Document 13274229

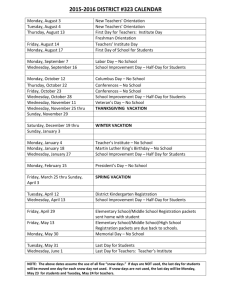

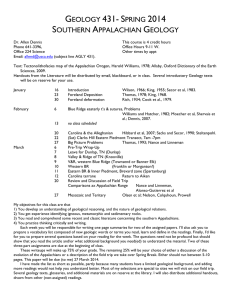

advertisement