AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT COOPERATION APPLIED TO MARKETING BY

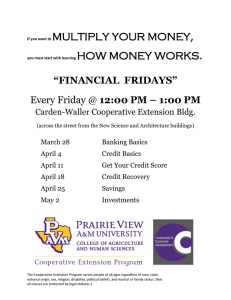

advertisement