Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology 4(10): 1403-1413,... ISSN: 2040-7467

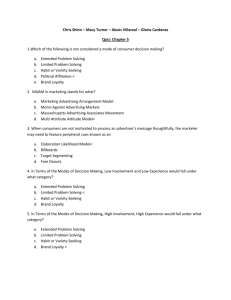

advertisement

Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology 4(10): 1403-1413, 2012 ISSN: 2040-7467 © Maxwell Scientific Organization, 2012 Submitted: January 30, 2012 Accepted: March 10, 2012 Published: May 15, 2012 An Analysis of Some Moderating Variables on the Value, Brand Trust and Brand Loyalty Chain 1 Kambiz Heidarzadeh Hanzaee and 2Leila Andervazh Department of Business Management, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran 2 Department of Business Management, Persian Gulf International Educational Center, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Iran 1 Abstract: The objective in this study was to investigate the moderating effect of some variables on the value, brand trust, and brand loyalty chain. These moderating variables are customer characteristics (Age, Gender, Involvement, Price consciousness, Brand consciousness). More specifically, we investigate both the link between hedonic and utilitarian values of a product and brand trust and the link between brand trust and attitudinal and purchase loyalty and the impact of selected customer characteristics on these relationships in the context of four product groups (mobile phones, sunglasses, running shoes, and notebooks) that can be characterized as consumer durables with high brand relevance. In a basic research model after reviewing the literature on brand trust, hedonic and utilitarian value as selected contributors to brand trust and brand loyalty as an important outcome of trust, we measured the effects of product value-brand loyalty on brand trust. Then in the second phase we analyzed the moderator effects. The proposed relationships have been tested using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) via lisrel. We first report the main effect model and then present the impact of moderators. Key words: Brand consciousness, hedonic value, involvement, price consciousness, utilitarian value INTRODUCTION Trust is one of the most effective methods of reducing uncertainty. Studies illustrate the importance of trust in developing positive and favorable attitudes, resulting in commitment to a certain brand in successful consumer-brand relationships (Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Fournier, 1998; Gurviez, 1996). Consumer’s trust in a brand contributes to a reduction in consumer uncertainty in consumer (Gommans et al., 2001; Fullerton, 2003), and is believed to increase customer loyalty (Narayandas, 1998; Ergin and Akbay, 2010). Most discussions of trust agree that confident expectations and risks are critical components. For example, Deutsch (1958) defines trust as the confidence that one will find what is desired from another, rather than what is feared. Similarly, Morgan and Hunt (1994) and Lewicki et al. (1998) also consider confidence expectations as key element of trust. Trust matters only when a person is in a situation that involves uncertainty, vulnerability or risk about an outcome (Mayer et al., 1995). A strong brand is a trust mark (highly regarded by consumers) because it signals high product quality or reliability, evokes consumers’ feelings of security, and enhances their confidence that a product offering will deliver what they expect (Aaker, 1996). Brand loyalty has been proclaimed to be the ultimate goal of marketing (Reichheld et al., 2000). Brand loyalty is consequence of brand trust. Many companies try to enhance brand loyalty among their customers. The objective in this research is to investigate the moderating effect of some variables on the value, brand trust, and brand loyalty chain. These moderating variables are customer characteristics (Age, Gender, Involvement, Price consciousness, Brand consciousness). LITERATURE REVIEW Brand trust: A brand is commonly referred to as the name, term, design, symbol, or any other feature that identifies one seller's goods/services as distinct from those of other sellers (Aaker, 1996). The Importance of trust in developing positive and favorable attitude and, the relation of commitment-loyalty has been examined by many researchers, resulting determining that in commitment to a certain brand forms a in successful consumer-brand relationship (Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Fournier, 1998; Gurviez, 1996). Consumer’s trust in a Corresponding Author: Kambiz Heidarzadeh Hanzaee, Department of Business Management, Ashrafee e-Esfahani Highway, Hesarak Road, Tehran, Iran, Zip code: 1477893855 1403 Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(10): 1403-1413, 2012 brand contributes to a reduction of uncertainty in consumer purchases (Garbarino and Mark, 1999; Gommans et al., 2001) and is believed to increase customer, (Fullerton, 2003; Narayandas, 1998); trust as the single most powerful relationship-based marketing tool (Berry, 1995). Drawing on the above mentioned literature we define brand trust as: the feeling of security held by the consumer in his/her interaction with the brand, witch that is based on the perceptions that the brand is reliable and responsible for the interests and welfare of the consumer. In marketing literature, the term "brand trust" is variously defined as the willingness of consumers (implying a propensity) to rely on the ability of the brand to perform its stated function (Chaudhuri and Holbrook, 2001); as the confident expectations of the brand's reliability and intentions in situations entailing risk to the consumer (Delgado-Ballester, 2004; Delgado-Ballester and Munuera-Alema'n, 2001): or simply described in terms of reliability and dependability (Dawar and Madan, 2000). These definitions of brand trust suggest that an individual’s propensity (a conscious inclination) to trust on a brand’s qualities or attributes is critical in consumerbrand relationships. First of all consumers rely on trusted brands to