K S A C

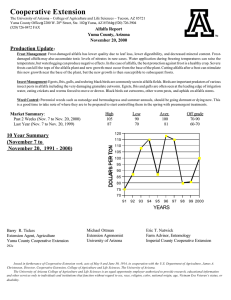

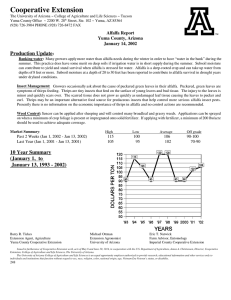

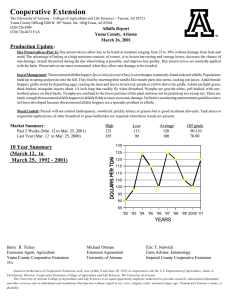

advertisement