of response Group 1 (n=2/28): • Willing to consider longer journey in an emergency • Only Greenville interviewees in favour of change • Both had close contact with medical profession Group 2 (n=5/28): • Rejected trade-off approach as overly simplistic • Response would depend on variables including: – Severity of the situation – Additional distance Findings Group 3 (n=2/28): • Challenged concept of making trade-offs in context of health care I don't think trading off... We should never ever have to trade-off with national health services. It's okay to discuss it, but it's not something that should be considered. Why don't they just upgrade services all round? (Greenville Parent 4) Findings Group 4 (n=11/28): •Perspective of majority of participants •Unwilling to accept trading-off any aspects of care with access In extreme circumstances it could be the matter of between life and death, couldn’t it? In an extreme situation, you know, taking your child to hospital, minutes could be critical. So having a facility further away is... No, it’s not ideal at all.... [Getting there] is critical... I think having a facility nearby is essential, absolutely essential. (Greenville Parent 2) Risk • Interviewees would be ‘frightened’ or ‘worrying’ • Unclear how to help a sick relative • ‘Burden’ of caring passed on on arrival at hospital • Implicit assumption: timely access = better outcomes – ‘Every minute counts’ - time ‘is of the essence’ • Get to the ‘experts’ and ‘get seen quickly’ Health care is quite simple, I don’t feel very well, my wife doesn’t feel very well, I want to get myself, my wife or my child to somewhere quickly where someone competent can do a triage and say you’re dying, its indigestion or we’re putting you in for surgery. (Greenville Activist 7) Risk • Douglas: risk = probability + probable magnitude of outcome • Participants clear that probability small –‘The really big stuff happens thankfully less often and might not even happen at all’ (Greenville Parent 3) • Public select a risk because they value what is under threat –Risk = possibility of negative outcomes • Travelling further for care constituted ‘unacceptable danger’ It's my life! I mean it could be my life... I may not die, but maybe they could help prevent something worse happening. Prevent catastrophe, maybe. (Greenville Parent 4) Quality of care • Quality of care = interpersonal quality of care – Timeliness – ‘not having to sit around for hours’ – Attentiveness of staff - ‘having plenty of staff around’ • If an ED closes: – ‘Double’ the number of patients will attend the alternative – Staff would be ‘swamped’ • Technical aspects of care not ‘gains’ worth having – Perception of little difference between hospitals (and doctors) – Lack of clarity about role of consultants Conclusions • Clinical leadership + detailed explanation of case for change were insufficient to overcome opposition in Greenville • Most participants not prepared to travel further because of a belief that timely access = better outcomes • Participants perceived service consolidation would decrease the safety and quality of care • Participants held similar views in both areas, suggesting that these perceptions are widely held Conclusions • Previous research has largely concentrated on policy issues • No studies have formally examined the views of patients and members of the public at large • Little information to date on whether views vary within and across populations • Findings based on a single reconfiguration in an urban area • Qualitative approach permitted in-depth exploration of public response when discussions about change were ongoing Implications for policy and practice • We cannot assume that evidence will persuade communities to accept service change • Commissioners should: • Make explicit plans to accommodate changes in patient flows • Clarify the roles of key staff groups for the public • Acknowledge local experience e.g. about public transport Acknowledgements • • • • • • Prof Rosalind Raine Prof Naomi Fulop Dr David Harrison - ICNARC Interview participants Individuals who helped pilot topic guide + flash cards Individuals who assisted with recruitment Work funded by a Wellcome Trust Research Training Fellowship (WT091024MA)