economize time and other search costs (Zeithaml, 1988). Moreover it’s trust that allows the consumer to develop a personal relationship with the brand (Hess and Story, 2005). Brand trust leads to brand loyalty because trust creates exchange relationships that are highly value (Morgan and Hunt, 1994). Most recently, some marketing scholars have also found that trust and loyalty are very important constructs affecting customer performance behavior (Bettencourt, 1997; Garbarino and Mark, 1999). In particular, both loyalty and trust also play very important roles in affecting customer performance behaviors in relationship marketing. The importance of trust in an exchange relationship has been demonstrated in marketing (Morgan and Hunt, 1994). Literature (Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Dwyer and Schurr, 1987). Its effects on commitment-an "enduring desire to maintain a valued relationship” have also been well supported in the literature (Morman et al., 1992). Therefore, it is expected that a brand that demonstrates reliability and integrity ensures consumers’ willingness to keep the relationship and encourage future purchases. Following this logic, this study proposes that brand trust positively affects on brand loyalty. Brand loyalty: Loyalty has received considerable attention in marketing literature for over 80 years (Copeland, 1923). Loyalty was been defined and measured in relation to several marketing aspects such as brand loyalty, product loyalty, service loyalty, and chain or store loyalty (Olsen, 2007). Loyalty has a powerful impact on firm performance, (Edvardsson et al., 2000; Lam et al., 2004; Reichheld et al., 2000; Mitchell and Goldrick, 1996). Firms gain a competitive advantage by having a high loyal consumers, who are willing to pay higher prices and are less price sensitive (Morman et al., 1992). Brand loyalty provides the firm with trade leverage and valuable time to respond to competitive moves. Understanding the concept of loyalty helps companies better manage customer relationship management in order to create long-term investment and profitability (Mitchell and Goldrick, 1996). Brand loyalty implies that consumers have a good attitude towards a particular brand over other competing brands. Brand loyal consumers may be willing to pay more for a brand because they perceive some unique value in the brand that no alternative can provide (Oliver, 1993). THEORETICAL MODEL In this section, the researchers focus investigating the influence of product value on brand trust and the impact of brand trust on brand loyalty for four consumer durables with high brand relevance. Specifically, the researchers focused on hedonic value and utilitarian value as drivers trust and purchase loyalty and attitudinal loyalty as outcomes of brand trust (Day, 1969). Hedonic and utilitarian value: Adapted literature cited earlier suggests that there exist two kinds of consumer evaluations exist ,in which the consumption object is cognitively placed on both a utilitarian dimension of instrumentality (e.g., how useful or beneficial the object is), and on a hedonic dimension measuring the experiential effect associated with the object (e.g., how pleasant and agreeable those associated feeling are). There is a strong correlation between hedonic value, risk and brand affect, antecedent to brand commitment. Thus brands that make consumers happy will be associated with greater commitment. Emotions and feelings of enjoyment or pleasure are key components in purchase decisions (Chaudhuri and Holbrook, 2001). There are two broadly different types of products with tangible, objective features that offer functional benefits, and primarily hedonic products with subjective, in tangible features that produce enjoyment or pleasure (Chaudhuri and Holbrook, 2001). Both of these types of benefits contribute, in differing degrees, to the overall goodness of consumer goods or behaviors (Batra and Aholta, 1990; Oliver, 1993). Concerning the relationship between product value and brand trust it can be assumed that cognitive trust toward a specific brand is greater, when the utilitarian 1404 Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(10): 1403-1413, 2012 value of the product in terms of e.g. quality or convenience is high (Chaudhuri and Holbrook, 2001). On the other hand, products with a high pleasure potential provide no tangible, symbolic benefits and are likely to hold a greater potential for evoking positive emotions and effect-based brand trust in a consumer. The utilitarian value perspective puts emphasis on consumer’s perception on functional performance in the purchasing or decision-making process. When consumers’ needs are fulfilled and/or when there is a balance between quality and price (cost), they experience utilitarian value. Feeling the ambiance that creates enjoyment (hedonic value) is a critical aspect of consumers’ consumption experience (Babin and William, 1995). In summation, the previous literature implies the following hypothesis: H1: Utilitarian value and hedonic value will be positively related to brand trust. Attitudinal and purchase loyalty: Brand loyalty is defined as the commitment to using a deeply product/service consistently in the future, thereby causing repetitive same-brand-set purchasing, despite situational influence and marketing efforts having the potential to cause switching behavior (Oliver, 1993). This definition emphasizes the two different aspects of brand loyalty that have been described in previous work on the concept behavioral and attitudinal (Aaker, 1991; Assael, 1998; Jacoby and Chestnut, 1978). Behavioral or Purchase Loyalty consists of repeated purchases of the brand, whereas attitudinal brand loyalty includes a degree of dispositional commitment in terms of some unique value associated with the brand. Some researchers examined that brands high in consumer trust and effect (emotional) are linked through both attitudinal and purchase