POULTRY MANAGEMENT ON THE FARM

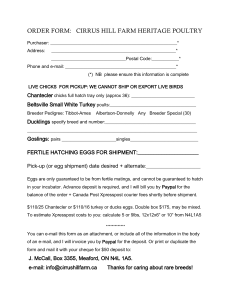

advertisement