POULTRY MANAGEMENT'

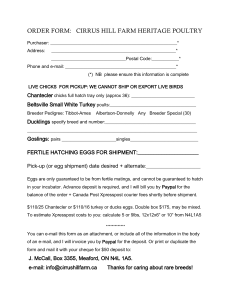

advertisement