loyalty (Chaudhuri and Holbrook, 2001). Brand trust leads to brand loyalty because trust creates exchange relationships that are highly valued (Morgan and Hunt, 1994). Thus loyalty underlies of consumer trust. In other words, trust and loyalty should be associated, because trust is important in relational exchanges and loyalty is also reserved for such valued relationships. Brand trust will contribute to both purchase and attitudinal loyalty (Chaudhuri and Holbrook, 2001). Trusted brands should be purchased more often and should evoke higher degree of attitudinal loyalty. We considered two types of loyalty: attitudinal loyalty and behavioral or purchase loyalty. Attitudinal loyalty, in contrast to behavioral loyalty, purchase or behavioral loyalty is distinguished from repeat buying attitudinal loyalty defined as the level of customer's psychological attachments and attitudinal advocacy towards the service provider or supplier (Mellens et al., 1996; Jacoby and Chestnut, 1978). Attitude denotes the degree to which a consumer's disposition towards a product is favorable. Attitudinal loyalty focuses on the cognitive basis of loyalty and isolates purchases driven by a strong attitude from purchases due to situational constraints. Attitudinally loyal customers are committed to a brand or company and they make repeat purchases based on a strong internal disposition (Rauyruen and Miller, 2007). Attitudinal loyalty is also viewed as the extent of the customer's psychological attachments and attitudinal advocacy towards the organization (Jacoby and Chestnut, 1978). Accordingly, attitudinal loyalty encompasses positive word of mouth intentions, willingness to recommend to others and encouraging others to use the products and services of a company (Zeithaml, 1988). Therefore we propose this hypothesis: H2: Brand trust will be positively related to Attitudinal and Purchase loyalty: Based on the above discussion, the two hypotheses suggested above are summarized in Fig. 1. MODERATING VARIABLES Gender and age: Demographic characteristics that have been found to influence an individual’s purchase intention and behavior in a number of different contexts are gender and age. Compared to men, women are more involved in purchasing activities (Slama and Tashlian, 1985). Johnson-George and Swap (1982) found that men and women look for different attributes in another person when assessing her or his trustworthiness. Drawing on findings in the personality and social psychology literature, Chen and Dhillon (2003) propose that both age and gender significantly influence the perception of competence, integrity and benevolence of an Internet vendor, and thus consumer trust in ecommerce. Hence, we suggest age and gender to be moderators of the relationships between value, brand trust, and brand loyalty. Involvement: The involvement construct has played an increasingly important role in analyzing and explaining consumer behavior. The level of consumer involvement is a crucial factor influencing buying decisions and is discussed by both attitudinal and behavioral theorists when addressing the issue of brand loyalty (Bennett et al., 2005). Although there is no universally accepted precise definition of involvement, most researchers agree that the level of involvement is related to the level of perceived personal relevance of a certain product for the consumer (Homburg and Giering, 2001; Knox et al., 1993). Laurent and Kapferer (1985) conceptualize consumer involvement as a multidimensional construct consisting of five determinants: 1405 Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(10): 1403-1413, 2012 Fig. 1: Structural modle C C C C C Personal meaning and self-reference Ability to provide pleasure Ability to express the person’s self Perceived importance of negative consequences, which means the perceived importance of purchase risk Perceived probability of purchase risk To sum up, the level of involvement indicates how important a product and the consequences of its purchase are for the individual. Hence, involvement is suggested to moderate the relationships between product value, brand trust, and brand loyalty. For example, individuals with high product or enduring involvement might perceive a greater pleasure potential of the product, and therefore the influence of hedonic value on brand trust might be more dominant than for lowly involved persons. Price consciousness: Whereas Zeithaml (1988) used the term in a wider sense referring to different price-related cognitions, Lichtenstein et al. (1993) were the first authors to conceptualize the construct of price consciousness in a narrower sense as “the degree to which the consumer focuses exclusively on paying low prices” (Lichtenstein et al., 1993). They point out that their definition is consistent with the conceptualization of several other authors (Tellis and Gaeth, 1990; Lichtenstein et al., 1993; Monroe and Petroshius, 1981; cited by Lichtenstein et al., 1993). Sinha and Batra (1999) refer to the unwillingness of consumers to pay a higher price for a product and are in line with Monroe and Petroshius (1981), who conceptualize price consciousness as individual differing reluctance to pay for additional or distinguishing features of a product, if the price difference is too large. Miyazaki et al. (2000) define price consciousness as individual difference variable reflecting the “enduring motivation to consider unit price information” (p. 98). Price consciousness is among a variety of other psychological constructs explaining price perception of consumers in the marketplace. As “price is unquestionable one of the most important marketplace cues” (Lichtenstein et al., 1993), it plays two different roles in influencing purchase probabilities: a negative role as it means giving a certain amount of money in exchange for goods and services, but also a positive role as higher prices are cues for higher quality (Sternquist et al., 2004; Lichtenstein