forthe in Forest Management presented on Charles Wilbur Miller M. S.

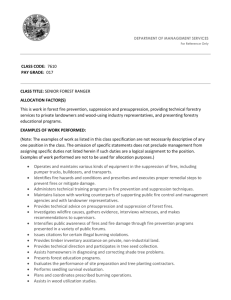

advertisement