et al., 1993; Lichtenstein et al., 1988; Erickson and Johansson, 1985). Price consciousness is one of the five constructs consistent with the negative role of price-the others are value consciousness, price mavensim, sale proneness and coupon proneness (Lichtenstein et al., 1993). Price consciousness has been increasing in awareness of the consumers in the last few years. One of the reasons is that consumers focus on cheaper products in order to sustain their standard of living (Rothenberger, 2005; Simon, 2004). Price consciousness is a crucial factor influencing purchase behavior. Highly price-conscious consumers express lower perceptions of offer value and higher price information search intentions (Alford and Biswas, 2002). According to Alford and Bsiwas (2002) highly price conscious consumers derive emotional value from looking for even lower prices. They get rewarded if lower prices have been found and are proud of their “success”. The consumers’ level of price consciousness therefore influences the propensity to search for prices (Urbany et al., 1996), the sensitivity of price-oriented sales promotions (Lichtenstein et al., 1988; Blattberg and Neslin, 1990; Lichtenstein et al., 1990), the propensitiy to 1406 Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(10): 1403-1413, 2012 redeem coupons in different product categories (Swaminathan and Bawa, 2005) and the knowledge of unit prices as they are vigilant in paying lower prices and therefore motivated to process pricing information (Manning et al., 2003; Miyazaki et al., 2000). In our study the interest has been focused on the variation across consumers, not on differing between product categories. Sinha and Batra (1999) demonstrated that consumers are less priceconscious in buying products in categories with high perceived risk. As loyalty is one strategy of risk reduction, price consciousness may moderate the valuebrand trust-brand loyalty chain. It is assumed that price consciousness weakens the influence of hedonic value to trust and strengthens the path from trust to attitudinal and purchase loyalty. As mentioned above, highly price conscious consumers gain emotional reward from looking for even lower prices and are motivated to search for additional information and therefore elaborate their purchase decision instead of relying on a known brand. Hence, trust becomes an important missing link between hedonic value and loyalty for highly price conscious consumers as it reduces their reluctance to be loyal. The path between hedonic value and trust is assumed to be stronger for less price conscious consumers. For highly price conscious consumers instead, a low price has a higher emotional value than the hedonic value of a product. Hence, trust may have other, more important antecedents than hedonic value of the brand for highly price conscious consumers. Brand consciousness: Nelson and McLeod (2005) do not differ conceptually between brand consciousness and brand sensivity. According to these authors, these constructs have been studied to manage brands (Laurent and Kapferer, 1985), to understand consumer socialization processes and to investigate the different feelings ofconsumers against imitation of brands. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY The objective of this study is to provide additional insight into the product value-brand trust-brand loyalty chain by examining the effects of moderating variables. A 12 item questionnaire developed and Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001) was used to measure Brand trust, utilitarian value, hedonic value, purchase loyalty and attitudinal loyalty. A standardized self-administered questionnaire was developed to test the proposed relationships for four products (mobile phones, sunglasses, running shoes, and Notebooks). Subjects for the study were randomly selected people that have been approached during shopping hours in shopping streets in Tehran. Data collection took place between 9 a.m. and 7 p.m. on five working days. Table 1: Characteristics of the sample Frequency Percent Gender Male Female Total Age 18-24 Year 25-34 Year 35-44 Year 45 and older Total Valid percent Cumulative percent 155 195 350 44.3 55.7 100.0 44.3 55.7 100.0 44.3 100.0 69 112 99 70 350 19.7 32.0 28.3 20.0 100.0 19.7 32.0 28.3 20.0 100.0 19.7 51.7 80.0 100.0 To measure the moderating variables including Involvement with 16-items by Laurent and Kapferer (1985), Brand consciousness and price consciousness with 3-items by Walsh et al. (2001)and Lichtenstein et al. (1988) . A five point scale was constructed ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). For internal reliability, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated for all items of each construct. Results indicated that all the scales were considered to be reliable (Cronbach’s alphas). To measure the effects of product value on brand trust and brand loyalty, using the scale developed by Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001). Moderating variables were contained: involvement with 16-items were developed by Laurent and Kapferer (1985). To measure the moderating variables on the value, brand trust and brand loyalty a 33-items questionnaire, was used that was developed by (Matzler et al., 2006) that shown in Table 2. Consequently, the thirty three item. Scale was taken into account for brand trust with 4-items,utilitarian value with 2-items,hedonic value with 2-items purchase loyalty with 2-items, attitudinal loyalty with 2-items, were measured using the scale developed by Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001). Involvement was measured with 16 items by Laurent and Kapferer (1985). Brand consciousness with 6 items, developed by Walsh and price consciousness with1item developed by Lichtenstein. All statements were measured on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). For internal reliability. Coronbach's alpha coefficients were calculated for all items of each construct. Results indicated that all the scales were was considered to be reliable. For detetermining reliability and validity of the questionnaire in this research used Coronbach's alpha was used. Coronbach's alpha for the constructs are: hedonic value:. 752, utilitarian value:. 738, brand trust:. 773, purchase loyalty:. 787, and attitudinal loyalty:. 726 so reliability of this questionnaire is acceptable. For determining validity, discriminant validity was assessed for all constructs and indicators. Discriminant validity was assessed by 1407 Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(10): 1403-1413, 2012 Table 2: Reliability and overall measurement model Construct Item Utilitarian value I rely on this product This product is a Hedonic value I love this product I feel good when I use Brand trust I trust this brand I rely on this brand This is an honest brand This brand is safe Purchase I will buy this brand the I intend to keep Attitudinal I am committed to this I would be willing to Table 3: Fit indices Recommend Model-fit index value Recommender #3 Fox et al. (2006) X2/df RMSEA #0.8 Fox et al. (2006) RMR #0.5 Fox et al. (2006) NFI >0.90 forza and filippini (1998) GFI >0.80 Fox et al. (2006) CFI >0.90 Fox et al. (2006) AGFI >0.80 Forza and Filippini (1998) PGFI >0.50 Kayank (2003) PNFI >0.50 Kayank (2003) Factor loadings 0.75 0.77 0.86 0.70 0.58 0.48 0.46 0.49 0.80 0.81 0.79 0.73 Structural model 2.9975 0.0760 0.0310 0.9600 0.9400 0.9800 0.8900 0.5300 0.6400 examining the factor loading for statistical significance. All the results of these measures were significant and are shown in Table 2. To ensure of the validity and reliability of the questionnaire a pilot test were used before the formal survey. This pilot test contained 30 buyers (mobile phone, notebooks, running shoes, sunglasses). The results of this test indicated that coronbach's " did include the necessary values and validity was verified. In this research overall 350 usable questionnaire were collected (140 mobile phone buyers, 45 notebook buyers, 98 running shoes buyers, and, 66 sunglass buyers. Table 1 displays the characteristics of the sample. RESULTS The proposed hypotheses were tested using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) via LISREL. As said, the relationship between hedonic and utilitarian value brand trust and brand loyalty was measured, then we measured the effects of moderating variables (gender, age, involvement, brand consciousness and price consciousness) on hedonic and utilitarian value, brandloyalty and brand trust. Various recommenders, test of Fit-indices model is supported. In Table 1 the values shown of recommend values and structural model values are shown. To determine whether the hypotheses were supported, each structural path coefficient was examined with fit R² 0.5 0.5 0.7 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.6 0.6 0.6 0.5 t-value 11.7 11.6 8.72 8.31 8.89 14.7 12.3 CR1 0.88 "2 40.738 AVE 3 0.793 0.890 0.752 0.802 0.857 0.773 0.600 0.905 0.787 0.826 0.879 0.726 0.785 Table 4: Results of hypothesis test Results of hypothesis tests --------------------------------------------------------------Hypothesis path Standardize d estimates t-value Utilitarian value 0.48 4.47 Hypothesis is supported 6 Brand trust Hedonic value 0.40 3.79 Hypothesis is supported 6 B rand trust 0.93 9.92 Hypothesis is supported Brand trust 6 Purchase loyalty 0.89 9.68 Hypothesis is supported Brand trust 6 Attitudinal loyalty indices of the proposed models. The fit indices of models are shown in Table 3. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) indicates “how well would the model, with unknown but optimally chosen parameter values, fit the population covariance matrix if it were available?” The RMSEA’s value of less than 0.08 and RMR = 0.031 both within the acceptable level and indicates a good fit for our model. The Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) is an indicator of the amount of variance and covariance accounted for by the model and a value exceeding 0.90 is considered as reflecting acceptable fit. NFI = 0.96 and PNFI = 0.64 are acceptable range. Last but not least the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) is based on the non-centrality parameter and a value exceeding 0.90 is an indication of good fit. Table 2 contains a summary of the model’s fit statistics, as produced by LISREL 8.8. The combination of their values shows that the hypothesized model unquestionably fits the available data. CONCLUSION This study were included two phases: the first: it examined the effects of main variables, hedonic and utilitarian value on brand trust and brand loyalty and then second we examined the effects of gender, age, involvement, brand consciousness and price consciousness as moderating variables on the product value, brand trust and brand loyalty. Test of main effects: The results of first part are shown in Table 4. 1408 Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(10): 1403-1413, 2012 Table 5: The results of gender Gender ------------------------------------------Hypothesis path (1) Female, N = 195 Male, N = 155 0.32 (T = 1.93) 0.82 (T = 3.27) Utilitarian value 6 Brand trust Hedonic value 6 0.55 (T = 2.48) 0.14 (T = 0.84) Brand trust Brand trust 6 0.92 (T = 2.93) 0.98 (T = 4.05) Purchase loyalty Brand trust 6 0.93 (T = 2.91) 0.59 (T = 3.29) Attitudinal loyalty Difference = -7.60252 Goodness of fit statistics RMSEA Gender ------------------------------------Female Male 0.089 0.080 = 4.398115 NFI 0.94 0.90 = -6.53039 GFI 0.91 0.91 = 9.029261 CFI 0.96 0.94 AGFI 0.84 0.85 Contribution to Chi-Square 134.28 133.43 = 0.85 N.S PGFI 0.51 0.52 Percentage contribution to 50.16 49.84 = 0.32 N.S PNFI 0.63 0.60 Chi-Square RMSEA = Root mean Square Error; NFI = Normal Fit Index; GFI = Goodness fit Index; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; AGFI = Adjusted goodness of Fit Index; PGFI = Parsimonious goodness Fit Index; PNFI = Parsimonious Normal Fit Index Table 6: The results of age Hypothesis path (4) Utilitarian value 6 Brand trust Hedonic value 6 Brand trust Brand trust 6 Purchase loyalty Brand trust 6 Attitudinal loyalty Age ------------------------------------------Young, N = 181 Old, N = 169 0.52 (T = 2.52) 0.48 (T = 3.77) Difference 0.493983 0.39 (T = 1.94) 0.35 (T = 2.95) 0.430034 NFI 0.95 0.96 0.92 (T = 6.07) 0.90 (T = 8.31) 1.084353 GFI 0.91 0.93 0.88 (T = 5.95) 0.94 (T = 8.51) -4.12425 CFI 0.97 0.98 Goodness of fit statistics RMSEA Age -------------------------------------Young Old 0.086 0.071 AGFI 0.85 0.87 Contribution to Chi-Square 113.86 105.84 = 8.02 N.S PGFI 0.52 0.52 Percentage contribution to 51.83 48.17 = 3.66 N.S PNFI 0.63 0.64 Chi-Square RMSEA = Root mean Square Error; NFI = Normal Fit Index; GFI = Goodness fit Index; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; AGFI = Adjusted goodness of Fit Index; PGFI = Parsimonious goodness Fit Index; PNFI = Parsimonious Normal Fit Index The structural model supports the significant and direct pathways proposed in the conceptual model model results show that the Gamma index of the utilitarian value equal to 0.48 and the Gamma index of hedonic value equal to 0.40 on brand trust for the utilitarian equal to 0.99 which has the required value to be meaningful with the confidence level of 0.99. Also brand trust $-indices on purchase loyalty of value 0.93 and brand trust $-indices on attitudinal loyalty with the value of 0.89 have the required value to be meaningful with the confidence level of 99%. According to the results obtained from the proposed model, the hypothesis proposed in the research accepted at the confidence level of 99%. Therefore it can be argued that the brand trust has a direct and significant impact on the utilitarian value and hedonic value affect the behavioral and attitudinal loyalty with the meaningful impact. According to the results of the structural part of the following hypothesis have been answered: The first hypothesis: Utilitarian and hedonic value with the trust have direct relationship. Considering the intensity effect of the utilitarian value of 0.48 calculated from T-value has the required value of 4.47 therefore rejecting the null hypothesis no correlation at 99% level of confidence and a significant positive effect of brand trust on behavioural loyalty is supported. The construct of brand trust, explained about 87% of the variations of behavioral loyalty. Also increased level of brand trust increased attitudinal loyalty. The results of the structural model is shown in Fig. 1. Test of moderating variables: Moderating variables in this study are gender, age, Involvement, brand consciousness and price consciousness. These results are: C C C 1409 The results of gender: The results have shown in Table 5. The results shown that there are no significant difference between male and female groups, but the coefficient related to the impact of utilitarian value on brand trust in male group compared with female is more greater and the impact of hedonic value on brand trust in female is more greater. The results of age: The results have shown in Table 6. The results shown that there are no significant difference between young and old groups, but the coefficient related to the impact of attitudinal loyalty in the old persons compared with young is more greater. The results of involvement: According to the results impact of brand trust on behavioral loyalty in the Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(10): 1403-1413, 2012 Table 7: The results of involvement Involvement ------------------------------------------Hypothesis path (3) Low, N = 165 High, N = 185 0.68 (T = 2.91) 0.40 (T = 3.30) Utilitarian value 6 Brand trust Hedonic value 6 0.13 (T = 0.69) 0.53 (T = 3.89) Brand trust Brand trust 6 0.85 (T = 5.86) 0.99 (T = 8.16) Purchase loyalty Brand trust 6 0.95 (T = 5.85) 0.89 (T = 7.80) Attitudinal loyalty Difference = 3.755017 Goodness of fit statistics RMSEA Involvement -------------------------------------Low High 0.042 0.094 = -4.25309 NFI 0.96 0.95 = -12.8778 GFI 0.95 0.90 = 3.795752 CFI 0.99 0.97 AGFI 0.90 0.83 Contribution to Chi-Square 77.52 136.82 = 59.3 PGFI 0.53 0.51 Percentage contribution to 36.17 63.83 = 27.66 PNFI 0.64 0.63 Chi-Square RMSEA = Root mean Square Error; NFI = Normal Fit Index; GFI = Goodness fit Index; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; AGFI = Adjusted goodness of Fit Index; PGFI = Parsimonious goodness Fit Index; PNFI = Parsimonious Normal Fit Index Table 8: The results of brand consciousness Brand consciousness -----------------------------------------Hypothesis path (6) Low, N = 159 High, N = 191 Utilitarian value 6 0.45 (T = 2.83) 0.52 (T = 3.49) Brand trust Hedonic value 6 0.39 (T = 2.57) 0.37 (T = 2.57) Brand trust Brand trust 6 0.93 (T = 6.71) 0.92 (T = 7.89) Purchase loyalty Brand trust 6 0.91 (T = 5.92) 0.90 (T = 7.90) Attitudinal loyalty Difference = -0.84578 Goodness of fit statistics RMSEA Brand consciousness ------------------------------------Low High 0.68 0.086 = 0.216062 NFI 0.95 0.95 = 0.637105 GFI 0.93 0.92 = 0.517071 CFI 0.98 0.97 AGFI 0.87 0.85 Contribution to Chi-Square 89.91 113.32 = 23.41 PGFI 0.52 0.52 Percentage contribution to 44.24 55.76 = 11.52 PNFI 0.63 0.64 Chi-Square RMSEA = Root mean Square Error; NFI = Normal Fit Index; GFI = Goodness fit Index; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; AGFI = Adjusted goodness of Fit Index; PGFI = Parsimonious goodness Fit Index; PNFI = Parsimonious Normal Fit Index Table 9: The results of price consciousness Price consciousness -------------------------------------------Hypothesis path (2) Low, N = 186 High, N = 164 Utilitarian value 6 0.41 (T = 2.80) 0.56 (T = 3.56) Brand trust Hedonic value 6 0.45 (T = 3.01) 0.32 (T = 2.27) Brand trust Brand trust 6 0.97 (T = 7.12) 0.90 (T = 7.00) Purchase loyalty Brand trust 6 0.92 (T = 6.72) 0.89 (T = 7.19) Attitudinal loyalty Difference = -1.82501 Goodness of fit statistics RMSEA Price consciousness ------------------------------------Low High 0.072 0.070 = 1.416885 NFI 0.96 0.95 = 5.737873 GFI 0.92 0.93 = 1.545524 CFI 0.98 0.98 AGFI 0.86 0.88 Contribution to Chi-Square 88.29 93.61 = 5.32 N.S PGFI 0.52 0.52 Percentage contribution to 48.54 51.46 = 2.92 N.S PNFI 0.64 0.64 Chi-Square RMSEA = Root mean Square Error; NFI = Normal Fit Index; GFI = Goodness fit Index; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; AGFI = Adjusted goodness of Fit Index; PGFI = Parsimonious goodness Fit Index; PNFI = Parsimonious Normal Fit Index C groups owners of high involvement and impact of hedonic value on attitudinal loyalty in the groups owners with low involvement is meaningfully much greater. These results is shown in Table 7. The results of brand consciousness: According to the results impact of brand trust on behavioral loyalty in the groups owners of high brand consciousness and impact of hedonic value on attitudinal loyalty in the groups owners with low brand consciousness is meaningfully greater, but the coefficient related to path of model have no significant impact on two groups. These results is shown on Table 8. The results of price consciousness: The results have shown in Table 9. The results shown that there are no significant difference between two groups, but the 1410 Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(10): 1403-1413, 2012 coefficient related to the impact of behavioral loyalty in the group owners with high price consciousness with comparing group owners low price consciousness is meaningfully greater. These results have shown in Table 9. Limitations and future research: Overall, the results of this study provide encouraging empirical support both for the theory based product value-brand trust-brand loyalty chain as well as for the hypothesized moderating effects on the relationships between brand trust and product value as one of its antecedents, and brand loyalty as one of its outcomes. Hence, this research makes a significant contribution towards a better understanding of the relationships between product value, brand trust, and brand loyalty. Future research should build upon the findings of this study and attempt to provide further insight into the nature of these relationships. REFERENCES Aaker, D.A., 1996. Building Strong Brands. The Free Press, NY. Assael, H., 1998. Consumer Behavior and Marketing Action. 6th Edn., Cincinnati, Ohio, South-Western. Alford, B., L. and Biswas, Abhijit 2002, The effects of discount levelm price consciousness and sale proneness on consumers’ price perception and behavioural intention, J. Bus. Res., 55, 775-783 Batra, R. and O.T. Ahtola, 1990. Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian sources of consumer attitudes, makert. Lett. 2(2): 159-170. Babin, B.J. and R.D. William, 1995. Consumer selfregulation in a retail environment. J. Retailing, 71(1): 47-70. Berry, L., 1995. Relationship marketing of servicesgrowing interest, emerging perspectives. J. Acad. Market. Sci., 23: 236-245. Bettencourt, L., 1997. Customer voluntary performance: Customers as partners in service delivery. J. Retailing, 7: 383-406. Bennett, R., H²rtel, C.E., and J.R. McColl-Kennedy, 2005, Experience as a moderator of involvement and satisfaction on brand loyalty in a business-to-business setting, 02-314R, Indust. Market. Manage., 34, 97107. Blattberg, R.C. and S. A. Neslin., 1990. Sales Promotion: Concepts, Methods, and Strategies, 1st Edn., Englewood Cliffs, Prentice Hall, NJ. Chaudhuri, A. and M.B. Holbrook, 2001. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Market., 65: 81-93. Chen, S.C. and G.S. Dhillon, 2003. Interpreting dimensions of consumer trust in e-commerce. Inform. Technol. Manage., 4: 203-318. Copeland, M.T., 1923. Relation of consumer’s buying habits to marketing method. Harvard Bus. Rev., 1: 282-289. Dawar, N. and M.P. Madan, 2000. Impact of productharm crises on brand Equity: The moderating role of consumer expectations. J. Market. Res., 37: 215-226. Day, G.S., 1969. A two-dimensional concept of brand loyalty. J. Advertising Res., 9: 29-35. Delgado-Ballester, E., 2004. Applicability of a brand trust scale across product categories-A multi group invariance analysis. Eur. J. Market., 38(5-6): 573-592. Delgado-Ballester, E. and J.L. Munuera-Alema'n, 2001. Brand trust in the context of consumer loyalty. Eur. J. Market., 35(11-12): 1238-1258. Deutsch, M., 1958. Trust and suspicion. Conflict Resolution, 2(4): 265-279. Dwyer, F.R., P.H. Schurr and S. Oh, 1987. Developing buyer-seller relationships. J. Market., 51: 11-27. Edvardsson, B., M.D. Johnson, A. Gustafsson and T. Strandvik, 2000. The effects of satisfaction and loyalty on profits and growth: Products versus services. Total Qual. Manage., 11(7): 917-927. Ergin, E.A. and H.O. Akbay, 2010. Consumers’ Purchase Intentions for Foreign Products: An Empirical Research Study in Istanbul, Turkey, EABR & ETLC Conference Proceedings Dublin, Ireland, pp: 510-517. Fournier, S., 1998. Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. J. Consum. Res., 24: 343-373. Fox, J., 2006. Structural Equation Modeling With the SEM Package in Rstructural equation modeling, 13(3): 465-486. Fullerton, G., 2003. The impact of brand commitment on loyalty to retail service brands. Can. J. Adm. Sci., 22(2): 97-187. Forza, C., and R. Filippini 1998. TQM impact on quality conformance and customer satisfaction: A causal model. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 55(1): 1-20. Garbarino, E. and S.J. Mark, 1999. The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. J. Market., 63(2): 70-87. Gommans, M., K.S. Krishan and K.B. Scheddold, 2001. From brand loyalty to e-loyalty: A conceptual framework. J. Econ. Soc. Res., 3(1): 43-58. Gommans, M., K.S. Krishan and K.B. Scheddold, 2001. From brand loyalty to e-loyalty: A conceptual framework. J. Econ. Soc. Res., 3(1): 43-58. Gurviez, P., 1996. The Trust Concept in the BrandConsumer Relationship. In: Beracs, J., A. Bauer and J. Simon, (Eds.), EMAC Proceedings Annual Conference, European Marketing Academy, Budapest, pp: 559-574. 1411 Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(10): 1403-1413, 2012 Hess, J. and J. Story, 2005. Trust-based commitment: Multidimensional consumer-brand relationships. J. Consum. Market., 22(6): 313-322. Homburg, C. and A. Giering, 2001. Personal characteristics as moderators of the relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty-An empirical analysis. Psychol. Market., 18(1): 43-66. Jacoby, J. and R. Chestnut, 1978. Brand Loyalty Measurement and Management. John Willy & Sons, New York. Johnson-George, C. and W.C. Swap, 1982. Measurement of specific interpersonal trust: Construction and validation of a scale to assess trust in a specific other. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol., 43: 1306-1317. Knox, S., D. Walker and C. Marshall, 1993. Measuring consumer involvement with grocery brands: Model validation and scale-reliability test procedures. J. Marketing Manage., 10(1-3): 147-152. Kayank, O., and Efe, O., M., An algorithm for fast convergence in training neural networks. Presented at the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN'01), Washington DC, July 15-19, 2001. Lam, S.Y., V. Shankar, M.K. Erramilli and B. Murthy, 2004. Customer value, satisfaction, loyalty and switching costs: An illustration from a business-to business service context. J. Acad. Market. Sci., 32(3): 293-311. Laurent, G. and J.N. Kapferer, 1985. Measuring consumer involvement profiles. J. Marketing Res., 22: 41-53. Lewicki, R.J., D.J. McAllister and R.J. Bies, 1998. Trust and distrust: New relationships and realities. Acad. Manage. Rev., 23(3): 438-458. Lichtenstein, D.R., PH. Bloch and W.C. Black, 1988. Correlates of Price Acceptability. J. Consum. Res., 15: 243-252. Lichtenstein, D.R., R.G. Netemeyer and S. Burton, 1990. Distinguishing coupon proneness from value consciousness: An acquisition-transaction utility theory perspective. J. Market., 54: 54-67. Lichtenstein, D.R., M.R. Nancy and G.N. Richard, 1993. Price Perceptions and Consumer Shopping Behavior: A Field Study. J. Market. Res., 30: 234-245. Moorman C.G. Zaltman and R. Deshpande, 1992. Relationships Between Providers and Users of Market Study: The Dynamics of Trust Within and Between Organisatizations. J. Market. Stud., 29: 314-328. Manning, K.C., D.E. Sprott and A.D. Miyazaki, 2003. Unit price usage knowledge: Conceptualization and empirical assessment. J. Bus. Res., 56: 367-377. Matzler, K., S. Granber and S. Bidmon, 2006. The valuebrand trust-brand loyalty chain: An analysis of some moderating variables. Innov. Market., 2(2): 76-88. Mayer, R.C., J.H. Davis and F.D. Schoorman, 1995. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manage. Rev., 20(3): 709-734. Mellens, M., M.G. Dekimpe and J.B.E.M. Steenkamp, 1996. A Review of Brand-Loyalty Measures in Marketing. Tijdschrift Voor Economie en Management, 41: 507-533. Miyazaki, A., D., Sprott, E. David and Manning, C. Kenneth, 2000. Unit prices on retail shelf labels: An assessment of information prominence. J. Retail. 76(1): 93-112. Mitchell, V.W. and P.J.M. Goldrick, 1996. Consumers risk-reduction strategies: A review and synthesis. Int. Rev. Retail Distr. Consum. Res., 6(1): 1-33. Monroe, K.B. and S.M. Petroshius, 1981. Buyers Perceptions of Price: An Update of the Evidence. Perspectives in Consumer Behavior, Glenview, Foresman and Company, IL: Scott, pp: 43-55. Morgan, R.M. and S.D. Hunt, 1994. The commitmenttrust theory of relationship marketing. J. Market., 58: 20-38. Narayandas, D., 1998. Measuring and managing the benefits of customer retention an empirical investigation. J. Serv. Res., 1(2): 108-128. Nelson, M. and L., McLeod 2005. Adolescent brand consciousness and product placements: awareness, liking and perceived effects on self and others. Int. J. consum. Stud., 29(6): 515-528 Oliver, R.L., 1993. Cognitive, affective, and attribute bases of the satisfaction response. J. Consum. Res., 20(3): 418-430. Olsen, S.O., 2007. Repurchase loyalty: The role of involvement and satisfaction. Psychol. Market., 24(4): 315-341. Rothenberger, S. 2005. Antezendezien und Konsequenzen der Preiszufriedenheit. Wiesbaden, Gabler. Rauyruen, P. and K.E. Miller, 2007. Relationship quality as a predictor of B2B customer loyalty. J. Bus. Res., 60(1): 21-31. Reichheld, F.F., R.G.J. Markey and C. Hopton, 2000. The loyalty effect-the relationship between loyalty and profits. Eur. Bus. J., 12(3): 134-13. Sinha, I. and R. Batra, 1999. The effect of consumer price consciousness on private label purchase. Int. J. Res. Market., 16: 237-251. Slama, M.E. and A. Tashlian, 1985. Selected socioeconomic and demographic characteristics associated with purchasing involvement. J. Market., 49: 72-82. Simon, H., 2004. Preismanagement-Analyse, Strategie, Umsetzung. Wiesbaden, Gabler. Sternquist, B., B. Sang-Eun and B. Jin, 2004. The dimensionality of price perceptions: a cross-cultural comparison of asian consumers. Int. Rev. Retail Distr. Consum. Res., 14: 83-100. 1412 Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol., 4(10): 1403-1413, 2012 Swaminathan, S. and K. Bawa, 2005. Category-specific coupon proneness: The impact of individual characteristics and category-specific variables., J. Retail., 81(3): 205-214. Tellis, G.J. and G.J. Gaeth, 1990. Best value, priceseeking and price aversion: The impact of information and learning on consumer choices. J. Market., 54: 34-45. Urbany, J., E. Dickson, R. Peter and R. Kalapurakal, 1996. Price search in the retail grocery market. J. Market., 60: 91-104. Walsh, G.M., Vincent-Wayne and T., Hennig-Thurau, 2001. German consumer decision-making styles, J. Consum. Affair., 35(1): 73-95. Zeithaml, V.A., 1988. Consumer perceptions of price, quality and value: A means end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Market., 52: 2-22. 1413